Primary tumor (T)

TNM categories

FIGOa stages

Surgical–pathological findings

TX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

Tisb

Carcinoma in situ (preinvasive carcinoma)

T1

I

Tumor confined to the corpus uteri

T1a

Ia

Tumor limited to the endometrium or invades less than one-half of the myometrium

T2

II

Tumor invades stromal connective tissue of the cervix but does not extend beyond the uterusc

T3a

IIIIA

Tumor involves the serosa and/or adnexa (direct extension or metastasis)d

TBb

IIIB

Vaginal involvement (direct extension or metastasis) or parametrial involvement

IIIC

Metastases to pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodesd

IV

Tumor invades the bladder and/or bowel mucosa and/or distant metastases

T4

IVA

Tumor invades the bladder mucosa and/or bowel (bullous edema is not sufficient to classify a tumor as T4)

Regional lymph nodes (N) | ||

|---|---|---|

TNM | FIGO | Surgical–pathological findings |

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |

N1 | IIIC1 | Regional lymph node metastasis to pelvic lymph nodes (positive pelvic nodes) |

N2 | IIIC2 | Regional lymph node metastasis to para-aortic lymph nodes, with or without positive pelvic nodes |

Distant metastasis (M) | ||

|---|---|---|

TNM categories | FIGO stage | Surgical–pathological findings |

M0 | No distant metastasis | |

M1 | IVB | Distant metastasis (includes metastasis to the inguinal lymph nodes, intraperitoneal disease, or lung, liver, or bone). It excludes metastasis to the para-aortic lymph nodes, vagina, pelvic serosa, or adnexa |

In the past 30 years, the role of chemotherapy has emerged, and various chemotherapeutic regimes have been tried and tested as the adjuvant treatment in primary setting.

Diagnosis and Staging Studies

The diagnosis of endometrial cancer is confirmed by the histopathology of endometrial curettage/endometrial biopsy. Thorough evaluation of patient, including complete physical examination, and metastatic workup can define the extrauterine spread of the disease within the pelvis or outside the pelvis, in the abdomen, and in supraclavicular or inguinal nodal areas. These patients often have comorbid conditions of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension which require to be evaluated prior to the treatment decision of the disease.

The workup includes imaging ultrasonography (USG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CA125, and PET–CT when indicated. The ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging appear to be able to diagnose the myometrial invasion and lymph node metastasis with accuracy of 75–95 % [4–7]. The only way of accurately diagnosing the depth of myometrium invasion is by histological examination of the hysterectomy specimen.

Serum levels of CA125 are elevated in most of the patients with advanced or metastatic endometrial cancer [8]. Multivariate analysis showed lymph node metastasis had the most significant effect on elevation of CA125 levels (>40 u/ml), the sensitivity and specificity for screening lymph node metastasis being 78 % and 84 %, respectively. Thus, preoperative CA125 levels greater than 40 u/ml can be considered as an indication for full surgical staging with pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer [9] and may be helpful in monitoring clinical response [10, 11].

Predicting Factors for Advance Stage

The two large prospective surgical staging GOG trials reported in 1984 and 1987 [12, 13] were the landmark trials in defining the prognostic factors of endometrial carcinoma and the current treatment approach for the patients of endometrial cancer.

In addition to intrauterine risk factors of histological type, grade, myometrial invasion, isthmus–cervix extension, and vascular space invasion, the extrauterine factors of adnexal metastasis, intraperitoneal spread, pelvic node metastasis, and para-aortic node metastasis are important in defining the adjuvant treatment. Predicting factors help in selecting the patients who are likely to have advanced disease at presentation and should undergo the extensive surgical staging. The high-risk factors usually modify the survival by either lymph node metastasis or extrauterine spread of the disease.

The following factors can predict the advanced stage of the disease:

- 1.

FIGO stage is the strongest single predictor of outcome in women with endometrial carcinoma as shown in multivariate analysis [14]. The probability of pelvic and para-aortic lymph node involvement and subsequent survival can be determined by the uterine risk factors as well as the extrauterine risk factors.

- 2.

Histologic cell types

The cell type has consistently been recognized as an important factor in predicting the biological behavior of the disease and thus survival. The majority of the uterine corpus tumors are endometrioid adenocarcinoma and usually have relatively good prognosis. Adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation and villoglandular carcinoma behave similarly with respect to the frequency of nodal metastasis and survival to that in endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Serous carcinoma often has low survival rates from 40 to 60 % at 5 years [15–22]; clear cell carcinoma also has very aggressive behavior with a reported 5-year survival rate of 30–75 % [23–30] as the disease is often advanced at presentation.

- 3.

Grade

The degree of histological differentiation is considered to be the most sensitive indicators of tumor spread to either lymph nodes or extrauterine sites. High-grade tumors will have deeper myometrial invasion and increased incidence of pelvic and para-aortic nodal metastasis (Table 8.2). More than half of grade 3 lesions are reported to have >50 % myometrial invasion, 30 % involvement of pelvic, and 20 % involvement of the para-aortic lymph nodes. Survival has also been consistently related to histological grade [13].

- 4.

Myometrial invasion

Table 8.2

Histological grade and depth of invasion grade and no. of patients

Depth | Grade 1 (%) | Grade 2 (%) | Grade 3 (%) | Total (% of total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Endometrium only | 44 (24) | 31 (11) | 11 (7) | 86 (14) |

Superficial | 96 (53) | 131 (45) | 54 (35) | 281 (45) |

Middle | 22 (12) | 69 (24) | 24 (16) | 115 (19) |

Deep | 18 (10) | 57 (20) | 64 (42) | 139 (22) |

Total | 180 (100) | 288 (100) | 153 (100) | 621 (100) |

The depth of myometrial invasion is one of the most important factors, and deep myometrial invasion has high probability of extrauterine disease spread including lymph node metastasis and treatment failure [12, 31, 32].

- 5.

Isthmus–cervix extension

Site of the tumor within the uterus is important in predicting the nodal metastasis. Fundal lesions have 8 % pelvic nodal metastasis and 4 % para-aortic nodal metastasis. In addition, lower uterine segment lesions will have 16 % risk of positive pelvic node and 14 % risk of positive para-aortic nodes [13].

- 6.

Lymphovascular invasion

The lymphatic invasion helps to identify the patients with lymph nodal metastasis and is a strong predictor of tumor recurrence. Vascular space invasion is reported in 15 % of uterus-confined adenocarcinoma [13] with pelvic node positivity in 27 % and para-aortic nodal positivity in 19 %, which is 4–6 times higher in comparison to lymphovascular space-negative patients.

- 7.

Adnexal involvement

The clinical stage I and occult stage II patients have tumor spread to adnexa in 6 % [13] where pelvic and para-aortic nodal metastasis is reported in 32 % and 20 % cases, respectively, which is four times greater than in patients without adnexal metastasis.

- 8.

Intraperitoneal spread

Gross intraperitoneal spread of the disease in absence of adnexal involvement correlates well with higher incidence of involvement of pelvic and para-aortic nodes in about 50 % of patients and 23 % patients, respectively [13, 33, 34]. The pelvic and para-aortic nodal positivity in absence of peritoneal spread is 7 and 4 % only.

- 9.

Pelvic and para-aortic lymph node metastasis

The frequency of pelvic and para-aortic nodal metastasis has been correlated well to various pathological risk factors as shown in Table 8.3. Para-aortic nodal metastasis was in 35 % of the cases where pelvic nodes were positive.

- 10.

Ploidy and steroid receptors

Table 8.3

Frequency of nodal metastasis among risk factors

Risk factors | No. of patients | Pelvic no. (%) | Aortic no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Histology | |||

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 599 | 56 (9) | 30 (5) |

Others | 22 | 2 (9) | 4 (8) |

Grade | |||

1 well | 180 | 5 (3) | 3 (2) |

1 moderate | 288 | 25 (9) | 14 (5) |

3 poor | 153 | 28 (18) | 17 (11) |

Myometrial invasion | |||

Endometrial | 87 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

Superficial | 279 | 15 (5) | 8 (3) |

Middle | 116 | 7 (6) | 1 (1) |

Deep | 139 | 35 (25) | 24 (17) |

Site of tumor | |||

Fundus | 524 | 42 (8) | 20 (4) |

Isthmus–cervix | 97 | 16 (16) | 14 (14) |

Capillary-like space involvement | |||

Negative | 528 | 37 (7) | 19 (9) |

Positive | 93 | 21 (27) | 15 (19) |

Other extrauterine metastases | |||

Negative | 586 | 40 (7) | 26 (4) |

Positive | 35 | 18 (51) | 8 (23) |

Peritoneal cytology | |||

Negative | 537 | 38 (7) | 20 (4) |

Positive | 75 | 19 (25) | 14 (19) |

Ploidy has remained the strong predictor of disease outcome. Diploid tumors show higher survival rates than aneuploid tumors [35]. Positivity and quantity of estrogen receptors and progesterone receptors have been correlated well with clinical stage, histological grade, absence of vascular invasion, and better outcome [36].

Treatment of Advanced Stage

Advanced stage endometrial cancer patients have stage III or stage IV disease. These have increased risk of locoregional as well as distant recurrence and poor prognosis. The use of multimodal approach in the treatment is required which can prevent these recurrences and thus improve survival. These patients may benefit from chemotherapy, tumor-directed radiation therapy, hormonal therapy, or combined treatment. Chemotherapy is regarded as the foundation of adjuvant treatment in advanced stage endometrial cancer.

Treatment of Stage III

Majority of the patients presenting with early-stage disease have good prognosis and survival [37]. Approximately 5–10 % of patients of endometrial cancer present in clinical stage III disease [38]. The patients in stage III include the heterogeneous group of patients of extrauterine disease involving the adnexa, serosa, vagina, or retroperitoneal pelvic or para-aortic nodes with varying risks.

Surgery

Patients presumed to be in advance stage are shown in Table 8.4. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment [38] and requires the following surgical procedures:

Type I hysterectomy

Type II hysterectomy when the cervix is involved by the disease

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

Peritoneal washings for cytological study

Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy

Resection of grossly enlarged nodes when present (Figs. 8.1 and 8.2)

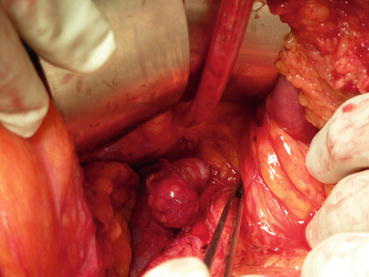

Fig. 8.1

Bulky para-aortic nodal disease in endometrial cancer stage IIIC2

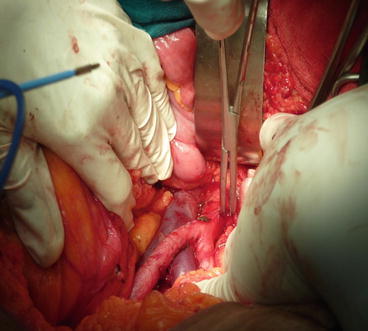

Fig. 8.2

Status post nodal mass excision in endometrial cancer stage IIIC2

Omental biopsy

Omentectomy when histology is serous, clear cell, or poorly differentiated carcinoma

Biopsy of any suspicious peritoneal nodule/lesion

Table 8.4

Risk factors in endometrial cancer

Uterine factors | Extrauterine factors |

|---|---|

Histological type | Adnexal metastasis |

Grade | Intraperitoneal spread |

Myometrial invasion | Positive peritoneal cytology |

Isthmus–cervix extension | Pelvic node metastasis |

Vascular space invasion | Aortic node metastasis |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree