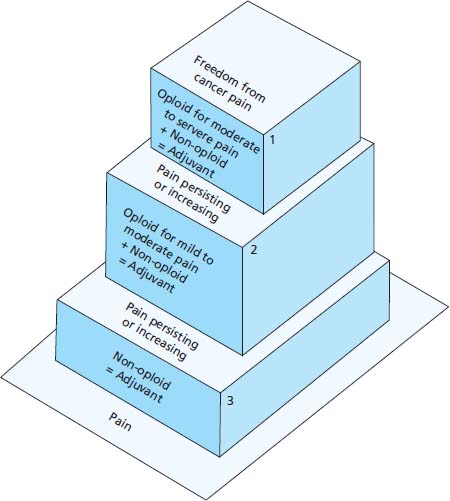

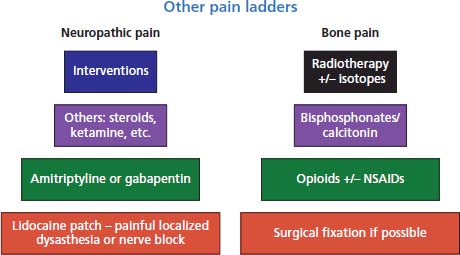

41 Amongst the most important elements of oncological care is recognizing shifting goals as cancer progresses. The balance of benefit and side effects of any intervention should be carefully weighed up. Whilst neurosurgical resection of solitary metastases from melanoma may be appropriate in some circumstances, venipuncture for measuring the serum electrolytes in a dying patient is rarely justifiable. These decisions should involve the patients wherever possible and require skilful use of communication. Throughout the cancer journey patients often enquire about their life expectancy and there is a temptation for clinicians to pluck some figure out of the air. An intelligent doctor will recognize the pitfalls of prognostication when applied to an individual and will appreciate that the median survival (the statistic most relevant in this circumstance) is the time when half the patients will still be alive. Stephen J. Gould, the evolutionary palaeontologist, explained this from a patient’s perspective in the essay “The median is not the message” published in the collection Bully for Brontosaurus and also published in full online. During the patient’s journey with cancer a number of emotions are experienced and these may follow a stepwise succession originally described by the Swiss psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. In her 1969 book, On Death and Dying, she records the stages as denial, anger, bargaining, grieving and finally acceptance. As the cancer progresses and the patient deteriorates, it is important that reviews are frequent and that problems are anticipated. This close follow-up is often best undertaken in the community by community palliative care services rather than bringing patients up to hospital or GP surgeries for regular appointments, but this approach requires excellent communication between all the health professionals involved. This may be facilitated by patient-held records similar to those used in shared care obstetrics. The anticipation of symptoms, including pain and diminishing mobility, should be addressed in advance so that analgesia is quickly available to patients. Nerve endings, or nociceptors, exist in all tissues and are stimulated by noxious agents including chemical, mechanical and thermal stimuli, giving rise to pain (Table 41.1). These stimuli are relayed by Aβ, Aδ (fast transmitting fibres) and C (slow transmission of sensation) sensory nerve fibres to the dorsal horns of the spinal cord and different qualities of pain may use different sensory fibres. Analgesic drugs form the mainstay of treating cancer pain and should be chosen based on the severity of the pain rather than the stage of the cancer. Drugs should be administered regularly to prevent pain using a stepwise escalation from non-opioid, to weak opioid and then strong opioid analgesia (Figure 41.1). Adjuvant drugs may be added at any stage of the analgesic ladder as they may have additional analgesic effect in some painful conditions (Figure 41.2). Examples of adjuvant analgesics are corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants and some antiarrhythmic drugs. Morphine is the most commonly used strong opioid analgesic and whenever possible should be given by mouth. The dose of morphine needs to be tailored to each patient and be repeated at regular intervals so that the pain does not return between doses. There is no upper dose limit for morphine; however, a number of myths have arisen around opioid prescribing that may deter prescribers as well as patients. Firstly, opioid tolerance is rarely seen in patients with cancer pain and neither psychological dependence nor addiction is a problem in this patient group. The toxicity of opioids may prove to be an obstacle for some patients (Table 41.2). Sedation is common at the start of opioid therapy but resolves in most patients within a few days. Similarly, nausea and vomiting may prove troublesome at the start of regular opioid dosing but usually dissipate within a few days and may be controlled with antiemetics. Constipation develops in almost all patients on opioids and this toxicity persists and necessitates routine prophylactic laxatives for almost everyone receiving opioids. A careful explanation of these issues will result in the acceptance of opioid analgesia by almost all patients. Figure 41.1 The World Health Organization’s three step ladder to the use of analgesic drugs. Figure 41.2 The neuropathic and bone pain ladders. Table 41.1 Definition of pain terms Table 41.2 Side effects of opiates The continuing attention to the needs and comfort of a dying patient is as important as the care given to any other patient and part of that care includes reducing the distress of relatives. Many issues may be raised by relatives that pose ethical dilemmas and these may make you question the therapy that has been or should be given. Amongst the most frequent scenarios is the role of intravenous hydration, evaluating the balance between painful cannulation and restriction of mobility versus an uncomfortable dry mouth and thirst. To address these questions you should consider whether death from the cancer is now inevitable, whether interventions would relieve symptoms and whether treatment would cause harm. Careful explanation to the relatives is essential; in this circumstance, for example, they need to be reassured that the patient is not dying because of dehydration but rather because of progression of the cancer. Symptom control in the dying patient often requires a different route of administration as swallowing may be difficult and agitation and restlessness are often prominent features as death approaches. A number of factors may contribute to terminal agitation including physical causes such as pain, sore mouth and full bladder or rectum, along with emotional factors including fear of dying and the distress of relatives. The physical causes should be addressed appropriately and unnecessary medications should be stopped. Often the best method of delivering analgesia, antiemetics and sedation, if appropriate, is via a subcutaneous syringe driver. Similarly, oral secretions accumulating in a patient who is too weak to cough may be distressing to the patient and family alike. Drug treatment for terminal secretions includes hyoscine hydrobromide and glycopyrronium bromide, which is less sedating. It is important to recall that not all patients wish to be sedated and this should be discussed with them and their families. For many patients with cancer the last hours and days are heralded by a deterioration to semiconsciousness. At this time patients are usually unable to take oral medication and prescriptions need to be reconsidered. Many medicines may be stopped altogether and alternative routes of administration, including subcutaneous, rectal and transdermal routes, may be employed for other necessary medications including analgesia. Although patients may no longer be receiving medicines by mouth, oral hygiene remains an important part of overall care. It is particularly important to avoid unnecessary unpleasant interventions at this time and to adopt a practical problem-oriented approach to symptom control. A practical guide to the care of the dying patient in a hospital was developed at the Royal Liverpool Hospital in conjunction with Marie Curie Cancer Care to transfer best practice learnt from hospice care. The Liverpool Care of the Dying Pathway (LCP) helps members of the multidisciplinary team in making a decision about which medical interventions should be stopped and which one should be continued (including anticipatory prescribing) and what comfort measures should be started. It also promotes psychological support of the patients, family and carers as well as addressing spiritual needs and bereavement. There has been debate recently about the value of the Liverpool Pathway, with some critics suggesting that it is a one-way road that sanitizes and precipitates the process of dying without allowing thought or revision of decisions. In 2012, half of all NHS trust were to receive financial rewards under the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) scheme for hitting targets associated with this pathway. This perhaps inevitably led to a furore about the pathway with media critics accusing clinicians of hastening death with a “sedation and dehydration” tactic. In July 2013 the Department of Health decided to phase out the LCP in favour of more individualized end-of- life care. When death is inevitable, as it is for all of us, and is approaching rapidly it is the policy in many UK hospitals to discuss resuscitation policies with patients and their relatives. Under these circumstances resuscitation is rarely appropriate and, if deemed futile, the lead clinician may make a “do not attempt resuscitation” (DNAR) decision. These DNAR decisions should be discussed with patients who wish to engage in advanced care planning. However, prolonged discussions about DNAR policies with patients who do not wish to contemplate their future are, in the view of these authors, distressing and irrelevant. The reason for our autocratic view is that cardiac resuscitation cannot return the patient who has died from cancer from his journey across the River Styx, and it causes distress in the relatives and the arrest team. Bereavement care and support includes recognizing the physical and emotional needs of families and carers and continues after the patient’s death. A number of features have been identified that are associated with the risk of severe bereavement reactions (Table 41.3), and the recognition of these risks prior to death can allow planning of care for those left behind after the death. Health professionals are not immune to bereavement, or at least the good ones are not, and our need for support should not be ignored. Table 41.3 Risk factors for bereavement Just as different cultures, regardless of the scientific evidence, have developed distinct explanations for the origins of life ranging from Big Bangs and evolution to creationist genesis, similar cultural variations affect attitudes to death. For example, Christians, Jews (Box 41.1) and Sufis believe in resurrection whilst Hindus, Buddhists (Box 41.2) and Sikhs believe in reincarnation. These cultural discrepancies must be recognized and respected, particularly where patients’ and carers’ views differ.

End-of-life care

Pain control

Term

Definition

Allodynia

Pain due to a stimulus that does not normally cause pain

Analgesia

Absence of pain in response to stimulation that would normally be painful

Dysesthesia

An unpleasant abnormal sensation, whether spontaneous or evoked

Hyperalgesia

Heightened response to a normally painful stimulus

Hyperpathia

An abnormally painful reaction to a stimulus, especially a repetitive stimulus, as well as an increased threshold

Hypoalgesia

Diminished pain in response to a normally painful stimulus

Neuralgia

Pain in the distribution of a nerve or nerves

Neuropathic pain

Pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the peripheral nervous system

Nociception

Nervous system activity resulting from potential or actual tissue-damaging stimuli

Paraesthesia

An abnormal sensation, whether spontaneous or evoked

Side effect

Comments

Constipation

This affects almost all patients and also all patients require prophylaxis with a stimulant laxative (e.g. senna, bisacodyl) and a softener (e.g. docusate sodium) or as a combined preparation (e.g. co-danthramer, co-danthrusate)

Drowsiness

Generally remits after a few days

Nausea

Affects one-third of opioid naïve patients but usually resolves within 1 week. Consider prophylaxis for 1 week.

Hallucinations

An uncommon side effect that often features images in the peripheral vision

Nightmares

Vivid and unpleasant but rare

Myoclonic jerks

Occur usually with excess doses and may be mistaken for fits

Respiratory depression

Not a problem in patients with pain

Care of the dying patient

The last hours and days

Bereavement

Patient

Young

Cancer

Short illness, disfiguring

Death

Sudden, traumatic (haemorrhage)

Relationship to patient

Dependent or hostile

Main carer

Young, other dependents, physical or mental illness, unsupported

The culture of death and dying

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree