I. GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Clinical psychiatric disorders occur in up to half of patients with cancer at some point during their treatment. Delirium, depression, and anxiety are most frequently seen and may coexist in the same patient Vigilant monitoring for early symptoms of psychiatric distress is important in the care of these patients. The clinician should inquire regularly about symptoms in affective and cognitive domains. Symptom clusters help differentiate anxiety, depression, and acute confusional states from other psychiatric disorders. Once an accurate diagnosis is made, safety, tolerability, efficacy, and price influence choice of medication. More than one psychiatric diagnosis may be present, requiring a hierarchical approach. For example, if both delirium and depression are present, the cause of the delirium should be determined and treated before starting antidepressant therapy (which could worsen the delirium). Once the delirium has improved, treatment for the depression can be considered. When major depression and an anxiety disorder coexist, treatment for the depression is started first and may adequately manage both disorders.

II. ACUTE CONFUSIONAL STATES

Approximately 15% of hospitalized patients with cancer experience delirium, but this can increase to 80% to 85% in those receiving palliative care.

A. Precepts

Attempting to treat delirium with psychotropic drugs, but without understanding the cause of the patient’s confusion, can have serious consequences. Delirium is characterized by fluctuating levels of alertness and consciousness, shortened attention and concentration, rapidly changing moods, irregular sleep-wake cycles, garbled or slurred speech, hypervigilance, and behavior not consistent with good judgment. The delirious patient may also have delusional ideas or hallucinations or appear depressed. Visual, auditory, tactile, and occasionally olfactory hallucinations can be present. The more sensory modalities that are involved in the hallucinations, the greater the likelihood that the patient is experiencing a medically induced confusional state.

B. Etiologies

1. Medications remain the most common reason for acute confusional states. The most frequently identified medications to cause delirium are sedatives, narcotic analgesics, anxiolytics, anticholinergic drugs, and corticosteroids. Antineoplastic and immunotherapeutic agents can cause delirium: cytarabine, methotrexate, asparaginase, fluorouracil, interferon, and interleukin. Even histamine blockage from agents like diphenhydramine or famotidine can lead to delirium.

2. Metabolic causes are often seen in patients with cancer and include hypernatremia and hyponatremia, hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, vitamin deficiencies (B12, folate, thiamine), and hypercalcemia.

3. Infections of the respiratory, urinary, central nervous, and other systems are common, especially in immunosuppressed patients.

4. Chemical withdrawal from benzodiazepines, alcohol, and other drugs can induce delirium.

5. Medical illness such as tumors, particularly primary brain tumors and brain metastases, cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, liver disease, trauma, strokes, and renal failure. Hyperviscosity syndrome with lymphoma, myeloma, and Waldenström macroglobulinemia are unusual causes. After radiation to the brain, confusional states can occur, especially if the patient received a small amount of steroid. An acute confusional state can occur secondary to a paraneoplastic syndrome frequently associated with lymphoma. In addition to the original illness, postoperative head and neck surgery, often for malignancy, carries a higher risk than many other surgical procedures for delirium.

C. Therapeutic approach

Once an acute confusional state is identified, the primary therapeutic approach is to treat the cause. The key is to determine when symptoms of delirium first occurred and to look for preceding changes in medications, vital signs, laboratory studies, or imagery/radiology. This helps to determine how to best proceed with treatment (e.g., withdrawing a medication or treating a urinary tract infection found on a urinalysis). When hypoactive delirium occurs, inclining the head to 30% reduces the risk for aspiration. Moving the patient frequently may prevent bed sores. Hyperactive patients with delirium are at high risk for falls and subsequent fractures. Research has demonstrated that a combined protocol of physical mobilization, cognitive exercise through conversation and reorientation, appropriate hydration, use of glasses or hearing aids from home, and minimizing sedatives at night can reduce the number, severity, and cost of delirium episodes. Antipsychotic medications may be helpful for managing symptoms such as hallucinations,

delusions, and extreme agitation, but they do not treat the cause of the delirium.

1. Orientation (frequent reconnection) of the patient aids in reduction of confusion.

a. It is helpful to orient the patient frequently to place, time, and why they are at the hospital and to give current explanations of procedures. This routine should be done once or more per shift when the delirious patient is awake. Because the patient’s attention, concentration, and recent memory are frequently impaired, the patient often does not recall instructions given earlier. Leaving a large, legibly written note card with the patient’s name, date, hospital name, and other data is beneficial in some instances.

b. A large calendar, a clock, and family pictures or mementos can assist the patient in feeling less estranged from his or her environment. It can be very reassuring to a patient if a family member can stay with them overnight.

c. Some patients are reassured by a small night light in their room, which cuts down on illusions or misinterpretations. Patients with compromised vision or hearing are particularly distraught when they are even less able to discern what is happening around them, and they should be provided with their regular hearing aids and glasses.

2. Medication helps to control hallucinations, delusions, and psychotic agitation. The lowest dose to control symptoms is usually preferable.

a. Haloperidol (Haldol; Table 32.1) is a butyrophenone, an antipsychotic agent with potent dopamine-blocking action. It is less likely to produce cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and general anticholinergic side effects than many of the other antipsychotic medications. However, moderate doses may cause extrapyramidal symptoms. The starting dose in a patient with an acute confusional state is 0.25 to 2 mg by mouth or intramuscularly, on an as-needed or regular dosing schedule every 4 to 6 hours. A marked advantage of haloperidol is that sedation is minimized while controlling agitation. There are exceptions to the usually preferred low doses of antipsychotic medications. For example, if patients tolerate higher doses with few side effects, they may benefit by having improved pain control. Intravenous (IV) haloperidol has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, although it is commonly used in the seriously agitated patient. There are fewer extrapyramidal symptoms with IV haloperidol, but the half-life in this form is much shorter, requiring more frequent administration. Avoid very high doses in patients

with alcoholic cardiomyopathy, those prone to torsades de pointes or similar arrhythmias, and those with an excessively long corrected QT interval.

TABLE 32.1 Antipsychotic Medications: Prominent Characteristics and Dosage For Patients With Cancer

Agent

Starting Dose (mg)*

Characteristics

Phenothiazines

Chlorpromazine (Thorazine)

10-25

Significant hypotension risk, lowers seizure threshold, highly sedating, anticholinergic

Thioridazine (Mellaril)

10-25

Similar to chlorpromazine but more likely to alter electrocardiogram, not available IM

Perphenazine (Trilafon)

4

Moderate sedation and hypotension

Trifluoperazine (Stelazine)

2

High frequency of extrapyramidal side effects

Others

Haloperidol (Haldol)

0.5-2.0

Good for acute delirium, high frequency of extrapyramidal side effects, available IV, IM, or PO; short-acting; IV haloperidol has a very short half-life and must be given frequently, but there is much less extrapyramidal side-effect; IM depot every 2-4 weeks

Risperidone (Risperdal)

0.5-1.0

Some α-adrenergic effects, mild extrapyramidal side effects as dose increases, PO form for daily use; IM depot (2 week) form

Olanzapine (Zyprexa)

5

More sedation; weight gain; fewer extrapyramidal side effects; PO form regular capsule, liquid, and tablet that dissolves on tongue; IM for acute use up to two times per day

Quetiapine (Seroquel)

25-50

More sedation, fewer extrapyramidal effects

Ziprasidone (Geodon)

20

Less weight gain, fewer extrapyramidal effects, IM for acute use up to two times per day

Aripiprazole (Abilify)

5-20

Less weight gain and extrapyramidal effects, can elevate mood, occasionally to hypomania

Asenapine (Saphris)

5

Sublingual tablets, avoid eating or drinking for 10 minutes after administration

IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PO, by mouth.

* Dose generally can be repeated every 4-6 hours (other than risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, asenapine), on either an as needed or a regular schedule (e.g., twice a day).

b. Risperidone, olanzapine, ziprasidone, quetiapine, and aripiprazole. Risperidone (Risperdal, Risperdal M-Tab) is less likely to produce extrapyramidal side effects, but is available only in oral form for acute (nondepot) use. Olanzapine (Zyprexa, Zydis) is sedating and can be given in a tablet that dissolves on the tongue or in an intramuscular form. Ziprasidone (Geodon)

can also be given in a rapid onset intramuscular preparation. Quetiapine (Seroquel) is only available orally, as is aripiprazole (Abilify, Abilify Discmelt). Aripiprazole acts slowly and would not help reduce symptoms quickly. Some immediate antipsychotic preparations can be crushed and put in a feeding tube.

c. A delirious patient with vision or hearing impairment is likely to hallucinate during periods of excessive sedation, especially if there is pulmonary compromise or a tendency toward hypoxia.

d. If the patient demonstrates a predictable period of confusion, such as during the early evening (“sun-downing”) when there is less environmental activity, a small once-a-day dose at that time may be adequate.

e. When increasing the dose of antipsychotic drugs, muscle spasms, restlessness, or pseudoparkinsonian symptoms may occur with older first-generation antipsychotics and some second-generation agents like risperidone or ziprasidone. Adding a small amount of trihexyphenidyl (Artane) 1 to 2 mg twice a day, benztropine (Cogentin) 1 mg twice a day, or diphenhydramine (Benadryl) 25 mg twice a day can often reduce the side effects. However, increasing the level of anticholinergic activity with these choices may cause an atropenic-like psychosis. Constipation, urinary retention, dry mouth, tachycardia, and increasing confusion are warnings of this potential problem, especially when multiple anticholinergic medications (e.g., antiemetics, analgesics) are being prescribed. Therefore, antiparkinsonian drugs are not prescribed prophylactically but only if clearly indicated. Ondansetron (Zofran), granisetron (Kytril), or dolasetron (Anzemet) may be substituted for other antiemetics, reducing extrapyramidal symptoms and avoiding the need for an antiparkinsonian medication. Some antiemetics (e.g., droperidol) are also antipsychotics, but these, like metoclopramide, can lead to extrapyramidal symptoms like akathisia or dystonias.

f. Benzodiazepines such as lorazepam (Ativan) can be given 0.5 to 2.0 mg every 8 hours. They can be administered in small doses to a patient who needs some sedation without added anticholinergic activity or those whose cardiac status is at risk (i.e., heart block) if some antipsychotic medications were increased. Using both benzodiazepines and antipsychotics is sometimes helpful.

g. Increasing delirium. Too much medication may have been given if the patient’s agitation increases with higher doses. Secondary hypoxia and akathisia should be excluded. High blood levels of longer-acting medications can accumulate,

particularly if serum albumin and protein is low and hepatic and renal functioning are compromised.

h. Hypotension. Avoid adding a second antipsychotic (e.g., chlorpromazine), as it may predispose to hypotension and shock. If the blood pressure does drop significantly, norepinephrine bitartrate (Levophed) or a similar choice may be necessary as antipsychotic medications like haloperidol also block some peripheral actions of dopamine.

III. DEPRESSION

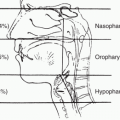

Depression is roughly four times more common in patients with cancer than in age-matched controls. Oropharyngeal, pancreatic, lung, and breast cancer are associated with the highest rates of depression. Earlier studies indicated that patients with both cancer and depression had a higher risk of death, but larger meta-analysis did not find this to be true. However, patients who are depressed report poorer pain control, poorer compliance, and more often choose to discontinue treatment.

Patients with cancer have various emotional responses to their diagnoses. The mourning period for some is brief, does not inhibit their ability to interact with family and friends, and does not hinder participation in their own treatment. Support from others, acceptance of their feelings, and time may be all that is necessary for them to continue the emotional work ahead. However, about one-fourth of patients with cancer develop longer, more severe depression. The greatest risk of depression is at the time of first relapse. There are many variables that influence this process, including emotional conflicts with loved ones, disproportionate guilt, previous losses that were never resolved, long-standing debilitating illness, individual personality characteristics such as dependency, and inadequate support systems. Any of these factors, along with a family history of depression, are warnings for the physician to heed.

Besides emotional response to the stress of having cancer and undergoing treatment, other causes of depression should be considered. Folate or vitamin B12 deficiencies, thyroid or parathyroid disorders, adrenal insufficiency, leptomeningeal disease, and brain metastases can induce depression. Interferon can sometimes precipitate sadness to suicidal proportions in patients who have never previously experienced depression. Some recommend an antidepressant be started 2 weeks prior to starting interferon if a patient has a prior history of major depression.

Passive suicidal thoughts with depression are common. Patients who actually do commit suicide are more likely to be male, have advanced disease, and a history of psychiatric illness, substance abuse, and prior attempts. Good pain control and efforts to reduce isolation can lessen suicidal thoughts and behavior.

A. Therapeutic approach

1. Emotional support at frequent intervals from the physician is generally needed. Some patients explore old emotional conflicts, whereas others just need a safe person to whom they can express their feelings. It is important for patients to be able to hold on to hope. A degree of denial is acceptable, normal, and upheld. Only when this denial makes it impossible for a patient to make informed treatment decisions is it necessary to probe into the denial.

Psychotherapy of a supportive nature is often provided by the primary care physician, oncologist, psychiatrist, clergy, nurse, family, or friend individually or in any combination. For patients who wish to explore ambivalence, a professional psychotherapist trained in psychodynamic or interpersonal therapy is a good option. Cognitive therapy is helpful in letting go of detrimental interpretations while increasing one’s ability to deal with emotional pain.

2. Psychiatric care

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Emotional and Psychiatric Problems in Patients With Cancer

Emotional and Psychiatric Problems in Patients With Cancer

Kristi Skeel Williams

Kathleen S.N. Franco-Bronson