Table 1

Summary of studies examining liver resection versus liver transplant for early hepatocellular cancer

First author (year) | Treatment groups | Total patients | Childs A/B/C or average MELD | Mean maximal tumor size (cm) | 5-year disease free survival (%) | 5-year overall survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Figueras (2000) [35] | Resection | 35 | 31/4/0 | 4.8 | 31 | 51 |

Transplant | 85 | 43/35/7 | 2.8 | 60 | 60 | |

Margarit (2005) [33] | Resection | 37 | 37/0/0 | 3.2 | 39 | 70 |

Transplant | 36 | 36/0/0 | 3.0 | 64 | 65 | |

Poon (2007) [34] | Resection | 204 | 195/9/0 | <5 | 42 | 68 |

Transplant | 43 | 8/15/20 | <5 | 84 | 81 | |

Del Gaudio (2008) [36] | Resection | 80 | 55/14/0 | 3.1 | 41 | 66 |

Transplant | 293 | 23/139/131 | 1.3 | 71 | 73 | |

Bellavance (2008) [38] | Resection | 245 | 9.1 | NR | 40 | 48a |

Transplant | 134 | 11.0 | 82 | 79a | ||

Lee (2010) [111] | Resection | 130 | 113/17/0 | 4.5 | 50 | 52 |

Transplant | 78 | 35/43/0 | 3.8 | 75 | 68 | |

Koniaris (2011) [37] | Resection | 106 | 7.3 | 6.1 | 45 | 53 |

Transplant | 257 | 12.9 | 3.0 | 60 | 62 |

Final consensus on the comparative debate between LR and LT for early stage HCC with compensated liver disease remains lacking. While disease-free survival is clearly better among patients undergoing LT, the relative overall survival benefit of LT over LR remains ill defined. While LT has benefits over LR, it remains unclear whether patients who recur following LR can be salvaged with LT and experience the same long-term survival [39–41]. Prospective, randomized studies taking into account tumor size, multifocality, waitlist time and organ availability, and comorbidities, with appropriate long-term follow-up are needed to better address the LR versus LT debate.

2 Colorectal Liver Metastases

In the United States, colorectal metastases to the liver (CRLM) are probably the most common secondary malignancy involving the liver [42]. Approximately 140,000 Americans are diagnosed with colon cancer annually, with more than half of these patients eventually developing metastases [43]. Most of these metastases are found in the liver, and the presentation may vary from disease that is isolated to the liver and resectable to disease with tumor burden that is extensive and unresectable [44]. Given the heterogeneity of this patient population with metastatic disease, combined with developments in NRLTs and a paucity of prospective data, numerous CER issues have arisen in the surgical oncology literature.

2.1 Role of Loco-regional Therapies in Patients with Unresectable Disease

Unfortunately, most patients with CRLM have unresectable disease [45]. There are numerous reasons why a patient may be unresectable and not be an appropriate candidate for LR, including multiple small tumors, vascular involvement of the tumor, a small future liver remnant (FLR), medical comorbidities, or extra-hepatic disease. Typically patients with unresectable disease are treated with systemic therapy, with an associated median survival of 2 years and 5-year survival around 10–15 % [46, 47]. For those patients with liver predominant or liver only disease that is unresectable, local therapies may have a possible therapeutic role over systemic therapy. These options include RFA, TARE with Yttrium-90 microspheres, TACE with irinotecan eluting beads (DEBIRI), and hepatic artery infusion (HAI) pumps [48, 49].

The role for RFA has been examined frequently as one of the more common alterative or adjunct therapeutic options for patients with unresectable advanced disease [50–55]. Siperstein et al. [56] examined a retrospective cohort of patients with unresectable CRLMs that were treated with RFA. A unique strength to this study was its extensive 10-year follow-up. In the cohort of 234 patients—all of whom were treated with RFA—the 5-year survival was 18.4 %, which the authors noted was better than the 5-year survival or 10 % for historical controls treated with systemic therapy alone [57]. In a separate study, as part of the Intergroup 40,004 trial contrast, Ruers et al. [58] reported their findings for patients with unresectable CRLM. In this prospective study, the investigators compared systemic FOLFOX-based chemotherapy combined with RFA versus systemic therapy alone for patients with advanced CRLM. The authors noted that 30-month overall survival was similar: 61.7 % in the combined arm versus 57.6 % in the systemic therapy alone arm (p = NS). Median overall survival was also similar: 40.5 months in the systemic arm versus 45.3 months in the combined treatment arm (p = NS). While overall survival was the same in both groups, 3-year progression free survival was worse in the systemic alone arm (10.6 % vs. 27.6 %, HR = 0.63, p = 0.025). Therefore, the authors concluded that overall survival for patients with unresectable disease treated with systemic therapy alone versus ablation plus systemic therapy was similar, while progression free survival was improved with the use of ablation.

Other local therapies have also shown promise, however the data supporting their use is not as robust and therefore is a focus on CER. One such therapy is the HAI pump. First proposed in 1984, the role for HAI has been controversial, and its efficacy has been compared to systemic therapies in multiple prospective studies [59–62]. Many of these studies, however, have been criticized due to low sample size, patient cross-over, and the single-center nature of the trials [63]. In an effort to address these issues, Kemeny et al. [63] prospectively compared HAI pump therapy with systemic therapy in a large multi-institutional trial that did not allow cross-over. The authors reported that overall survival was improved for patients who received HAI versus systemic chemotherapy (median, 24.4 months vs. 20 months, p = 0.0034). Additionally, response rates were higher (47 % vs. 24 %, p = 0.012) and time to hepatic progression was longer (9.8 months vs. 7.3 months, p = 0.034) with HAI therapy. While these data were promising, other studies have challenged the survival benefit of HAI. In a meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials performed comparing HAI with systemic chemotherapy, Mocellin et al. recently suggested that there is no evidence supporting the use of HAI. In the pooled analysis, while tumor response rate was expectedly better in the HAI group (42.9 % vs. 18.4 %, RR 2.3, <0.001), overall survival was not different comparing HAI versus systemic therapy (15.9 months vs. 12.4 months, HR 0.9, p = 0.24, respectively). While HAI therapy may provide some benefit in the treatment of advanced colorectal liver metastasis, more CER is needed to determine the role for HAI.

Other newer local therapies such as TACE with irinotecan beads (DEBIRI) and TARE with Yttrium-90 (Y-90) have posed CER issues in the context of unresectable CRLM. There are emerging data for the use of transarterial DEBIRI in the treatment of unresectable liver metastasis [64–66]. Many studies, however, incorporate TACE or TARE only for patients who are refractory to systemic therapies. Martin et al. [66] reported 55 patients who had received prior systemic chemotherapy and who underwent DEBIRI treatment. In this series, response rates were 66 % at 6 months and 75 % at 12 months. TARE with Y-90 has also been investigated for patients refractory to chemotherapy [67, 68]. Cosimelli et al. [68] in a prospective multicenter phase II trial, evaluated the effect of TARE on patients who had failed previous oxaliplatin and ironotecan based chemotherapies. Based on RECIST criteria, 2 % had a complete response, 22 % a partial response, 24 % had stable disease, 44 % had progressive disease, and 8 % were non-evaluable. Because of these promising results, a phase III multicenter clinical trial, Efficacy Evaluation of TheraSphere following Failed First-Line Chemotherapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (EPOCH) trial will soon open to elucidate the effect of TARE on not just response rates, but also overall survival. Final consensus on the optimal management of patients with unresectable CRLM is still developing, but progress is being made with emerging meta-analyses and prospective studies.

2.2 Ablation Versus Liver Resection

For the 10–25 % of patients with resectable CRLM, LR is the standard treatment approach with 5-year survival following surgery now approaching 60 % [42, 69, 70]. The role of ablation versus surgery among patients with CRLM potentially amenable to either therapy has been debated. The median overall survival associated with LR of CRLM reported in the literature ranges from 24 to 59 months whereas the data on survival following ablation are more limited [52, 71]. Several studies have sought to compare outcomes for patients who underwent ablation versus patients who underwent resection for CRLM [72–76]. Abdalla et al. [52] reported on 358 consecutive patients who underwent hepatic resection with or without RFA for CRLM. In this cohort, LR provided a significantly better overall 4-year survival over RFA alone, (65 % vs. 22 %, p < 0.001). Similarly, Hur et al. [77] noted a 5-year survival advantage for patients who underwent LR versus RFA (25.1 % for RFA vs. 50.0 % for LR). Based on the available data, it appears that patients managed with ablation have a worse outcome compared with patients who underwent hepatic resection (Table 2) [72, 74–76, 78].

Table 2

Summary of studies comparing RFA with resection for colorectal liver metastases

First author (Year) | Treatment groups | Total patients | Mean maximal tumor size (cm) | Median time to local recurrence (months) | Median survival (months) | 5-year local recurrence free survival | 5-year overall survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Oshowo (2003) [72] | RFA | 25 | 3 | NR | 37 | NR | 52.6a |

Resection | 20 | 4 | NR | 41 | 55.4a | ||

Aloia (2006) [78] | RFA | 30 | 3.0 | 18 | NR | 60 | 27 |

Resection | 150 | 3.5 | 31 | NR | 92 | 71 | |

White (2007) [74] | RFA | 22 | 2.4 | NR | 31 | NR | 0 |

Resection | 30 | 2.7 | NR | 80 | NR | 58 | |

Berber (2008) [75] | RFA | 68 | 3.7 | NR | 34 | NR | 30.0 |

Resection | 90 | 3.8 | NR | 57 | NR | 40.0 | |

Lee (2008) [76] | RFA | 37 | 2.25 | NR | NR | 42.6 | 48.5 |

Resection | 116 | 3.29 | NR | NR | 84.6 | 65.7 | |

Hur (2009) [77] | RFA | 25 | 2.5 | NR | NR | 69.7 | 25.5 |

Resection | 42 | 2.8 | NR | NR | 89.7 | 50.1 | |

Reuter (2009) [113] | RFA | 66 | 3.2 | 12.2 | 27.0 | NR | NR |

Resection | 126 | 5.3 | 31.1 | 36.4 | NR | NR |

The difference in the outcomes may, however, not be solely attributable to the type of therapy delivered (i.e. LR versus ablation), but also an issue of disparate underlying tumor biology among each patient population. Specifically, patients who undergo ablation as treatment for their CRLM often represent a distinct subgroup of patients with otherwise advanced disease who are not amenable to surgical extirpation [79]. In fact, many of the clinicopathologic features such as tumor size and number are often different in the group of patients receiving LR versus ablation. To achieve more comparable groups, subgroup analyses of patients undergoing either LR or ablation for CRLM have been performed, which have commonly been stratified by tumor number [78]. For example, Aloia et al. [78] examined a cohort of patients all of whom had only a solitary lesion. In this study, 150 patients treated with resection were compared with 30 patients treated with RFA. The authors reported that patients who underwent resection had a significantly better 5-year survival (resection: 71 % vs. RFA: 27 %; p < 0.001). However, patients managed with RFA likely had worse tumor biology as indicated by a higher proportion of patients with concomitant extrahepatic disease. In a separate study, Gleisner et al. [80] sought to examine how discordant clinicopathologic factors might play a crucial role in comparing patients who underwent resection versus ablation. Specifically, Gleisner et al. compared overall survival between patients who underwent resection with survival of patients who underwent RFA using three distinct statistical methods. The authors reported that patients managed with resection alone had an improved long-term overall survival compared with patients treated with resection plus ablation. The authors noted, however, that there were many differences in the clinicopathologic profile of each group. To examine the comparability of the baseline characteristics of the two treatment groups, Gleisner and colleagues utilized propensity score methodology. The authors noted that the aggregate distribution of the clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients undergoing resection alone versus RFA ± resection were markedly different and therefore direct comparisons of these groups may not be appropriate. The work of Gleisner and colleagues serves therefore to highlight the significant shortcomings of using retrospective data to compare outcomes following resection versus ablation in cohorts of patients who are very different and whose choice of treatment was undoubtedly based in part based of very different baseline characteristics.

In 2009, as part of an American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) evidence-based review, Wong et al. [81] attempted to examine all data available at that time on ablation and LR for CRLM. The authors concluded that the available data were insufficient to form the basis of an evidence-based recommendation. Specifically, the authors noted that there was wide variability in 5-year survival (14–55 %) and local tumor recurrence (3.6–60 %) with ablation compared with LR. In turn, the investigators commented that the question of ablation versus LR could only be answered by a prospective, randomized trial. Such a trial, while ideal, would be challenging for a variety of reasons, most significantly, accrual would be required to be multi-institutional, and the ablation procedure itself would need to be standardized [45]. In an attempt to simulate such a trial, Khajanchee et al. [45] used a Markov and Monte Carlo analysis comparing RFA and LR. The authors reported that the model estimated 5-year survival among those patients who underwent LR over RFA alone to be 38.2 % versus 27.2 %, respectively. Five-year disease-free survival was also superior in the LR group (LR: 29.8 % vs. RFA: 15.5 %). While there are no prospective data comparing ablation with LR in the resectable population, from the limited data available, LR should remain the preferred approach with ablation being used as an adjunct second line therapy.

2.3 Systemic Therapy, Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and the Disappearing Liver Metastasis

While local therapies such as ablation and resection are important treatment options for patients with CRLM, systemic chemotherapy plays a critical role in the multi-modal therapy of these patients. Systemic therapy has the potential of treating micrometastatic disease, evaluating tumor response, and downstaging unresectable tumors to resectability. The benefits of chemotherapy come with some possible consequences, including hepatotoxicity such as sinusoidal dilation, steatosis, or steatohepatitis [47, 57, 82, 83].

In an attempt identify which patients may benefit the most from systemic chemotherapy, several predictive models have been designed to identify patients at high risk for recurrence after hepatectomy. Fong et al. [42] were one of the first groups to propose a clinical risk score for predicting recurrence and survival. This study identified several prognostic factors for recurrence including: extra-hepatic disease, node-positive primary tumor, disease free interval from primary to metastases <12 months, CEA level >200, largest hepatic tumor >5 cm, and number of hepatic tumors >1. Similarly, Adam et al. [84] also created a prognostic model, examining initially unresectable CRLM that received chemotherapy and that were downstaged to resectability. In this study, the investigators identified a rectal primary, ≥3 CRLMs, maximum CRLM size of ≥10 cm, and CA19-9 >100 as independent factors of poor prognosis. Capussotti et al. [85] in 2007 suggested their own prognostic model. These authors identified patients with T4 primary colon cancers, metastases with infiltration of neighboring structures, and patients with more than three metastases as being potential indicators of poor prognosis and, in turn, may indicate a potential benefit from systemic chemotherapy. Despite these large retrospective series, there are still no specific consensus guidelines to indicate which patients with resectable CLRM should receive systemic chemotherapy either in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting [86].

Among the cohort of patients treated with neoadjuvant or preoperative systemic chemotherapy, there are several CER issues that remain debatable. Most data would suggest that those patients who have progressive disease on preoperative chemotherapy have a very poor prognosis [84]. Whether these patients should categorically be refused potential surgery even if the disease is technically still resectable remains controversial. Among patients who have a response to neoadjuvant/preoperative chemotherapy, surgery is typically performed with the goal of resecting all sites of disease. Up to 10–25 % of patients with CRLM who are treated with preoperative chemotherapy, however, will have a complete response with radiographic “disappearance” of some or all CRLM lesions in the liver [87, 88]. The so called “disappearing liver metastasis” (DLM) raises a number of CER issues.

From a radiologic perspective, there is no consensus regarding which imaging modality (CT, MRI, FDG-PET, or FDG-PET-CT) is most appropriate to determine whether the DLM is simply “missing” due to low sensitivity of the chosen imaging modality versus whether it has truly “disappeared.” Most medical oncologists and surgeons currently use CT in the treatment of patients with CRLM. The widespread use of dual phase helical CT is based on clinician familiarity and a high degree of reproducibility with excellent sensitivity and specificity up to 90 % when diagnosing CRLM [89, 90]. In the setting of a DLM, when the liver has been exposed to systemic chemotherapy—often many cycles—the background liver can appear darker with less contrast between the liver and any hypovascular metastases [91]. PET-CT has been considered as adjunct to CT alone, however PET-CT has limited sensitivity in its ability to detect lesions <1 cm and chemotherapy decreases hexokinase activity, thereby inhibiting glucose uptake for CRLM [92, 93]. Recently, there has been increasing data to suggest that MRI should be the imaging modality of choice in the setting of DLM. MRI, has increased sensitivity compared with CT, particularly in the setting of chemotherapy induced hepatic parenchymal changes (Fig. 2) [88]. In a recent meta-analysis, van Kessel et al. [94] compared various imaging modalities in the detection of CRLM after preoperative chemotherapy and found that the sensitivity of MRI was 85.7 % versus 69.9 % for CT, 54.5 % for PET, and 51.7 % for PET-CT. As such, MRI seems to be the imaging modality of choice for patients treated with preoperative chemotherapy—especially those with DLM. Future CER to understand better the role of different imaging modalities in treating patients with CRLM will be needed.

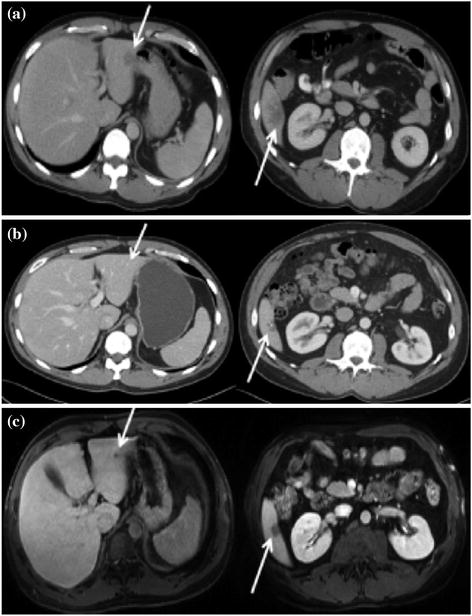

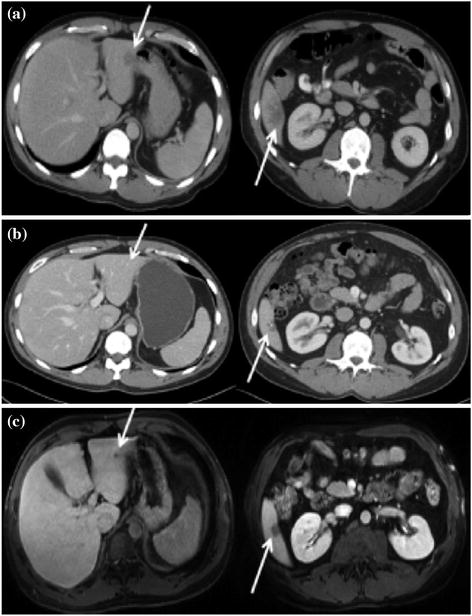

Fig. 2

a Computed tomography (CT) image demonstrating colorectal liver metastases in segments II and VI (arrows) before systemic chemotherapy. b After 6 cycles of FOLFOX (folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) therapy, CT showed that the lesion in segment II had ‘disappeared’, whereas the lesion in segment VI was significantly smaller and calcified. c Magnetic resonance imaging similarly identified the lesion in segment VI, but also demonstrated a residual 7-mm lesion in segment II. Used with permission [88]

In addition to radiological issues in management of DLM, there is also is also a lack of consensus about the surgical management of DLM. As with other CER dilemmas, this primarily stems from the lack of reliable data. van Vledder et al. [87] attempted to examine the question of how to manage DLM using retrospective data; the authors noted that patients with untreated DLM had an increased local recurrence rate compared with patients who underwent LR of the DLM (p = 0.04). Despite these findings, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival was not different for patients undergoing LR versus those patients who had DLM left in situ (92.3 % vs. 93.8 %, 70.8 % vs. 63.5 %, 46.2 % vs. 63.5 % respectively) (Fig. 3a, b). The CER issues raised by the management of DLM were recently addressed by Bischof et al. [88]. In their review of DLM, the authors concluded that among patients who had a complete radiographic response, only 20–50 % had a durable long-term remission. In addition, among patients who had the DLM resected, residual tumor was present in 25–45 % of patients. Therefore, more CER is need to understand which patients need surgery for a DLM after receipt of preoperative chemotherapy.