Adam L. Gordon, Ruth E. Hubbard

Education in Geriatric Medicine

Midway through the second decade of the twenty-first century, geriatric medicine finds itself at an interesting crossroads. There seems to be a “know-do” gap. Although we know about the aging population and how to deliver evidence-based care to achieve the best outcomes, most health and social care economies continue to struggle to do so. Recruitment crises afflict geriatric medicine in North America1,2 and Australia,3 while the availability of geriatricians varies considerably across Europe.4 Outside developed economies, the specialty frequently does not exist.5 Internationally, the specialist nursing skills required to support older people are underrecognized, with implications for recruitment and retention in services for these patients.6 Medical students, although increasingly appreciative of the emotional and intellectual rewards associated with geriatric medicine, continue to recognize financial and status-related limitations associated with a career in the specialty.7

Comprehensive reviews of medical training in the United Kingdom,8 United States,9 and Australia,10 among other countries, have stated that the identification and management of frailty and functional dependency are integral to effective training in general (internal) medicine. However, as countries work out how to operationalize recommendations, a number of tensions have been identified. In some health economies, there are powerful specialties with historical responsibility for generalist practice, examples being general (internal) medicine and general practice. In other countries, emergent specialties have developed to fill the gap left as organ specialists have become ever more removed from general practice by subspecialization such as hospitalism11 in the United States and acute medicine in the United Kingdom.12 At best, these traditional or emerging power-bases have recognized the knowledge and skill sets required to care for older patients, and they are up-skilling appropriately. At worst, they exert control and moral authority over the care of older people with frailty (“We’re all geriatricians now”13) without recognizing the important lessons from the literature around comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) or realizing the skill sets required to deliver it.

A further set of tensions has emerged from the tendency of hospital-based, single-organ or single-system doctors to become ever more subspecialized; this has resulted in two contrary lines of argument. The first states that the needs of those with multiple pathologies would best be met by ensuring that all older patients have access to an appropriate array of subspecialists14; the second states that, in order to maintain a subspecialist skill set, single-organ specialists must retreat from the demands of the acute unselected medical take, as continued involvement will make disproportionate demands on their time with the effective assertion that generalism is the preserve of hospitalists, acute physicians, general practitioners, and geriatricians.15

Clearly these dichotomies will play out differently in different countries, depending on historical power bases, models of health care funding, and prevailing assumptions among doctors, policy makers, and the population at large. However, while the policy and service delivery context differs between nations, the basic fundamentals of what doctors and other health care professionals need to deliver good care remain the same. That is to say, effective education in the core knowledge, skills, attitudes, and competencies in the care of older people is a banner behind which geriatricians around the world can effectively rally to drive up the standards seen by patients.

This chapter presents a summary of recent progress in key areas of education about health care of older people under four main headings: (1) what doctors need to know, (2) innovations in how we teach doctors what they need to know, (3) the importance of multidisciplinarity and interprofessional education, and (4) facilitators and barriers to effective educational interventions.

What Doctors Need to Know About Aging

All doctors need to know something about aging. Older people make up the largest proportion of health and social care users. In the United Kingdom, two thirds of acute hospital admissions are aged older than 6516 and the highest general practice consultation rates are for people aged 85 to 89.17 In the United States outpatient visits from adults older than 65 years comprise 56% of the workload in ophthalmology, 54% in cardiology, and 46% in urology.18 The Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology predicts that one fifth of women cared for by obstetricians and gynecologists will be older than age 65 by 2030.19 The average age and number of comorbidities of elective surgical patients are increasing.20 Given these statistics, the service and resource implications of caring effectively for older patients are such that even those very few doctors who don’t interact at all with older adults in their clinical practice, such as pediatricians, will need to know enough about the core issues to effectively contend a place for their own discipline within the broader medical endeavor.

Clearly, though, the level of knowledge required by pediatricians is different from that required by general physicians, who are likely to see older patients as a routine part of their daily work. General physicians need to have competencies enabling them to safely provide basic care to older patients, while identifying opportunities for more specialized intervention. Specialist geriatricians, meanwhile, need to have competencies in frailty identification and management, in the coordination and facilitation of CGA, and in commonly presenting conditions of later life (e.g., falls, syncope, fractures, stroke, movement disorders, incontinence, cognitive impairment, and end-of-life care) to augment upon and support the work of more generalist colleagues. This leads to a three-tiered competency model as summarized in Figure 126-1.

Competencies Required by All Doctors

International agreement about the specifics of what should be taught is most advanced at the undergraduate level—the competencies required by all doctors—where a number of international curricula have been published.21 The International Association of Geriatrics and Gerontology (IAGG), through consultation with its 73 member organizations representing 65 countries, produced a guideline comprising 15 statements specifying minimum requirements for geriatric medical education in 2008. These guidelines are no longer available in print or online. There are, however, English language curricula specified by a number of national specialist societies; these organizations and links to curricula are given in Table 126-1.

TABLE 126-1

English Language Undergraduate Curricula in Geriatric Medicine

| Organization | Web Link to Curriculum |

| Association of American Medical Colleges | http://www.pogoe.org/Minimum_Geriatric_Competencies |

| Australia and New Zealand Society for Geriatric Medicine | http://www.anzsgm.org/documents/PositionStatementNo4-Revision.pdf |

| British Geriatrics Society | http://www.bgs.org.uk/index.php/medicalstudentstop/959-undergraduatecurriculum8 |

| Canadian Geriatrics Society | http://www.canadiangeriatrics.ca/default/assets/File/CGS_Competencies.pdf |

| Union of European Medical Specialists | http://ageing.oxfordjournals.org/content/43/5/695 |

In the United States, a consortium of geriatrician educators used an iterative multistage approach to develop a list of core competencies for foundation-level doctors called the “keeping granny safe” competencies.22 Starting from a literature review of U.S. curricula in geriatrics, they identified 52 non–mutually exclusive geriatric competency domains. They then conducted an iterative process with four stages: experts and broader stakeholders in geriatric medicine were asked to score domains in order of importance, and the top eight were selected; core competencies were written by the steering group to match the selected domains; an electronic survey further reduced the list; and final agreement on 26 competencies was made at a national stakeholder conference.

In the United Kingdom, a literature review identified English language curricula in geriatric medicine and gerontology, which were then presented at a consensus conference involving the national societies for geriatric medicine, biogerontology and social gerontology, and a research collaboration representing gerontechnologists.23 A core curriculum was agreed and then mapped to the core specifications stipulated in Tomorrow’s Doctors, the generic statutory guidance about undergraduate medical training in the United Kingdom. The resulting curricular map became the Recommended Curriculum for Undergraduate Teaching specified by the British Geriatrics Society (BGS).24

The European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) used the BGS curriculum as the basis for a modified Delphi consensus procedure in 2013. Three Delphi rounds were conducted, involving 49 experts from 29 countries, and complete agreement was reached following the third round. The final curriculum consisted of detailed objectives grouped under 10 overarching learning outcomes.25

By nature of their evolution, the U.K. and EU curricula map closely to each other and to previously published guidelines from Australasian and U.S. specialty societies. Work has yet to be undertaken to compare these to the more recent 26 U.S. competencies or to the Canadian curriculum. It may be, though, that the basis of international consensus lies in comparing the EU and U.S. recommendations and identifying core overarching themes.

Competencies Required by Specialist Geriatricians

Consensus is more limited about the core skill set required for doctors to become specialists in geriatric medicine. Freely available English language postresidency training curricula are available from a number of nations; links to these are provided in Table 126-2.

TABLE 126-2

English Language Curricula for Postresidency Training in Geriatric Medicine

| Organization | Web Link to Curriculum |

| American Geriatrics Society and Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs | http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jgs.12821/full |

| Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board and British Geriatrics Society | http://www.jrcptb.org.uk/specialties/geriatric-medicine |

| Royal Australasian College of Physicians | https://www.racp.edu.au/page/specialty/geriatrics |

| Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada | http://www.royalcollege.ca |

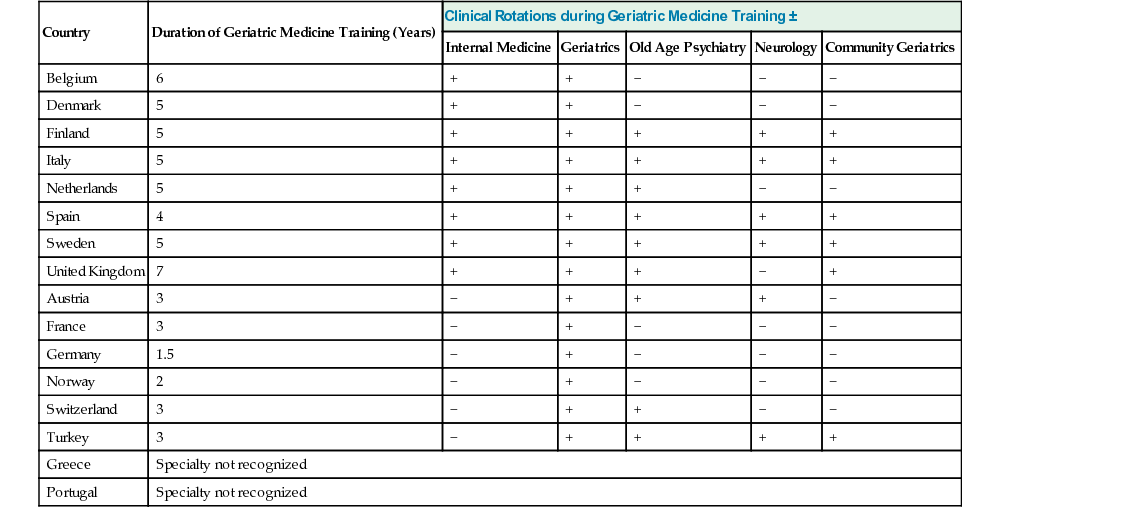

A recently published review of postgraduate training in geriatric medicine across 16 European countries26 revealed that programs vary substantially in duration, from 1.5 to 7 years, and that geriatric medicine remains unrecognized in a number of developed health care economies (Table 126-3). The UEMS–Geriatric Medicine Section has set an objective of coordinating consensus regulations for specialist training but recognizes “significant challenges” in doing so, given the considerable variability across member nations.

International training programs have emerged through the European Academy for Medicine of Ageing (EAMA),27 established under the aegis of professors from Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom in the 1990s and running regular courses since then, and the five master classes run by the IAGG in Asia between 2011 and 2014.28 However, these have focused very much upon establishing a cadre of international leaders, researchers, and teachers in geriatric medicine rather than equipping a large number of doctors with specialist skills to substantively move forward service developments in their respective regions. Clearly opportunities exist to replicate the consensus exercises undertaken around undergraduate teaching. Although one size is unlikely to fit all, the needs of patients are likely to be relatively similar across most settings and are unlikely to be served by broad variation in what it means to be a specialist geriatrician.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree