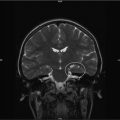

Fig. 30.2

(a) Risk assessment worksheet 1. (b) Risk assessment worksheet 2

Instead of lecture format, the team engages the survivors through an active question and answer session, as well as through various visual and hands-on activities. Survivors are instructed how to build the skills necessary to understand their treatment summary, and be able to identify risks for late effects. The primary goal for these activities are to spark survivor interest and willingness to take charge of their healthcare, as well as empowerment to make informed and responsible decisions. At the end of this session, a short survey is handed out to evaluate the effectiveness of the activities.

30.2.2 Psychosocial Advocacy

While numerous survivors are able to manage their daily routines, there is a subset of survivors who experience long-term challenges in several areas of their lives. Research shows that the cancer experience complicates the challenges faced by adolescents in areas involving increasing autonomy, relationships, and the need to make decisions about education and career paths, which exert their effects in different ways at varying time points in an adolescent survivor’s life [4].

The Hyundai Cancer Institute at CHOC Children’s ACTS program recognized these psychosocial issues within our patient population. Survivors acknowledge that their childhood cancer experience has impacted social interactions, as well as communication and coping skills, among others. Recent literature alludes to the fact that a cancer diagnosis initiates a new life path and social role for a cancer survivor that extends over the remainder of his or her life, regardless of life expectancy [5].

The CHOC ACTS Psychosocial Advocacy curriculum was developed to educate survivors on the social impact of cancer on peers, family and sibling relationships. The goal of the module is to increase the survivors’ interest in managing their own psychosocial issues, improve family/sibling communication, and encourage emotional expression through healthy coping strategies. The curriculum highlights the contrasts between healthy and unhealthy ways of expressing emotion in relation to family and sibling dynamics. In addition, we encourage increased awareness in recognizing depression and/or anxiety, as well as seeking appropriate help if such signs are exhibited. The module consists of lectures, discussions, PowerPoint presentations, handouts, and interventions that specifically target the previously mentioned areas. The team provides skill-building strategies to identify the symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as the listing of resources available to survivors in the community. Information about contacting local mental health services for insured versus uninsured patients, and identification and ability to contact religious/spiritual support services, as well as general support groups (Livestrong, Stupidcancer.org, and Cure Search) are provided. Lastly, survivors are taught how to utilize specific techniques like journaling, positive affirmations, relaxation and guided imagery, and meditation strategies to improve coping.

The following activities are included:

1.

Ice Breaker Game– “Who Am I?”: Each person is assigned a celebrity name that is posted on his or her back. Participants are encouraged to ask questions that could be answered by a yes or no, until they have enough clues to guess each other’s identity. Young adult survivors often feel uncomfortable even in the presence of other survivors; icebreakers often ease them towards familiarity and provide a less threatening environment.

2.

Panel of Survivors: In an effort to offer participants the opportunity to hear about other survivors’ experiences, a panel of former patients share their journeys from diagnosis through long-term survivorship. We utilize five panelists, with histories of leukemia, lymphoma, and brain tumor, who are all young adults in different stages of psychosocial development, with some enrolled in college and some employed. The panelists discuss a variety of topics, including: body image, relationships, losses, education, and employment, as well as psychosocial struggles. Participants are given the opportunity to interact with the panel through shared experiences. All participants, including panel members, are then divided into two smaller groups to process their struggles, challenges, and the coping strategies they use. Social workers, child life specialists, and a psychologist (the Psychosocial Team) facilitate these group discussions and provide teaching regarding awareness of their personal and psychosocial needs. The team also provides mental health resources and academic scholarship information.

3.

Self–Care: The symposium ends with a meditation session guided by one of the Psychosocial Team members. Instrumental music is incorporated while a guided imagery script is read to the participants focusing on whatever theme is derived, such as acceptance, healing, connectedness, etc. Each participant is provided with a relaxation kit that includes a guided imagery script, an instrumental music CD, and a list of mental health resources.

30.2.3 The Cancer Survivor and His/Her Loved Ones

As demonstrated throughout this manuscript, cancer not only affects the patient physically, spiritually and emotionally, but the entire family as well. Family and other interpersonal relationships may become stressed and strained due to the loved one’s illness. In this difficult time, relationships are often challenged by a need for improved communication, acknowledgement, and expression of feelings, and desire for normal routine. When cancer finds its way into a family, the relationships between all members are affected. Studies have shown that among family members, siblings are most affected [6]. Siblings typically experience intermittent and sometimes lengthy family separation and disruptions of their daily routine [6], which often results in decreased social contact with important sources of emotional and social support, such as parents and peers [7].

The ultimate goal of this module is to enable survivors and siblings to understand the social effects and implications of cancer on peers, family, and specifically, relationships between brothers and sisters. It is important for survivors and their siblings to understand the common reactions to cancer and to gain insight about the experiences of the other members of their family. We also aim to highlight the following goals: enhancing positive coping skills, utilizing effective ways of communicating with loved ones, practicing self-care, and learning how to access mental health resources if needed. Survivors may not recognize the repercussions of their cancer experience on their relationships with their loved ones. But by helping the survivor and siblings become aware of these psychosocial issues, and by providing them with the appropriate tools, both parties can work towards building a closer and more meaningful relationship with one another.

For this workshop, cancer survivors are encouraged to invite their siblings. We began with an ice breaker in which participants are asked to describe a favorite memory regarding their sibling(s). Oftentimes siblings choose memories that precede the illness, while others choose newer memories. Of note, it is our experience that some siblings recall few pleasant memories after their sibling was diagnosed with cancer. Others share more recent memories, stating that the diagnosis has brought them closer to their brother or sister.

After sharing these memories, the psychologist presents on “Life after Cancer: Childhood Cancer Survivors and their Siblings.” This presentation serves as a catalyst for the upcoming group discussions. The following discussion topics are included: common emotions felt between survivors and siblings during and after treatment, adjustment post-cancer, changes that have occurred within their family relationships, coping with those very changes, caring for oneself, and planning for one’s future and knowing ways to find help and support.

Participants are then divided into two groups, one group consisting of the siblings, and the other consisting of survivors. A child life specialist and psychologist address the siblings and asked them a series of questions to help facilitate conversation, and to discuss the emotional impact felt during their sibling’s treatment. Both negative and positive emotions are recorded on an easel so they could be later shared with the larger group. Themes that siblings have discussed in previous workshops include feelings of neglect, anger, anxiety, and isolation, with some siblings confiding that they believed themselves to have grown up too quickly because their parents were not around most of the time. According to Breyer et al., a disruption occurs in the routine of family life and in the allocation of parents’ time, attention and resources [8]. Siblings often speak of missing activities and events with their own friends. They express being fearful at the time of diagnosis, often not being given much information. They indicate that they typically keep their fears to themselves, refraining from asking too many questions, because they do not want to be a burden to their parents.

Children, as compared to adults, are more likely to report communication difficulties and declining of family relationships [8]. Siblings express feelings of guilt because of the jealousy felt toward their sibling at the time of diagnosis due to all the attention and gifts that were showered upon the patient. Many siblings admit that some of those feelings still exist and remain unresolved. Even though anger and sadness often accompany family trauma and upheaval, some siblings may develop a new understanding of illness, a closer relationship with their ill sibling or an increased maturity and understanding about others’ misfortunes [8]. Siblings also share positive experiences, such as becoming closer as a family by overcoming obstacles, celebrating milestones and becoming more compassionate toward others in their own lives.

The social worker and the oncologist leads the second group. Survivors vary in diagnoses and each share different challenges they each had to overcome, and express both positive and negative emotions concerning their sibling and other loved ones. Survivors often mention a loss of control, an inability to socialize with friends or to participate in “normal” activities and feeling less connected to their families while undergoing treatment. The survivors express how guilty and burdensome they felt about the sacrifices their family and siblings had to make during their cancer journey. They also express not wanting their family to suffer if a relapse were to occur. Concern about disease recurrence is universal among adolescent survivors, and its presence may adversely affect the way adolescents perceive themselves [9]. Survivors talk about feeling vulnerable—a simple fall, cold, or bump they felt on their body remind them anew of the possibility of relapse. They state that this kind of feeling never really leaves them.

Survivors are asked what positive attributes they could identify within themselves, having accomplished and endured so much during and after treatment. Common characteristics often mentioned include strength and resilience, and survivors are often shocked to see that strength and resilience within themselves. Investigators sometimes report certain beneficial outcomes in individuals as a result of diagnosis and treatment, such as gaining insights and supportive experiences they would not have anticipated before diagnosis [10]. Previous classes have revealed that the emotional support from family, friends, and individual’s communities not only helped them, but also their parents and siblings as well. Survivors speak of the difficulty of finding out that many friends had left them due to an inability to handle the situation. Some mentioned that they grew closer to siblings during this period because they did not always have peer support. Others state that they felt angry because of their illness, and as a result pushed siblings and loved ones away.

This often leads into a discussion about difficulties of life after cancer. Survivors have expressed that integrating and adjusting back to normal life was challenging. The issue of fatigue is a frequent theme. An illness frequently disrupts peer interaction because of observed physical differences and limitations [11]. Survivors have reported feelings that they were still treated like “the sick one” by friends and family. Feelings of anxiety and concern are expressed about their quality of life, especially when it comes to friends, dating, body image, and having a family of their own someday. Many survivors said that they felt they were no longer the same person they were before their illness, sometimes having trouble relating to others, including their siblings. All survivors, even those apparently doing quite well, continue to be concerned about their physical, psychological and social qualities of their current and future relationships [12].

The two groups are then joined together to discuss what had transpired in the separate sessions. Child life and social work lead the discussion to help lessen the pressure of starting these conversations themselves, and the feelings and concerns written on the easels are shared. It is our experience that after some discussion, siblings often express that they did not realize the survivors felt a sense of guilt and burden that the family was suffering at the time of diagnosis, and express having a new understanding of what the survivor went through at the time. Siblings report a greater understanding of survivorship concerns such as anxiety and continued fatigue. On the other hand, survivors often state that they did not realize that their siblings held feelings of continued guilt, as well as jealousy. Both groups have expressed feelings of resentment toward one other, which neither of the parties realized. For many, this is the first time they hear of the feelings and pains the other feels. They also express feelings of love and appreciation for each other, stating that their sibling had often been there during the worst of times. Past groups have given positive feedback about the discussion, feeling they had found a greater appreciation for their siblings, and expressed wanting to have a closer relationship with the other.

We end with a group activity and handouts. Handouts are centered on communication skills, how to take care of oneself, and how to access mental health resources. The group activity is meant to affirm and acknowledge each person’s journey. Bins of different colorful textured beads are laid out around the room, and each is able to pick a bead that they feel represents their sibling in some way. They are asked to describe on paper how the beads remind them of their siblings. The beads and notes are then put into envelopes and given to the siblings so that they could be opened at home. The purpose of this exercise is for every participant to know how much they mean to those around them and to encourage the use of the beads during difficult times to help reflect on the support of their sibling.

30.2.4 General Nutrition

Healthy eating is one clear pathway that leads to healthy lifestyle. For example, knowing that food high in fat and sugar can lead to undesirable weight gain and potential health problems allows survivors to make choices for the benefit of their bodies. The objectives of this module include educating survivors about up-to-date nutritious needs based on USDA recommendations, as well as developing beneficial lifestyles. Preventative options to lessen health risks will also be discussed in great detail. The module incorporates appealing, hands-on exercises with meal options and proportion size, as well as ways to care for both body and mind through exercise and meditation.

There are various resources available, including websites such as: ChooseMyPlate.gov [13], a website which contains the tools and information to tell us what and specifically how much we should eat. This site provides recommendations based on the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Dietaryguidelines.gov) [14], which cites portion sizes for different food groups as they relate to the individual’s caloric and nutrient needs. The website outlines individual eating patterns that fit into different lifestyles and food preferences.

The ‘MyPlate’ Icon is the United States Drug Agency’s (USDA) primary food group symbol, a reminder to select healthy food choices and to build a healthy plate at mealtimes. It is a visual cue which identifies the five basic food groups necessary for healthy living. Half of the plate must be filled with fruits and vegetables, and the remainder should consist of whole grains and lean proteins.

Other important tips also emphasized in the MyPlate Plan:

1.

Drink water instead of sweetened drinks

2.

Choose low-fat milk

3.

Choose foods that are lower in sodium

4.

Use moderation in foods that are high in fat or sugar such as cookies, cakes, pizza, or hot dogs

Reading the food label on the product itself can help us make wise choices in consuming. Knowing how to read labels, and what to look for, helps us select provisions that are low in fat, calories, and sugar. Lastly, labels can help us determine how much of a food item is considered a healthy portion in serving size, influencing the number of servings for that particular food item a person should have.

The healing effects of alternative treatments, such as aromatherapy and acupuncture, are also discussed. A licensed acupuncturist is invited to facilitate this session. Finally, recreation time for art, music, and physical activities is provided.

30.2.5 Insurance, Education, and Employment

Survivors of childhood cancer may well face a variety of challenges related to insurance, education, and employment. These issues may have a profound effect on quality of life, encompassing both the physical and psychosocial well-being. While these issues are addressed elsewhere in this manuscript, a brief review is provided for purposes of highlighting how it is addressed in the curriculum.

Health insurance coverage is a weighty topic of concern for all Americans but especially so for cancer survivors. Such individuals require lifelong surveillance for and management of the late effects of their disease or treatment. Insurance policies, qualifications, and legal issues are confusing, complex, and ever changing. During the transition from adolescence to adulthood, survivors have a need to become more involved in the process of how their healthcare is acquired, funded, and managed. Understanding the variety of different types of options and laws regarding health care insurance is invaluable for the young adult cancer survivor, so that he or she may become an informed and responsible consumer of health care.

Many childhood cancer survivors experience educational challenges related to neurocognitive deficits resulting from their disease or therapy. The types of intellectual functions affected may result in deficits in memory, attention, and executive function, as well as processing speed and language skills. The level of disability may range from mild to severe. Multiple factors influence the ultimate neurocognitive outcome of survivors. These factors include: diagnosis, age at diagnosis, type of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, intrathecal chemotherapy, radiation therapy, etc.), pre-treatment factors, length of time since treatment, and gender [15].

In the United States, there are certain Federal laws in place to protect the rights of students with educational problems ensuing from cancer treatment. These are discussed in more detail elsewhere in this manuscript, but a brief summary is provided herein:

1.

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973—Section 504. The law provides accommodations for students with a “physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.” Each childhood cancer survivor in the United States is eligible for accommodations under this law, and all schools, colleges and universities which receive federal funding are required to comply [16].

2.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). This law ensures services to children and youth with disabilities throughout the nation. IDEA governs how states and public agencies provide early intervention, special education and related services [17]. It is necessary for survivors to have a well-rounded understanding of the potential educational issues related to their disease and treatment, as well as their rights as related to ongoing education. For childhood cancer survivors who do not plan to or are unable to attend college, additional resources may be available for vocational training or rehabilitation. These resources are managed individually by each state. To contact your state’s vocational rehabilitation, visit your state’s governmental website at www.<your state’s abbreviation>.gov [18].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree