The benefits that are reported in patients who have carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer increase as the extent of disease within the abdomen and pelvis decreases. To optimize treatments that involve cytoreductive surgery and perioperative chemotherapy, early intervention is necessary. Strategies to improve the results of carcinomatosis treatments include second-look surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients at high risk for recurrence. Alternatively, the use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy can be used to treat or prevent carcinomatosis at the time of primary colorectal cancer resection in selected patients.

- •

Peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancer can be cured, similar to lymph nodal metastases, liver metastases, and pulmonary metastases.

- •

The extent of disease, in large part, determines the success that can be expected with cytoreductive surgery and perioperative chemotherapy treatments.

- •

Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy can be used as part of the management of primary colorectal cancer presenting with peritoneal metastases.

- •

The hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy treatments must evolve so that they are capable of preserving the surgical complete response that is achieved with cytoreductive surgery.

Introduction

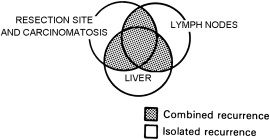

Currently, the standard of care for advanced primary colorectal cancer involves treatments that are nearly identical for all patients. A routine surgery is followed by a routine systemic chemotherapy. A routine follow-up by physical examination and computed tomography (CT) then occurs. If symptoms or CT findings suggest a localized recurrence, a palliative surgery is followed by second-line chemotherapy. This plan fails to recognize that the primary disease is a complex process and that the anatomic sites of initial treatment failure vary greatly between individuals Fig. 1 diagrams the directions for metastases when primary surgery fails. The goal of this report is to establish new guidelines for the individualized management of those patients who are likely to have progression of resection site disease and/or carcinomatosis as the initial site of treatment failure.

Rationale for a new strategy of early intervention

The combination of cytoreductive surgery with perioperative chemotherapy has become a treatment option for selected patients with peritoneal dissemination of colorectal cancer. It is well documented that the results of treatment vary greatly with the clinical status of the patient. Quantitative prognostic indicators have been established that allow the oncologist to inform the patient regarding the likelihood of long-term benefit. One of these prognostic indicators is the completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score; for colorectal cancer a complete cytoreduction indicates that the surgery was effective in clearing all visible evidence of disease (CC-0) or left behind only a few minute deposits of cancer that are expected to be eradicated by perioperative local-regional chemotherapy (CC-1). Complete cytoreduction includes both CC-0 and CC-1 cytoreduction. A necessary (but not sufficient) requirement for long-term benefit is complete cytoreduction. A potentially curative treatment for colorectal peritoneal dissemination does not occur in the absence of a complete cytoreduction.

A second useful quantitative prognostic indicator is the peritoneal cancer index (PCI). This prognostic indicator scores both the distribution and extent of carcinomatosis in 13 abdominal and pelvic regions to arrive at a quantitative assessment of the extent of carcinomatosis. The PCI predicts the likelihood of an incomplete cytoreduction; also, it predicts long-term survival even though the cytoreduction is complete. A low PCI, indicating a limited extent of carcinomatosis, is associated with an improved prognosis. Elias and colleagues, in a French collaborative study of 523 patients, reported a 50% survival rate at 5 years with PCI of 6 or less, 27% rate with PCI between 7 and 19, and less than 10% rate with PCI greater than 19. He suggested that an attempt at complete cytoreduction with a PCI greater than 20 should occur only under special circumstances, such as a young and fit patient.

These 2 prognostic indicators taken together indicate that the extent of carcinomatosis has a profound effect on the outcome when this manifestation of metastatic disease is treated with cytoreductive surgery and perioperative chemotherapy. A reliable concept worthy of pursuit states that the likelihood of long-term survival will continue to improve as extent of disease as measured by PCI decreases. The clinical correlate of this concept is that definitive treatment early in the natural history of carcinomatosis can be expected to optimize survival benefit.

Support for this concept of early intervention with a small volume of carcinomatosis can be found in the oncology literature. Recently, Elias and colleagues reported on a new plan for early intervention in patients with a high risk for local-regional recurrence after primary colon cancer surgery with small volume peritoneal seeding, ovarian metastases, or perforation through the primary cancer. After treatment with systemic chemotherapy, the patients were taken back to the operating room for a “systematic second look surgery.” Return for reoperation occurred within 1 year. At exploration, Elias found cancer present in 16 (55%) of the 29 patients who had repeat surgical intervention. All patients with progressive disease were treated with cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. At 27-month median follow-up, the survival of patients with cancer found at second look was 50%. The high incidence of prolonged survival in this group of patients with early definitive intervention supports the concept of maximal benefit in patients with minimal disease.

This concept of increasing benefits with reduced extent of disease may be a valid concept throughout oncology. It is the basic hypothesis that drives the TNM system. Certainly, it operates definitively with colorectal liver metastases. The greater the number of deposits resected from the liver, the poorer is the prognosis; this is true even though an R0 liver resection is achieved. Perhaps it is not surprising that this concept of increasing benefits with a lesser extent of disease is important for interpreting the results of treatment with colorectal carcinomatosis.

An important clinical question concerns the rational application of this concept to the management of colorectal cancer, especially patients with carcinomatosis. Currently, the results of treatment of a population of carcinomatosis patients are guarded – often not accepted, because the risks of treatment are perceived to exceed its benefits. In current practice, these patients must submit to a major surgical intervention with an extended hospitalization and long convalescence. Unfortunately, within a few months or years, a majority (estimated at 70%) recur within the abdomen or pelvis, have no further treatment options, and go on to die.

If cytoreductive surgery and perioperative hyperthermic chemotherapy represent an accepted treatment modality, and the author believes that it is, then its application should be modified to maximize benefits. It is possible that the concept of early intervention for carcinomatosis treatment can be brought into the management strategies for colorectal carcinomatosis. This can be done by integrating the concepts of second-look surgery, treatments with cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy, and risk of local-regional disease progression.

Rationale for a new strategy of early intervention

The combination of cytoreductive surgery with perioperative chemotherapy has become a treatment option for selected patients with peritoneal dissemination of colorectal cancer. It is well documented that the results of treatment vary greatly with the clinical status of the patient. Quantitative prognostic indicators have been established that allow the oncologist to inform the patient regarding the likelihood of long-term benefit. One of these prognostic indicators is the completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score; for colorectal cancer a complete cytoreduction indicates that the surgery was effective in clearing all visible evidence of disease (CC-0) or left behind only a few minute deposits of cancer that are expected to be eradicated by perioperative local-regional chemotherapy (CC-1). Complete cytoreduction includes both CC-0 and CC-1 cytoreduction. A necessary (but not sufficient) requirement for long-term benefit is complete cytoreduction. A potentially curative treatment for colorectal peritoneal dissemination does not occur in the absence of a complete cytoreduction.

A second useful quantitative prognostic indicator is the peritoneal cancer index (PCI). This prognostic indicator scores both the distribution and extent of carcinomatosis in 13 abdominal and pelvic regions to arrive at a quantitative assessment of the extent of carcinomatosis. The PCI predicts the likelihood of an incomplete cytoreduction; also, it predicts long-term survival even though the cytoreduction is complete. A low PCI, indicating a limited extent of carcinomatosis, is associated with an improved prognosis. Elias and colleagues, in a French collaborative study of 523 patients, reported a 50% survival rate at 5 years with PCI of 6 or less, 27% rate with PCI between 7 and 19, and less than 10% rate with PCI greater than 19. He suggested that an attempt at complete cytoreduction with a PCI greater than 20 should occur only under special circumstances, such as a young and fit patient.

These 2 prognostic indicators taken together indicate that the extent of carcinomatosis has a profound effect on the outcome when this manifestation of metastatic disease is treated with cytoreductive surgery and perioperative chemotherapy. A reliable concept worthy of pursuit states that the likelihood of long-term survival will continue to improve as extent of disease as measured by PCI decreases. The clinical correlate of this concept is that definitive treatment early in the natural history of carcinomatosis can be expected to optimize survival benefit.

Support for this concept of early intervention with a small volume of carcinomatosis can be found in the oncology literature. Recently, Elias and colleagues reported on a new plan for early intervention in patients with a high risk for local-regional recurrence after primary colon cancer surgery with small volume peritoneal seeding, ovarian metastases, or perforation through the primary cancer. After treatment with systemic chemotherapy, the patients were taken back to the operating room for a “systematic second look surgery.” Return for reoperation occurred within 1 year. At exploration, Elias found cancer present in 16 (55%) of the 29 patients who had repeat surgical intervention. All patients with progressive disease were treated with cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. At 27-month median follow-up, the survival of patients with cancer found at second look was 50%. The high incidence of prolonged survival in this group of patients with early definitive intervention supports the concept of maximal benefit in patients with minimal disease.

This concept of increasing benefits with reduced extent of disease may be a valid concept throughout oncology. It is the basic hypothesis that drives the TNM system. Certainly, it operates definitively with colorectal liver metastases. The greater the number of deposits resected from the liver, the poorer is the prognosis; this is true even though an R0 liver resection is achieved. Perhaps it is not surprising that this concept of increasing benefits with a lesser extent of disease is important for interpreting the results of treatment with colorectal carcinomatosis.

An important clinical question concerns the rational application of this concept to the management of colorectal cancer, especially patients with carcinomatosis. Currently, the results of treatment of a population of carcinomatosis patients are guarded – often not accepted, because the risks of treatment are perceived to exceed its benefits. In current practice, these patients must submit to a major surgical intervention with an extended hospitalization and long convalescence. Unfortunately, within a few months or years, a majority (estimated at 70%) recur within the abdomen or pelvis, have no further treatment options, and go on to die.

If cytoreductive surgery and perioperative hyperthermic chemotherapy represent an accepted treatment modality, and the author believes that it is, then its application should be modified to maximize benefits. It is possible that the concept of early intervention for carcinomatosis treatment can be brought into the management strategies for colorectal carcinomatosis. This can be done by integrating the concepts of second-look surgery, treatments with cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy, and risk of local-regional disease progression.

Historical review of second-look surgery for colorectal cancer

In 1948, Wangensteen at the University of Minnesota initiated a new plan he hoped would improve the management of intra-abdominal cancer. He reasoned that surgery was the only effective tool by which to cure primary gastrointestinal cancer; therefore, more radical cancer surgery could be an adjuvant treatment used to extirpate isolated sites of disease progression and thereby improve survival. He identified lymph node–positive disease at the time of primary cancer resection as an indication for a systematic plan of reoperation. In selected patients at 6- to 8-month intervals, surgical reexploration of the abdomen and pelvis was performed. Reoperations were scheduled until no cancer was found or until the disease was beyond surgical control. Initially, patients were only taken to surgery in an asymptomatic state; however, as the clinical results from the reoperative treatment strategies evolved, patients with symptoms from recurrent disease were included in the series.

Table 1 presents the results of second-look surgery for colon cancer after 20 years of data accumulation. In 36 patients who had Cancer progression documented (positive second look), 6 (17%) patients were “converted” from a second look positive to a long-term disease-free status. In 47 patients who had a symptomatic second look, 7 (15%) patients were converted by reoperative surgery to long-term survival. In their review of these data from the second-look approach, Griffin and colleagues concluded that “significant patient survival resulted from the second look approach in patients with cancer of the colon. This effort should be continued and extended.”

| Second-Look Negative | Second-Look Positive | Symptomatic Look | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 62 | 36 | 47 |

| Operative deaths | 2%–3.2% a | 6%–17% | 7%–15% |

| Recurrent cancer b | 12%–19% | 24%–67% | 33%–70% |

| Living and well, last look negative | 41 | 4 | 4 |

| Living and well, last look positive | – | 0 | 3 |

| Living with residual | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Dead from other than cancer | 10 | 2 | 0 |

| Total converted | – | 6%–17% | 7%–15% |

a One patient had residual cancer and died at fifth look.

Benefits for patients “converted” from a positive second look to long-term survival were offset, at least in part, by the impact this management plan had on the entire group of patients. Extensive surgical procedures to remove recurrent disease led to an operative mortality of 17% in the patients who had a positive second look. Also, in the patients with the symptomatic second look, there was a 15% operative mortality. In interpreting these mortality statistics, one must realize that this high operative mortality occurred in patients identified as having progressive disease. These patients would presumably have gone on to die of this disease in the near future. However, their lives were cut short as a result of the second-look surgery.

Perhaps most worrisome for the surgeon performing planned second-look procedures were the 2 (3.2%) patients who died postoperatively after a negative exploration. These patients dying with a negative second-look result may have been long-term survivors in the absence of this aggressive surgical treatment strategy.

There have been efforts to expand the indications for second-look surgery. In the mid-1970s, a collaborative effort of the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and the Mallory Gastrointestinal Laboratory searched for clinical relationships between the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and the natural history of surgically treated colorectal cancer. Sugarbaker and colleagues determined that serial CEA assays determined at 3-month intervals after a colon or rectal cancer resection would detect occult recurrent disease approximately 6 months before clinical signs and symptoms. These results led to a clinical study to use CEA as a surveillance test for recurrent colon or rectal cancer after a potentially curative cancer resection. Steele and colleagues reported on a prospective study of 75 patients who had CEA assays performed at approximately 2-month intervals. Fifteen of 18 tumor recurrences were first diagnosed by increasing CEA values despite no other evidence of progressive disease. In 4 of these 15 patients, complete resection of recurrent cancer with a potential for cure was reported. Long-term follow-up of the total number of patients “converted” from recurrent disease to long-term survival was not available.

Attiyeh and Sterns presented data on 32 patients who underwent second-look surgery for “a significant CEA elevation” following a curative resection for adenocarcinoma of the large bowel. The total number of patients from whom these 32 with an increasing CEA blood test were selected was not available. These 32 patients underwent a total of 37 exploratory procedures with 16 (43%) of 37 potentially curative resections. Again, the number of patients “converted” from recurrent disease to long-term survival was not available from this report.

Additional data regarding the possible benefits of second look surgery in colorectal cancer patients comes from the prospective evaluation of this strategy reported in 1985. Minton and colleagues initiated a multi-institutional study. They prospectively collected data on 400 patients operated on at 31 different institutions. Their results emphasize that the surgeons performing the second-look surgery had advanced training in reoperative surgery. These 400 patients had 43 CEA-directed reoperations and 32 symptomatic second-look reoperations. At 5 years after the second-look surgery, 22 (29%) of 75 patients remained disease free. Minton and colleagues, as a result of their study, recommended meticulous clinical surveillance of Dukes’ stage C2 cancer following primary colorectal cancer resection, CEA determinations at 1- to 2-month intervals postoperatively, and second-look surgery before serial CEA testing exceeded 11 ng/mL.

As a result of these efforts to use postoperative monitoring of CEA in patients at high risk for recurrence of colon and rectal cancer, a standard of practice has evolved in patients surgically treated for colorectal cancer. If a progressive increase in the CEA blood test occurs, patients should be considered for reoperation. Radiologic tests should be performed to show that the elevated CEA determination occurs in the absence of systemic disease or unresectable disease within the abdomen or pelvis. Minton and colleagues should be credited with establishing a strong rationale for meticulous follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer and a reasonable likelihood of benefit from second-look surgery.

Goldberg and coworkers collected data in a prospective follow-up of 1247 patients with resected stage 2 or stage 3 colon cancer ; 548 patients had recurrence of colon cancer and second-look surgery was attempted in 222 (41%) patients. In 109 (20%) patients, potentially curative surgery resulted. In patients who came to curative intent second-look surgery, recurrent disease was identified by radiologic follow-up in 36 patients, serial CEA tests in 41 patients, and symptoms in 27 patients. The 5-year disease-free survival of these 109 patients was 23%. The surgical mortality was 2%. These authors concluded that early reoperation as a result of careful postoperative follow-up testing of patients with colon cancer may identify recurrent disease in some and that the second-look surgery can result in a long-term disease-free survival.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree