Dysmenorrhea and Premenstrual Disorders

Paula K. Braverman

KEY WORDS

Drospirenone

Dysmenorrhea

Endometriosis

Leukotriene

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD)

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

Prostaglandin

Female adolescents and young adults (AYAs) commonly experience menstrual dysfunction. Both dysmenorrhea and premenstrual disorders (PMDs) (premenstrual syndrome [PMS] and premenstrual dysphoric disorder [PMDD]) affect women to some extent during their lifetime. Research into the etiology of these menstrual disorders has led to improved therapies. Experts have also been moving toward consensus opinion for the diagnosis of PMDs in order to facilitate clinical diagnosis and research into therapeutic options. This chapter reviews the epidemiology, etiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment options currently available for these menstrual disorders.

The term “primary dysmenorrhea” refers to pain associated with the menstrual flow, with no evidence of organic pelvic disease. “Secondary dysmenorrhea” refers to pain associated with menses secondary to organic disease such as endometriosis or outflow tract obstruction.1

Etiology

Prostaglandins

Prostaglandins are formed in the secretory endometrium. Phospholipids from cell membranes are converted into arachidonic acid, the fatty acid precursor for prostaglandin synthesis. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and PGF2α, which are formed through the cyclooxygenase pathway, are the key prostaglandins involved in dysmenorrhea, although PGF2α is considered the most important. PGF2α induces myometrial contractions, vasoconstriction, and ischemia and mediates pain sensation, whereas PGE2 causes vasodilation and platelet disaggregation. There are two enzymes in the cyclooxygenase system. The COX-1 enzyme has homeostatic functions, including gastrointestinal mucosal integrity, renal and platelet function, and vascular hemostasis. COX-2 is induced by inflammation.1,2 It has been noted that:

Locally, prostaglandins cause uterine contractions, but they enter the systemic circulation and cause associated symptoms such as headache, nausea, vomiting, backache, diarrhea, dizziness, and fatigue.

Exogenous administration of PGE2 and PGF2α produce myometrial contractions and pain similar to dysmenorrhea.

Anovulatory cycles are associated with lower prostaglandin levels in the menstrual fluid and usually no dysmenorrhea. Because many cycles in the first 2 years after menarche are anovulatory, many adolescents do not experience dysmenorrhea from the outset. Rather, it occurs more frequently 1 to 3 years after menarche.

Patients with dysmenorrhea have higher levels of prostaglandins in the endometrium.

Most of the prostaglandins are released in the first 48 hours of menstruation, correlating with the most severe symptoms.

Prostaglandin inhibitors decrease dysmenorrhea.

This evidence supports the hypothesis that primary dysmenorrhea is related to prostaglandins released during menses, which seem to be increased during ovulatory cycles. It is postulated that women with dysmenorrhea may be more sensitive to prostaglandins. The upregulation of COX-2 expression and subsequent production of prostaglandin levels have also been shown to be present in secondary dysmenorrhea caused by endometriosis.1,2

Leukotrienes

Leukotrienes (LT) which mediate the inflammatory response are produced from arachidonic acid through the lipoxygenase pathway. LT receptors are present in uterine tissue, and a correlation has been found between LT C4 and D4 (two types of LT) levels and the severity of symptoms in primary dysmenorrhea.2,3

Other Factors

A meta-analysis showed that age (<30 years), low body mass index, smoking, earlier menarche (<12 years), longer cycles, heavy menstrual flow, nulliparity, and psychological symptoms were associated with dysmenorrhea.4

Epidemiology

Dysmenorrhea is a significant cause of lost work and school hours in adolescent girls and young adult women. Various studies worldwide have shown the following3,5:

About 48% to 93% of all postpubescent females have some degree of dysmenorrhea; between 5% and 42% of these females describe the pain as severe; and 14% miss two or more days of school per month.

Reports of school absence increase with more severe symptoms; dysmenorrhea also affects other activities, including sports, socialization, and sleep.

Approximately 10% to 50% of women lose work days due to dysmenorrhea, which has socioeconomic impact.

Many AYA women do not report dysmenorrhea symptoms to a clinician.

A survey of 12- to 21-year-olds in an urban adolescent clinic found that only 2% reported receiving information about menstruation from a health care provider.6

Clinical Manifestations

Primary dysmenorrhea usually begins within 1 to 3 years of menarche and is associated with the establishment of ovulatory cycles. Although the pain usually begins within a few hours of starting menses, it may also start several days before the onset of menses. Local symptoms include pain that is spasmodic in nature and is strongest in the lower abdomen, with radiation to the back and anterior aspects of the thighs. In most cases, the pain resolves within 24 to 48 hours, but sometimes the symptoms may persist further into the menstrual cycle. Associated systemic symptoms can include nausea or vomiting, fatigue, mood change, dizziness, diarrhea, backache, and headache.1

Differential Diagnosis

Gynecologic Causes

These include endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, benign uterine tumors (fibroids), intrauterine devices, anatomic abnormalities (congenital obstructive mullerian malformations, outflow obstruction), pelvic adhesions, ovarian cysts, masses or torsion, and pregnancy complications (miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy).

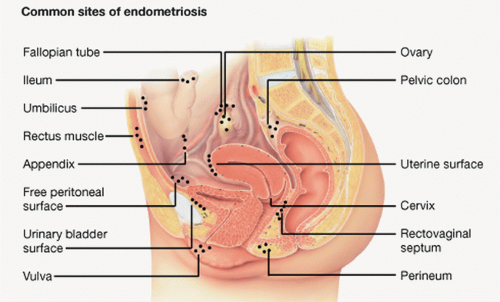

Endometriosis (Fig. 47.1) is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside of the uterus. These implants are commonly located in various locations throughout the pelvis. This condition is not as rare in adolescents as previously thought. In addition to being the most common pathologic condition in adolescents with chronic pelvic pain, it is considered a progressive disease that increases in prevalence and severity with age. Endometriosis has been diagnosed by laparoscopy in 19% to 73% of adolescents being evaluated for chronic pelvic pain and in 50% to 70% of adolescents not responsive to oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).1,9

FIGURE 47.1 Endometriosis. (From Endometriosis. In Lippincott’s Nursing Advisor 2012. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012.)

The symptoms of endometriosis in adolescents include chronic pelvic pain, which may be cyclic or acyclic. Cyclic pain alone is found in only 9.4% of adolescents.9 This is in contrast to adults who are more likely to have cyclic pain. Other associated symptoms can include dyspareunia; irregular menses; bowel symptoms such as rectal pain, nausea, constipation, diarrhea, and pain on defecation; and urinary symptoms such as dysuria, urgency, and frequency.

On examination, a tender or nodular cul-de-sac or tender uterosacral ligaments may be found. However, adolescents may not have the classic thickened nodular sacrouterine ligaments. Endometriosis should be considered in patients with dysmenorrhea who do not respond to a combination of OCP and NSAID, as well as those with associated bowel or urinary function symptoms. This diagnosis is also more common when there is a positive family history for endometriosis, and there is a high rate of concordance in monozygotic twins. The inheritance is believed to be polygenic and multifactorial.1,2

Anatomical abnormalities include congenital obstructive müllerian malformations, outflow obstruction. Obstructive müllerian abnormalities predispose the patient to endometriosis.

Nongynecologic Causes

These include gastrointestinal disorders (inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, lactose intolerance), musculoskeletal pain, genitourinary abnormalities (cystitis, ureteral obstruction, calculi), and psychogenic disorders (history of abuse, trauma, psychogenic complaints).

Diagnosis

History

Menstrual history: Primary dysmenorrhea usually starts 1 to 3 years after menarche, most commonly begins between the ages of 14 and 15 years. Secondary dysmenorrhea should be considered if the pain starts with the onset of menarche or after the age of 20 years. AYAs should be asked about the degree of pain and the amount of impairment in school, work, and

other activities. Any previous use of therapeutic modalities and their effectiveness should be ascertained.

Other history: Additional questions should include prior sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and sexual activity; a review of systems related to the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and musculoskeletal systems; and a psychosocial history to assess stress, substance abuse, and sexual abuse.

Physical Examination

Examine the pelvis for evidence of endometriosis, endometritis, fibroids, uterine or cervical abnormalities, or adnexal masses and tenderness. However, if the teen or young adult is not sexually active and the history is typical for dysmenorrhea, a pelvic examination is indicated only if the symptoms do not respond to standard medical therapy. Examination limited to a cotton swab inserted into the vagina can help rule out a hymenal abnormality or vaginal septum without performing a speculum examination. The musculoskeletal examination should focus on range of motion of the hips and spine to assess for tenderness and limitation in motion.

Laboratory Tests

A complete blood count and a determination of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate should be done if pelvic inflammatory disease or inflammatory bowel disease is suspected. Sexually active AYAs should be tested for STIs and pregnancy. A urinalysis and urine culture will help diagnose urinary tract problems. If a müllerian abnormality is suspected, ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will define the anatomy. If evaluation of the genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal systems fails to reveal a cause of the pain, and if the pain is severe and intractable despite treatment with antiprostaglandins and oral contraceptives, laparoscopy should be considered.

Therapy

The two most effective treatments for primary dysmenorrhea are NSAIDs and hormonal contraceptives.

Education

The patient should be educated and reassured that the problem is physiological and can be helped. The importance of education has been demonstrated repeatedly in studies demonstrating that adolescents have a knowledge deficit about available treatment modalities and how to use them most effectively.5,7

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs are the primary modality of therapy; 80% of dysmenorrhea can be relieved with these medications. Because much of primary dysmenorrhea is secondary to prostaglandin-mediated uterine hyperactivity, prostaglandin inhibitors can alleviate menstrual cramps and associated systemic symptoms. Many NSAIDs have been found effective in alleviating menstrual cramps.1,2 Some of these drugs and their typical doses are found in Table 47.1.

Over-the-counter ibuprofen and naproxen are available, but because these over-the-counter medications come in lower doses than the prescription formulations, a larger number of tablets may be needed for effectiveness. The medications should be started either as soon as possible when the symptoms of dysmenorrhea occur or to coincide with the first sign of menstruation. It is not necessary to start before the onset of menses, but if there is early vomiting with severe pain, starting a few days prior to menses may be helpful.1 Usually, these medications are needed only for 1 to 3 days. After one of the NSAIDs is started, it should be tried for two or three menstrual cycles before being judged ineffective. At that time, a trial of a different prostaglandin inhibitor should be tried.

With the outlined doses of NSAIDs used for short periods, side effects are usually minimal. The NSAIDs in Table 47.1 inhibit both the COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes. However, selective COX-2 inhibitors will have less gastrointestinal side effects and may also be preferred in patients with coagulation disorders related to platelet function. Because of drug recalls, the only COX-2 inhibitor available at the time of this printing is celecoxib. The dosing is 400 mg as a loading dose, followed by 200 mg every 12 hours.2 These medications are more expensive, potentially more toxic, and not necessarily superior in efficacy to less expensive, nonselective NSAIDs.

TABLE 47.1 Common Medications Used to Treat Dysmenorrhea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hormonal Therapies

If the patient wishes contraception or the pain is severe and not responsive to NSAIDs, oral contraceptives can be tried. The maximal effect may not become apparent for several months.

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) inhibit ovulation and lead to an atrophic decidualized endometrium, resulting in decreased menstrual flow and prostaglandin and leukotriene release.

OCPs are also useful to treat endometriosis because they decrease endometrial proliferation and thereby decrease total local prostaglandin and leukotriene production. A 2009 Cochrane review of randomized clinical trials concluded that OCPs provide pain relief compared to placebo for primary dysmenorrhea, with low dose pills (35 µg or less) being most effective.10 No significant differences were found between different pill formulations with respect to progestin content, but the studies were limited. When assessing other combined hormonal contraceptive methods, the vaginal ring appears to be better than the transdermal patch for dysmenorrhea.2,5 If cyclic hormonal contraception is ineffective, continuous combination hormonal therapy can be tried.1,5,9 Extended cycling may be particularly helpful. Several extended cycling OCP formulations are commercially available, and continuous therapy with the vaginal ring appears to be more effective than the transdermal patch.5.

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods have also been effective for both primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. Injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera), the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG IUS), and the subdermal progestin rod have all been shown to improve symptoms of dysmenorrhea, while Depo-Provera and the LNG IUS have been shown to be effective for endometriosis.5,8

Other Hormonal Modalities

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists with utilization of add-back therapy to prevent side effects related to hypoestrogenic state (including bone loss) have been tried in severe cases of endometriosis unresponsive to other modalities. Caution should be used in patients younger than 16 years because of concerns about compromised bone density accrual.9

Other Nonhormonal Modalities

Nonhormonal modalities with possible benefit include vitamin B1 and magnesium supplements.11 Other dietary regimens or

supplements could not be recommended based on the 2009 Cochrane review. Transcutaneous nerve stimulation12 and acupuncture13 require further study.

supplements could not be recommended based on the 2009 Cochrane review. Transcutaneous nerve stimulation12 and acupuncture13 require further study.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree