2 Ductal and Lobular Proliferations: Preinvasive Breast Disease

Introduction

The environmental and biologic factors involved in the development of epithelial proliferations of the breast and invasive breast carcinoma have been studied extensively. Despite this effort, a unified explanation of the relationship between preinvasive breast disease and invasive carcinoma remains, at best, partially answered. One hypothesis of breast cancer development holds that a sequential progression of proliferative changes places the breast at progressively increased risk for invasive carcinoma. Application of specific diagnostic criteria ensures correct categorization of these proliferative changes. Interaction between pathologists and clinicians in breast multidisciplinary conferences results in clinical-radiographic-pathologic correlation, and this should be a gold standard for the care of patients with breast disease. Although the concept of a linear model of progression is an attractive one, it is not true for all cases. In some patients, proliferative lesions appear to stabilize or even regress, and in other patients invasive carcinoma is the first indication of disease. Fortunately, however, the latter scenario is less common, and in general the progression through the preinvasive stages of breast disease is linear and continues slowly over many years, providing ample time to make a diagnosis and treat the patient.1

Epithelial proliferative diseases such as atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) are lesions of interest to pathologists, since they need to be differentiated from each other and diagnosed accurately. Clinicians have an interest because they have to manage and follow up lesions that are benign but that increase the risk for breast cancer. Although patients may not have a sophisticated understanding of all the clinical implications, they have to make decisions about therapy and rely on advice from their physicians. Finally, these preinvasive diseases are of great interest to researchers as targets for reducing the incidence of breast cancer. All concerned parties can agree that the classification of breast disease should correlate with clinical outcome and their treatment tailored accordingly. Risk is categorized as relative risk and absolute risk. Relative risk is used when comparisons are made between two groups. Thus, when it is stated that DCIS has a relative risk of 10, the comparison is assumed to be the general population (women), which has its own risk of disease. This point can by illustrated by a woman with a baseline risk of 5 in 100. The addition of DCIS would give her an added relative risk of 10. Thus, her risk of invasive carcinoma increases to 50 in 100 and does not refer in any way to risk of death from this disease.2

Absolute risk, on the other hand, identifies the risk of an individual or group of individuals to develop cancer over a unit of time (expressed as percent), independent of risks associated with other populations.3 In discussions of proliferative breast disease, it is customary to refer to the relative risk.2

The two patterns of advanced in situ proliferative lesions in the human female breast are ductal and lobular patterns. DCIS and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) were recognized as being associated with invasive carcinoma 50 years ago. Although the histologic patterns of proliferative diseases are amazingly diverse, their clinical presentation is often the same (i.e., mammographically detected calcifications).4

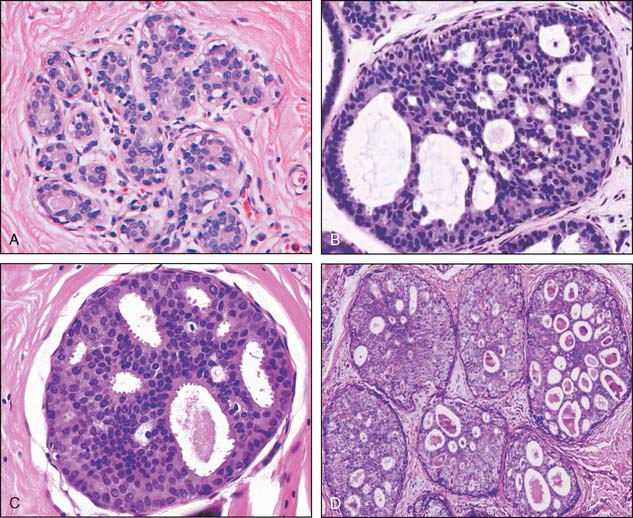

Ductal proliferations have been divided into three groups based on histologic criteria, and these have been associated with differences in prognosis. These are ductal carcinoma in situ, ductal hyperplasia of the usual type, and atypical ductal hyperplasia (Fig. 2-1).

Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

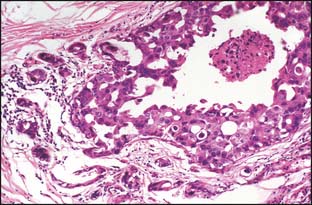

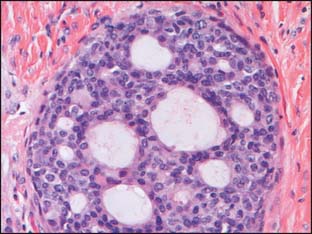

DCIS is a cytologically malignant epithelial cell proliferation that is confined within the breast epithelial structures and does not cross the basement membrane, as does invasive carcinoma.5 The distinction between DCIS and invasive carcinoma is made through histologic examination of standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained sections and in some cases with the adjunctive use of immunohistochemical stains for delineating the myoepithelial layer that invests all the breast epithelial structures (but is absent or breached in invasive carcinoma). The ideal marker for myoepithelial cells is p63 because it stains the nuclei. Cytoplasmic immunostains include smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, calponin, and muscle-specific actin (MSA), which is less specific since myofibroblasts can also be stained.

DCIS is common and has been reported in 25% of screen-detected breast carcinoma. It may arise in any location throughout either breast.6 DCIS does not always progress to invasive carcinoma.

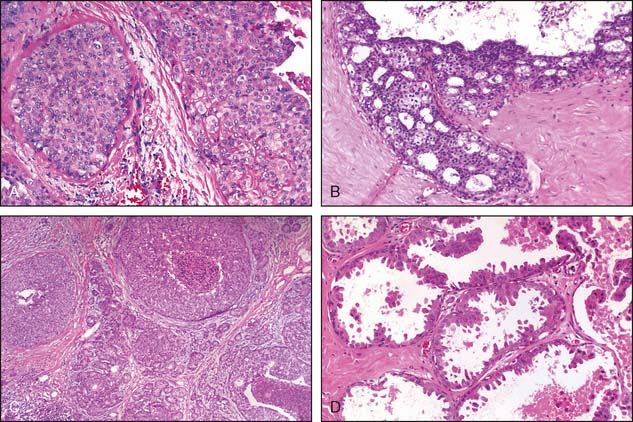

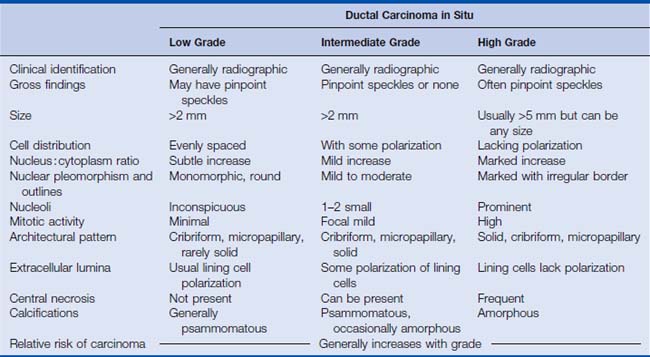

Many classification schemes have been proposed for DCIS. The commonly used ones are three-tiered, based on architectural features, the presence or absence of central necrosis, and nuclear characteristics.5 In current practice, the nuclear grade is emphasized because it is a more consistent finding compared with architectural features, which can be multiple within one patient. The nuclear grade is reported as high, intermediate, or low. Additional features that correlate with outcome include size, margin status, and the presence or absence of necrosis.5,7,8 The nuclear grade has been associated with significant prognostic differences, and in the event that more than one grade is present, the disease is classified based on the highest grade seen (Fig. 2-2). The surgical report therefore should include the nuclear grade, the presence of any necrosis, the architectural type, the size of the DCIS, the status of the margin, and the presence and location of calcifications.7

The histologic patterns of DCIS are varied, and most cases include a combination of several of the patterns. These include cribriform, solid, papillary, micropapillary, apocrine, and comedo types (see Fig. 2-3). Although additional patterns have been described, they are not common and do not convey prognostic significance. Because of the variable nature of the architectural pattern expression within the breast and the frequent overlap within these patterns, they are no longer used as the primary means of classification.5,7,8 It is important to note that central necrosis can be present in intermediate- and high-grade lesions. The term “comedo necrosis” is applied only to high-grade disease.9

High-Grade DCIS

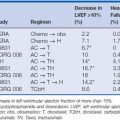

High-grade DCIS contains large neoplastic cells with markedly pleomorphic, poorly polarized nuclei with irregular contours and a coarse, clumped chromatin with prominent nucleoli (see Fig. 2-2). Mitotic figures and central necrosis are frequently present, but are not necessary for the diagnosis. Severe anaplasia of even a single layer of duct lining cells can be sufficient for a diagnosis of high-grade DCIS. High-grade DCIS is often associated with extension into the lobules, periductal desmoplasia and an inflammatory response. Although these lesions are typically larger than 5 mm, with the appropriate histologic features, the diagnosis can be rendered on lesions of any size, even less than 1 mm, particularly in needle core biopsies8 (Table 2-1).

Low-Grade DCIS

Low-grade DCIS is composed of uniform small cells that can grow in solid/cribriform, micropapillary, or arcade patterns. The cells are characterized by nuclear uniformity, rounded nuclear contours, finely granular chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 2-4). There is frequent nuclear polarity of the cells around the secondary lumina and the basement membrane of the duct. In contrast to high-grade DCIS, mitotic activity is low. By definition, necrosis is absent. The presence of necrosis indicates a more aggressive behavior than lesions with similar cytomorphologic features, but lacking necrosis.5–8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree