Drug Therapy: Introduction

Geriatric patients are sometimes viewed as “walking chemistry sets” because they are frequently prescribed multiple drugs in complex dosage schedules. This is often the result of older people seeing multiple prescribing clinicians who do not communicate with each other and a lack of a comprehensive medication list either electronically or in hard copy. With older patients, polypharmacy is common because of the presence of multiple chronic medical conditions, the proven efficacy of an increasing number of drugs for these conditions, and practice guidelines that recommend their use. The nature of drug therapy in managing chronic disease has changed greatly. Many conditions can be better controlled, but at a cost. In many instances, however, complex drug regimens are unnecessary; they are costly and predispose to nonadherence and adverse drug reactions. Many older patients are prescribed multiple drugs, take over-the-counter drugs, and are then prescribed additional drugs to treat the side effects of medications they are already taking. This scenario can result in an upward spiral in the number of drugs being taken and commonly leads to polypharmacy.

Several important pharmacological and nonpharmacological considerations influence the safety and effectiveness of drug therapy in the geriatric population. This chapter focuses on these considerations and gives practical suggestions for prescribing drugs for older patients. Drug therapy for specific geriatric conditions is discussed in several other chapters throughout this text.

Nonpharmacological Factors Influencing Drug Therapy

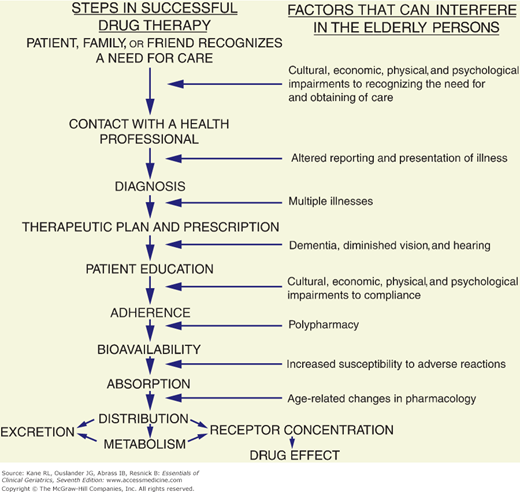

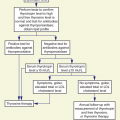

Discussions of geriatric pharmacology frequently center on age-related changes in drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Detailed reviews of these areas are provided in the Suggested Readings section at the end of the chapter. Although these changes are often of clinical importance, nonpharmacological factors can play an even greater role in the safety and effectiveness of drug therapy in the geriatric population. Several steps make drug therapy safe and effective (Fig. 14-1). Many factors can interfere with this scheme in the geriatric population, and as can be seen, most of them come into play before pharmacological considerations arise.

Effective drug therapy requires accurate diagnoses. Many older patients underreport symptoms; patient complaints may be vague and multiple. Symptoms of physical diseases frequently overlap with symptoms of psychological illness. To add to this complexity, many diseases present with atypical symptoms. Consequently, making the correct diagnoses and prescribing the appropriate drugs are often difficult tasks in the geriatric population.

Health-care professionals tend to treat symptoms with drugs rather than to evaluate the symptoms thoroughly. Because older patients often have multiple problems and complaints and consult several health-care professionals, they can readily end up with prescriptions for several drugs. Moreover, older patients or their family members sometimes exert pressure on health-care professionals to prescribe medication, thus adding to the tendency for polypharmacy. This pressure is intensified by direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs.

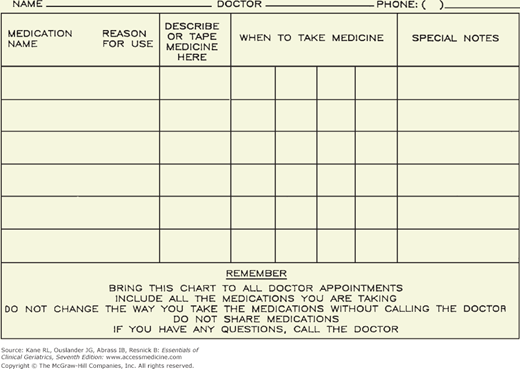

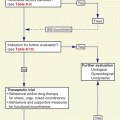

Older patients typically see many different clinicians, each of whom may prescribe medications. Frequently, neither the patients nor the health-care providers have a clear picture of the total drug regimen. New patients undergoing initial geriatric assessment should be asked to empty their medicine cabinets and to bring all bottles to their first appointments. Simple medication records, such as the one shown in Figure 14-2, carried by the patient and maintained as an integral part of the overall medical record, may help to eliminate some of the polypharmacy and nonadeherence common in the geriatric population. Such records should be updated at each patient visit. Drug regimens should be simplified whenever possible, and patients should be instructed to discard old medications. Incorporation of medication lists into electronic medical records with medication adjudication at each visit can be very helpful in maintaining an accurate medication list, reducing polypharmacy, and improving adherence. A good principle is to consider each time a new drug is added if one can be discontinued.

Adherence plays a central role in the success of drug therapy in all age groups (see Fig. 14-1). In addition to the tendency for polypharmacy and complex dosage schedules, older patients face other potential barriers to adherence. The chronic nature of illness in the geriatric population can play a role in nonadherence. The consequences of these illnesses are often delayed (as opposed to the more dramatic effects of acute illnesses), and chronic illnesses necessitate ongoing prophylactic or suppressive rather than relatively short and time-limited courses of therapy. Adherence tends to be poor for these types of drug regimens. Diminished hearing, impaired vision, poor literacy, and poor short-term memory can interfere with patient education and adherence. Individuals with mild cognitive impairment may be at particular risk for nonadherence to medication regimens (Campbell et al., 2012). Problems with transportation can make getting to a pharmacy difficult. Outpatient prescriptions are now covered by Medicare to some extent, but many older persons still have to pay for some of the costs of their drugs from a limited income. Even if the older person gets to the pharmacy, can afford the prescription, understands the instructions, and remembers when to take it, the use of childproof bottles and tamper-resistant packaging may hinder adherence in those with arthritic or weak hands.

Several strategies can improve adherence in the geriatric population (Table 14–1). As few drugs as possible should be prescribed, and the dosage schedule should be as simple as possible. All drugs should be given on the same dosage schedules whenever possible, and the administration should correspond to a daily routine in order to enhance the consistency of taking the drugs and adherence. For many drugs, once-daily dosing is available and should be prescribed when clinically appropriate. Relatives or other caregivers should be instructed in the drug regimen, and they, as well as others (eg, home health aides and pharmacists), should be enlisted to help the older patient comply. Specially designed pill dispensers and frequent human reminders can be useful. Geriatric patients and their health-care providers should keep an updated record of the drug regimen (see Fig. 14-2). For older patients who are hospitalized, medication adjudication and education should be performed at the time of discharge, because posthospital medication discrepancies are common in the older population and can have serious consequences (Coleman et al., 2005). Patients and families need to be carefully instructed on which medications have been discontinued and where dosages have been changed. Medication misuse can result, in avoidable emergency room visits. A handful of medications (warfarin, insulin, oral hypoglycemic and oral antiplatelet agents, and digoxin) account for a substantial portion of these visits (Budnitz et al., 2007; Budnitz et al., 2011). Medications should be brought to appointments, and patients and families should show all medications to their physicians, particularly on initial visits to new primary care physicians or at a consultation with a specialist. Health-care professionals should regularly inquire about other medications being taken (prescribed by other physicians or purchased over the counter) and review their patients’ knowledge of and compliance with the drug regimen.

1. Make drug regimens and instructions as simple as possible a. Use the same dosage schedule for all drugs whenever feasible (eg, once or twice per day) b. Time the doses in conjunction with a daily routine 2. Instruct relatives and caregivers on the drug regimen 3. Enlist others (eg, home health aides, pharmacists) to help ensure compliance 4. Make sure the older patient can get to a pharmacist (or vice versa), can afford the prescriptions, and can open the container 5. Use aids (such as special pillboxes and drug calendars) whenever appropriate 6. Perform careful medication adjudication and patient/family education at the time of every hospital discharge 7. Keep updated medication records (see Fig. 14-2) and review them at each visit 8. Review knowledge of and compliance with drug regimens regularly |

Adverse Drug Reactions and Interactions

Primum non nocere (“first, do no harm”), a watchword phrase in the practice of medicine, is nowhere more applicable than when drugs are being prescribed for the geriatric population. Concerns are frequently heard about inappropriate prescribing of medications with serious side effects in older people. Numerous studies over the last three decades have described the frequency of “inappropriate” drug therapy in a variety of settings. For example, a recent study of over 200,000 inpatient surgical admissions in patients age 65 and older found that one-quarter had received a potentially inappropriate medication (Finlayson et al., 2011). The American Geriatrics Society has recently completed a comprehensive review and updated the Beers Criteria, which detail potentially inappropriate medications for older adults as well as drug–drug and drug–disease interactions that should be avoided. Readers are referred to this resource for information on specific drugs to assist in preventing adverse drug reactions and interactions (American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel, 2012; also available at http://www.americangeriatrics.org/health_care_professionals/clinical_practice/clinical_guidelines_recommendations/2012).

Adverse drug reactions are the most common form of iatrogenic illness (see Chapter 5). The incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients increases from approximately 10% in those between 40 and 50 years of age to 25% in those older than age 80 (Lazarou, Pomeranz, and Corey, 1998). They account for between 3% and 10% of hospital admissions of older patients each year and result in several billion dollars in yearly health-care expenditures. Many drugs can produce distressing, and sometimes disabling or life-threatening, adverse reactions (Table 14–2). Psychotropic drugs, all drugs with substantial anticholinergic activity, and cardiovascular agents are common causes of serious adverse reactions in the geriatric population. In part, this is because of the narrow therapeutic-to-toxic ratio of many of these drugs and the sensitivity of the aging brain to anticholinergic drugs. In some instances, age-related changes in pharmacology, such as diminished renal excretion and prolonged duration of action, predispose to adverse reactions. Some side effects can have a therapeutic benefit and may be key factors in drug selection (see below).

Drug | Common adverse reactions |

|---|---|

Analgesics (see Chap. 10) | |

Anti-inflammatory agents, aspirin | Gastric irritation and ulcers Chronic blood loss |

Narcotics | Constipation |

Antimicrobials | |

Aminoglycosides | Renal failure Hearing loss |

Other antimicrobials | Diarrhea |

Antiparkinsonian Drugs (see Chap. 10) | |

Dopaminergic agents | Nausea Delirium Hallucinations Postural hypotension |

Anticholinergics | Dry mouth Constipation Urinary retention Delirium |

Cardiovascular Drugs (see Chap. 11) | |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors | Cough Impaired renal function |

Antiarrhythmics | Pulmonary toxicity, bradycardia, hypotension (amiodarone) Diarrhea (quinidine) Urinary retention (disopyramide) |

Anticoagulants | Bleeding complications |

Antihypertensives | Hypotension |

Calcium channel blockers | Decreased myocardial contractility Edema Constipation |

Diuretics | Dehydration Hyponatremia Hypokalemia Incontinence |

Digoxin | Arrhythmias Nausea Anorexia |

Nitrates | Hypotension |

Statins | Myopathy, hepatotoxicity |

Hypoglycemic Agents | |

Insulin | Hypoglycemia |

Oral agents | Edema (glitazones) Diarrhea (metformin) |

Lower Urinary Tract Drugs (see Chap. 8) | |

Antimuscarinics | Dry mouth, eyes |

Oral agents | Constipation Esophageal reflux |

α-Blockers | Postural hypotension |

Psychotropic Drugs (see Tables 14-8 and 14-9) | |

Antidepressants | (See Chapter 7) |

Antipsychotics | Death Sedation Hypotension Extrapyramidal movement disorders Weight gain |

Cholinesterase inhibitors | Falls Syncope Nausea, diarrhea |

Lithium | Weakness Tremor Nausea Delirium |

Sedative and hypnotic agents | Excessive sedation Delirium Gait disturbances and falls |

Others | |

Alendronate, risedronate | Esophageal ulceration |

Aminophylline, theophylline | Gastric irritation Tachyarrhythmias |

Carbamazepine | Anemia Hyponatremia Neutropenia |

Because symptoms can be nonspecific or may mimic other illnesses, adverse drug reactions may be ignored or unrecognized. Patients and family members should be educated to recognize and report common and potentially serious adverse reactions. In some instances, another drug is prescribed to treat these symptoms, thus contributing to polypharmacy and increasing the likelihood of an adverse drug interaction. The problem of polypharmacy is exacerbated by visits to multiple physicians, who may prescribe still more drugs and the use of multiple pharmacies. Medication records kept by the patient (see Fig. 14-2), the physician’s medical record, and the increasing use of electronic medical records should help to prevent unnecessary polypharmacy when many physicians are involved. Several drugs commonly prescribed for the geriatric population can interact with adverse consequences (American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel, 2012; Hines and Murphy, 2011). Table 14–3 lists some of the more common potential adverse drug–drug interactions. The more common types are drug displacement from protein-binding sites by other highly protein-bound drugs, induction or suppression of the metabolism of other drugs, and additive effects of different drugs on blood pressure and mental function (mood, level of consciousness, etc.). Interactions among drugs metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system in the liver are especially common (see Wilkinson, 2005, for a review). Because many older patients are treated with warfarin for atrial fibrillation or venous thrombosis, clinicians must be aware of the many potential drug–drug and drug–nutrient interactions with this medication (Holbrook et al., 2005). In addition to the potential to interact with other drugs, several drugs can interact adversely with underlying medical conditions in the geriatric population, creating “drug–patient” interactions (American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel, 2012; see Table 14–4 for examples). A good example of this problem is the increased risk of hospitalization for congestive heart failure (CHF) among older patients taking diuretics who are told to take a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (Heerdink et al., 1998).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree