Introduction

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a failure of haemostatic homeostasis (Figure 30.1). The haemostatic system comprises five components: the coagulation cascade, the fibrinolytic cascade, platelets, the natural anticoagulant pathway and vascular endothelial cells. It is a complex system which normally maintains blood fluidity when blood is confined within the intravascular vessels, but is able to trigger rapid and localized coagulation if vascular integrity is breached. The intravascular space usually contains no exposed tissue factor but all cells outside the vascular system express tissue factor in their cell membranes which initiates coagulation through the extrinsic pathway. In DIC there is unregulated and uncontrolled activation of the coagulation cascade and platelets resulting in blockage of the microvascular system of critical organs. Simultaneously, there is activation of the fibrinolytic cascade generating plasmin and consequently fibrin and fibrinogen degradation, together with depletion of components of the natural anticoagulant pathway which contribute to the systemic bleeding diathesis.1, 2 Hence the paradox of DIC is that the clinical manifestations are of bleeding while the patient suffers serious morbidity and mortality due to organ damage due to microvascular thrombosis. DIC usually has an acute onset with bleeding manifestations dominating the clinical picture; however, a chronic form can occur, the manifestations of which are very different, usually with presentation as thrombosis, and the management of this form of condition likewise differs.

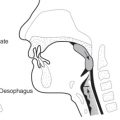

Figure 30.1 Mechanism of microvascular thrombosis and bleeding in DIC. Broken lines indicate inhibition.

Pathophysiology

DIC is a pathophysiological syndrome characterized by clinical manifestations of generalized bleeding together with laboratory features of severe coagulopathy. It is not a discrete pathological entity but a final common pathway for a variety of triggers and precipitating factors and can be initiated by a number of different mechanisms (Table 30.1). DIC is characterized by great variation both between patients and within the same patient over time. It is a dynamic condition that will progress if untreated but can rapidly improve if appropriate treatment of the underlying cause and support haemostatic factors is given. Consequently, it has been difficult to perform adequate randomized controlled trials in the management and treatment of DIC, although there have been several recent advances in its early diagnosis and treatment.3

Table 30.1 Mechanisms and precipitating factors in DIC.

| Mechanism | Example |

| Coagulation cascade activation | Tissue factor exposure in trauma and extensive surgery |

| Fibrinolytic cascade activation | Plasminogen activators liberated in acute promyelocytic leukaemia |

| Intravascular platelet aggregation | Haemolytic uraemic syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Endothelial cell activation | Gram-negative sepsis, malignancy |

| Direct proteolytic cleavage of haemostatic proteins | Pancreatitis, snake venoms |

The primary triggers of DIC in the elderly are sepsis and malignancy, particularly disseminated malignancy. Other causes include massive trauma and major surgery, and ABO-incompatible blood transfusions and snake bites are rarer but recognized causes. DIC may be precipitated by activation of the coagulation cascade following tissue factor exposure, for example, as in massive trauma and major surgery; activation of the fibrinolytic cascade, for example, the liberation of plasminogen activators by leukaemic blasts in acute promyelocytic leukaemia or carcinoma of the prostrate; intravascular platelet activation, for example, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia; and by endotoxins in Gram-negative sepsis and meningococcal septicaemia or by direct proteolytic cleavage of circulating haemostatic proteins, as occurs in pancreatitis and with some snake venoms (Table 30.1). In addition to uncontrolled activation of the platelets and the coagulation cascade, there is depletion of the proteins of the natural anticoagulant pathway. Depletion of these further enhances the microvascular thrombosis and also leads to activation of the complement system, resulting in an inflammatory response and generation of vasoactive peptides, such as bradykinin. DIC also provokes a poorly characterized neuroendocrine response involving elevated catecholamines and glucocorticoids.4

Clinically, DIC manifests as simultaneous bleeding and microvascular thrombosis leading to multiple organ dysfunction including renal failure and adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and is often associated with fever, hypotension, acidosis, hypoxia and proteinuria. While bleeding is the most obvious and commonly recognized manifestation, death by exsanguinations is rare due to the appropriate use of blood and platelet transfusions. The usual cause of death in DIC is multiorgan failure as a consequence of the microvascular thrombosis, which is not so clinically obvious. Treatment of multiorgan failure, which is a consequence of anoxia and ischaemic necrosis of vital organs, is far more difficult to treat satisfactorily.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree