Sean D. Christie, Richard Cowie

Disorders of the Spinal Cord and Nerve Roots

Most pathologic processes that affect the spinal cord in older adults are related to degenerative diseases of the spinal column or to insufficiency of the cord’s blood supply. Even so, old age does not exclude many of the disorders that are more commonly seen in other age groups. In most patients, a definitive diagnosis can be made clinically by taking a directed history and performing a careful examination.

Neurologic assessment of an older adult is sometimes made difficult by failure to obtain a clear history or by the presence of common comorbidities that can challenge interpretation of symptoms and signs. For example, muscle atrophy may mimic neurologic weakness and diminish deep tendon reflexes. Nonetheless, an analysis of how a neurologic disorder has developed and the pattern of neurologic signs should provide a guide to the location of the lesion along the neural axis. A lesion can usually be localized in the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, or sacral segments before specialized neuroradiologic investigation.

Cervical Radiculopathy and Myelopathy

General Issues

The neuroradiologic sequelae of degenerative disease of the cervical spine were established in the 1950s.1 The degenerative changes of cervical spondylosis begin with desiccation and fragmentation of the intervertebral discs. As annular elasticity and nuclear hydration become reduced with age, the disc height diminishes. Consequently, extremes of movement are less well tolerated, and the vertebral end plates are subjected to greater stress. Secondary osteophytic spurs then develop circumferentially around the disc, projecting posteriorly into the spinal canal as bony ridges. Parallel degeneration of the hypophyseal (facet) joints combines with spurs from the vertebral bodies to reduce the size of the spinal canal and neural foramina. In most patients, there is progressive loss of movement between vertebrae, although in some cases excessive motion between vertebrae may develop and produce a degree of subluxation. Pathologic changes in the ligamentum flavum cause lack of elasticity and a tendency to buckle, further reducing spinal canal diameter. The compressive effects of the osteophytic spurs and buckled ligamentum flavum on the spinal cord are greatest when the neck is extended.2 These changes bring about restriction of the natural motion of the spinal cord and nerve roots within the spinal canal.

Repetitive compression and obstruction of the radicular arteries supplying the cord in the neural foramina may further compromise cord function. This effect is aggravated if there is occlusive vascular disease of the proximal arteries in the neck.

Occasionally, acute rupture of a cervical disc can follow sudden twisting or flexion-extension movements of the neck and can produce spinal cord or nerve root compression.3 The same mechanism can also cause hemorrhage into the spinal cord (hematomyelia). With age, such degenerative changes increase in severity and extent. Epidemiologic studies4,5 have shown that most degenerative changes are in those who have done heavy labor.

Atomic and radiologic studies show that the neurologic sequelae of cervical spondylosis are more prevalent when the natural size of the spinal canal and neural foramina are restricted.6 When present, large osteophytic ridges and subluxation of the vertebrae aggravate the situation. The C5-C6 and C6-C7 levels are most commonly affected because these are the points of transition from the more mobile cervical spine to the relatively fixed section in the upper part of the thoracic spine.5,7

Clinically, there is generally loss of lordosis, so that the head is held flexed and downward. However, if the natural kyphosis of the thoracic spine is exaggerated, there may be a compensatory extension of the upper cervical spine to maintain forward gaze. Most patients complain of recurrent neck pain and stiffness, together with crepitus on movement. Pain radiates to the occiput, shoulders, and scapula regions.

Radiculopathy

Progressive narrowing of the neural foramina results from osteophytic ridges—the bulging or herniated intervertebral discs and hypertrophy of the facet joints. This produces compression and restriction of movement of the nerve root.

Pain radiates down the arm in the distribution of the nerve root(s) with a deep, boring quality, aggravated by activities such as lifting and reaching. The pain is generally accompanied by paresthesias and some sensory loss in the affected dermatomes. In some patients, sensory symptoms predominate. Muscular weakness is generally mild, but occasionally wasting can occur. The appropriate reflexes are lost.7

Cervical Myelopathy

Cervical spondylosis is the most frequent cause of chronic cord compression in older adults. The clinical spectrum is wide, depending on many interrelating factors and the pathogenesis of cord damage. Compression leads to atrophy of the anterior horn cells and lateral and posterior funiculi of the cord.8 Usually, the onset of symptoms and signs is insidious, and a clinical history can extend for many months or years before help is sought. Most frequently, there is a mixed picture of lower motor neuron features in the arms, together with long tract signs below.9

In the upper limbs, complaints of numb clumsy hands with weakness and loss of dexterity are common. Muscle wasting follows segmental anterior horn cell damage, affecting proximal muscles when compression is high in the cervical spine or more distally when compression is lower. The tendon reflexes in the arms are usually lost at the pathologic level of the cord and are exaggerated below. An inverted radial reflex occurs when the site of compression is above the fifth cervical segment, which has been shown to be the most common in older adults.10 In contrast, there is commonly marked lower limb spasticity where the patient complains of a heavy leaden weakness and a tendency to drag the limb. Some degree of ataxia may be present due to reduction of vibration and joint position sense caused by damage to the posterior columns. Many patients complain of paresthesias and intermittent numbness in the upper and lower limbs.

Occasionally, symptoms may arise abruptly because of severe trauma or sudden extension of the neck in patients with cervical stenosis, such as after a fall. In this situation, a central cord syndrome is common. This scenario produces marked weakness of the upper limbs caused by anterior horn cell damage and a mild spastic weakness of the lower limbs because the peripheral regions of the cord are relatively spared. Frequently, this syndrome is accompanied by allodynia in the upper extremities, particularly the hands, and a suspended sensory loss because the centrally located decussating fibers of the spinothalamic tract are damaged. Very rarely, a hemicord pathology can produce a Brown-Séquard syndrome.

These neurologic disorders can be associated with vertebrobasilar insufficiency, in which symptoms are typically related to rotation and extension of the neck. Because the clinical presentation of spondylotic myelopathy varies, it must be distinguished from other conditions with similar symptoms and signs, including multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), cerebrovascular disease, cord tumor or syrinx, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, and peripheral neuropathies.

Diagnostic Procedures

Plain radiographs of the cervical spine reveal narrowing of the intervertebral disc space, with sclerosis of adjacent cortical bone, osteophytic spurs, malalignment, and canal diameter. Patients with cervical myelopathy have an average minimal anteroposterior (AP) canal diameter of 11.8 mm,11 and values less than 10 mm were likely to be associated with myelopathy.12 An AP canal diameter more than 16 mm rarely produces myelopathic changes.13 Secondary anterior and posterior osteophytes are demonstrated in Figure 67-1, together with an indication of the size of the spinal canal. Oblique radiographs allow visualization of the neural foramina. However, several authors14–16 have shown that degenerative changes increase in frequency with age, and that 70% to 90% of those older than 65 years have radiologic abnormalities. In consequence, there is poor correlation between symptomatic and asymptomatic groups and the structural changes revealed on plain radiographs, with problems of sensitivity and especially, of specificity. Rarely, then, do plain radiographs alone dictate therapy.

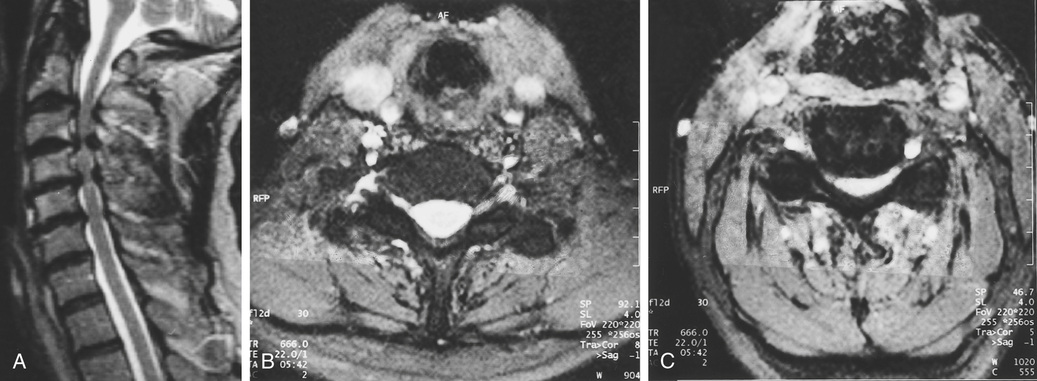

When the clinical state suggests segmental cord or root compression and surgery is contemplated, specialized neuroradiologic studies are required. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which has largely replaced myelography, reveals degeneration of the intervertebral discs, size of osteophytes, and presence and degree of cord compression (Figure 67-2). MRI also reveals intrinsic cord abnormalities (e.g., syringomyelia, demyelination; see Figure 67-2) and is helpful to exclude other pathologies, including a Chiari malformation and spinal cord tumor. Findings on MRI that correlate with poor functional outcomes include T2 hyperintensities within the spinal cord parenchyma and spinal cord atrophy of a transverse area smaller than 45 mm2.17 Unfortunately, MRI scans poorly visualize calcified structures such as osteophytes, and calcified ligaments and discs. Thus, computed tomography (CT) is often performed.

CT18,19 reveals the size and shape of the vertebral canals and presence of extensive ligamentous calcification, but it cannot give details of vertebral displacements, disc protrusions, and corrugation of the bulging longitudinal ligament unless an intrathecal contrast medium has been injected. Myelography is now performed only when MRI is contraindicated, such as in a patient with an implanted pacemaker or neuromodulatory device or in the presence of cerebral aneurysm clips made from materials other than titanium or titanium alloy.20

Management

Cervical radiculopathy and associated neck pain improve without surgical intervention in over 90% of cases.21 Reduction in symptom severity can be achieved through a multimodality approach. This may include analgesia with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, and neuropathic agents such as gabapentin and its derivatives. Physical therapy, including traction, may diminish the severity of symptoms.22

Surgical intervention for cervical radiculopathy aims to eliminate the compression on the affected nerve root. The surgical options include anterior and posterior approaches, depending on the location and source of the compression; each carries a good prognosis for neurologic recovery,23–25 although recovery of muscle wasting is rarely satisfactory. Surgery should be considered when the patient fails to respond to nonsurgical intervention or when neurologic deficits worsen or new deficits arise. Consideration should also be given to patients whose symptoms are so severe they cannot partake in routine daily activities. Finally, the patient must be able to withstand the stress of surgery, including the general anesthetic.

The natural history of myelopathy complicating cervical spondylosis is variable and unpredictable. Many patients run a chronic course characterized by episodes of deterioration separated by periods of stability, whereas others have a more progressive course.9,26 Most older adults with cervical myelopathy will not need surgical intervention. Often, a nonoperative approach may hasten progression and alleviate symptoms. Noninvasive strategies include rigid collars to restrict small repetitive trauma, NSAIDs, and education regarding avoidance of potential harmful activities.

Surgical treatment is indicated when the myelopathy interferes with daily activities, there is a short progressive history, or there is radiologic evidence of severe cord compression or instability. Anterior decompression of disc and osteophytic spurs is usually carried out when up to three intervertebral levels are affected. Posterior decompression, including laminectomy and laminoplasty, is indicated for more widespread stenosis. In general, the prime objective of surgery has been to halt the decline in neurologic function before further damage to the cord has occurred. However, studies have suggested that there may be a more reliable improvement in neurologic function than previously appreciated.27

Prognosis following surgery depends on multiple factors, including duration of symptoms and severity at presentation. A longer duration of symptoms has been shown to diminish functional outcomes following decompression.28 Likewise, an increasing severity of symptoms at presentation29 is a poor prognostic factor. Concomitant fusion along with decompression limits motion at the surgical site. This may limit vascular insufficiency associated with movement and prevent further deterioration.9

Cord Compression

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Neck pain and stiffness are common complaints in patients with progressive rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Radiation of pain to the occipital region and cutaneous numbness at the back of the head may occur when the upper cervical nerve roots are compressed. These symptoms may herald the development of atlantoaxial subluxation as a result of destruction of the transverse atlantal ligament by synovitis. There may be rotatory subluxation and vertical migration of the odontoid into the foramen magnum of the skull (cranial settling or basilar impression or invagination). Atlantoaxial subluxation, which occurs in approximately 33% of patients with RA, can be asymptomatic until the slip reaches 8 to 9 mm, at which point spinal cord compression begins. Once myelopathy develops, most patients deteriorate, and 50% die within 6 months. Approximately 20% of patients show subaxial subluxation on cervical radiography, often affecting several segments to produce a so-called staircase deformity of the vertebrae. Compression of the cord and myelopathy are common in this situation.

Most patients present with progressive deterioration of upper limb function, accompanied by tingling, numbness, the Lhermitte phenomenon, gait disturbance, and possibly bladder and bowel dysfunction. It is common for these symptoms to be initially attributed to severe peripheral joint disease and muscle atrophy. Abnormality of spinothalamic function, hyperreflexia and hypertonia, and extensor plantar responses help differentiate the cause from peripheral nerve lesions. Compression of the trigeminal nucleus and tract at the craniocervical junction may produce facial numbness or paresthesias. Lower cranial nerve findings (cranial nerves IX to XII) may be present with cranial settling.

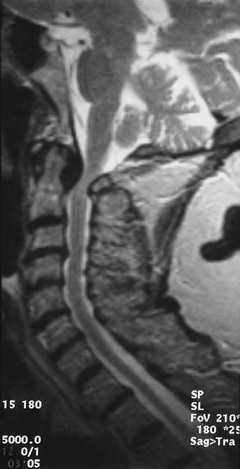

Radiologic assessment requires flexion and extension radiographs of the cervical spine. This is followed by MRI, which will reveal compression or distortion of the spinal cord (Figure 67-3).

Surgical management has to be considered when there is progressive or significant atlantoaxial subluxation or clinical evidence of increasing neurologic morbidity. Because most patients have significant medical problems, such as pulmonary fibrosis, anemia, atrophic skin, and the effects of prolonged steroid or other immunosuppressive therapy, there is significant risk from surgical intervention that needs to be reviewed with the patient and family or caregiver. For some patients, particularly those who are frail, the use of a cervical collar in lieu of surgery may be the best option to manage craniocervical instability, although tolerance of use can be limited.

The surgical approach and procedure may consist of an anterior, transoral, or posterior decompression combined with internal fixation. However, the timing of these interventions remains controversial.30

Thoracic Disc Protrusion

The central protrusion of a thoracic intervertebral disc is an unusual cause of cord compression, but one that occurs in older adults because it is associated with degeneration of the disc annulus. Russell31 has noted that 67% occur between the eighth and eleventh interspaces. Most patients present with a long history of gradually progressive myelopathy, in which sensory and motor symptoms are equally common. However, 49% of patients complain of radicular symptoms of pain and dysesthesiae. Sometimes, the onset is more rapid, leading to a flaccid paraplegia.32 The presence of a thoracic disc protrusion is generally recognized when MRI is carried out to investigate the progressive neurologic deficit. Cord compression from this source carries a poor prognosis unless surgery is performed. The results of simple decompressive laminectomy are unsatisfactory; a costotransversectomy, transpedicular, or transthoracic approach is recommended.31,33 Minimal access approaches34 are better tolerated and may lead to quicker postoperative recovery, particularly in older adults.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree