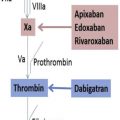

In this issue of Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America , we briefly review the history of discovery of the first anticoagulants, heparin and warfarin, and their development for clinical use. We then focus on the DOACs and the information providers need to know for the effective and safe use of these agents in clinical practice. Experts in the field provide concise information on the currently approved indications for use, including postorthopedic joint replacement venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation, and the acute and extended treatment of VTE. Information on how to monitor the anticoagulant activity of these agents when necessary is provided. Expert opinion, incorporating the limited available data, is given on the use of these agents in the perioperative setting and in populations with characteristics that would have excluded them in large numbers from the major clinical studies, such as renal insufficiency, obesity, and age. Information about the reversal agents for the DOACs is provided. The lack of reversal agents has been a major concern for both patients and clinicians and has been an obstacle for use for many patients. Lack of reversal agents should no longer be of concern as a specific reversal agent for dabigatran is now approved for use in the United States, Canada, and Europe, with the approval of a reversal agent for the Xa inhibitors expected by the time this issue of Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America is printed. Finally, regulatory issues surrounding VTE treatment and anticoagulant use are discussed with their impact on clinical practice.

The anticoagulant field is evolving rapidly, and there is much to learn about these new drugs. Questions such as, should target levels be used for certain populations, what are those levels, and how do they vary by indication, all need to be explored and identified. These anticoagulants are not new any longer, and although novel in their direct targeting of specific activated anticoagulant factors, they are anticoagulants. Inhibition of thrombosis is also accompanied by impaired hemostasis, although to a lesser degree than with the traditional anticoagulants. Information on new strategies with different targets that might uncouple thrombosis and hemostasis is included, although these strategies are in the early phase of development and significantly more work is needed before they are adopted in clinical practice.

Although more information on DOACs will undoubtedly be available in the future, it will build on the basics that are included in this issue of Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America . The authors and I hope that you will find this information useful and informative for clinical practice in the real world today.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree