(a) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), NOS

T-cell/histiocyte rich large B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL)

EBV + DLBCL of the “elderly”

(b) DLBCL with a predominant extranodal location

Primary mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma (PMBL)

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL)

Primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type (PCLBCL, leg type)

Primary DLBCL of CNS

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis

(c) Large-cell lymphomas of terminally differentiated B-cells

ALK positive large B-cell lymphoma

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL)

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL)

DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation

(d) B-cell neoplasms with features intermediated between DLBCL and other lymphoid tumours

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse and large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse and large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma

Aetiology

Often the aetiology remains unclear. Most of the DLBCL develop as a new disease, so called primary DLBCL, others can transform from other lymphatic neoplasia, so called secondary DLBCL. Prior exposure to agents causing DNA-damage and primary and secondary immunodeficiencies are associated with an increased risk of the development of a DLBCL. Certain chronic virus infections are associated with the occurrence of DLBCL, such as HCV, HIV and EBV. In elderly patients secondary lymphoma are more common than in younger ones. The EBV positive DLBCL in elderly patients should be classified as own entity and are associated with a worse prognosis than the EBV negative one [4].

Biology

The origins of DLBCL are not well understood. Usually, it evolves from normal B cells, but it can also result from malignant transformation of other types of malignant lymphatic neoplasia.

In general DLBCL encompasses a biologically and clinically diverse group of diseases, many of which cannot be separated from one another by well-defined and widely accepted criteria. Therefore new methods of genetic analysis are used for further characterization. DLBCL, NOS can be separate in germinal centre B-like DLBCL (GCB), activated B-like (ACB) DLBCL [5]. Lymphoma cells in the germinal centre B-cell-like subgroup resemble normal B cells in the germinal centre closely, and are generally associated with a favourable prognosis. Activated B-cell-like tumour cells are named from studies showing the constant activation of physiologic B-cell- antigen pathways. They are associated with a poorer prognosis [6]. One of the important pathways involved is the NF-κB pathway, which normally helps transforming B cells into plasma cells [7]. ACB subtype is more common in older patients, but compared to other molecular changes, which loose their prognostic importance when age was added as factor, age and ACB subtype independently contributed to poor prognosis [8].

In addition, gene expression studies found out more about cells and microscopic structures that are spreading within the malignant B- cells and form the tumour microenvironment. In particular, gene expression signatures that are linked with macrophages, T cells, and remodelling of the extracellular matrix seems to be associated with an improved prognosis and better overall survival [9]. On the other hand, the expression of genes involved in enhanced angiogenesis is associated with poorer survival [7].

Only a few genetic aberrations constituted valuable prognostic factors so far. Of these, the translocation of the MYC- oncogene has been associated with inferior survival. An additional translocation in BCL2 leads to an even worse prognosis and are named “double hit lymphomas”) [10].

With the help of the above diagnostic criteria derived from primary lymphoma tissue, one can distinguish few important subtypes: the T cell/histiocyte rich large B-cell lymphoma and the Primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type and the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DLBCL of the elderly for which data on modern genetic testing come up as well [11, 12]. Other additional subtypes of large- B-cell lymphomas that are diagnosed and treated in the same way are, such as primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, ALK + large B-cell lymphoma, plasmoblastic lymphoma and follicular Lymphoma Grade 3B. The DLBCL of the central nervous system displays great differences concerning disease biology and treatment and will thus not be discussed here.

Data on age associated differences in biology of DLBCL are still limited. Patterns of gene expression are not routinely determined in clinical practice but will gain importance. However, as new therapeutic options might help to overcome negative prognostic molecular changes, the tests will become part of routine [13].

Symptoms

DLBCL is cancer of rapid growth which can occur in any part of the body. Typical first signs of this disease are fast growing masses of lymphatic tissue. Others may present as a tumour of unknown origin, with histology revealing a lymphoma instead of a carcinoma. Age associated changes in presentation have not been reported so far. Elderly patients more often present with extranodal disease [14]. In one third of the patients systemic symptoms are present at diagnosis, such as concomitant fever (>38 °C for at least 3 consecutive days), weight loss (>10 % during the 6 months prior to diagnosis), and night sweats, called B-symptoms [15].

Examination

Examination serves (a) the diagnosis of the disease, (b) the extend of the disease and (c) the judgment of the patients fitness for treatment.

The diagnosis is based on a histological examination of a biopsy, preferable from palpable lymph nodes, when ever possible as excisional biopsy. Core needle biopsy should be restricted to cases where no other surgical access is possible, without major surgery.

The procedures to diagnose the extend of the disease are listed in the following Table 11.2. They do not differ between younger and older patients.

Table 11.2

Diagnostic procedures in patients with DLBCL

History and physical exam (including evaluation of all lymph node enlargement, recording site and size of all abnormal lymph nodes, inspection of Waldeyer’s ring, evaluation of the presence or absence of hepatosplenomegaly, inspection of the skin, and detection of palpable masses) |

Performance status according to the Eastern-Cooperative-Oncology-Group (ECOG) and geriatric assessment |

Blood tests (full blood count, Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH), liver and renal function test including creatine-clearance, uric acid, electrolytes, HIV, HBV- and HCV-, EBV-serology, CMV-serology) |

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy |

CT scan or PET/CT scan |

Lumbal puncture for liquor cytology and brain MRI in patients with high risk for ZNS- involvement or recurrence |

In patients with involvement of extranodal sites, further specific investigations might be necessary |

The stage of the disease is classified according to the Ann-Arbor-Classification, see Table 11.3. No differences in staging system between younger and older patients exist.

Stage I — Only one lymph node region is involved, only one lymph structure is involved, or only one extranodal site (IE) is involved. |

Stage II — Two or more lymph node regions or lymph node structures on the same side of the diaphragm are involved. |

Stage III — Lymph node regions or structures on both sides of the diaphragm are involved |

Stage IV — There is widespread involvement of a number of organs or tissues other than lymph node regions or structures, such as the liver, lung, or bone marrow. |

Systemic Symptoms as fever, weight loss or night sweats are also included in the staging process: “A” means these symptoms are not present and “B” means they are.

The judgment of a patients fitness for treatment includes cardic, renal and pulmonary function test. In addition a structured geriatric assessment (GA) is recommended at least for patients aged 70 years and older [18]. A screening tool is less specific but might be an approach in a busy clinic [19]. Results of GA are associated with survival in patients with malignant lymphoma [20, 21].

A geriatric assessment was better in judging the patients prognosis than physicians. Tucci et al. included patients with newly diagnoses DLBCL in a prospective cohort trial. All patients received a geriatric assessment. The treating physician was blinded for the results of the geriatric assessment when deciding on patients´ fitness for treatment. Most of the patients were considered fit for an R-CHOP regimen, others not, they received attenuated dose regimens, corticosteroids or single agent Rituximab. The geriatric assessment classified more patients as not fit for R-CHOP. The prognosis of patients classified by physicians as fit but by assessment as unfit was identical to the prognosis of those classified as unfit by the physicians and the assessment [22].

Patients’ fitness for treatment should be assessed at the time of diagnosis and after a prophase treatment (see below) [15].

Prognostic Factors

Prognostic factors predicting overall survival can be related to the disease (stage, LDH, extranodal involvement) and to the patients (age, performance-status) and the treatment, as response after treatment is a highly predictive factor for survival.

The following factors have been identified as independently associated with survival and thus are included in the International Prognostic Index (IPI) scoring system. In addition an age-adapted version (aaIPI), was established, see Tables 11.4 and 11.5 [23].

Age younger and older than 60 (0 vs. 1)a |

LDH level normal or higher than normal (0 vs. 1) |

General health status (ECOG performance status score 0–1 or 2 and greater) (0 vs. 1) |

Stage I – II or III – IV disease (0 vs. 1) |

Involvement of more than one extranodal site present or not (0 vs. 1)a |

Risk group | Number of risk factors in IPI | Number of risk factors in aaIPI | 5 years survival rate (all patients) | 5 years survival rate (patients >60 years) | 3 years survival rate (patients aged >60 years from RICOVER-trial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Low | 0–1 | 0 | 73 | 56 | 88 |

Low-intermediate | 2 | 1 | 51 | 44 | 79 |

High-intermediate | 3 | 2 | 43 | 37 | 68 |

High | 4–5 | 3 | 26 | 21 | 58 |

As the prognostic classification according to the IPI and aaIPI was established based on data, prior to the inclusion of Rituximab into the treatment, the scores were re-evaluated based on data of patients treated with Rituximab containing regimes. The data are reported in Table 11.6. Sehn et al. suggest based on their data analysing population based data, to use three instead of four prognostic categories: very good, good, and poor; and renamed the IPI to a revised IPI [24]. The former distribution had separated only two different prognostic groups, factors 0–2 and factors 3–4. The median age of the included patients was 61 years. Ziepert et al. analysed treatment results of clinical trials including patients aged 60 years and older with DLBCL. They confirmed the prognostic value of the aaIPI regarding PFS, EFS and OS [25]. As age above 60 years is a factor of IPI, older patients per se can not be in a very good risk group.

Risk group | No of IPI factors | 4 years OS |

|---|---|---|

Very good | 0 | 94 |

Good | 1.2 | 79 |

Poor | 3–5 | 55 |

Treatment

None or delayed treatment leads to death within weeks to few months. Treatment decision should into account the stage of the disease and the IPI in addition to patients´ fitness. Chemotherapy with CHOP is the backbone of treatment in patients with DLBCL. It was established in 1976. The initial trial included patients with a median age of 53 years [26].

As the IPI identified age, below and above the age of 60 years, as major prognostic factor, as treatment toxicity increases with age, and as in younger patients, strategies to increase dose of chemotherapy, with the hope of increased remission and survival rate, trials often used age limit of 60 years as definition of elderly patients.

1st line Treatment for Fit Patients Aged 60–80 Years

The addition of Rituximab, a chimeric CD 20 antibody, added to CHOP improved treatment results substantially, as demonstrated in different trials. Coiffer et al. were the first to show that the addition Rituximab was able to improve response rate, event-free and overall survival in patient aged 60–80 years [27]. Maintenance therapy with Rituximab following the R-CHOP regime seemed demonstrated no further improvement in outcome [28]. The RICOVER-60 trial compared different dosing intervals and numbers of therapy cycles, R-CHOP given every 14 days (R-CHOP-14) proved most effective in maximizing event free and overall survival for the same patient group [29]. The shorter interval includes obligatory application of G-CSF as part of the dose-dense protocol.

However, there is an ongoing discussion whether this data apply to patients prognostic risk groups in the age adjusted IPI. Furthermore, the application of R-CHOP-14 in this age group resulted in more frequent grade 3 and 4 neutropenia and increased number of transfusions [30, 31]. Table 11.7 summarizes the results of 1st line regimens containing R-CHOP as a treatment arm.

Table 11.7

RCTs on 1st line treatment of patients with DLBCL aged 60 years and older

1st author and year | Treatment | N = /Age group/median | % of patients ECOG-PS-2 | % of patients aged 80+ | Primary endpoint results | Overall survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coffier et al. NEJM (2002) [27] | 8 × CHOP-21 vs. 8 × R-CHOP-21 | 339/60–80/69 | 20 | 0 | EFS: 2 years-EFS 38 vs. 57 %; p < 0.01 | 2 years-OS 57 vs. 70 %; p < 0.01 |

Pfreundschuh et al. Lancet Oncol (2008) [29] | (1) CHOP-14 vs. R-CHOP-14 + (2) 6 vs. 8 cycles | 1,222/61–80/68 | 14 | 0 | EFS: 3 years-EFS 47.2 vs. 53.0 % for 6 vs. 8 CHOP and 66.5 vs. 63.1 % for 6 vs. 8 R-CHOP | OS: 3 years-OS 67.7 vs. 66.0 % for 6 vs. 8 CHOP and 78.1 vs. 72.5 % for 6 vs. 8 R-CHOP |

Habermann et al. JCO (2006) [28] | (1) CHOP 21 vs. R-CHOP + (2) NIL vs. R Maintenance | 632/60–92/69 | 15 | 8 | FFS: 3 years-FFS 46 vs. 53 %; p = 0.04 | OS: 3 years-OS 58 vs. 67 %; |

Delarue et al. Lancet Oncol (2013) [30] | 8 × R-CHOP-21 vs. 8 × R-CHOP-14 | 602/60–80/70 | 22 | 0 | EFS: 3 years-EFS 56 vs. 60 % p = 0.7614 (NS) | OS: 3 years-OS 72 vs. 69 % (NS) |

Cunningham et al. Lancet (2013) [31] | 8 × R-CHOP-21 vs. 8 × R-CHOP-14 | 1,080/19–88/61 | 13 | n.r. | OS: 2-years-OS 80.8 vs. 82.7; p = NS | See primary end point |

All in all 6–8 cycles of R-CHOP-14 or R-CHOP-21 should be the current standard of care for fit patients and according to these pivotal trials for patients aged younger than 80 years.

Prior to the start of the R-CHOP regimen a prophase treatment is recommended, consisting of a single intravenous injection of vinristin 1 mg day 1 and oral prednisolone for 7 days. Besides not being tested in a randomized fashion, toxicity in the 1st cycle reduced substantially [15].

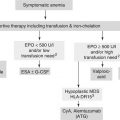

1st Line Treatment Alternatives and Options for Patients with Comorbidities, Medically Non-Fit, or Patients or Aged More Than 80 Years

All in all data for very elderly patients, especially those aged 80 years and older are limited. Bellera at al. analysed the specific barriers to include elderly patients with malignant lymphoma (not especially patients with DLBCL) in RCTs and identified restrictive inclusion criteria, poor performance status, impaired liver and kidney function and presence of comorbidities as major reasons [32]. Therefore, data especially for these groups of patients are very limited. In addition to data from RCTs, data from cohort trials in phase II trials have to be included in the recommendations for treatment decision, as they better reflect the typical elderly patients seen in clinics or hospitals.

There is no generally agreed definition, which patient is suitable for a classical R-CHOP regimen. Age is one factor associated with increased toxicity. With the increase in age, treatment related toxicity and mortality increases. Predictors of toxicity are analysed by Ziepert et al. [33]. They separately analysed data for patients aged up to 60 years and above 60 years. Low body weight, female gender, poor PS, high LDH, and initial cytopenia where associated with increased hematological toxicity. According to the results of the RICOVER-60 trial, treatment related death rate was 4 % was patients aged 60–65 years, 6.4 % for those aged 66–70 years, 7.0 % for those aged 70–75 years, and 20.1 % for those aged 76–80 years.

A physicians’ judgement, that the patient is not suitable for a standard R-CHOP regimen can be based on different criteria. Tucci et al. identified, that a geriatric assessment is better to identify patients as fit for treatment than physicians´ judgement [22].

Main strategies followed in the over 80 year old patients and in those unfit for standard R-CHOP treatment are to reduce toxicity of R-CHOP by dose reduction or to use other less toxic drugs.

A variety of studies mainly in the last decade of the last century compared different regimens to CHOP, to find a less toxic protocol. One of the most extensively studies substance, was Mitoxantrone as substitute for Doxorubicin, resulting in CNOP instead of CHOP regimen. In a meta-analysis comparing results of 9 studies, CHOP remained the superior regime regarding efficacy and CNOP was not less toxic. The studies were not restricted to elderly patients, but included a considerable number of older adults [34]. As Rituximab is a very active and less toxic agent, trials using R-Non-CHOP regimens are analysed and reported in Table 11.8.

Table 11.8

Phase II trials of R-Non-CHOP regimen in 1st line treatment

1st author and year | Treatment | N = /Age group/median | % of patients ECOG-PS ≥2 | % of patients aged 80+ | Primary endpoint results | Reasons against CHOP | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Visani et al. (2008) [35] [35] | R-COMP-21 | 20/61–82/73 | 45 | n.r. | CR 63 %, | Frailty | Frail patients |

Corazzelli et al. (2011) BJH [36]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|