CASE HISTORY 2

Senita is a 34-year-old Asian mother of two who attended the antenatal diabetic obstetric clinic following the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) at 17 weeks. Senita had an oral glucose tolerance test at 16 weeks of gestation as she had had GDM in her previous two pre gnancies, both diagnosed at 28 weeks and managed with diet alone. Senita’ s body mass index (BMI) was 31kg/m2 at her 12-week booking visit and when reviewed at 17 weeks, she had already gained 6 kg from her prepregnancy weight. Lifestyle assessment revealed she took no regular exercise and her diet was predominately vegetarian, high in saturated fat and refined carbohydrates.

- What are the basic physiologic energy needs in pregnancy?

- What is the weight gain in normal pregnancy and in pregnancy in women with diabetes?

- What advice should be given regarding diet in normal pregnancy and pregnancy in women with diabetes?

- What advice should be given regarding exercise in normal pregnancy and pregnancy in women with diabetes?

- What advice should be given after pregnancy?

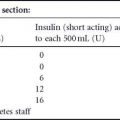

Table 13.1 Components of maternal weight gain in a term pregnancy.1

BACKGROUND

Pregnancy is associated with physiologic changes that optimize the transfer of maternal nutrients to the fetus. Maternal and fetal adaptation occurs throughout pregnancy to ensure the energy requirements of the fetoplacental unit and subsequent lactation are met from a combination of maternal energy intake, maternal adipose stores, and energy conservation through decreased physical activity.

The average total weight gain in pregnancy for a fit non-obese woman is between 10 and 12.5kg.1 This extra weight relates to the feto-placental unit and the increase in maternal tissues (Table 13.1).

Weight gain accelerates in pregnancy with 25% in the first 20 weeks, 25% between 20 and 30 weeks of gestation, and the remaining 50% in the last 10 weeks of pregnancy.

CHANGES IN GLUCOSE METABOLISM RELEVANT TO DIET AND EXERCISE

Normal pregnancy

Glucose is the major fetal fuel substrate and maternal metabolic changes occur throughout pregnancy to optimize its uninterrupted supply to the fetus. Maternal postprandial glucose concentrations rise to facilitate materno-fetal transfer after meals. Paradoxically, in normal pregnancy fasting glucose concentrations decrease at about 10 weeks and remain at this level until birth. A rise in hepatic glucose output, however, ensures a continual glucose supply between meals.

Placental hormones promote maternal insulin resistance and maternal lipolysis; the latter further increases insulin resistance. This rise in maternal insulin resistance effectively diverts glucose away from maternal insulin-sensitive tissues to the fetus. As a consequence, maternal energy requirement becomes increasingly reliant on fat metabolism as the pregnancy progresses (see chapter 2 for more detail).

Pregnancy with diabetes

The pregnancy-related rise in maternal insulin resistance also occurs in women with diabetes. For women with Type 1 diabetes this is apparent by their two-to three-fold increase in insulin requirements by late pregnancy. For women with Type 2 diabetes, who can be managed with diet and oral agents alone prior to pregnancy, the further increase in insulin resistance that occurs inevitably necessitates the need for insulin therapy, with many women requiring a disproportionate increase in insulin demand and high doses of insulin by the third trimester. Similarly, many women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) who start their pregnancy with normal glucose tolerance but with increasing insulin resistance, require therapy (either with oral hypoglycemic drugs or insulin) by the third trimester to maintain adequate glycemic control.2

IS THERE A HEALTHY WEIGHT GAIN FOR PREGNANCY?

Normal pregnancy

There is no international consensus on what is the ideal weight gain for pregnancy. Current guidelines are out-dated as they are based on antenatal populations that were less obese than today’ s and at a time when there was greater concern for preventing low birthweight infants.3 Despite this, there is general agreement that pregnancy weight gain should reflect prepregnancy BMI. For normal weight women, a 10 – 12.5-kg pregnancy weight gain is considered optimal as it is associated with fewer pregnancy-related complications. By contrast, for under-weight women (BMI < 19.8kg/m2), a pregnancy weight gain of 12.5 – 18kg is recommended.

The risk of hypertension, GDM, infections, and need for cesarean birth all increase when weight gain exceeds 10 – 12.5 kg, especially when women start their pregnancies overweight or obese. For obese (>30 kg/m2) and morbidly obese (>40kg/m2) women, little or no weight gain during pregnancy reduces the risk of large for gestational age (LGA) infants and cesarean births, while only minimally increasing the risk of small for gestational age (SGA) infants.4,5 Normal and underweight women who gain less than 7 – 10 kg are at increased risk of giving birth to an SGA infant.

To date no national obstetric body has been prepared to endorse no weight gain. This is despite the data for obese or morbidly obese pregnant women (BMI > 35kg/m2) that the benefits gained in reducing the risk of GDM, hypertension, and an operative birth are likely to out-weigh any adverse risks. Many clinicians currently recommend that pregnancy should be weight neutral for obese women, with no excess weight remaining after the birth. However, there remains a concern about the negative relationship in women who have diabetes between maternal ketonemia and intellectual and motor performance of their children aged 2 – 5 years.6

Pregnancy with diabetes

The pregnancy weight gain targets for women with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, and GDM should be the same as for woman without diabetes. However, this may be difficult to achieve for women on insulin due to their greater dependency on frequent snacks to avoid hypoglycemia. Dietary advice around appropriate food choices taken as snacks and for the management of hypoglycemia is required to prevent unnecessary weight gain as insulin management is intensified. Approximately 20 g of oral carbohydrate is required to manage a typical hypoglycemic episode; suitable food choices for the immediate management for hypoglycemia are listed in Table 13.2.

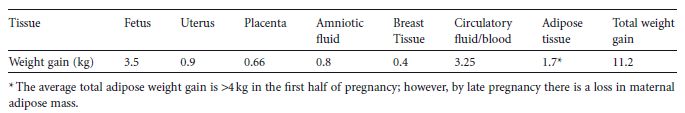

Table 13.2 Immediate management for hypoglycemia.

| Food | Calories 80 | Carbohydrate (g) |

| 4 Jelly babies (Trebor, Nestle) | 80 | 19 |

| 5 Liquorice allsorts (Bassett& Co Ltd, Beacon) | 107 | 23 |

| 6 Wine gums (Bassett & Co Ltd, Maynards) | 126 | 28 |

| 7 Dextrosol tablet | 94 | 23 |

| 100 ml Lucozade Energy | 73 | 26 |

| 250 ml Ribena Original (prediluted) | 128 | 30 |

| ½330-ml can of Fanta Orange | 48 | 16 |

Minimizing unnecessary weight gain in obese women with Type 2 diabetes or GDM can improve maternal glycemic control and improve pregnancy outcomes. Current UK guidelines recommend women with a prepregnancy BMI of greater than 27 kg/m2 to restrict their calorie intake to around 25 kcal/kg/day in the second trimester.7 In comparison, the US Institute of Medicine guidelines (not specific to diabetes) recommend that women with a prepregnancy BMI of 26 – 29 kg/m2 gain a total weight of 7 – 11.5 kg during pregnancy.3 They further recommend a target weight gain of less than 6 kg for women with a pregnancy BMI > 29kg/m2. However, they have subsequently reviewed these guidelines and concluded there is a need for further research, particularly in view of the rising trends in obesity.8

For women with GDM, the introduction of metformin rather than insulin for glycemic management if dietary measures fail could potentially help to limit weight gain, due to less defensive snacking as there is a reduced risk of hypoglycemia associated with metformin compared to insulin. However, there are still concerns around the introduction of metformin in the first trimester as it does cross the placenta and could theoretically be teratogenetic in humans.

FACTORS THAT LIMIT MATERNAL EXERCISE

Normal pregnancy

Sensible moderate exercise is to be encouraged in pregnancy; contact sports, high impact sports, and sport undertaken alone or in remote places, together with those commonly referred to as “extreme sports”, are not recommended. Scuba diving should be avoided throughout pregnancy as the fetus is not protected from problems arising from decompression; both the risks of malformation and gas embolism have been associated with decompression disease.

Exercising in the supine position in late pregnancy can potentially cause aorto-caval compression and should be avoided. It is important to ensure adequate hydration during exercise, especially in hot weather.

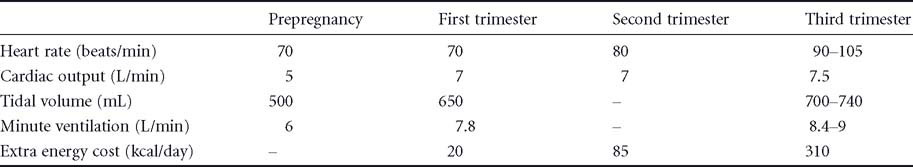

In fit and active women, a number of cardiovascular and respiratory changes occur as pregnancy progresses that directly affect and limit exercise tolerance (Table 13.3).As pregnancy advances there are also physical limitations due to the increasing size of the gravid uterus. Exercise tolerance is further compromised by the third trimester as the uterus splints the diaphragm (Table 13.3).

Table 13.3 Cardiovascular and respiratory changes in normal pregnancy.9–11

Normal physiologic changes by late gestation result in a sensation of breathlessness and respiratory discomfort that may limit exercise. A combination of the increased resting and effort minute ventilation and tachycardia can be associated with a perception of anxiety and apprehension that by late pregnancy can limit exercise tolerance.12

With increasing gestation, joint laxity, pubic symphysis dysfunction, and backache can also limit a woman’s ability to exercise. These muscular skeletal problems become more problematic with increasing parity and obesity.

Pregnancy with diabetes

All women with diabetes experience cardiovascular and muscular skeletal changes in pregnancy similar to those of women without diabetes. The problems encountered with exercise, however, are different for women with Type 1 diabetes than for women with Type 2 diabetes or GDM, and therefore need to be considered separately.

Exercise creates challenges throughout pregnancy for women with Type 1 diabetes, the most common and potentially most serious being hypoglycemia. The risk for exercise-induced hypoglycemia is increased in pregnancy due to decreased hypoglycemic awareness and the attenuated adrenergic response to a fall in blood glucose. Quite modest exercise, such as encountered traveling to work, doing the housework, and shopping, needs to be proactively and individually factored into daily insulin and dietary management. More strenuous exercise, such as aerobics, swimming, and jogging, that may outside pregnancy be well tolerated, will require ongoing individual review and assessment throughout pregnancy, and may need to be curtailed altogether if hypoglycemia persists.

Many women with Type 2 diabetes and GDM enter pregnancy with poor exercise tolerance, having done little or no regular exercise beforehand. Limitations in increasing physical activity in overweight gravid women with Type 2 diabetes and GDM include their increased risk for muscular skeletal problems and other comorbidities.

For all women with Type 2 diabetes or GDM, any increase in exercise, especially postprandial, is potentially beneficial to the pregnancy as it helps to limit postprandial hyperglycemia, weight gain, and insulin requirements. A physical activity program combined with dietary modification and intensive glycemic management has been shown to reduce perinatal complications in women with GDM.13 Exercise programs based on 20 minutes of arm movements three times a week and/or weekly resistance exercises three times a week have been found to lower fasting blood glucose,1-hour postprandial blood glucose, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in women with GDM, as well as reducing the need for insulin when compared with diet alone.14,15 Exercise does,however,need to be sustained throughout pregnancy.16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree