CHAPTER 8 Diet and Disease

At the end of this chapter you should be able to

• describe the prevalence of important chronic diseases in different parts of the world and be aware of the changing mortality rates in different countries

• use appropriate terminology to define and describe the disease or condition

• describe the process of development of the disease or condition

• describe the risk factors for the diseases and their nutritional and other determinants

• discuss the short- and long-term risks

8.2 CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases account for a significant proportion of total morbidity and mortality in adults throughout the world. An understanding of the following terms should be useful in interpreting the literature.

Prevalence of cardiovascular disease

Box 8.1 shows accepted risk factors for CHD. These include non-modifiable factors such as age or gender, and lifestyle factors including smoking, physical activity and diet, or their biomarkers. Risk factors for CHD have principally been identified in prospective cohort studies. Many of these modifiable factors are associated with a graded increase in risk and in the case of cholesterol and blood pressure there is convincing evidence from randomized controlled intervention trials that lowering the risk factor reduces risk.

Epidemiological and experimental evidence linking diet with cardiovascular disease

The link with saturated and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids

The Seven Countries Study of Ancel & Keys and co-workers was absolutely central to our early understanding of a link between dietary intake and CHD risk. This study examined the associations between dietary intakes and 10-year CHD mortality rates of 16 population groups in seven countries. A strong correlation was noted between CHD and the percentage of energy derived from saturated fat and weaker inverse associations were found between CHD and percentages of energy derived from monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat. Saturated fat was believed to increase coronary heart disease risk because of its ability to elevate blood cholesterol levels, and polyunsaturated fat (chiefly n-6 fatty acids) provided its modest protective effect via cholesterol-lowering. These observations led to many more studies and it is now clear that dietary saturated and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids act predominantly through effects on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, for which total cholesterol is a surrogate measure. In fact the effect of altering dietary cholesterol on LDL is much smaller than the effects of altering the intakes of various fatty acids. Experimental studies have shown large inter-individual variation in the lipoprotein responses to altering lipid intakes. It is thought that this can be explained by polymorphisms in key genes, but what these gene polymorphisms are is not yet clear. Saturated fatty acids can also increase CHD risk through mechanisms other than effects on lipoproteins, including a lowering of insulin sensitivity and an increase in platelet aggregation.

Nutritional and dietary determinants of cardiovascular risk

Understanding the relationships between diet and cardiovascular disease risk depends upon reliable methods for estimating dietary intake as well as accurate incidence or mortality statistics. Early studies used national food consumption data, the food balance sheets of the Food and Agriculture Organization, or household food surveys. Positive associations with saturated fat, sucrose, animal protein and coffee, and negative correlations with flour (and other complex carbohydrates) and vegetables are some of the associations described. However, these early studies were important principally as hypothesis-generating and could not prove cause and effect.

B vitamins

Folate and vitamins B2, B6 and B12 may help to protect against cardiovascular disease through effects on the metabolism of the amino acid homocysteine. Many (mainly case-control) studies have shown that an elevated plasma homocysteine concentration is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Diets rich in folate tend to be associated with low plasma homocysteine, and supplements of folic acid, or vitamins B2, B6 or B12 all have homocysteine-lowering potential. However, there is little convincing evidence that lowering plasma homocysteine reduces risk of cardiovascular disease.

Cardioprotective dietary patterns

A number of dietary patterns across the globe have been shown to be protective against CHD (Box 8.2). These include the Mediterranean diet, which traditionally has high intakes of fruit and vegetables and unsaturated vegetable oils; and certain traditional Asian diets. Unfortunately, health benefits associated with such traditional diets are being lost with the transition to more contemporary lifestyles.

Box 8.2 Attributes of cardioprotective diets

• Low intakes of saturated fatty acids

• High intake of raw or appropriately prepared fruit and vegetables

• Lightly processed cereal foods and wholegrains are preferred

• Fat intakes are derived predominantly from unmodified vegetable oils*

• Fish, nuts, seeds and vegetable protein sources are important dietary components

• Meat, when consumed, is lean and eaten in small quantities

Clinical trials of dietary modification

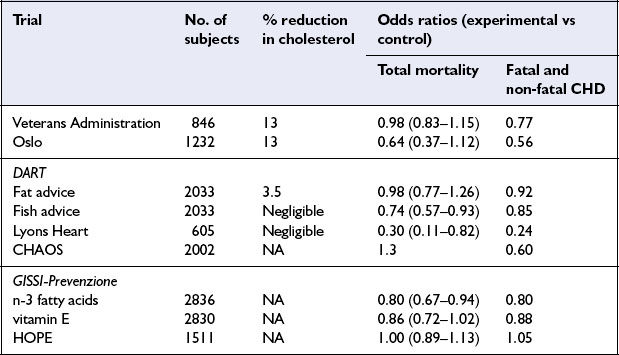

While prospective epidemiological studies provide strong evidence of risk or protection associated with individual nutrients or foods, proof of causality and the ultimate level of evidence for dietary recommendations requires randomized controlled trials. The early trials all focused on lowering cholesterol levels, usually by increasing the dietary polyunsaturated:saturated (P:S) ratio. More recent trials have involved multifactorial interventions, including dietary change intended to improve all nutrition-related risk indicators as well as attempts to modify risk factors which are not diet-related, such as cigarette smoking. Dietary intervention trials have been undertaken in people with and without evidence of CHD at the time the study was started – called secondary and primary prevention trials respectively. This section describes briefly a few landmark trials (Table 8.1) and presents an overview of the important investigations of this kind.

The Lyons Heart Study was a secondary prevention trial among men with ischaemic heart disease. Patients either received conventional dietary advice or advice to follow a traditional Mediterranean diet which included more bread, legumes, vegetables and fruit and less meat and dairy products. This diet was lower in saturated fat and richer in n-3 fatty acids than the control diet. The group consuming the Mediterranean diet experienced a reduction in cardiovascular events as well as total mortality.

Conclusions

Cholesterol lowering by dietary means reduces coronary events in the context of both primary and secondary prevention. An increase in polyunsaturated fatty acids, a reduction in saturated fatty acids, and an increase in non-starch polysaccharide (dietary fibre) and starch, may all help to reduce cardiovascular risk. Monounsaturated fatty acids have a neutral effect. Antioxidant nutrient supplementation is less likely to be effective.

• The nature of dietary fat is an important determinant of CHD in populations

• Saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids increase CHD risk; n-6 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are protective

• Antioxidant nutrients, flavonoids, folate and other B vitamins, non-starch polysaccharides, whole grain cereals, nuts, soy protein and alcohol may protect against CHD

• Randomized controlled clinical trials demonstrate the potential for dietary change to reduce CHD rates

8.3 DIABETES

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder of multiple aetiology characterized by chronic hyperglycaemia associated with impaired carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism. These abnormalities are the consequence of either inadequate insulin secretion or impaired insulin action, or both. A diagnosis of diabetes mellitus is made on the basis of elevated plasma glucose concentration, either in a fasted or non-fasted blood sample or following a glucose load. The three most common forms are type 1, type 2 and gestational diabetes, which is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy. Type 2 diabetes is often associated with other metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk factors, collectively referred to as the metabolic syndrome (see section 8.5).

Aetiology and pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

Type 1 diabetes is considered to be an autoimmune disease characterized by a cell-mediated autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β-cells that results in a partial or total inability to secrete insulin, and life-long need for insulin administration. Genetic factors make an important contribution to this condition but do not fully explain its aetiology. Environmental factors could contribute to the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes mellitus through a direct toxic effect on the β-cells, triggering an autoimmune reaction against the β-cells, or damaging β-cells so as to increase their susceptibility to autoimmune destruction. Environmental factors include drugs or chemicals, viruses and dietary factors. There is, for example, evidence for a close relationship between cow’s milk consumption and incidence of type 1 diabetes in childhood.

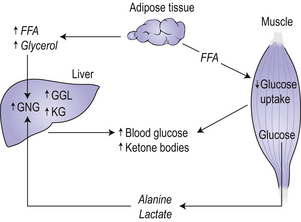

Type 1 diabetes develops over many years, and can be considered as a multistage process starting with a genetic susceptibility, requiring a triggering event, progressing to active autoimmunity, gradual loss of glucose-induced insulin secretion and finally to overt diabetes. In metabolic terms, a failure to secrete insulin leads to hyperglycaemia because of increased glucose production by the liver and reduced glucose utilization by peripheral tissue (Fig 8.1). The liver increases the rate of gluconeogenesis from extrahepatic fuels including alanine, lactate and glycerol. Glucose utilization decreases as a result of the failure of insulin to adequately facilitate glucose entry into cells, resulting in an increased availability of free fatty acids. An increased rate of fatty acid oxidation leads to an increase in the production of ketone bodies by the liver. Ketone bodies are an important fuel for the brain in times of reduced glucose availability. All these metabolic abnormalities account for the classic symptoms and signs of the disease, such as glycosuria, polyuria, polydipsia (thirst), and weight loss.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Type 2 diabetes mellitus accounts for the great majority of all cases of diabetes. Type 2 diabetes, until recently referred to as non-insulin-dependent diabetes, is characterized by disorders of insulin action and secretion. These individuals may not require insulin treatment. Most of these patients are obese or have increased body fat predominantly in the abdominal region. The incidence and prevalence is increasing in the adult population but reports also indicate an emerging problem among children and adolescents.

Vascular complications

Microvasculature

Patients with diabetes can develop a number of complications, including those of the vasculature. Retinopathy can result from abnormalities in the microvasculature, is a feature of longstanding type 1 diabetes and can occur in type 2 diabetes. In some patients this leads to blindness. Nephropathy (damage to the kidney) occurs in about one-quarter of patients with type 1 diabetes, but is much rarer in type 2 diabetes.

Management of diabetes mellitus

Diet

Dietary intervention can also be effective in preventing the onset of type 2 diabetes in high risk individuals. Intervention trials have shown that weight loss achieved in high risk individuals consuming diets with reduced saturated fat and increased dietary fibre, in conjunction with increased physical activity, can reduce risk of type 2 diabetes.

Hypoglycaemic oral agents and insulin therapy

Patients with type 2 diabetes who do not respond adequately to a diet and exercise regimen will be given oral hypoglycaemic medication. Metformin induces weight loss and contributes to the normalization of blood glucose and for these reasons is considered the first choice drug in the treatment of overweight diabetic patients. Sulphonylureas are generally employed for normal weight patients. If adequate glucose control is not achieved with the use of either or both of these drugs or other drugs in current use, insulin therapy can be included in the treatment.

• Diabetes mellitus is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Its prevalence is increasing globally, both in adults and children, due to increased prevalence of obesity and low levels of physical exercise

• Type 1 diabetes is characterized by impaired insulin secretion and requires insulin therapy to prevent ketoacidosis and death

• Type 2 diabetes is frequently associated with obesity and is caused by a defect in β-cell function and insulin resistance

• Lifestyle modification including dietary change and increased physical activity can improve prognosis

8.4 CANCERS

Distribution of cancers throughout the world

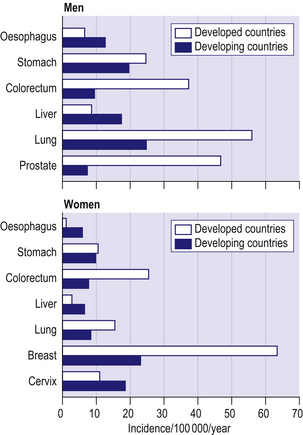

Figure 8.2 shows age-standardized incidence rates for the common cancers in developed and developing countries. Lung cancer is the commonest cancer in men in both developed and developing countries. Cancers of the prostate and colorectum are the next most common in developed countries whilst in developing countries cancers of the stomach and liver are the most common after lung cancer. Breast cancer is by far the most common cancer among women in both developed and developing countries. Cancers of the colorectum and lung are the next most important in developed countries, whilst in developing countries cancer of the cervix has a similar incidence to breast cancer.

Cancer rates in the UK

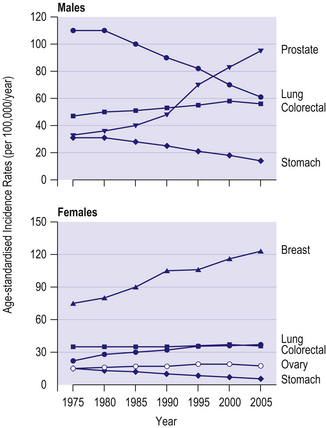

The four commonest cancers in the UK are cancers of the lung, breast, colorectum and prostate – together these account for over half of all new cancer cases. In men, lung cancer rates have shown a steady fall since the 1970s due to reductions in cigarette smoking (Fig 8.3). In contrast, prostate cancer rates have increased markedly over the last 40 years, due partly to increased and earlier detection. In women, breast cancer incidence rates have increased over the last 40 years, with a steep increase around 1990 largely due to increased and earlier detection. Lung cancer rates have increased substantially in women due to increases in cigarette smoking.

Pathophysiology of cancer

Most cancers develop from a single cell that grows and divides more than it should, resulting in the formation of a tumour or cancer. Cancers growing in most tissues take the form of a lump that grows, invades local non-cancerous tissues, and may spread to other parts of the body through the bloodstream. Cancers arising in the cells of the blood, such as leukaemia, do not form a lump because the cells are floating freely throughout the bloodstream. Most deaths due to cancer are caused by the spread of the cancer from its site of origin into adjacent areas and to other parts of the body. The transfer of the cancer from one site to another site not directly connected with it is called metastasis.

Inherited genetic factors in carcinogenesis

For the common types of cancer, current estimates are that inherited genetic factors contribute no more than 5% to the cases of cancer arising in a population. Inherited genetic factors (as opposed to mutations in genes that can occur during a person’s lifetime) can be considered in two classes: high risk mutations and low risk genetic polymorphisms.

Low risk polymorphisms: Mutations that occur with a frequency of more than 1% in a population are termed polymorphisms and they typically confer only a small increase in risk for cancer and do not cause clusters of cancers in families. There is currently great interest in the impact that gene polymorphisms can have on the cancer burden of a population, and the interaction of diet with gene polymorphisms is an area of active current research (see chapter 11).

Non-dietary causes of cancer

The proportions of cancer due to avoidable causes have been estimated by Doll & Peto and are shown in Table 8.2. These estimates apply to Western countries such as the USA or the UK; in developing countries the proportion of cancer due to infective factors would be higher. Worldwide, the most important preventable cause of cancer is tobacco, which causes cancers of the mouth, pharynx, oesophagus, larynx, lung, pancreas, kidney (pelvis) and bladder. Infectious agents are responsible for about 9% of cancers worldwide, with the proportion being higher in developing countries. For example, hepatitis B and C viruses cause liver cancer, human papillomavirus causes cervical cancer and the trematode worm, Schistosoma haematobium, is a major cause of bladder cancer in Egypt and Tanzania. Hormonal and reproductive factors are important determinants of cancers of the breast, ovary and endometrium and childbirth reduces the risk for all three. Ionizing radiation makes a modest contribution to cancer causation; in the UK, for example, approximately 5% of lung cancers are due to naturally occurring radon gas inside buildings. Finally, a small proportion of cancers is caused by factors such as ultraviolet light, medical drugs, occupational exposures and pollution.

Table 8.2 Proportions of cancer deaths attributable to different lifestyle and environmental and behavioural factors in countries such as the United Kingdom

| Factor | Best estimate of proportion (%) |

|---|---|

| Tobacco | 30 |

| Diet | 25 |

| Hormonal factors | 15 |

| Alcohol | 6 |

| Infections | 5 |

| Ionizing radiation | 5 |

| Occupation | 2 |

| Pollutants | 2 |

| Ultraviolet light | 1 |

| Medical drugs | <1 |

Adapted from Doll & Peto 2003

Diet and cancer

For all the common cancers, rates vary widely between populations in different parts of the world and when people migrate from one country to another they typically adopt the cancer rates of their new host country, indicating the importance of environment in determining cancer risk. Comparisons of dietary patterns and cancer rates in different countries have generated useful hypotheses linking diet with cancer risk. For example, this type of study led to the hypothesis that high intakes of meat may increase the risk for colorectal cancer, and that high intakes of fat may increase the risk for breast cancer. Hypotheses generated by these sorts of studies can be tested in case control and prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials (refer to chapter 12 for an explanation of study design).