Premalignant lesions

Conditions which may be associated with invasive carcinoma

Clinical

Erythroplasia of Queyrat

Lichen sclerosus

Bowen’s disease

Penile cutaneous horn

Bowenoid papulosis

Cutaneous

Verrucous hyperplasia

Histopathological

Undifferentiated PeIN

Differentiated PeIN

Aetiology of Premalignant Lesions

There are a number of well-known risk factors for the development of penile cancer and premalignant lesions. These include infection with human papillomaviruses (HPV), lichen sclerosus (LS), the uncircumcised state, phimosis, chronic inflammation, immunosuppression and smoking. Apart from HPV and LS, which have been investigated specifically for their role in premalignancy, most factors have only been investigated for their association with invasive malignancy.

Immunosuppression, particularly in the HIV and AIDS population, increases the relative risk of penile cancer (RR, 3.9; 95 % CI, 2.1–6.5), as well as leading to a younger age at presentation [1].

Cigarette smoking has been associated with a four- to fivefold risk of developing invasive penile cancer. This association was found to be dose dependent and independent of coexisting phimosis [2].

The role of circumcision in penile cancer prevention is controversial. A systematic review of male circumcision and penile cancer found a strong protective effect of childhood/adolescent circumcision on invasive penile cancer (odds ratio 0.33) [3]. Four studies in the same systematic review found a strong association between the presence of phimosis and invasive cancer (OR 4.9–37.2). The theory for the relationship between the uncircumcised state and the presence of phimosis with penile cancer is that of chronic inflammation caused by poor hygiene. There is no evidence for a carcinogenic role of smegma [4]; however, it is likely to contribute to chronic inflammation. There is also evidence that circumcision reduces the incidence of HPV and HIV infection, themselves risk factors for penile cancer.

HPV is the most studied risk factor for penile cancer with HPV DNA detected in up to 50 % of tumours, and the most important risk factor for HPV infection is increasing number of sexual partners. Sixty percent are HPV subtype 16 and 13 % subtype 18 [5]. HPV infection is therefore further divided into ‘high-risk’ subtypes 16 and 18 and the less common ‘low-risk’ subtypes including 6 and 11. The clinically defined lesions associated with HPV will be discussed in subsequent sections.

Dermatoses such as lichen sclerosus and penile cutaneous horn have an association with penile cancer. Other texts refer to these lesions as premalignant [6]. This is a contentious issue as the lesions in themselves are benign. We subsequently refer to these as lesions associated with in situ disease and invasive SCC.

Histopathological Terminology

A number of terms have been used in the histopathological classification of premalignant penile lesions. These include penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN), squamous carcinoma in situ (CIS), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL). In some systems, PeIN was originally graded from I to III (low to high grade).

More recently Velazquez et al. [7] have proposed a simplified system encompassing all these terms and dividing the changes into undifferentiated or differentiated PeIN and have done away with the terms low grade and high grade and with subtyping of PeIN into grades I–III.

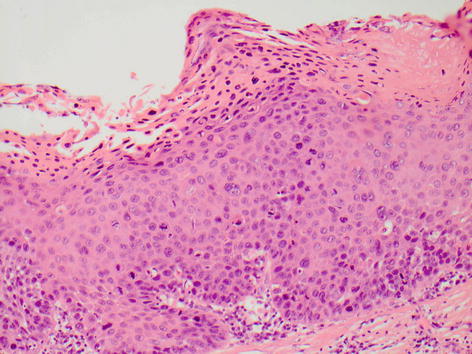

Undifferentiated PeIN encompasses squamous carcinoma in situ, severe epithelial dysplasia and the clinically defined mucosal erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen’s disease of the penile skin. Undifferentiated PeIN is subdivided into basaloid and/or warty subtypes and is frequently associated with HPV 16. Histologically this lesion shows full thickness cytological atypia with lack of differentiation and abnormal mitotic activity (see Fig. 7.1). Undifferentiated PeIN is associated with warty and basaloid invasive carcinomas [8] but may also be seen with usual type squamous carcinoma. Bowenoid papulosis shows the features of warty undifferentiated PeIN and can only be defined clinically.

Fig. 7.1

Undifferentiated PeIN

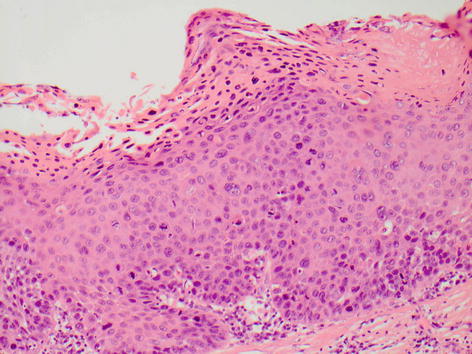

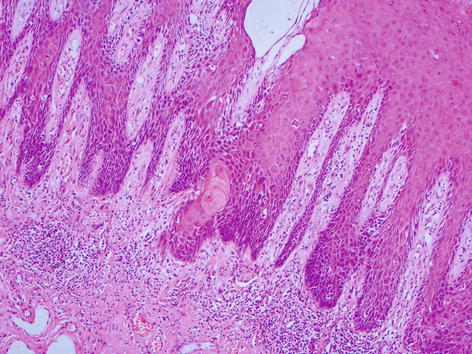

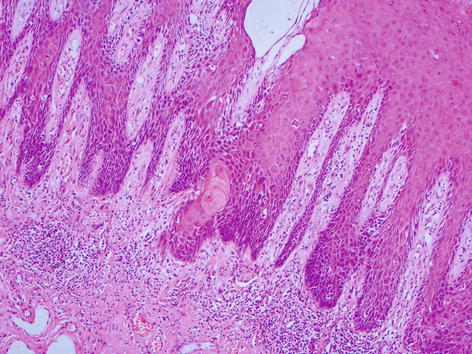

Differentiated PeIN has only been described and defined more recently. Histologically the atypical squamous cells are confined to the lower layers of the penile squamous epithelium and are usually associated with architectural atypia, elongated rete ridges and aberrant intraepithelial keratinisation (see Fig. 7.2). It is often associated with verrucous hyperplasia and lichen sclerosus. It is not associated with high-risk HPV subtypes.

Fig. 7.2

Differentiated PeIN

Clinically Defined Premalignant Lesions

Erythroplasia of Queyrat (EQ) (Fig. 7.3)

Fig. 7.3

Erythroplasia of Queyrat

Erythroplasia of the glans penis was first described by Queyrat in 1911. EQ affects the mucosal surfaces of the penis (glans, inner prepuce or distal urethra) and has a number of clinical presentations. Lesions can vary from patchy erythema to diffuse shiny erythema with or without erosions. EQ can also present as well-demarcated velvety plaques, which can coalesce to form a large contiguous plaque. They are often painless but can be extremely painful with the presence of erosions. Transformation into invasive carcinoma has been reported in up to 33 % of cases [9]. Histopathologically these lesions show undifferentiated PeIN.

Bowen’s Disease (BD) (Fig. 7.4)

Fig. 7.4

Bowen’s disease

Bowen’s disease is histologically indistinguishable from erythroplasia of Queyrat; however, it involves non-mucosal skin rather than penile mucosa. It usually presents as a single well-defined plaque of scaly erythema. The appearances can vary with ulcerated, keratotic or elevated flesh-coloured plaques described. Lesions may even become heavily pigmented and resemble melanoma. Malignant transformation has been reported in 5 % of cases [10].

Bowenoid Papulosis (BP) (Fig. 7.5)

Bowenoid papulosis occurs mainly in sexually active young men and is strongly associated with HPV subtype 16. It is characterised by pink, velvety papules. The papules are often multiple and can coalesce into plaques. Lesions tend to occur on the penile shaft or mons pubis where they often appear more pigmented. They are less frequently found on the glans or inner prepuce. Lesions can be pruritic but are often asymptomatic. Histologically the lesions show undifferentiated PeIN with warty features. However, it tends to run a more benign course with malignant transformation seen in less than 1 % of cases [11].

Giant Condyloma Accuminatum (Buschke-Lowenstein Tumour) (Fig. 7.6)

Fig. 7.6

Giant condyloma accuminatum

Giant condyloma accuminatum (GCA) was first described by Buschke and Lowenstein in 1925. This large, exophytic, cauliflower-like growth results from a confluence of condyloma acuminata, smaller warty growths that can affect any part of the anogenital region. On the penis these lesions tend to be found in the coronal sulcus and frenulum. They have a strong association with HPV 6 and 11. Although GCA was thought originally to be benign, the lesion is now thought to be a type of warty carcinoma, and careful examination of these lesions often shows invasion [12]. Older literature refers to GCA interchangeably as verrucous carcinoma. It is now widely accepted that GCA and verrucous carcinoma are two distinct pathologies due to the well-documented role of HPV in the pathogenesis of GCA, which is not commonly seen with verrucous carcinoma.

Verrucous Hyperplasia (Fig. 7.7)

Fig. 7.7

Verrucous hyperplasia

Verrucous hyperplasia appears as thickened pale areas of mucosa without nodularity. Histologically there is epithelial hyperplasia with elongation of broad rete ridges without cytological atypia. It is thought to be a premalignant lesion leading to verrucous carcinoma and should be excised with a narrow margin [13].

Lesions Associated with In Situ Disease and Invasive SCC

Lichen Sclerosus (Fig. 7.8)

Fig. 7.8

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition of unknown aetiology. Lesions appear as white plaques on the prepuce and glans. The resulting sclerosis can cause phimosis, adherence of the prepuce to the glans, meatal stenosis and urethral strictures.

A number of studies have shown a strong association between LS and penile cancer. Several studies comment on the presence of synchronous penile cancer in LS specimens. Barbagli et al. reviewed the histology of 130 patients with male genital lichen sclerosis and reported the finding of malignant or premalignant lesions in 11 (8.4 %) of the specimens [14]. Nasca et al. reviewed the histology of 86 patients over a 10-year period, finding malignant or premalignant lesions in 5 (5.8 %) of the samples [15]. In the largest series to date, Depasquale et al. identified 12 patients with squamous cell carcinoma from 522 patients (2.3 %) treated for LS over a 14-year period [16]. Seven of these patients had been previously circumcised for LS and later developed SCC, and five had LS in uncircumcised penises. There was no reference to the inclusion of premalignant lesions in this study, which may account for the rates being lower than those reported in other series. In another smaller series, Campus et al. identified SCC in 2 of 54 patients treated for LS (3.7 %) [17].

There are also a number of studies that report the synchronous finding of LS in the histology of excised malignant and premalignant penile lesions. Velazquez and Cubilla identified synchronous LS in 68 of 207 penile SCC specimens (32.8 %) [18]. Pietrzak et al. identified synchronous LS in 44 of 105 patients with penile SCC or CIS (28 %) [19]. A recent study by Chaux et al. showed the association of LS with differentiated PeIN in 39 of 77 cases (51 %) [20]. Mannweiler investigated the association of LS with 35 patients with differentiated PeIN or HPV and p16INK4a over-expression negative SCC. 26 (74.3 %) of these patients had synchronous LS [21].

Where patients have undergone circumcision for LS, we would advise that the prepuce is always sent for histological analysis to look for differentiated PeIN. Further follow-up depends on the extent of persistent glanular and/or urethral changes. A relatively normal-appearing glans does not require outpatient follow-up, and the patient can be advised to perform regular self-examination. If the glans is particularly inflamed, a period of topical steroid use and follow-up is advised.

Penile Cutaneous Horn (Fig. 7.9)

Penile cutaneous horn describes a conical, protruding, hyperkeratotic mass usually arising from the glans or coronal sulcus. In most cases, there is a history of chronic inflammation and phimosis. The base of the lesion can show dysplastic changes amounting to differentiated PeIN, and these lesions may also be associated with hyperplastic lichen sclerosus.

Diagnosis

Any suspected premalignant lesion of the penis should be biopsied to confirm the diagnosis and rule out invasive disease or other benign penile dermatosis. This should ideally be a full thickness incision of a representative area of the lesion or an excision biopsy if possible. Excision is relatively straightforward with lesions of the prepuce and shaft skin such as Bowen’s disease or bowenoid papulosis; however, complete excision of a large area of the glans (EQ) may not be possible due to potential disfigurement. We would advise that these lesions have a generous incision biopsy as they have a tendency to be under staged and architectural subtlety may not be appreciated on a smaller punch biopsy or scraping.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree