Fig. 11.1

The peritoneal cancer index uses the distribution of cancer implants throughout the abdomen and pelvis combined with a lesion size of these nodules in order to quantitate the disease upon abdominal exploration

CC is a quantitative prognostic indicator determined once the surgical resection has been completed. A patient receives a CC-0 score when no visible peritoneal carcinomatosis remains after cytoreduction, CC-1 is recorded when tumor nodules persist after cytoreduction but they measure less than 0.25 cm, and CC-2 when remaining tumor measures between 0.25 and 2.5 cm. When tumor nodules are greater than 2.5 cm or there is confluence of unresectable tumor, a CC-3 score is given to the patient. Many prior studies in ovarian cancer have shown that the extent of disease remaining after cytoreduction is directly related to the survival [47–54].

Surgical Techniques Used to Complete Cytoreduction in Selected Patients

The goal of CRS is to reduce the tumor burden within the abdomen and pelvis to its absolute minimal volume. The best result is a patient who is visibly free of disease at the close of the procedure. The surgery combines a series of peritonectomy procedures and visceral resections. The peritonectomy procedures include anterior parietal peritonectomy, stripping of right and left hemidiaphragm, pelvic peritonectomy, and omental bursa peritonectomy. Visceral resections include hysterectomy and oophorectomy, greater and lesser omentectomy, splenectomy, right colectomy, and rectosigmoid colectomy.

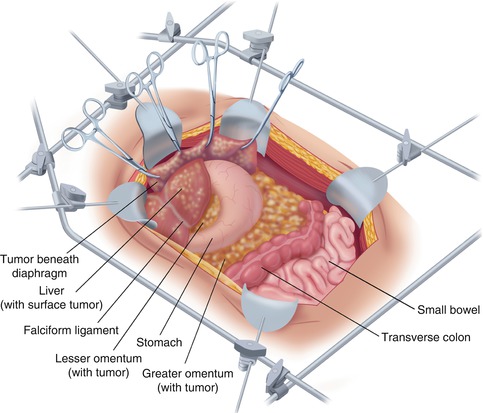

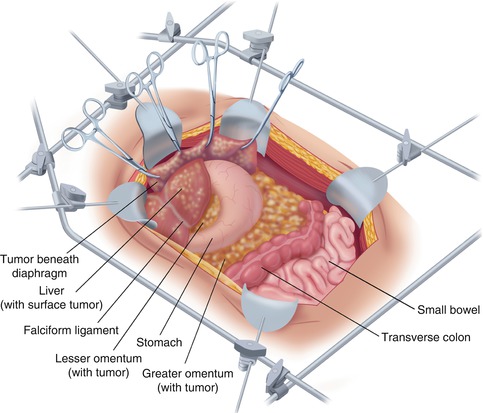

Construction of the Surgical Field to Provide Simultaneous Exposure of the Abdomen and Pelvis

A self-retaining retractor (Thompson Surgical Instruments, Traverse City, Michigan) is positioned so that continuous retraction of all parts of the abdominal incision occurs (Fig. 11.2). The retraction system must be securely anchored to the operating table to provide for continuous unencumbered visualization of a large operative field. An incision starting above the xiphisternal junction and continuing down the pubis through the midline is constructed. An ellipse is created around the umbilicus to allow for the peritoneal plane to be clearly exposed throughout the extent of the abdominal incision. The fascia is divided through the linea alba from the xiphoid bone to the pubic bone. If there has been prior midline abdominal incision, it is widely excised. Routinely, the xiphoid is completely resected at the xiphisternal junction as part of the specimen. With the fascia divided, the parietal peritoneum remains intact.

Fig. 11.2

A fixed retractor is used to provide exposure of the entire abdomen so that peritonectomy procedures on the anterior abdominal wall, beneath the hemidiaphragms, and within the pelvis can proceed in an efficient manner (From Sugarbaker PH. An overview of peritonectomy, visceral resections, and perioperative chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy. In: Sugarbaker PH. (ed.) Cytoreductive Surgery and Perioperative Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Surface Malignancy. Woodbury, CT: Textbook and Video Atlas. Cine-Med Publishing; 2012. pp. 1–30)

Parietal Peritoneal Stripping from the Anterior Abdominal Wall

A single entry into the peritoneal cavity in the middle portion of the incision allows the surgeon to assess the parietal peritoneum and the small bowel surfaces. If cancer nodules are palpated on the parietal peritoneum larger than those covering the small bowel and its mesentery, a decision for a complete dissection is made. Except for the small defect in the peritoneum required for this peritoneal exploration, the remainder of the peritoneum is kept intact to facilitate the peritonectomy.

Stripping the Visceral Peritoneum from the Surface of the Bladder

After dissecting generously the peritoneum on the right and left sides of the bladder, the apex of the bladder (preferably the urachus) is localized and placed on strong traction using a Babcock clamp. The peritoneum with the underlying fatty tissues is stripped away from the muscular surface of the bladder. Broad traction on the entire anterior parietal peritoneal surface and frequent saline irrigation reveals the point for tissue transection that is precisely located between the bladder musculature and its adherent fatty tissue. This dissection is continued inferiorly down to the cervix in the female or to the seminal vesicles in the male.

Parietal Peritoneal Dissection to the Paracolic Sulcus and Beyond

The self-retaining retraction system is steadily advanced more deeply into the abdominal cavity. Firm broad traction on the peritoneum at the point of dissection facilitates accurate dissection. The peritoneum strips readily from the undersurface of the hemidiaphragm. The dissection joins the right and left subphrenic peritonectomy superiorly and the complete pelvic peritonectomy inferiorly. As the dissection proceeds beyond the peritoneum overlying the paracolic sulcus (line of Toldt), the dissection becomes more rapid because of the loose connections of the peritoneum to the underlying fatty tissue at this anatomic site.

When the anterior parietal peritonectomy has been completed, removal of this large peritoneal layer eradicates cancer implants from the posterior aspect of the anterior abdominal wall. Complete exploration of the abdomen and pelvis proceeds.

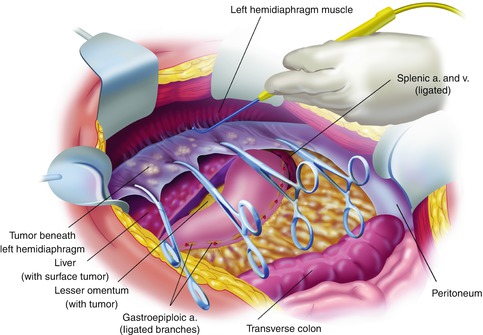

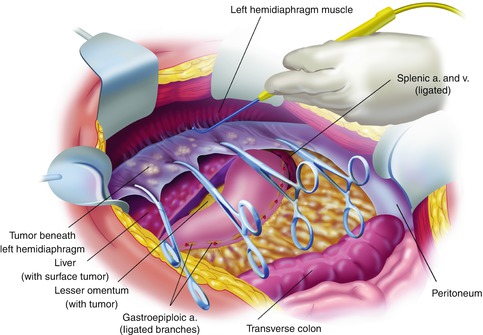

Peritoneal Stripping from Beneath the Left Hemidiaphragm

To begin peritonectomy of the left upper quadrant, the peritoneum is progressively stripped off the posterior rectus sheath (Fig. 11.3). Broad traction must be exerted on the tumor specimen throughout the left upper quadrant. Strong traction combined with ball-tipped electrosurgical dissection allows separation of the peritoneum with tumor from all normal tissue in the left upper quadrant including the diaphragmatic muscle, the left adrenal gland, and the superior aspect of perirenal fat. The splenic flexure of the colon is released from the peritoneum of the left abdominal gutter and moved medially.

Fig. 11.3

Left upper quadrant peritonectomy (From Sugarbaker PH. An overview of peritonectomy, visceral resections, and perioperative chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy. In: Sugarbaker PH. (ed.) Cytoreductive Surgery and Perioperative Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Surface Malignancy. Woodbury, CT: Textbook and Video Atlas. Cine-Med Publishing; 2012. pp. 1–30)

Greater Omentectomy and Splenectomy with Completion of the Left Subphrenic Peritonectomy

To free the mid-abdomen of a large volume of tumor, the greater omentectomy–splenectomy is performed. The greater omentectomy is elevated and then separated from the transverse colon using electrosurgery. The omental tissue on the anterior aspect of the transverse mesocolon is also resected. The gastroepiploic vessels on the greater curvature of the stomach are ligated and divided. Also, the short gastric vessels are transected. This freely exposes the splenic artery and vein at the tail of the pancreas. These vessels are ligated in continuity and proximally suture ligated taking care not to traumatize pancreas parenchyma. This allows the greater curvature of the stomach to be reflected to the right from the pylorus to the gastroesophageal junction.

Peritoneal Stripping from Beneath the Right Hemidiaphragm

Peritoneum is stripped away from the right posterior rectus sheath to begin the peritonectomy in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Strong traction on the specimen is used to elevate the rolled muscular edge of the hemidiaphragm into the operative field. Again, ball-tipped electrosurgery on pure cut is used to dissect at the interface of tumor and normal tissue. Coagulation current is used to divide the blood vessels as they are encountered and before they bleed.

Cholecystectomy, Lesser Omentectomy, and Peritonectomy of the Omental Bursa

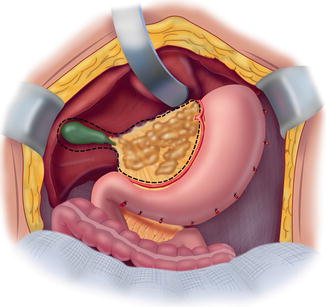

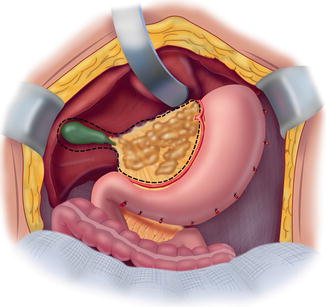

The gallbladder is removed in a routine fashion from its fundus toward the cystic artery and cystic duct (Fig. 11.4). Blunt dissection of the cystic artery and cystic duct away from the common duct and right hepatic artery distinguishes these structures from the surrounding tumor and fatty tissue. These structures are ligated and divided.

Fig. 11.4

Cholecystectomy, lesser omentectomy, and peritonectomy of the omental bursa (From Sugarbaker PH. An overview of peritonectomy, visceral resections, and perioperative chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy. In: Sugarbaker PH. (ed.) Cytoreductive Surgery and Perioperative Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Surface Malignancy. Woodbury, CT: Textbook and Video Atlas. Cine-Med Publishing; 2012. pp. 1–30)

To strip the peritoneum from the anterior aspect of the hepatoduodenal ligament, its peritoneal reflection to the liver surface is divided. Special care is taken not to injure the left hepatic artery, which is usually the most superficial of the portal structures. The peritoneum, often layered by tumor nodules, is firmly grasped using a Russian forceps and peeled away from the common bile duct and hepatic artery.

Resection of the Hepatogastric Ligament and Lesser Omentum

The left lateral segment of the liver is retracted left to right to expose the hepatogastric ligament in its entirety. A circumferential release of this ligament from the fissure between the left lateral portion of the liver and segment 1 occurs first. The arcade of right gastric artery to left gastric artery along the lesser curvature of the stomach must be skeletonized. After electrosurgically dividing the peritoneum on the lesser curvature of the stomach, digital dissection with extreme pressure from the surgeon’s thumb and index finger separates lesser omental fat and tumor from the vascular arcade. As much of the anterior vagus nerve is spared as is possible with patience and persistence. The tumor and fatty tissue surrounding the right and left gastric arteries are split away from the vascular arcade. In this manner the specimen is centralized over the major branches of the left gastric artery. With strong traction on the specimen, the lesser omentum is released from the left gastric artery and vein.

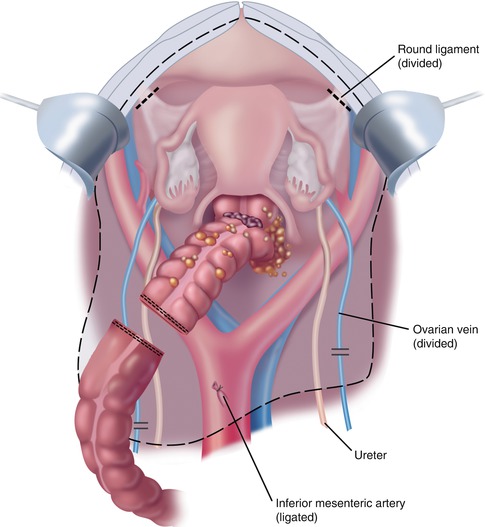

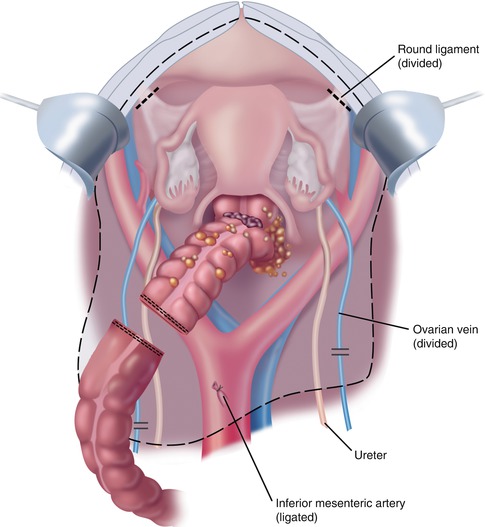

Resection of Rectosigmoid Colon, Uterus, Ovaries, and Cul-de-sac of Douglas

To being the rectosigmoid colon resection, a linear stapler is used to divide the sigmoid colon just above the limits of the pelvic tumor; this is usually at the junction of sigmoid and descending colon. The vascular supply of the distal portion of the bowel is traced back to its origin on the aorta. The inferior mesenteric artery and vein are ligated, suture ligated, and divided. This allows one to pack all the viscera, including the proximal descending colon into the upper abdomen.

Ball-tipped electrosurgery is used to dissect at the limits of the pelvic peritonectomy (Fig. 11.5). The surgeon works in a centripetal fashion. Extraperitoneal ligation of the uterine arteries is performed just above the ureter and close to the base of the bladder. In women, the bladder is moved gently off the cervix and the vagina is entered. The vaginal cuff anterior and posterior to the cervix is transected using ball-tipped electrosurgery, and the rectovaginal septum is entered. Ball-tipped electrosurgery is used to divide the perirectal fat beneath the peritoneal reflection. This ensures that all tumors that occupy the peritoneum within the cul-de-sac are removed intact with the specimen. The anterior rectal musculature is skeletonized using ball-tipped electrosurgery. Preservation of the lower half of the rectum will allow for a larger stool reservoir and diminish frequent bowel movements. A stapler is used to close off the rectal stump, and the rectum is sharply divided above the stapler.

Fig. 11.5

Rectosigmoi-dectomy and complete peritonectomy (From Sugarbaker PH. An overview of peritonectomy, visceral resections, and perioperative chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy. In: Sugarbaker PH. (ed.) Cytoreductive Surgery and Perioperative Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Surface Malignancy. Woodbury, CT: Textbook and Video Atlas. Cine-Med Publishing; 2012. pp. 1–30)

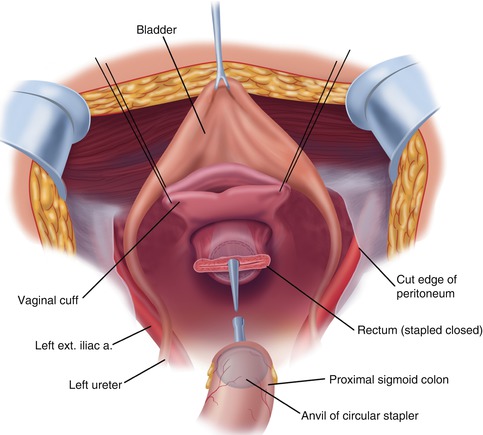

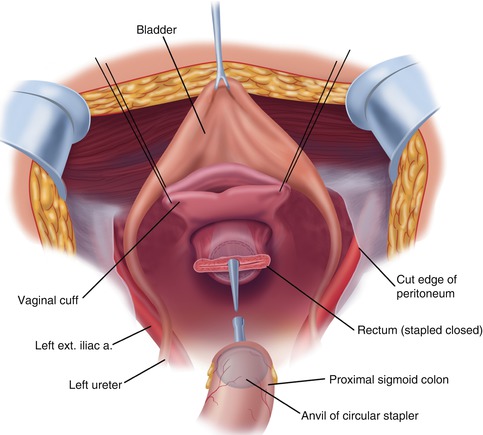

Secure Vaginal Closure and Colorectal Anastomosis

Additional sutures are placed to close the apex of the vagina (Fig. 11.6). These sutures are left long so that they may be used to elevate the vaginal cuff and clearly expose the stump of the rectum.

Fig. 11.6

Reconstruction after rectosigmoid colon resection and complete pelvic peritonectomy. The vagina is closed prior to the hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. The low-stapled colorectal anastomosis is performed after the chemotherapy lavage is complete (From Sugarbaker PH. An overview of peritonectomy, visceral resections, and perioperative chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy. In: Sugarbaker PH. (ed.) Cytoreductive Surgery and Perioperative Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Surface Malignancy. Woodbury, CT: Textbook and Video Atlas. Cine-Med Publishing; 2012. pp. 1–30)

Rationale for Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy and Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

After completion of the cytoreduction when no visible cancer remains, it is invariably true that invisible to the naked eye, an immense number of cancer cells will remain within the peritoneal cavity. Tumor manipulation, transected lymphatic ducts leaking tumor cells throughout the procedure, and small tumor nodules remaining on the abdominal and pelvic surfaces of organs not amenable to peritonectomy procedures, namely, small bowel, make necessary the implementation of some method that will eradicate residual tumor cells. Another well-known site for persistent disease is the suture lines that are an ideal site for cancer cell implants. Tumor cell entrapment occurs on these raw surfaces with fibrin accumulating and tissues compressed together by stitches or staples. Suture lines are at high risk for recurrence if constructed before the hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

Technique for Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

An abdominopelvic reservoir is constructed by tenting up the skin edges on a fixed retractor that allows hand distribution of the chemotherapy agent and total containment. The gloved hand guarantees that the perfusate reaches all surfaces within the peritoneal cavity, such as the space between the bowel loops, the space behind the liver, and the pelvic cavity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree