BACKGROUND

Diabetic nephropathy during pregnancy has been defined as a total urinary protein excretion of greater than or equal to 300 mg/24 h measured prior to pregnancy or greater than or equal to 300 – 500 mg/24 h measured prior to 20 weeks of gestation.1–6 Diabetic nephropathy is also defined as microalbuminuria (urinary albumin excretion of 30–299 mg/24 h) either prior to pregnancy or early in gestation.6–8 Incipient diabetic nephropathy is defined as either microalbuminuria (urinary albumin excretion of 30–299 mg/24h)7–10 or total protein excretion of 190 – 499 mg/24 h prior to 20 weeks of gestation.1,5 These differences in definitions (use of albuminuria or proteinuria) reflect the variation in methods used to measure protein excretion.

The term diabetic nephropathy during pregnancy also refers to an heterogenous group of women with either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes with or without significant derangement in renal function (creatinine clearance, serum creatinine, level of proteinuria) and a wide spectrum of BP values (normal, mild, moderate or severe hypertension). Thus, pregnant women with diabetic nephropathy may encompass subjects who have normal renal function (serum creatinine and creatinine clearance) and normal BP to those with endstage renal disease with severe hypertension, proliferative retinopathy, and ischemic cardiac changes.1–15 Consequently, pregnancy outcome as well as long-term prognosis will vary because of confusing terminology and nomenclature, as well as differing stages of nephropathy.

PREVALENCE

In the US, the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy in women is increasing because of the trend of increasing prevalence of Type 2 diabetes.3,16 The exact prevalence of diabetic nephropathy in pregnant women with diabetes is unknown. However, reports range from 5% to 10% of pregnancies complicated by diabetes mellitus.3,13 Prevalence rates vary with the diagnostic criteria used (depending on whether proteinuria or albuminuria was present prior to pregnancy or whether it was measured before 20 weeks of gestation).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

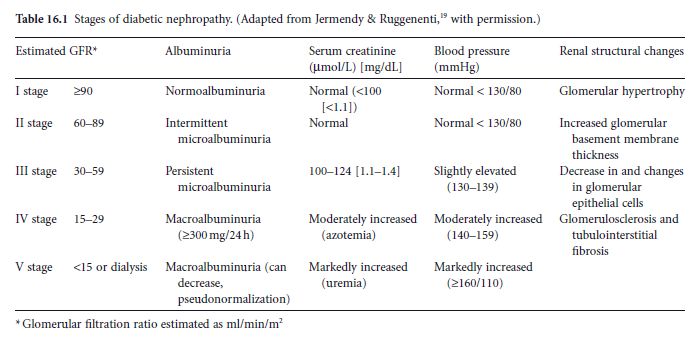

Diabetic nephropathy is one of the most common micro-vascular complications of diabetes and is the leading cause of renal failure in developed countries.17–19Nephropathy due to Type 2 diabetes accounts for the majority of patients with renal failure.17–19 The exact mechanisms by which diabetes induces nephropathy remain unclear; however, it has been suggested that diabetic nephropathy results from the interaction between genetic predisposition and certain environmental insults (both metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities) related to the diabetic state.17–19 Overt diabetic nephropathy is usually preceded by a long silent phase of glomerular changes (hypertrophy–hyperfunction, increased intraglomerular pressure) that is followed by incipient nephropathy with micro-albuminuria. It has been reported that the natural course of diabetic nephropathy has five stages which correlate with specific changes in glomerular anatomy, physiology, and renal function. In order of development these include:

These structural changes in the glomeruli ultimately occur concurrently with the renal functional changes described in Table 16.1.19

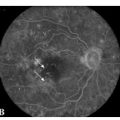

The natural history of nephropathy differs between patients with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. At the time of presentation, patients with Type 2 diabetes exhibit an increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and glomerular hypertrophy. Microalbuminuria is unusual during the first 5 years following diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes, whereas it is more likely to be present at diagnosis in Type 2 diabetes. However, approximately 20% of patients with Type 1 diabetes will develop microalbuminuria after 5–10 years. Overt nephropathy will subsequently develop within 5–10 years after the onset of microalbuminuria.6,16 This phase is usually characterized by a decrease in GFR, and a slight increase in serum creatinine and BP. The final stages are frequently associated with a progressive decline in renal function, severe hypertension, and ultimately development of endstage renal disease. It is important to emphasize that retinopathy is almost always present in patients with overt nephropathy, and is proliferative in 60–70% of cases.3,6

There are several factors that increase the risk of progression of nephropathy.17–19 Some of the factors studied include increased hyperfiltration, poor glycemic control, and hypertension. Consequently, several observational studies and randomized trials have evaluated the benefits of tight blood glucose control with insulin and diet and the use of medications that lower BP and intraglomerular pressure, such as ACE-Is and ARBs in ameliorating or preventing the development of nephropathy in patients with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. In general, these studies suggest that therapeutic intervention with ACE-Is for preventing diabetic nephropathy should ideally begin prior to the development of microalbuminuria.3,16–19 I n addition, they suggest that ACE-Is and ARBs are the drugs of choice to prevent and/or reduce the risks of progressive diabetic nephropathy.6,16–19

Table 16.1 Stages of diabetic nephropathy. (Adapted from Jermendy & Ruggenenti,19 with permission.)

SCREENING FOR NEPHROPATHY PRIOR TO CONCEPTION AND/OR IN EARLY PREGNANCY

Screening for microalbuminuria should ideally be per-formed in all women with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes prior to conception. There is no consensus regarding the method to be used for detecting microalbuminuria. Urinary excretion of albumin can be measured either by estimation of albumin-to-creatinine ratio in a random sample or a 24-hour urinary timed sample. There is a large intraindividual day-to-day variation in albumin excretion in diabetic patients. Therefore, repeated measurements are important to establish albuminuria. Although dipstick measurements of albuminuria are useful for screening purposes, they are not recommended to detect the presence or absence of microalbuminuria.19

Pregnancy in non-diabetic women is characterized by an increase in GFR and renal plasma flow. The increase in GFR begins very early in the first trimester,3 and thus may be confused with stage 1 diabetic nephropathy. As a result, serum creatinine values tend to be lower in normal pregnant women compared with non-pregnant values. The renovascular changes during pregnancy in patients with diabetic nephropathy are similar to those in patients with pre-existing renal disease. These changes will depend on the level of renal insufficiency prior to conception or early in pregnancy. Normal pregnancy is characterized by increased GFR, reaching about 50% above pre-pregnancy values by 18 weeks of gestation, a state of hyperfiltration and reduced serum creatinine (usually <71μmol/L [<0.8mg/dL]). In addition, there is an increase in protein excretion with advanced gestation; however, total protein excretion remains below 300mg/24h.3 Several studies have compared the value of urinary dipstick protein values and protein-to-creatinine ratios in random urine samples with 24-hour protein measurements in normotensive and hypertensive pregnancies. A recent systematic review suggested that in normal pregnancy urinary protein dipstick measurements did not correlate with quantitative timed collections.20 In addition, a systematic review of studies using protein-to-creatinine ratios to measure proteinuria also found that values of less than 130–150 mg of protein/g of creatinine were reliably able to rule out significant proteinuria (>300mg/24h), but values above this level were not able to quantitate pro-teinuria.21 Therefore, in pregnant women with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, 24-hour timed collections should be used to establish the presence of micro and macro-albuminuria and for the serial evaluation of protein excretion during pregnancy.

PREGNANCY OUTCOMES

There are numerous studies that have described pregnancy outcomes in patients with diabetic nephropathy. However, many of these have methodologic limitations. First, the majority of these studies are retrospective in design, of small sample size, usually performed at a single institution over a long period of time, and frequently there is inadequate control for confounding variables. Second, many of the studies lack detail about the presence or absence of associated comorbid conditions, as well as the degree of blood glucose and BP control prior to conception and during pregnancy. Third, in many of these reports, the diabetic patients under study are heterogenous with various degrees of renal impairment, protein excretion, and hypertension at the time of inclusion. Finally, the definition of maternal clinical outcomes, such as pre-eclampsia, deterioration in renal function, and fetal outcomes (congenital malformations, perinatal death, and preterm delivery) frequently differ among studies.

Nonetheless, the available literature clearly indicates the importance of maternal renal function and vascular status prior to conception in counseling these patients about the acute and long-term effects of pregnancy on maternal outcome.2–6,22 In addition, it emphasizes the importance of strict glycemic control and aggressive control of maternal hypertension on overall maternal and perinatal outcome.2–6,13,22

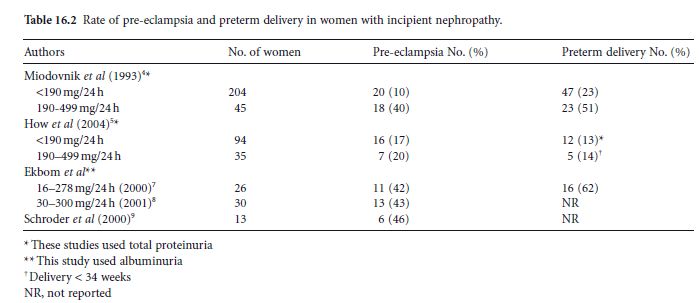

Incipient nephropathy

The rubric of incipient nephropathy in pregnancies complicated by diabetes with onset prior to conception and/ or early in gestation (before 20 weeks) includes women who had a normal serum creatinine and either micro-albuminuria (30–300 mg/24 h) or proteinuria (190–499 mg/24 h) before 20 weeks of gestation. Overall, those pregnancies associated with incipient nephropathy have increased rates of both preeclampsia and preterm delivery (Table 16.2).1,5,7–9 Data on pre-eclampsia need to be interpreted with caution (see below).

Overt nephropathy

During the past decade, there has been a significant improvement in maternal and perinatal outcomes of pregnancies complicated by diabetic nephropathy. This improved outcome has resulted from advances in BP control, intensive fetal monitoring, early hospitalization for control of pregnancy complications, timely deliver y,3,22 and advances in neonatal care. Nevertheless, pregnancies complicated by diabetic nephropathy are still associated with increased rates of cesarean section, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction (FGR), and perinatal mortality. The magnitude of these risks will depend on the appropriateness of management prior to conception and during pregnancy, the degree of abnormalities in renal function (serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, amount of proteinuria), and the presence or absence of associated vascular involvement (hypertension, retinopathy, cardiovascular dysfunction).3,22,23 In general, pregnancy outcome is usually favorable in patients with normal to minimal elevations in serum creatinine less than 124μmol/L (1.4 mg/dL), and/or proteinuria of less than 1 g/24 h, and/or normal BP, and/or absent proliferative retinopathy prior to conception or early in pregnancy.2–6,11–14 In contrast, maternal and perinatal outcomes are usually poor in patients with serum creatinine above 124μmol/L (> 1.4 mg/dL) and/or in those with severe hypertension, and/or nephrotic range proteinuria (≥3 g/24 h), and those with pre-existing cardiovascular disease.3,4,2223

Table 16.2 Rate of pre-eclampsia and preterm delivery in women with incipient nephropathy.

Pre-eclampsia is one of the most important and the major obstetric complication in patients with overt nephropathy. The diagnosis of pre-eclampsia can be difficult to make in the diabetic patient with pre-existing hypertension and proteinuria. General guidelines include:

- Pre-eclampsia in the woman with pregestational diabetes who is normotensive and non-proteinuric can be diagnosed after 20 weeks of gestation by a BP of greater than 140/90 mmHg associated with proteinuria of at least 300mg/24h11

- In diabetic women with hypertension but without baseline proteinuria, pre-eclampsia is diagnosed by the new onset of proteinuria (>300mg/24h)11

- If the patient is normotensive, but has proteinuria in early pregnancy, pre-eclampsia is diagnosed by the onset of hypertension or thrombocytopenia. In those diabetic patients with both proteinuria and hypertension prior to pregnancy or before 20 weeks of gestation, the presence of pre-eclampsia can be determined by new onset of thrombocytopenia, and/or a severe exacerbation of hypertension (systolic BP ≥ 160 and/or diastolic BP ≥ 110 mmHg) with exacerbation of proteinuria or symptoms (cerebral or visual).11

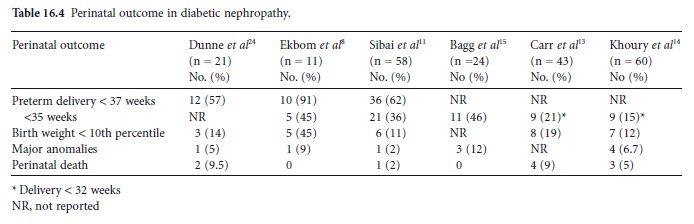

The above criteria are based on expert consensus opinion and were recommended by the National Working Group on Hypertension in Pregnancy as well as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.11The rate of pre-eclampsia in recently reported studies has ranged from 32 to 65% (Table 16.3).2,4,5,8,11–15,24 This variation in rate is likely due to differences in the study population demographics, presence and degree of nephropathy, sample size, as well as differences in criteria used to diagnose pre-eclampsia. Glycemic control is also thought to play a role in the development of pre-eclampsia. It is hypothesized that poor glycemic control leads to a restriction of the proliferation of cytotrophoblasts during the first trimester and to the decreased conversion of maternal spiral arteries to large sinusoidal vessels (see chapter 3). When this occurs, insufficient utero-placental circulation results. There are other adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients with diabetic nephropathy (Table 16.4).8,11,13–15,24 Again, the rate of these complications will depend on the degree of renal dysfunction and presence of associated comorbidities prior to conception.

Table 16.3 Rate of pre-eclampsia in women with overt diabetic nephropathy.

| Authors | No. of women | Pre-eclampsia No.(%) |

| Reece et al33 | 31 | 11(35) |

| Gordon et al2 | 45 | 24 (53) |

| Miodovnik et al4 | 46 | 30 (65) |

| How et al5 | 65 | 21 (32) |

| Khoury et al14 | 60 | 24 (40) |

| Sibai et al11 | 48 | 17 (36) |

| Ekbom et al8 | 11 | 7 (65) |

| Diabetes and Pregnancy Group12 | 41 | 21 (51) |

| B agg et al15 | 24 | 8 (33) |

| C arr et al13 | 43 | 15 (35) |

| Dunne et al24 | 21 | 11 (50) |

RISK ASSESSMENT AND PRECONCEPTION COUNSELING AND CARE

The first step in the management of a patient with diabetic nephropathy is to evaluate potential risk factors for adverse maternal and perinatal outcome. Several risk factors are recognized prior to conception that have been associated with an increased risk for poor outcome (Table 16.5). The magnitude of this risk will depend on the specific medical condition and its severity prior to conception. The presence of one or more of these risk factors will increase the likelihood that the patient will have superimposed pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, FGR, abruptio placentae, congenital malformations, perinatal death, and accelerated deterioration in renal function leading to endstage renal disease. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation prior to conception or early in pregnancy will help in appropriate counseling and in many instances, will allow for the implementation of targeted strategies to reduce the development of some of these complications.

Table 16.4 Perinatal outcome in diabetic nephropathy