BACKGROUND

Diabetic pregnancy continues to present a substantial risk for both mother and baby.1–4 Much of this risk occurs at the time of labor and delivery. This book has highlighted the critical role of optimal diabetes control and obstetric care prior to and during pregnancy in order to reduce and eliminate some of these adverse outcomes. Equally important is the management of diabetes in labor, delivery, and post delivery, and this should interface seamlessly with antenatal diabetes care. Poor or inappropriate diabetes management at this time can have major implications for the well-being of the mother and neonate. The focus of the physician caring for the diabetic woman during labor is to maintain normal maternal blood glucose levels in order to prevent maternal ketoacidosis, to avoid fetal acidemia with unnecessary intervention, and to reduce the risk of neonatal hypoglycemia with its subsequent separation of mother and baby.2 After delivery, regular diabetic supervision is required to ensure the stability of maternal glycemia in the face of changing insulin requirements. The postpartum period also provides a unique opportunity to influence behavior that may have significant implications for the long-term health of both mother and child.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In the normal pregnancy without diabetes, despite an increase in insulin resistance, blood glucose levels remain between 4.0mmol/L and 4.5mmol/L (72–81mg/dL). This corresponds to a doubling of insulin secretion by beta cells in the pancreas. Glucose passes from mother to fetus via facilitated diffusion, whereas insulin (unless antibody bound) does not cross the placenta at physiologic concentrations. In pregnancy complicated by Type 1 diabetes, the physiologic change in pancreatic beta cell function usually observed in normal pregnancy is impaired. The dose of insulin required tends to increase as the pregnancy progresses. This results from the physiologic increase in insulin resistance caused by maternal diabetogenic hormones, including increased free cortisol levels and the secretion of several pregnancy-related hormones, such as human placental lactogen. Under the Pedersen hypothesis,1 it is envisaged that maternal hyperglycemia promotes abnormal stimulation of the fetal pancreatic beta cells, resulting in marked fetal hyperinsulinemia. This mechanism can potentially explain many of the fetal complications seen during labor and delivery.

Type 2 and gestational diabetes are associated with both increased insulin resistance and abnormalities of insulin secretion (see chapter 2). During pregnancy, there is an increase in insulin resistance that facilitates growth and diversion of glucose to the fetus. In pregnancy complicated by Type 2 diabetes, the ability to increase insulin production via hypertrophy and hyperplasia of pancreatic beta cells is impaired.

LOCATION OF DELIVERY

It is recommended that pregnancy, labor, and delivery of women with pregestational and gestational diabetes should be supervised in centers with tertiary maternal and neonatal care, particularly in the US, where the levels of obstetric and neonatal care vary substantially from one hospital to the next. As there is a substantial risk of neonatal hypoglycemia and other complications, close monitoring and supervision are required. Although traditionally, many infants were admitted to a specialist neonatal unit, this is probably unnecessary in the majority of cases and should be reserved for standard peridelivery problems and/or for those babies suffering from significant neonatal hypoglycemia.2,4

PRETERM LABOR

Use of tocolytic agents and antenatal steroids

Preterm labor can be particularly hazardous for the infant of the diabetic mother. Beta-sympathomimetic agents, which may be used to suppress uterine contractions, are capable of causing rapid and extreme elevations in maternal glucose concentrations and possibly ketoacidosis. Corticosteroids, used to accelerate fetal lung maturation, may also result in significant and prolonged maternal hyperglycemia. During treatment with these drugs, regular diabetes supervision is essential. Maternal glucose should be carefully monitored, hourly if necessary, and 2–4 hourly once maternal glucose levels are stable. Even women with gestational diabetes may have their diabetes control worsened significantly; they must also have regular monitoring of their glucose levels and insulin may be required.

Various glucose/insulin algorithms involving increased insulin dosage have been described, and this requirement should be anticipated. We have successfully used an algorithm comprising additional doses of subcutaneous insulin during steroid treatment (intramuscular administration of betamethasone 12 mg repeated after 12 hours), aiming to maintain preprandial glucose levels below 6 mmol/L (< 108 mg/dL) without excessive hypoglycemia.5 This algorithm which is administered as an inpatient involves:

A broadly similar, although less aggressive, approach has been employed in Scandanavia.6 Another group7 reported its experience of a supplementary intravenous sliding scale (in addition to the woman’s usual subcutaneous insulin regime) to indicate the required dosage of insulin infusion in six women receiving antenatal steroids. The additional infusion was commenced immediately before the first steroid injection and continued until 12 hours after the second injection. Patients moved up to a higher level of insulin administration as dictated by glucose levels. Using this method, 75% of all glucose measurements were within 4–10mmol/L (72–180mg/ dL).

The UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH)2,3 highlighted that only 293 of 328 women giving birth before 34 weeks received a full course of antenatal steroids; the most common reason for non-administration was birth of the baby before the full course could be given.

Summary of recommendations

- When tocolysis is indicated in women with diabetes, an alternative to betamimetics should be used to avoid hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis.

- The use of antenatal steroids for fetal lung maturation with diabetes is associated with a significant worsening of glycemic control and this must be anticipated.

- Women with insulin-treated diabetes who are receiving steroids for fetal lung maturation should be closely monitored and receive supplementary insulin according to an agreed protocol.

- Further appraisal of the optimal methods to achieve euglycemia in this context is needed.

EVIDENCE IN SUPPORT OF THE NEED FOR GOOD GLUCOSE CONTROL DURING LABOR

Neonatal hypoglycemia

This is a relatively common complication following birth among infants of mothers with diabetes, with prevalence rates ranging from 10% to 60%.8–10 It is well recognized that blood glucose in the neonate tends to fall early after birth, reaching a nadir between 1 and 2 hours. This is an almost universal finding and is unlikely to be of pathologic significance. Subsequently, even in the absence of nutritional intake, blood glucose rises significantly by 3 hours of age. The diagnosis of hypoglycemia therefore requires the persistence of neonatal hypoglycemia beyond the first few hours of birth as these babies have failed to mount an appropriate lipolytic and ketogenic response. The aim is to minimize the incidence and severity of hypoglycemia (<2.6mmol/L [<47mg/dL]) by early feeding and careful monitoring. This level is not necessarily used to diagnose the condition, but does indicate the level at which further intervention may be required. This is based on a study which showed that adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes were associated with repeated values below this level.11 The presumptive mechanism is thought to be neonatal hyperinsulinism resulting from hyperglycemia during labor, although a persisting autonomous fetal insulin secretion may also occur earlier in pregnancy in poorly controlled maternal diabetes.12

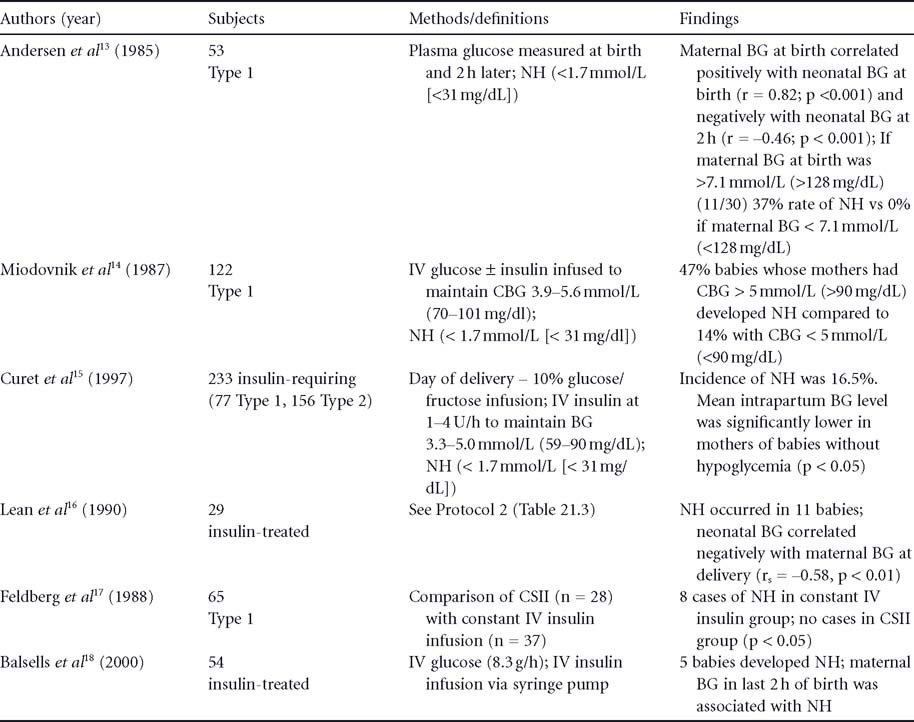

The results of a series of observational studies, summarized in Table 21.1 ,13–18 are in general agreement that neonatal hypoglycemia is closely related to maternal hyperglycemia in labor and during delivery. In addition, in a retrospective study involving 107 women with Type 1 diabetes, Taylor et al10 showed that neonatal hypoglycemia correlated with maternal hyperglycemia in labor, but not with HbA1c during pregnancy.

Fetal a cidemia

It has also long been recognized that maternal hyperglycemia is associated with an increased risk of fetal acidemia. Two observational studies in women with Type 1 diabetes considered the effect of intrapartum blood glucose control on fetal distress. In one study of 149 subjects,19 perinatal asphyxia was reported in 27% (n = 40). The maximum maternal blood glucose during labor was higher in babies with perinatal asphyxia than in those without (9.5 ± 3.7 vs 7.0 ± 3.0 mmol/L [171 ± 67 vs 126 ± 54mg/dL]; p < 0.0001). In the other study of 65 subjects,17 mean blood glucose during labor in women using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) (n = 28) was 4.8 ± 0.6 mmol/L (86 ± 11 mg/dL) (range 3.8–5.8 mmol/L) compared with 7.2 ± 1.1mmol/L (130 ± 20 mg/dL] (range 5.6–8.3 mmol/L) (p < 0.025) among those using a constant IV insulin infusion (n = 37). Acute fetal distress occurred in 27% of the IV infusion group versus 14.3% of the CSII group (p < 0.001); cesarean section occurred in 38% versus 25% (p < 0.05), respectively.

These data suggest that maintenance of maternal blood glucose between 4 and 7 mmol/L (72–126 mg/dL) during labor and delivery reduces the incidence of both neonatal hypoglycemia and “fetal distress”.4

Table21.1 Observational studies which have examined the relation between intrapartum capillary blood glucose (CBG) and neonatal hypoglycaemia (NH).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF GLYCEMIC CONTROL DURING LABOR AND DELIVERY

The main objective of glycemic control during labor is to avoid maternal hyperglycemia in order to minimize the risks of neonatal hypoglycemia and fetal acidemia as discussed above.

With elective cesarean delivery

- The physician (see below) responsible for care during labor should be informed of the admission.

- Women should ideally be first on the operating list.

- The mother should fast from 22.00h the previous evening (except for sips of water).

- The woman is allowed to take her long-acting insulin the preceding evening as usual, but does not take her usual insulin on the morning of delivery.

- A glucose/insulin infusion is begun 1–2 hours before surgery.

- Close liaison is required with the anesthesiologist (anesthetist).

- Maternal capillary blood glucose should be monitored hourly.

- The aim is to maintain blood glucose levels between 4 and 7mmol/L (72–126 mg/dL) according to protocol.

- The dose of insulin is adjusted in response to maternal capillary glucose.

In the UK, the physician is usually a diabetologist or internist specializing in diabetes, while the obstetrician manages the obstetric care and a neonatologist is present at delivery. In the US, it is more customary for the obstetrician in consultation with the perinatologist, the perinatologist exclusively, or the obstetrician in consultationwith both the perinatologist and endocrinologist (diabetologist), to manage all aspects of the patient’ s care during pregnancy, labor, and delivery

With induction of labor

- For standard induction with prostaglandins, women should continue to eat normally and to have their normal doses of insulin until in established labor.

- Once labor is established, a regime of IV dextrose/ insulin is commenced.

- Maternal capillary blood glucose should be monitored hourly.

- The aim is to maintain blood glucose levels between 4 and 7mmol/L (72–126mg/dL) according to protocol.

- The dose of insulin is adjusted in response to maternal capillary glucose.

With spontaneous labor

- The capillary glucose should be measured on admission and thereafter hourly.

- If the capillary glucose is between 4 and 7mmol/L (72–126 mg/dl) and delivery is imminent, hourly glucose measurement should be continued.

- If capillary glucose is greater than 7 mmol/L (>126mg/dL) or delivery is not imminent, an IV dextrose/insulin infusion should be commenced as per protocol.

- The subsequent steps are as for induction of labor (see above).

For mothers with gestational diabetes controlled on diet alone, maternal capillary blood glucose should be monitored every 1–2 hours once labor is established with the aim of keeping levels below 7 mmol/L (<126mg/dL). If this is not achieved, an insulin/dextrose infusion may be required. Women with gestational diabetes who required insulin during the course of their pregnancy should be treated as detailed for women who required insulin during pregnancy.

Women with Type 1 diabetes who use a CSII in pregnancy should have an agreed plan documented as to howblood glucose is to be achieved during labor and delivery. It is usually feasible to continue using CSII in labor and good results have been achieved. For example, in the study of Feldberg et al17 (see below), the insulin dosage was extended from pregnancy into labor and ranged between 0.5 and 1.2 U/h. However, delivery unit staff may have anxieties about this approach due to unfamiliarity, thus necessitating the close involvement of medicalpersonnel trained to adjust the CSII pump. Similarly,with cesarean section, anesthesiologists (anesthetists)may prefer to revert to an intravenous insulin regime.

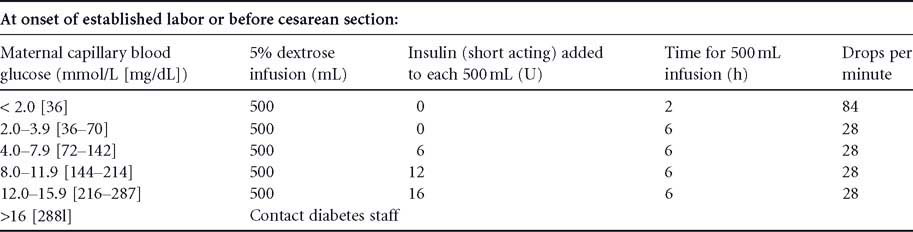

MATERNAL BLOOD GLUCOSE CONTROL DURING LABOR AND DELIVERY

There is no consensus over how best to achieve optimal maternal glucose control during labor and delivery. Perhaps the critical point is that the method of insulin delivery with which the physician and nursing staff are most familiar is the one which should be used. The first stage of labor is associated with a decrease in the need for insulin and a constant glucose requirement.20 Most of the data are observational and many regimes have arisen through personal experience. Details of three protocols are outlined by way of illustration. In Belfast, for many years we have successfully used an intravenous glucose/insulin infusion supplemented by additional insulin doses (Protocol 1; Table 21.2 ).21 Alternatively, some centers use a constant glucose infusion with insulin being infused separately by an infusion pump. The latter type of protocol was assessed during labor in 25 women with insulin-treated diabetes (Protocol 2; Table 21.3 )16. Blood glucose was maintained at 6.0 ± 1.8 mmol/L (108 ± 32mg/dL) for a mean of 6 hours before delivery. Neonatal hypoglycemia (plasma glucose <2.0 mmol/L [36mg/dL]) occurred in 11 (44%) babies. A further protocol was evaluated in terms of its ability to achieve normoglycemia during labor and delivery among 229 pregnancies in 174 women with Type 1 diabetes (Protocol 3; Table 21.4 ).22 Maternal glycemia during labor was 6.1 ± 1.6 mmol/L (110 ± 29 mg/dL) with a 13% incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia.

Feldberg et al17 in a small non-randomized trial of subjects with Type 1 diabetes, showed a significant decrease in neonatal hypoglycemia using CSII (maintained throughout gestation and delivery) (n = 28) compared with those using an IV regime (n = 39). Neonatal hypoglycemia occurred in 8% of infants in the IV insulin regime group and not at all in the CSII group; however, the subjects may have been self-selecting, leading to some bias. A randomized controlled trial23 examined the influence of rotating glucose-containing and glucose-free IV fluids versus an insulin infusion on intrapartum maternal glycemic control in women with insulin-requiring diabetes. There was no difference in mean maternal capillary blood g lucose levels in the two g roups (5.77 ± 0.48 mmol/L [104 ± 9 mg/dL] vs 5.73 ± 0.99 mmol/L [103 ± 18 mg/dL],

Table21.2 Protocol 1. (adapted from [21])