Diabetes Potpourri

Introduction

While we have tried to cover most of the common scenarios in diabetes care, there are still a few surprises. Here we discuss common but out-of-the-ordinary problems you may experience with your patients when providing diabetes care. Knowing to expect these will help you to be ready for the unexpected.

Case 1. Identifying Lipohypertrophy

“My insulin stopped working.”

A 64-year-old man presents for a diabetes recheck. He has had diabetes for 12 years. He is not sure what is going on. His medications used to work well but lately; his fasting glucose has been climbing. His morning glucose readings are usually around 160 to 240 mg/dL. He does not check his glucose later in the day.

Med HX: type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, degenerative joint disease in both knees, s/p bilateral knee replacement

Medications: metformin 1000 mg bid, insulin glargine 68 units per day, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, oral semaglutide 14 mg daily, valsartan/HCT 160/25 mg daily, diclofenac gel applied to each knee daily

Allergies: none

Family Medical History: family history (FH) of type 2 diabetes, hypertension (HTN)

Social History: lives with his spouse; retired janitor

Physical Exam: Ht. 5′7″, Wt. 197 lb, BMI 30.9, P 66, R 15 BP 142/84

GEN: obese male with truncal obesity in no distress

HEENT: normal including thyroid exam

CV: normal

RESP: normal

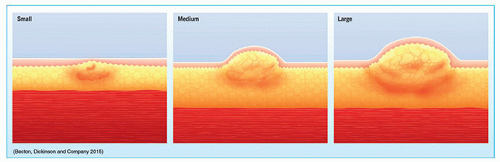

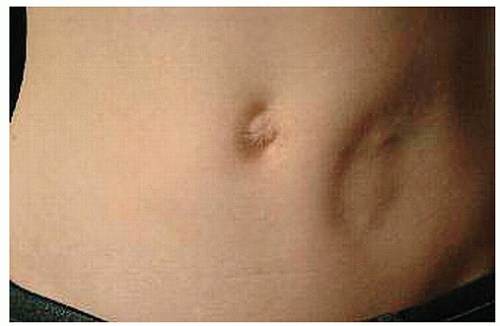

Abdomen: soft nontender, large area of scar tissue noted to the left and the right of the umbilicus (lipohypertrophy) (Figure 8.1)

Extremities: normal peripheral pulses, bunions noted to both great toes, sensation to monofilament exam is diminished in both distal feet

Labs:

HbA1c: 8.9%

Random glucose: 244 mg/dL (1:30 PM)

FIGURE 8.1. Image of lipohypertrophy. Mohammed SF, Kedir MS, Maru TT. (2015). Lipohypertrophy – The neglected area of concern in the much talked about diabetes. Int J Diabetes Res. 2015;4(2):38-42. doi:10.5923/j.diabetes.20150402.03.1 |

1. Is it possible that his insulin is not working?

View Answer

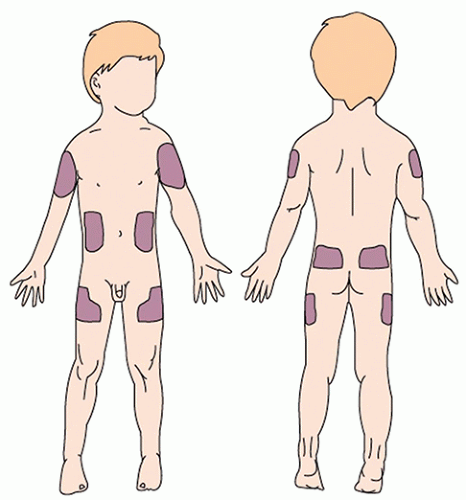

1. Yes, of course. Most of these causes are preventable. There are several things that affect insulin absorption and efficacy. The first thing to do when you hear this complaint is to look at the injection sites (Figure 8.2). Be sure to palpate the injection sites as well.

If the tissue is raised from scar tissue or there has been a loss of subcutaneous fat, this may affect insulin absorption. Further, people should only inject at sites that do not have scars (from previous surgery) or stretch marks, areas that do not have adequate subcutaneous fat, or areas that do not have enough vascular supply.

If there are no obvious problems with the injection sites, the next step is to ask the patient to demonstrate taking an injection of insulin. The goal is to confirm the proper insulin injection technique. Potential problems include not inserting the needle deep enough, injecting it into an area without enough vascular flow, or not operating the syringe or insulin pen accurately.

Finally, it is important to make sure that the insulin being used has not expired or denatured. We recommend that when a patient opens a pen or vial that they write the date opened on it with a sharpie. Most insulins are ok to use for 28 days after opening. While pens do not have to be refrigerated, it is important that the insulin not be exposed to extremes of temperature as this can denature or inactivate the insulin.

FIGURE 8.2. Potential injection sites. (Used with permission from Silbert-Flagg J. Maternal & Child Health Nursing. 9th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2022.)2 |

2. What is causing his insulin not to work?

View Answer

2. In this patient’s case, he has been injecting into the same spot for a long time and has, as a result, built up scar tissue. The term for this is lipohypertrophy. This scar tissue does not allow normal absorption of the injected insulin. Some people experience no noticeable insulin effects, while others will experience irregular absorption of insulin.

Best practices for people who have lipohypertrophy are to avoid this area for at least 3 months to allow for possible normalization of tissue.

3. What cutaneous reactions can occur with repeated insulin injections?

View Answer

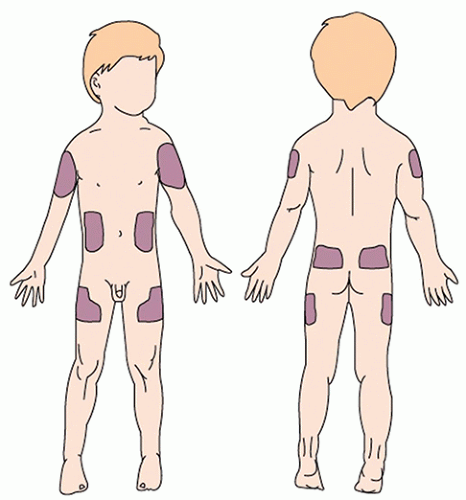

3. With proper injection techniques, these reactions can be largely prevented. However, you can see either a build-up of scar tissue (lipohypertrophy) (Figures 8.3 and 8.4A and B) or a breakdown of the subcutaneous fat (lipoatrophy)4 (Figure 8.5).

1. Yes, of course. Most of these causes are preventable. There are several things that affect insulin absorption and efficacy. The first thing to do when you hear this complaint is to look at the injection sites (Figure 8.2). Be sure to palpate the injection sites as well.

If the tissue is raised from scar tissue or there has been a loss of subcutaneous fat, this may affect insulin absorption. Further, people should only inject at sites that do not have scars (from previous surgery) or stretch marks, areas that do not have adequate subcutaneous fat, or areas that do not have enough vascular supply.

If there are no obvious problems with the injection sites, the next step is to ask the patient to demonstrate taking an injection of insulin. The goal is to confirm the proper insulin injection technique. Potential problems include not inserting the needle deep enough, injecting it into an area without enough vascular flow, or not operating the syringe or insulin pen accurately.

Finally, it is important to make sure that the insulin being used has not expired or denatured. We recommend that when a patient opens a pen or vial that they

write the date opened on it with a sharpie. Most insulins are ok to use for 28 days after opening. While pens do not have to be refrigerated, it is important that the insulin not be exposed to extremes of temperature as this can denature or inactivate the insulin.

write the date opened on it with a sharpie. Most insulins are ok to use for 28 days after opening. While pens do not have to be refrigerated, it is important that the insulin not be exposed to extremes of temperature as this can denature or inactivate the insulin.

FIGURE 8.2. Potential injection sites. (Used with permission from Silbert-Flagg J. Maternal & Child Health Nursing. 9th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2022.)2 |

2. In this patient’s case, he has been injecting into the same spot for a long time and has, as a result, built up scar tissue. The term for this is lipohypertrophy. This scar tissue does not allow normal absorption of the injected insulin. Some people experience no noticeable insulin effects, while others will experience irregular absorption of insulin.

Best practices for people who have lipohypertrophy are to avoid this area for at least 3 months to allow for possible normalization of tissue.

3. With proper injection techniques, these reactions can be largely prevented. However, you can see either a build-up of scar tissue (lipohypertrophy) (Figures 8.3 and 8.4A and B) or a breakdown of the subcutaneous fat (lipoatrophy)4 (Figure 8.5).

FIGURE 8.3. Lipohypertrophy. Venn-Wycherley A. Suspect, detect and protect: lessons from a lipohypertrophy workshop for children’s nurses. Nurs Child Young People. 2015;27(9):21-5. doi:10.7748/ncyp.27.9.21.s23.3 |

FIGURE 8.4. A and B, Insulin-medicated lipohypertrophy. A, Front view of Lipohypertrophy. B, Side view of Lipohypertrophy—you can see how area is raised. |

FIGURE 8.5. Lipoatrophy. (Used with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.)4 |

Case Summary and Closing Points

Improper insulin administration can affect a person’s glucose control. It is important to show your patients where they can safely inject their insulin and that they must rotate

or move sites regularly. When patients are injecting (insulin or other medications) they should avoid scar tissue, stretch marks, areas with little subcutaneous fat, and areas of low vascularity. Correct insulin techniques help patients receive the optimal and expected benefits from the medicine they are administering.

or move sites regularly. When patients are injecting (insulin or other medications) they should avoid scar tissue, stretch marks, areas with little subcutaneous fat, and areas of low vascularity. Correct insulin techniques help patients receive the optimal and expected benefits from the medicine they are administering.

References

1. Injection sites. https://mysteadyshot.com/pages/injection-sites (different -ok to use other version

2. Lipohypertrophy case.

3. Lipohypertrophy cartoon.

4. Babiker A, Datta V. Lipoatrophy with insulin analogues in type I diabetes. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:101-102.

Case 2. Glucose Testing and Diabetes Supply Snafus

“My friends say I have an A1c machine for home.”

A 48-year-old British man presents for a diabetes recheck. He has had diabetes for 8 years. He recently returned from a trip to England. Now, he reports that something is not “right” with his glucometer. Typically, he has been able to meet glucose goals. He knew that he would run higher during his vacation as he planned to enjoy all his favorite foods and beers. So, he took the precaution of visiting a local doctor during the visit. Since then, his readings have not made sense. He has been getting readings of 4.8 to 10.0.

When he returned to the United States, he showed his friend the meter he received from the English clinician. The friend said that the doctor had given him “one of those home A1c machines,” which he thought explained the low readings. The patient does not think the meter has been altered and is seeking confirmation.

Med HX: type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, depression

Medications: metformin 1000 mg bid, pioglitazone 30 mg daily, acarbose 50 mg tid qac, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, ramipril 5 mg daily

Allergies: none

Family Medical History: FH of type 2 diabetes, HTN, Alzheimer disease in mom

Social History: lives alone, author

Physical Exam: Ht. 5′9″, Wt. 193 lb, BMI 28.5, P 85, R 19, BP 136/80

GEN: obese male with truncal obesity in no distress

HEENT: normal including thyroid exam

CV: normal

RESP: normal

Abdomen: soft nontender, no masses

Extremities: normal peripheral pulses, normal sensation to monofilament exam to both distal feet

Labs:

Current A1c: 8.4%, last HbA1c 6 months ago was 7.1%.

Patient’s meter reading: 10.0

Office glucose reading: 180

1. What is the issue with his glucometer?

View Answer

1. The first thing to do is to examine the meter settings. Upon review, we discovered that the glucose units had been changed from mg/dL (US) to mmol/L (as used by most of the rest of the world). Since most people in the United States use imperial (or mass concentration) units, the metric (or molar) units for glucose will likely appear foreign. The good news is that it is easy to change the settings. Further, there is a simple conversion for switching between these units.

To get mg/dL (US) from mmol/L, multiply by 18. Conversely, to switch from mg/dL to mmol/L, divide by 18.

Our patient had a 10.0 mmol/L reading. We multiply the reading by 18 and determine that his US-based reading is 180 mg/dL.

2. What are other common problems with glucometers?

View Answer

2. Most people can work a glucometer without difficulty, yet some problems do arise. These include failing to change the settings with time changes that occur at daylight savings time. Most meters need to be set to the correct time and date or the data from the meters cannot be downloaded.

Another problem arises when users fail to test the meter with the control solution. All commercially approved meters must meet national standards for accuracy. However, there are some actions that can make the meter reading less accurate. All meters should be tested with a control solution with each new container of test strips. The control solution should also be refilled 90 days after opening. If the control solution is not used to calibrate the meter, the readings can drift.

Inaccurate readings can occur when users do not use clean hands when handling their meter. The correct technique is to clean and dry the testing site before performing glucose testing. A reading can be dramatically affected if obtained with unwashed hands.

Failing to use different sites for glucose checks can be problematic. If a person only uses one site for glucose monitoring, the skin can become callused and thickened (as discussed earlier), which may make it harder to test in that area in the future. Asking the patient to switch to new glucose monitoring sites will resolve this.

Finally, some people use an inadequate setting on the lancing device to get enough blood to test. When we are helping a patient with a new setup on a glucose measuring device, we explicitly show them how to adjust the lancing device depth. We usually advise patients to start with the middle setting and then show them how to adjust for comfort and efficacy.

3. What are common problems people have with supplies?

View Answer

3. One of the most common problems experienced by people with diabetes is not being able to get needed supplies. This is usually because the prescription was not written correctly, or the prescription did not have an ICD code attached. These and other common problems (and solutions) are listed in the following text.

1. The first thing to do is to examine the meter settings. Upon review, we discovered that the glucose units had been changed from mg/dL (US) to mmol/L (as used by most of the rest of the world). Since most people in the United States use imperial (or mass concentration) units, the metric (or molar) units for glucose will likely appear foreign. The good news is that it is easy to change the settings. Further, there is a simple conversion for switching between these units.

To get mg/dL (US) from mmol/L, multiply by 18. Conversely, to switch from mg/dL to mmol/L, divide by 18.

Our patient had a 10.0 mmol/L reading. We multiply the reading by 18 and determine that his US-based reading is 180 mg/dL.

2. Most people can work a glucometer without difficulty, yet some problems do arise. These include failing to change the settings with time changes that occur at daylight savings time. Most meters need to be set to the correct time and date or the data from the meters cannot be downloaded.

Another problem arises when users fail to test the meter with the control solution. All commercially approved meters must meet national standards for accuracy. However, there are some actions that can make the meter reading less accurate. All meters should be tested with a control solution with each new container of test strips. The control solution should also be refilled 90 days after opening. If the control solution is not used to calibrate the meter, the readings can drift.

Inaccurate readings can occur when users do not use clean hands when handling their meter. The correct technique is to clean and dry the testing site before performing glucose testing. A reading can be dramatically affected if obtained with unwashed hands.

Failing to use different sites for glucose checks can be problematic. If a person only uses one site for glucose monitoring, the skin can become callused and thickened (as discussed earlier), which may make it harder to test in that area

in the future. Asking the patient to switch to new glucose monitoring sites will resolve this.

in the future. Asking the patient to switch to new glucose monitoring sites will resolve this.

Finally, some people use an inadequate setting on the lancing device to get enough blood to test. When we are helping a patient with a new setup on a glucose measuring device, we explicitly show them how to adjust the lancing device depth. We usually advise patients to start with the middle setting and then show them how to adjust for comfort and efficacy.

3. One of the most common problems experienced by people with diabetes is not being able to get needed supplies. This is usually because the prescription was not written correctly, or the prescription did not have an ICD code attached. These and other common problems (and solutions) are listed in the following text.

Glucose Testing Supplies

When you write for these supplies, be sure to include, at a minimum, the lancets and glucose test strips. Ideally you are also writing for alcohol swabs to clean fingers. The number of each supply should match the number of glucose tests you are prescribing per day. Most of these supplies come in multiples of 25 or 50. Be sure to include a diagnosis code that supports the use of this equipment.

I write all testing supplies for 1 year. This allows the patient to have the supplies they need and reduces the number of random calls and requests for refills.

Sample RX

XX Brand Glucose test strips. #200. (3-month supply) Sig. fingerstick glucose 2 times per day. ICD code: E11.65, E16.2. 3 refills

XX Brand Lancets. #100. (3-month supply) Sig. fingerstick glucose 2 times per day. ICD code: E11.65, E16.2. 3 refills

Alcohol swabs #200. (3-month supply) Sig. fingerstick glucose 2 times per day. ICD code: E11.65, E16.2. 3 refills

Insulin Prescribing Problems

There are two common problems with insulin prescriptions. The first is not providing the needed tools to deliver insulin. If you are writing for insulin vials, you must also write for insulin syringes. Syringes come in three different volumes: 0.3 mL (holds up to 30 units), 0.5 mL (holds up to 50 units), and 1 mL (holds up to 100 units). It is important to make sure you provide a syringe that can hold the amount of insulin the person is supposed to inject. Otherwise, the person will need to take multiple injections for a single dose of insulin. The second issue is specifying what length needle you want on the syringe. To make things simple, I always use the shortest needles available on the insulin syringe and insulin pens. This is usually 5/32″ or 0.4 mm.

Sample RX

Insulin syringes 0.5 mL, #100 (1-month supply). Inject 35 units tid qac. E10.65, I10.

Additional problems include not writing for enough insulin for the given prescription or not providing the maximum daily dose if the insulin dose varies. It is important to write for the correct volume of insulin to match what the patient will be taking. Otherwise, they may run out of insulin early. This can result in gaps in medication, extra co-pays, and more trips to the pharmacy. To provide the correct volume of insulin, take the daily dose and multiply this by 30 or 90 days depending on the length of the prescription. Notice that we have included the ICD code as well in the prescriptions below.

Example: The patient is taking 50 units daily of insulin glargine by pen and insulin aspart 15 units per meal tid by pen. We want to provide him with a 3-month supply (90 days).

50 units/day × 90 days = 4500 units glargine.

You can write the quantity as units or you can convert it into volume. Pro-tip: Each pen holds 300 units, Therefore: 4500 units/300 units/pen = 15 pens.

For his mealtime insulin, he takes 15 units per meal. That is 45 units per day.

45 units/day × 90 days = 4050 units. Each pen has 300 units.

4050 units/300 units/pen = 13.5 pens. As you probably know we cannot prescribe ½ a pen. Pro-tip: Most insulin pens come in boxes of 5 so we will end up writing for 15 pens again.

The Prescription Would Look Like This

Insulin glargine U100. Dispense 45 pens (90 day supply). Take 50 units once daily in the evening. E11.65.

Insulin aspart. Dispense 45 pens (90 day supply). Take 15 units before each meal tid. E11.65.

Pen needles. Dispense: #400 (90 day supply). Inject insulin 4 times per day. E11.65.

One Last Insulin Issue

Many people who take mealtime insulin also take correction as part of their mealtime dose. This means that the dose may vary significantly from day to day. The pharmacy will share the directions for correction dosing, but the prescription must have a maximum daily dose to ensure an adequate supply. If the max daily dose is not on the prescription, the pharmacist will not know how much to dispense, and the prescription will be returned to the prescriber.

Let’s modify the prescription above for insulin aspart. This patient takes 15 units before each meal but also takes a correction dose if his glucose is high. The correction scale recommends to add 2 extra units for every 50 mg/dL the reading is above 150 mg/dL.

The Prescription Would Look Like This

Insulin aspart. Dispense 30 pens (90-day supply). Take 15 units before each meal tid plus 2 units for every 50 above 150. Max daily dose 90 units/day. E11.65.

Pen needles: 4 mm (nano) Dispense: #400 (90-day supply). Inject insulin 4 times per day. E11.65.

This may seem rather complicated the first few times you write these prescriptions. You will find, though, that the process does get easier with repetition and will eventually become second nature. Writing prescriptions well means fewer phone calls from the pharmacy.

Below are suggestions to make the calculation for insulin doses easier:

Pro-tips:

When writing for insulin pens, every 45 units taken daily requires 1 box of 5 pens per month.

For people who take insulin by vial, every 30 units taken daily requires 1 vial per month.

Write all testing supplies for 1 year. If done correctly, refills will be easy year after year.

Case Summary and Closing Points

The person with diabetes will need supplies to test their glucose and to take their insulin. These must be prescribed correctly to ensure uninterrupted access to those items needed for self-care. These simple steps can make all the difference in the world for your patients.

Case 3. Make a Sick Day Plan

“I do not know why I am running high.”

A 66-year-old man presents for an acute visit. He reports that normally his diabetes is well controlled, but he got gastroenteritis 2 days ago and he has been having nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea ever since. He was not eating and did not want to take his medications. He has been running very high and he is not sure what he should do. He has had diverticulitis before, and this can make him sick for about a week, but this is worse than that.

Normally his AM readings are 120 to 150 mg/dL and random glucose readings are 100 to 160 mg/dL. This week he has not been below 160 mg/dL and he is not eating.

Med HX: type 2 diabetes, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, dyslipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diverticulitis

Medications: metformin 1000 mg bid, glipizide 5 mg bid, canagliflozin 300 mg daily, simvastatin 40 mg daily, combivent 2 puff bid, amlodipine 5 mg daily, chlorthalidone 25 mg daily, omeprazole 40 mg daily

Allergies: none

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree