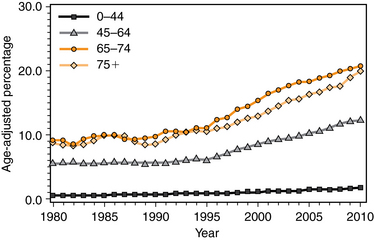

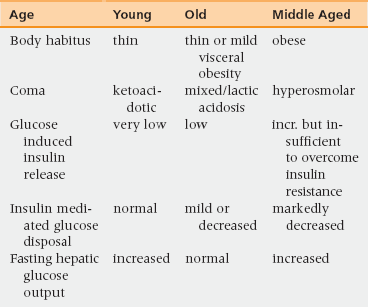

41 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Understand the changing epidemiology of adult diabetes mellitus (DM) and the impact it has on the elderly. • Identify the risk factors for DM in older persons. • Understand the continuum of the disease process in diabetes and how this affects the diagnostic criteria for DM. • Be able to assess the elderly diabetic in a multisystem and multidisciplinary fashion, including the common geriatric syndromes. • Describe the roles and contraindications for pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments of DM. The prevalence of diabetes continues to increase steadily in the general population with a peak occurring between 60 to 74 years of age (Figure 41-1). Between 1995 and 2007 diabetes mellitus in the nursing home increased from 16.9% to 32.8% of residents.1 Males tend to have a higher prevalence than females, and Hispanics and African Americans have a higher prevalence than whites. This increase in diabetes prevalence largely parallels the U.S. obesity epidemic. More than half of direct medical expenditures on diabetes are for those persons over 65. One dollar in every $10 spent on health care in the United States in 2002 was for diabetes. Nineteen percent of personal health care expenditures in the United States are for diabetes mellitus (DM), although only 4.2% of the U.S. population is known to have diabetes. Adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, people with diabetes had medical expenditures 2.4 times higher than those without diabetes.2 The life expectancy at birth of people with diabetes was 64.7 and 70.7 years for men and women, respectively, compared with 77.5 and 81.4 years in those without diabetes in a 2004 Ontario study.2 A British study of persons older than age 85 found that only 32% of the remaining life of persons with diabetes was active, whereas it was 42% for those without diabetes.3 Both an increased resistance to insulin-mediated glucose disposal and a decrease in non–insulin-mediated glucose uptake play a role in the development of diabetes mellitus in older persons.4,5 Both aging and obesity play a role in producing these effects. The resistance to insulin-mediated glucose disposal is, in part, caused by triglyceride infiltration into muscle and mitochondrial defects in the muscle. However, older persons with diabetes mellitus are much less likely to be obese than middle-aged people with the disease. In older persons a reduction in glucose-induced insulin release from the pancreas is a larger component of the pathophysiology than is seen in middle-aged persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Older persons have fewer abnormalities in fasting hepatic glucose output compared to middle-aged persons. The differences in how diabetes mellitus manifests in older persons compared to how it appears in “classical” manifestations are highlighted in Table 41-1. The renal threshold for glucose increases with age because older persons often have a higher thirst threshold; thus glycosuria may not occur.5 Polydipsia can be absent; presentation in the elderly may be dehydration with altered thirst perception and delayed fluid supplementation. Polyuria can present as incontinence. More often, changes such as dry eyes, dry mouth, confusion, incontinence, or diabetic complications are the presenting symptoms.6 Conversely, all elderly diabetics should be screened for these common syndromes within 3 to 6 months of diagnosis.7 The laboratory diagnosis, similar to the pathophysiology, involves a continuum from prediabetes to the diabetic threshold (Boxes 41-1 and 41-2). The fasting blood glucose (FBS) of 126 mg/dL or greater is still the preferred test to screen for prediabetes and diabetes.8 It is easily available, and has a 95% confidence interval (±18%) when performed on fasting venous plasma glucose samples (FPG).9 Older persons should be screened for DM annually; however, up to 30% of the diabetic elderly have an FBS of less than 126 mg/dL yet have a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of more than 200 mg/dL.8 The vast majority of those who meet the OGTT criteria for diabetes, but not the FBS criteria, will have an HbA1C less than 7.0%. 1. Macrovascular complications of coronary, carotid, and peripheral atherosclerosis (patient interviews should focus on neurologic symptoms, syncope, chest pain—often atypical, exertional dyspnea or fatigue, and claudication); lipid profile and liver function tests and electrocardiogram are appropriate. However, there is limited evidence in support of treating hyperlipidemia in persons older than 75 years of age who have not had a recent myocardial infarction or stroke. There is no evidence to use high doses of statins. 2. A new systolic blood pressure goal of 140 or lower has been set for people with hypertension as well as diabetes. (A lower systolic target of 130 is to be considered in some individuals, such as younger people.) Blood pressure should be measured when not at the physician’s office because “white coat” hypertension occurs in 25% of patients. 3. Microvascular renal complications are assessed by urinalysis, urinary microalbumin, and serum creatinine. 4. Retinal complications require an ophthalmologist for dilated retinal examination; glaucoma and cataracts should also be included in the screening. 5. Foot complications and vulnerability should be assessed at every visit. Neuropathy should be assessed by a monofilament test and examination for posterior column disease. If a posterior column is present then a vitamin B12 test should be obtained. 6. Screening for mood and cognition should be considered annually (because of increased depression and dementia). 7. HbA1C should be assessed at the time of diagnosis and every 3 to 6 months thereafter because average blood glucose levels and microvascular complications are significantly related. 8. All diabetics need to have postural hypotension measured at every visit. Persons who complain of dizziness or falling within 2 hours of a meal should be screened for postprandial hypotension, which is present in 20% of patients with diabetes.

Diabetes mellitus

Prevalence and impact

Pathophysiology

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Presenting symptoms

Screening for and confirming the diagnosis

Diabetes mellitus