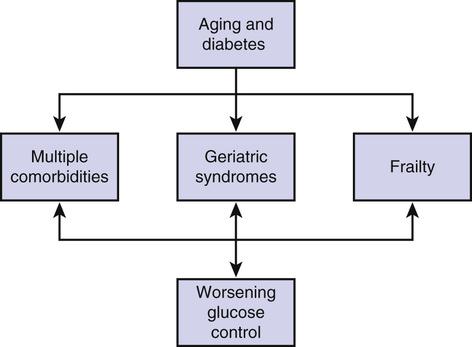

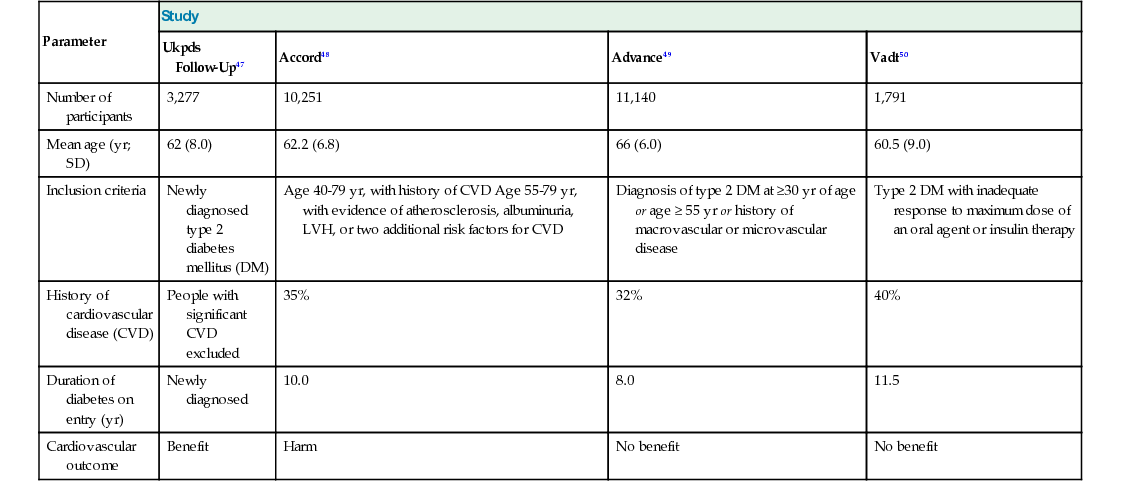

Alan J. Sinclair, Ahmed H. Abdelhafiz, John E. Morley With increasing aging of the population and urbanization of lifestyle, the prevalence of diabetes has or is likely to reach epidemic levels in most countries, especially in adults older than 75 years.1 Aging is associated with body composition changes that lead to increased insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and increased risk of diabetes.2 As a result, more older adults are developing diabetes. The lifetime risk of developing diabetes is high, reaching 22.4% for women and 18.9% for men from the age of 60 years onward.3 Older adults with diabetes are exposed to the interplay among metabolic dysfunction, vascular disease, and the aging process in combination with other age-related disorders. Geriatric syndromes and frailty have been emerging as a third category of complications, in addition to the traditional microvascular and macrovascular diseases.4 Therefore, diabetes in older adults may lead to considerable disability. Unlike other chronic conditions, diabetes care is dependent on self-management, which may be compromised by the presence of comorbidities and geriatric syndromes. Owing to the heterogeneous nature and variations in comorbidity, life expectancy, and functional status, ranging from a fit individual living independently in the community to a fully dependent person living in a nursing home, therapeutic interventions and metabolic targets should be individualized, taking into consideration individual preference while putting quality of life as the basis of care plans. This chapter reviews the phenotype of diabetes in old age and addresses the key areas and special considerations for the care of older adults with diabetes to meet their complex needs. The prevalence of diabetes rises with increasing age. Worldwide, the greatest proportional increase in the number of people with diabetes by age group is expected to occur in people aged 60 to 79 years. 3 For example, in France, the prevalence has increased to 14.2% in those aged 65 to 74 years, peaking at 19.7% in men and 14.2% in women aged 75 to 79 years. More than 50% of those with diabetes were older than 65 years.5 In the United States, 14% of the population is estimated to have diabetes, and the prevalence is highest in those older than 65 years; by 2050, diabetes prevalence could be as high as 33% of the whole population.6 However, a similar number may remain undiagnosed. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in those older than 75 years was 14.9%, and the prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes based on fasting plasma glucose level and 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test was 13.4%. This is a total prevalence of diabetes of 28.3%, with undiagnosed diabetes constituting around 47%. The prevalence of so-called prediabetes, defined as impaired fasting glycemia (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), was 46.7% in those older than 75 years. Therefore, the total prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes was approximately 75% in those older than 75 years.1 Low- and middle-income countries will have the greatest burden of diabetes, in which the prevalence will increase in adults aged 20 to 79 years by 69% by 2030 compared to only 20% in higher income countries.7 This is likely driven by the growth and aging of the population and urbanization of lifestyle in these countries. The prevalence of diabetes among older Chinese in rural Taiwan aged 72.6 years was 16.9% in 2000 and increased to 23.7% in 2005.8 In minority ethnic groups living in high-income countries, the incidence and prevalence of diabetes are higher than in white populations. For example, the prevalence of diabetes in older Mexican Americans (≥75 years) almost doubled from 1993 to 1994 and 2004 to 2005 from 20.3% to 37.2% in comparison to an increase from 10.4% to 16.4% in the general population of the same age.9 Diabetes prevalence in nursing homes is also high. Of U.S. nursing home residents in 2004, 24.6% had diabetes; among residents aged 65 to 74, 75 to 84, and 85 years and older, the prevalence of diabetes was 36.1%, 29.5%, and 18.3%, respectively.10 The prevalence of diabetes steadily increased in U.S. nursing homes between 1995 and 2004—16.9% to 26.4% in men and 16.1% to 22.2% in women. A more recent survey has shown a further increase in the prevalence of diabetes, with 32.8% of residents living with diabetes.11 Ethnic disparities in diabetes prevalence have also been well documented in care home settings. In U.S. nursing homes, the adjusted odds of diabetes are approximately twofold higher in African American and Hispanic residents relative to white residents, with diabetes present in 22.5% of whites and in 35.6% of those from other ethnic groups.10 Glucose homeostasis requires normal insulin secretion by the pancreatic beta cells and normal glucose utilization by the peripheral tissues that are sensitive to insulin. Diabetes in older adults is linked to increased insulin resistance and decreased insulin secretion, with a principal defect of insulin resistance in obese individuals and insulin secretion in lean ones. It is likely that genetic and environmental factors are involved in the pathogenesis of insulin secretory dysfunction and insulin resistance. Because older adults are heterogeneous, the extent and rate of deterioration in glucose homeostasis are variable, leading to insignificant changes in some individuals and diabetes in others (Box 90-1). Aging is associated with body composition changes that result in increased insulin resistance.12 Increased visceral fat is associated with increased rates of lipolysis causing high levels of free fatty acids, which may have a role in reducing peripheral insulin sensitivity.13 Reduction of muscle mass or sarcopenia occurs with aging through physical inactivity and, because the muscle is the main site of glucose consumption, the loss of muscle mass increases insulin resistance.12 Accumulation of lipids within the muscles is another factor reducing insulin sensitivity. A reduction in mitochondrial function14 may also contribute to age-related glucose intolerance by reducing oxidative metabolism, physical fitness, and oxidative capacity. Low concentrations of adiponectin, leptin, and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and high concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are associated with aging and have been linked to increased insulin resistance and incident diabetes.14–16 Insulin secretion diminishes by 0.7%/year with increasing age because of reduced function and increased apoptosis of pancreatic beta cells.17 Beta cell autoimmunity may lead to the activation of an acute-phase response in older adults with diabetes, with hypersecretion of interleukins, C-reactive protein, and TNF-α, which may reduce insulin secretion.18 Disturbances in the physiology of the gut-derived incretins, gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), may be another factor involved in beta cell dysfunction.19 Both peptides enhance insulin secretion after meals and may have a role in maintaining beta cell growth, proliferation, and inhibition of apoptosis. Aging is associated with reduced levels and function of these peptides.20 Diabetes in older adults is associated with coexistent multiple comorbidity burden, geriatric syndromes, and frailty (Box 90-2). Diabetes in older adults is associated with increased atherosclerosis, premature aging, and increased disability. Older adults with diabetes frequently have at least one comorbid chronic disease in addition to diabetes, and as many as 40% have at least three conditions.21 The comorbidity burden is even higher in nursing home residents with diabetes. For example, those with diabetes have more cardiovascular disease, visual problems, pressure sores, limb amputations, and kidney failure than residents without diabetes.22 In a retrospective case review of 75 U.K. nursing home residents with diabetes, significant levels of disability were shown in areas of continence, feeding, mobility, and communication. The average number of comorbidities per individual was four (range, one to eight).23 The mortality rate was 34% after 1 year of follow-up, indicating severe comorbidity.24 In another study, residents with diabetes had a greater comorbidity burden (hierarchic condition category, 1.90 vs. 1.58), used more prescribed medications, and experienced more hospitalizations than residents without diabetes (37% vs. 18%).11 Geriatric syndromes, such as cognitive and physical dysfunction, depression, falls, and urinary incontinence, are common in older adults with diabetes and may have subtle presentations.25 Diabetes is associated with a twofold increased risk of being unable to perform daily physical tasks, such as walking, doing housework, or climbing stairs, and a 1.6-fold greater risk of difficulties performing basic personal care, such as bathing, using the toilet, dressing, and eating. Diabetes complications, such as neuropathy, arthritis, and vascular disease, are contributors to physical disability in older adults with diabetes.26,27 The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures report28 has shown that diabetes also increases the risk of falls (odds ratio [OR], 2.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.82 to 4.25). A history of arthritis, musculoskeletal pain, depression, poor vision, and peripheral neuropathy are the main predictors of falling among older adults with diabetes.28 The risk of developing Alzheimer disease or vascular dementia is twofold higher in older adults with diabetes compared to age-matched adults without diabetes.29 In the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study, older adults (70 to 79 years old) with diabetes had an increased incidence of depression compared with persons without diabetes (23.5% vs. 19.0%; hazard ratio [HR], 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.61).30 Frailty is a condition characterized by a reduction in physiologic reserve and the ability to resist physical or psychological stressors.31 Its definition is largely based on the presence of three or more phenotypes (e.g., weight loss, weakness, decreased physical activity, exhaustion, slow gait speed).32 Frailty is viewed as a wasting disease, with weight loss being one of its criteria. Undernutrition, which is common in older adults, seems to be a risk factor for frailty. In the United States, about 16% of older adults living in the community are undernourished. These figures rise to 59% in long-term care institutions and to 65% in acute-care hospitals.33 Sarcopenia—muscle mass loss—is a component of frailty, which seems to be accelerated when diabetes is present. In a community study of 3153 participants older than 65 years, appendicular lean mass loss in men with diabetes was twice that of men without diabetes (3.0% vs. 1.5%) and, in women with diabetes, was 1.8 times that of those without diabetes (3.4% vs. 1.9%) over 4 years of follow-up. The mechanisms explaining these results may be related to reduced muscle protein synthesis as a result of lower testosterone and IGF-1 levels and increased muscle protein breakdown caused by a higher rate of inflammation.34 Diabetes also causes sarcopenia through the catabolic effect of insulin deficiency and by increasing intramyocellular lipid accumulation.35 In another study, older adults with type 2 diabetes had accelerated declines in leg lean mass, muscle strength, and longer sit-to-stand time compared to those with normoglycemia.36 Another factor related to malnutrition and frailty may be oral health. For example, optimal nutrition may not be maintained because of poor dentition, dry mouth, reduced taste sensation, palatability, and appetite change with increasing age.37 Diabetes can be asymptomatic in up to 50% of older adults.38 However, when symptoms are present, they are mostly nonspecific and may be attributed to aging. Nonspecific symptoms, such as general malaise, fatigue, or lethargy, are common manifestation of diabetes in older adults. Geriatric syndromes, such as falls and urinary incontinence, may be the first manifestation of diabetes. Symptoms may be atypical—for example, anorexia rather than the typical polyphagia. The classic osmotic symptoms are usually less prominent because of the increased renal threshold for glucose, reducing the intensity of polyuria, and impairment of thirst sensation, reducing the intensity of polydipsia. A hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state may be the presenting symptom, or diabetes may first be diagnosed during an acute illness or following a routine blood test (Box 90-3). The diagnostic criteria for diabetes are the same, irrespective of age. Clinicians should be aware that the fasting glucose concentration may be normal in the early stages of diabetes and is therefore less sensitive in diagnosing diabetes in older adults; however, the 2-hour glucose tolerance test appears to capture undiagnosed cases.9 Since February 2011, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) has been used as a diagnostic test for diabetes. However, although HbA1c has high specificity (98.7%), its low sensitivity (46.8%) means that it can miss more than 50%of people with diabetes.40 There are a number of pitfalls to using HbA1c in older adults. The HbA1c level increases with age after adjustment for glucose, suggesting that nonglycemic factors contribute to this increase. Furthermore, iron deficiency anemia, which is common in older adults, is associated with an increase in the HbA1c level independent of changes in the blood glucose level. Both these factors will lead to an overdiagnosis of diabetes in older adults if the HbA1c level is used instead of the glucose level. The diagnosis should be confirmed by a second laboratory test in the absence of diabetes symptoms, as for younger people. The phenotype of diabetes in older adults is highly variable and is affected by comorbidity, geriatric syndromes, and frailty. Therefore, diabetes management should take into account the heterogeneous nature of the diabetes and complex needs of the individual. A comprehensive geriatric assessment should be performed after the initial diagnosis and then annually because age-related comorbidities may impair diabetes control (Figure 90-1) Hyperglycemia should not be treated in isolation but as part of a multifactorial intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk. Cardiovascular complications remain the main cause of mortality, accounting for 50% to 75% of all deaths in people with diabetes.41 Management includes lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic interventions for hyperglycemia and cardiovascular risk factors (Box 90-4). Lifestyle modifications include changes in diet, weight reduction, smoking cessation (the single most effective means of reducing mortality42), and regular exercise to reduce visceral obesity and improve insulin sensitivity. Aging is associated with increased insulin resistance through the loss of skeletal muscle mass.12 Muscle mass is dependent on a balance between muscle protein synthesis and breakdown; protein intake with exercise training synergistically increases skeletal muscle mass in older adults. In one trial, protein supplementation for frail older adults who were engaged in resistance training resulted in muscle hypertrophy and increases in muscle strength, muscle mass, and performance.43 A diet that is high in fiber and potassium and low in saturated fats and refined carbohydrates and salt may help achieve an ideal body weight and improve the lipid profile, significantly lowering blood pressure and reducing the overall cardiovascular risk.44 In the Diabetes Prevention Program, lifestyle interventions, including modest weight reduction, healthy low-fat diet, and regular exercise reduced the development of diabetes; this beneficial effect persisted for up to 10 years after the end of the study, especially in older adults (≥60 years).45 Additional benefits of exercise for older adults may include increased muscle strength and improved walking balance. The Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study in middle-aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes has shown that weight loss and improved fitness lower the risk of loss of mobility.46 Although the evidence for reducing microvascular disease by tight glycemic control has been established, there is ongoing debate about whether reducing blood glucose to near-normal levels results in a lower incidence of cardiovascular events (Table 90-1).47–50 In frail older adults, the benefit of blood glucose control diminishes in the presence of other comorbidities. In a decision analysis to assess the effects of baseline health status on prioritization of therapy, blood pressure control conferred a larger benefit than glucose control for older adults (75 to 79 years), and the expected benefits of both therapies steadily declined as the level of comorbidity and functional impairment increased.51 Therefore, in older adults who are frail, with multiple comorbidities and functional impairment, tight control may be more harmful by inducing hypoglycemia. It is important to address individual goals of therapy, guided by patient preferences, life expectancy, comorbidities, and influences of therapy on quality of life. The advantages and disadvantages of hypoglycemic medications in older adults with diabetes are detailed in Table 90-2. TABLE 90-1 Summary of Key Studies of Glucose Control in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus TABLE 90-2 Hypoglycemic Medications for Older Adults with Diabetes: Key Messages A target systolic blood pressure of about 140 mm Hg is reasonable in older adults with diabetes because maintenance of a systolic pressure between 130 and 140 mm Hg is associated with a reduction of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in older adults with hypertension and diabetes. Tighter control, however, is not warranted, because this may be associated with increased adverse events. In the International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril (INVEST) Study, controlling systolic blood pressure to less than 130 mm Hg was not associated with better cardiovascular outcomes than usual control of 130 to 140 mm Hg in individuals 55 years of age and older, and it was associated with a nonsignificant increased risk of mortality (11.0% vs. 10.2%; adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.20; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99 to 1.45; P = .06).52 Tight blood pressure control (target < 120 mm Hg systolic) was also not beneficial and was associated with adverse outcomes in older adults (40 to 79 years) with diabetes.53 The Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET) also had similar conclusions for older adults, mean age 66 ± 7 years, of whom 57% were older than 65 years.54 Two meta-analyses of older adults with diabetes did not show reduced myocardial infarction or mortality rates with a systolic blood blood pressure less than 140 mm Hg.55,56 In much older adults (>80 years), the targets may be even more relaxed. The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET), which included older adults older than 80 years, with sustained systolic blood pressure higher than 180 mm Hg, 7% of whom had diabetes, showed a significant 33.7% reduction in cardiovascular events (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53 to 0.82; P < .001), with a target blood pressure control of 150/80 mm Hg. However, the individuals included in the HYVET study were healthier than those in the general population, with a low baseline rate of known cardiovascular disease (CVD; 11.5%), myocardial infarction (3.1%), and heart failure (2.9%). Therefore, the results may not apply to all older adults, especially those with multiple comorbidities or living in nursing homes.57 In another community study of people older than 85 years, there was a U-shaped relationship, with a systolic blood pressure of 164.2 mm Hg (95% CI, 154.1 to 183.8 mm Hg) being associated with the lowest mortality suggesting that the optimal systolic blood pressure for this age group could be more than 140 mm Hg.58 Thiazide diuretics, angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers are reasonable first-choice agents although higher doses of diuretics may worsen blood glucose levels and the lipid profile. Most people will require more than one antihypertensive agent.

Diabetes Mellitus

Introduction and Background

Epidemiology

Pathologic Process

Rise in Insulin Resistance

Fall in Insulin Secretion

Diabetes Phenotype in Old Age

Comorbidity Impact

Geriatric Syndromes

Frailty

Clinical Manifestations of Disease

Diagnosis

Treatment and Other Management Aspects

Lifestyle Changes

Hyperglycemia

Parameter

Study

Ukpds

Follow-Up47

Accord48

Advance49

Vadt50

Number of participants

3,277

10,251

11,140

1,791

Mean age (yr; SD)

62 (8.0)

62.2 (6.8)

66 (6.0)

60.5 (9.0)

Inclusion criteria

Newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM)

Age 40-79 yr, with history of CVD Age 55-79 yr, with evidence of atherosclerosis, albuminuria, LVH, or two additional risk factors for CVD

Diagnosis of type 2 DM at ≥30 yr of age or age ≥ 55 yr or history of macrovascular or microvascular disease

Type 2 DM with inadequate response to maximum dose of an oral agent or insulin therapy

History of cardiovascular disease (CVD)

People with significant CVD excluded

35%

32%

40%

Duration of diabetes on entry (yr)

Newly diagnosed

10.0

8.0

11.5

Cardiovascular outcome

Benefit

Harm

No benefit

No benefit

Medication

Advantages

Disadvantages

Sulfonylureas

Suitable for those with renal impairment or less risk of hypoglycemia

Increased risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain; long-acting sulfonylureas should be avoided.

Metformin

Less risk of hypoglycemia, cardiovascular benefit, weight neutral

Increased risk of lactic acidosis in those with renal impairment, heart failure, sepsis, and dehydration

Meglitinides

Short-acting, suitable for those with erratic eating pattern

Risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain but less than sulfonylureas

α-Glucosidase inhibitors

Less risk of weight gain and hypoglycemia

Weak hypoglycemic action, gastrointestinal side effects

Pioglitazone

Suitable for those with renal impairment or less risk of hypoglycemia

Fluid retention, worsens heart failure, increases fracture risk, possibly bladder cancer

DPP-4 inhibitors

Low risk of hypoglycemia, weight loss

Gastrointestinal side effects, dose mostly needs to be adjusted with renal impairment

GLP-1 receptor analogues

Low risk of hypoglycemia, weight loss

Injectable, weight loss in frail individuals, not suitable in renal failure, nausea , possible risk of pancreatitis

Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors

Low risk of hypoglycemia, weight loss

Not suitable for frail older adults with weight loss; heavy glucosuria increases risk of urinary tract infections, candidiasis, dehydration, and hypotension

Insulin

Effective, tailored rapidly to changes in need, improves quality of life

High risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain

Hypertension

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Diabetes Mellitus

90