Core Activities of an IP Program

The core activities of any IP program include healthcareassociated infection (HAI) surveillance, meeting accreditation requirements and public reporting, acute event response, performance improvement, and education and training.

2 When creating a new program or assessing an existing program, priorities should be grounded in these core activities in order to ensure that the basic functions and regulatory requirements for IP are met.

IP Program Reporting Structure

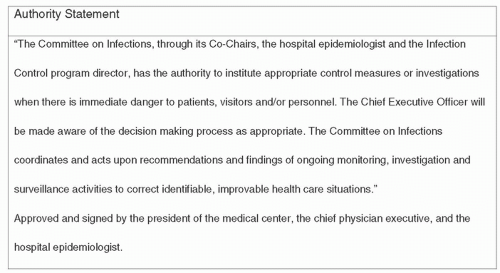

A formal reporting structure provides the hierarchical decision-making and communication pathway for the IP program. There are many reporting models in IP, and the

decision about which to choose can have profound impact on the structure, function, and funding of a program. The traditional reporting structure is one in which the IP program reports to a clinical division or department such as the Infectious Disease Division or Nursing. This reporting structure has the benefit of aligning the IP program with clinicians; however, this often creates a silo that prohibits the program from expansion of ideas and influence in the organization. This type of reporting structure categorizes IP along with direct clinical services and not with other integral support services in the organization such as engineering or environmental services. Examples of reporting structures that are more broadly aligned include those in which IP reports to the Risk Management division, the Healthcare Quality division, the Patient Safety division, or the Chief Medical Officer (CMO). These reporting structures demonstrate a broader conceptualization of the role that the IP program plays, categorizes the program as an essential patient safety activity in the organization, and provides greater access for the IP program to operational leaders.

Personnel

The most important part of an IP program’s infrastructure is its personnel. Determining each staff member’s preparation for their role and their ongoing education is essential for the success of the overall program. Background knowledge of microbiology, public health, nursing, or medicine is essential to lay the groundwork for building an individual’s ability to function and succeed in the day-to-day operation of the program.

The core staff members within an IP program are infection control and prevention practitioners, also called “infection preventionists”, who may have a background in nursing, microbiology, or public health. The skills and competencies required to practice IP are outlined by the Association of Professionals in Infection Control and Prevention (APIC).

4 Within the field of IP, APIC has described several levels of expertise. These progress from “novice” to “proficient” to “expert” and describe the knowledge and characteristics along with professional activities pertaining to each level. A successful IP should have knowledge of and engage in several practice areas including surveillance and epidemiology of infections, education of provider and ancillary staff along with patients and families, collaboration and consultation to build consensus for IP activities, program management and performance improvement, leadership, and implementation science and research.

Membership in a professional organization expands the ability to receive current literature on evidence-based practices, studies of current problems, and solutions in other programs and care settings. Professional organizations provide the opportunity to network with experienced and related institutional peers to gain knowledge and experience.

The optimum number of IP personnel has been examined in the literature over the past several decades. As the areas for which IP is responsible and the demands on IP time change, prior data regarding the number of IPs per hospital bed or patient care areas may no longer apply.

5 The scope of IP responsibilities may differ between facilities based on size, teaching status, provision of specialty care, and patient population, and thus estimates for the number of personnel generated by these studies may not be a perfect fit for every facility. The Study on the Efficacy of Nosocomial Infection (SENIC) project, published in 1980, was the first to recommend a certain number of IP personnel per hospital bed.

6 In 2002, O’Boyle recommended a ratio of 0.8-1.0 IP per 100 beds based on their survey study.

7 This recommendation was based on changes in patient characteristics along with changes in the tasks that IPs perform. Stone et al.

8 reported a median ratio of 1 IP to 167 hospital beds based on a national survey of current staff levels in an article published in 2009. They note that larger hospitals had a lower ratio than smaller hospitals. In 2018, Bartles et al. reported that an ideal level for their large organization would be 1 IP to 69 beds; however this also includes IP activities in various long-term care and outpatient settings.

5A healthcare epidemiologist (HE) is a medical professional with skills and competencies which are outlined by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) in a White Paper.

9 In most instances, a HE is a physician with specialty training in infectious diseases; however, they may instead be a member of another closely related discipline such as a microbiologist, public health professional, internist, or hospitalist, among others. HEs perform multiple roles and ideally have expertise in seven distinct areas outlined in

Table 10-1. The range and scope of these

content areas requires ongoing engagement with healthcare epidemiology colleagues and the medical literature along with professional societies to develop and maintain the requisite skill set.

The IP program’s activities may also be supported by data analysts, laboratory technologists, quality improvement specialists, and administrative staff. These roles are becoming ever more important as reporting requirements continue to increase over time. The ability to accurately capture, interpret, and utilize data is an essential skill in order to effectively drive IP activities, develop policies, detect and respond to outbreaks, participate in national and state level reporting of data, and communicate with organizational leaders.