Detection and verification of an outbreak epidemic of human-swine streptococcal bacteria for the first time in China

Outline

In the summer of 1998, some cases with similar clinical symptoms occurred simultaneously in 4 adjacent counties (cities) in the mid-region of Jiangsu province in China. These cases had complex clinical features that were life-threatening, affecting multiple organs, causing damage to and failure of these organs and eventually deaths of the affected. Some clinical features of these cases were similar to that of the streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) reported in foreign countries [1,2]. After receiving the report of the disease, the Health Department of Jiangsu Province organized a rapid epidemiological investigation and pathogen detection and subsequently confirmed that such an infectious disease was originated from sick (dead) pigs. After the implementation of comprehensive measures including prohibition of sacrificing sick (dead) pigs, the epidemic was quickly brought under control.

The control of this epidemic was a successful case in the investigation and handling of the “unknown” diseases in Jiangsu Province; and it was also a typical case in which the cause was epidemiologically clarified through the field investigation and well-targeted control measures were taken timely in the absence of a clear pathogen to achieve an effective control of an epidemic of an “unknown” disease.

1. Identification and Report of the Epidemic

In the evening of June 27, 1998, the office of epidemic prevention station of Nantong City of Jiansu Province was informed that in the city’s hospital of infectious diseases there was a suspected case of anthrax who was in critical conditions. The office of epidemic prevention station immediately dispatched professional health workers to the hospital where the case was to collect information of the disease and reported to the office of epidemic prevention station and the Department of Health of Jiangsu province.

2. Organization and Preparation

Immediately after receiving the report, the Office of the Department of Health of Jiangsu Province quickly mobilized and organized professionals in epidemiology, laboratory and food and health workers who formed a team that rushed to assist in the investigation and handling in the epidemic field.

Before conducting investigations, the team performed a comprehensive overview of the event and carefully evaluated the investigation methods to be implemented, expected results, initial steps to be taken and expect outcomes. Meanwhile, before

going to the epidemic field, the field investigation team were fully prepared with necessary information and goods, including the questionnaire, survey equipment, on-site prevention and control equipment, sampling equipment, reagents, computers, cameras, personal protective equipment and appropriate transportation vehicles.

going to the epidemic field, the field investigation team were fully prepared with necessary information and goods, including the questionnaire, survey equipment, on-site prevention and control equipment, sampling equipment, reagents, computers, cameras, personal protective equipment and appropriate transportation vehicles.

3. Verification of Diagnosis

After arriving at the field, the working group launched a rapid epidemiological investigation. Preliminary findings revealed that prior to this new case there had been 8 similar cases which had relapsed without effective treatments in the same and surrounding areas. According to the local residents, recently there were a large number of sick pigs that were later dead in the area. The working group immediately reviewed each of 8 cases with summarized descriptive analyses on their epidemiological features.

1) Case investigation the working group interviewed each case with a standardized questionnaire which included information about general physical conditions, signs and symptoms, laboratory testing results, treatment and prognosis, recent dietary intake, drinking water conditions, contact history with sick or dead livestock, surroundings of the patient family, any similar cases occurred in surroundings of the patient family, and any sick and dead animals in surroundings of the patient family.

2) Descriptive epidemiology all cases were male, mostly young and middle-aged. It appeared that the patients did not have any direct contact with each other, and no suspicious circumstances were discovered in the history of drinking water, diets, and domestic traveling. But they all had a contact history with sick or dead pigs, and most of them had obvious damaged skin in the hands and arms.

3) Main clinical features most cases had a number of symptoms in the initial phase, including high fever, general malaise, headache and dizziness. The disease course started with a sudden onset with an abrupt high fever accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms, followed by ecchymosis and purpura in the distal parts of extremities in the early stage and progression to shock. The patient experienced a rapid deterioration into the failure of multiple organs, such as respiratory distress syndrome, heart failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation and acute renal failure, with poor prognosis and a high mortality.

4) Primary diagnosis the working group performed all relevant laboratory tests on samples of blood, urine, stool samples and throat swabs and ruled out the following known communicable diseases: anthrax, epidemic hemorrhagic fever, typhoid, malaria and leptospirosis. According to the patients’ symptoms, signs and laboratory data combined with descriptive epidemiology information as well as consultation with all experts, the disease was initially diagnosed as “the septic toxic shock syndrome.”

4. Confirmation of Epidemic

Through preliminary investigation, the investigators gradually had a comprehensive understanding of the epidemic. Clinical manifestations of the cases were complex and dangerous, and most suffered damage to multiple organs, similar to that of the streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) reported abroad in

1990s; therefore this was further confirmed as an event of aggregative epidemic of “the septic toxic shock syndrome”.

1990s; therefore this was further confirmed as an event of aggregative epidemic of “the septic toxic shock syndrome”.

Through the field epidemiological investigation, it was also found that there were some cases that had the signs and symptom similar to that of meningitis, such as headache, high fever, and positive meningeal irritation signs. The cases of this type had less severe clinical manifestations with a better prognosis and a lower mortality rate, but meningitis was excluded from the initial diagnosis. The cases of meningitis type had similar epidemiological characteristics to that of the cases with “the septic toxic shock syndrome”, and both had a contact history with sick (dead) pigs and the obviously damaged skin.

5. Establishment of a Hypothesis for the Cause of the Disease

According to epidemiological findings from the preliminary investigation, using the cause inference rules such as the methods of agreement, concomitant variation and exclusion, it was hypothesized that the epidemic cause was a “group infection caused by bacteria derived from sick (dead) pigs that produced relatively poisonous toxin”. The infectious route was through a direct contact, that is, those people who had a close contact with sick (dead) pigs were more likely to be the high-risk population, and in particular, those with wounds or damaged skin were more susceptible. Given that “poisoning infection shock syndrome” and cases of meningitis type had similar epidemiological characteristics, it was suggested that cases with these diseases may have a shared and common source of infection or pathogens.

6. Proposed Control Measures

Based on the preliminary hypothesis, a comprehensive control measure suggested was to prohibit the sacrificing sick (dead) pigs that would reduce a direct contact.

6.1 Health education

through the publicity and education, personnel responsible for pig slaughtering and processing were made aware of the hazards in contacts with sick or dead pigs, and required to exercise their own precaution; health workers also provided personnel training of the ability to recognize sick pigs and pork from sick pigs, and the traning was extended to those working in pig-raising households and butchers; pig-raising households were asked to actively report ant epidemic of sick pigs, to bury sick or dead pigs locally and not to throw dead pigs into waters such as the river, the valley, and the pool; local residents were advised not to buy or eat pork of the sick and dead pigs.

6.2 Preventive medication

for those regions with streptococcus swine disease epidemic, pigs in the same pigsty with a close contact with sick pigs were administered with preventive medication (antibiotics). For those regions without swine disease epidemic, it was not advised to implement preventive medication to avoid the production of resistant strains.

6.3 Disease surveillance and quarantine of live pigs

the epidemic reporting system of

live pigs was established and improved. Microscopic examination and pathogen isolation and identification were regularly conducted on any lesions, septic foci, blood, lymph nodes and other tissues sampled from sick or dead pigs. Centralized slaughtering system of pigs was implemented with unified quarantine. It was strictly prohibited on slaughtering sick or dead pigs, meanwhile quarantine and management on marketed pork was strengthened with a ban on selling pork from sick or dead pigs.

live pigs was established and improved. Microscopic examination and pathogen isolation and identification were regularly conducted on any lesions, septic foci, blood, lymph nodes and other tissues sampled from sick or dead pigs. Centralized slaughtering system of pigs was implemented with unified quarantine. It was strictly prohibited on slaughtering sick or dead pigs, meanwhile quarantine and management on marketed pork was strengthened with a ban on selling pork from sick or dead pigs.

6.4 Disinfection of epidemic spots and epidemic areas

it was recommended to use disinfection fluid containing 1% available chlorine or 0.5% peracetic acid that should be sprayed or wiped on the roads leading to the patients’ homes and pigsty of sick pigs, and the ground, walls, doors and windows, door handles in the patients’ homes.

It was also recommended to blend disinfectant with excretion and vomited substances of the patients and to soak its container with disinfectant. The corpse of dead patients should be disinfected before cremation. Effective disinfectants were also sprayed on the corpse surface of sick or dead pigs and then bury them as deep as two meters after stuffing their noses, mouths, ear cavities and other openings with the 0.2% peracetic acid cotton balls, and place a layer of bleaching powder in the bottom of the hole, keeping a distance of more than 50 meters far away from the source of drinking water.

6.5 Implementation of comprehensive control measures

the working group initiated the implementation of control measures under the leadership of local governments:

1) To strengthen health surveillance, and maintain active monitoring and reporting on pig epidemic and human epidemic.

2) To comprehensively clean up external environment, and reinforce the protection of drinking water sources.

3) To focus on strengthening management of personnel responsible for slaughtering and implement comprehensive control measures mainly on strict prohibition on slaughtering sick (dead) pigs and selling the pork.

4) To dispatch the inspectors at all levels of government and responsibilities to petrol individual villages and to take active prevention and control measures under the leadership of the departments of public security, industry and commerce.

7. Establishment of Diagnosis Criteria

At the beginning of the epidemic, because of lack of etiological evidence, diagnosis criteria were mainly formulated based on epidemiological and clinical features. But with the emerging of advanced laboratory testing, the clues of etiological evidence gradually became clear, and other infectious diseases, such as anthrax, epidemic hemorrhagic fever, typhoid, malaria and leptospirosis, were successfully excluded.

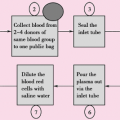

The patients’ samples, such as specimens of blood, and cerebrospinal fluid and internal organs of sick and dead pigs (heart, liver, spleen, kidney, lymph nodes), were collected through aseptic operation, and then directly inoculated on the culture media such as blood agar or reproducible medium. Colonies were identified

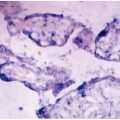

morphologically by the Gram staining method, and the simultaneously trace biochemical test and API biochemical test were also conducted. Highly suspicious bacteria isolated from the patients were identified as streptococcus bacteria, and streptococcus bacteria and Pasteur streptococcus bacilli were isolated from pig specimens. (See “Laboratory Tests”)

morphologically by the Gram staining method, and the simultaneously trace biochemical test and API biochemical test were also conducted. Highly suspicious bacteria isolated from the patients were identified as streptococcus bacteria, and streptococcus bacteria and Pasteur streptococcus bacilli were isolated from pig specimens. (See “Laboratory Tests”)

By referring to diagnostic criteria for the streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) formulated by Center for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States in 1993 and combined with characteristics of this disease, the diagnostic criteria were formulated as follows [2]:

7.1 Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS)

1) Detection of Streptococcus bacteria: streptococcus bacteria can be isolated from sterile sites such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid and other places.

2) Clinical features: a decrease in blood pressure, and two or more following multiple organ dysfunctions accompanied with adult systolic blood pressure at 12 kPa (90 mm Hg): a) renal insufficiency; b) blood coagulation disorders; c) liver dysfunction; d) acute respiratory distress syndrome; e) systemic ecchymosis and purpura; and f) soft tissue necrosis, fasciitis, myositis, and gangrene.

3) Contact history with sick or dead pigs: had close contacts with sick or dead pigs a few days before the onset of the disease, such as slaughtering, marketing, and processing of the sick or dead pigs.

The diagnosis can be confirmed if complying with items 1) and 2) simultaneously, or item 2) and 3) simultaneously, excluded from other known infectious diseases.

7.2 Streptococcal meningitis syndrome

1) Detection of streptococcus bacteria: the same as above.

2) Clinical features: a) meningeal irritation symptoms; b) CSF purulent change.

3) Contact history with sick or dead pigs: the same as above.

The diagnosis can be confirmed if complying with items 1) and 2) simultaneously, or item 2) and 3) simultaneously, excluded from other known infectious diseases.

8. Descriptive Epidemiology

In this epidemic, there were a totaled 25 incident cases, of which 16 cases met the diagnostic criteria of STSS and 13 were dead with a mortality rate of 81.25%; 9 cases met the diagnostic criteria of streptococcal meningitis syndrome and 1 was dead [2,3].

Case distribution was relatively concentrated, mostly in 4 adjacent counties: Rugao, Haian, Taixing, Tungzhou. All patients had a direct contact history with sick, dead pigs or unknown sources of pork two days before the onset of illness, of which 19 cases had a history of slaughtering sick or dead pigs (76%); 3 cases had a history of pork sales (12%), but it was unable to ascertain the nature of pork of various sources; and another 3 cases had a history of washing, cutting pork or dead pig skin peeling (12%). There were 7 cases out of the 25 cases whose hand skin had obvious lesions (28%), and there were sick or dead pigs occurred near the surrounding of the homes where 20 cases lived. No deaths of other animals (such as mice, chickens, sheep, cattle, dogs, etc.) were observed the homes of any cases who

also did not have any exposure to obvious unclean source of drinking water and food.

also did not have any exposure to obvious unclean source of drinking water and food.

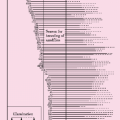

8.1 Time Distribution

through retrospective investigation by reviewing the cases occurring before July 27, the first case with STSS occurred on July 20, and the last case occurred on August 8. During this period, it was a hot season, hot and humid, and rainy in this region.

The distribution of the onset dates of 16 cases with STSS: 5 case between July 20 and 25, 5 case between July 26 to 31, 3 case between August 1 and 5, 3 case between August 6 and 8; The distribution of the onset date of 9 cases with streptococcus meningitis syndrome: 1 case onJuly 21, 3 cases between July 30 and August, 2 cases on August 2, 1 case on August 3, and 1 case on August 5.

8.2 Location distribution

the cases were located in the neighboring 4 counties (cities), 23 townships and 25 villages, which showed in a continuous or discontinuous patterns between villages, but the characteristics of case distribution were relatively concentrated and highly spattered. A total of 7 cases with STSS and 9 cases with streptococcus meningitis syndrome occurred in counties with more prevalent cases, and there were no obvious contact history between the cases. However, the epidemic of sick pigs also occurred in 4 adjacent counties (cities), 23 townships and 25 villages. The geographical distribution of human epidemic was identical with that of sick pigs.

8.3 Population distribution

there were 16 cases with STSS and 9 cases with streptococcus meningitis syndrome who were male; Minimal age was 29 years and maximal age was 75 years; 3 cases in “30˜” age group, 8 cases in “40 ˜” age group, 7 cases in “50˜” age group, 4 cases in “60˜” age group, and 2 cases in“70˜” age group; 25 patients were living in the rural areas; 5 patients were professional butchers, three patients were pork sellers; and 17 patients only had one contact before the onset of sick or dead pigs. However, the distribution of cases did not show a family aggregation. There were no contacts between patients and no infectious cases were found among those who had a close contact with a patient infected with the disease.

8.4 The relationship between human-to-human epidemic and porcine-to-porcine epidemic

before local human-to-human cases arisen, there were a large number of dead pigs more than 10 times of those in the same period last year. The human-to-human epidemic occurred later than the porcine-to-porcine epidemic, and the termination of human-to-human epidemic was earlier than that of porcine-to-porcine epidemic. In the county with the most serious epidemic of sick pigs, there were a total of 14,246 sick or dead pigs between July and August, accounting for 1.5% of local pig number. This county had the most cases with the disease as many as 16 cases in the cities.

9. Clinical Characteristics

9.1 Clinical characteristics of sick pigs

1) Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS): the disease started with acute high fever (100%) with maximal temperature at 42°C; accompanied by headache (56.25%) and diarrhea and other gastrointestinal symptoms (68.75%); Subsequently ecchymosis and purpura occured beneath the skin (81.25%), mainly distributed in the limbs, head and face, without bumps on the skin nor ulcer; multiple organ damage rapidly emerged, such as oliguria, renal failure (81.25%) and liver dysfunctions, and quickly developed into shock (100%) with a high mortality rate (81.25%). The disease latent period was within the 2 days with the the shortest of 3 hours from exposure to sick or dead pigs, and 10 of 16 patients had the disease onset (62.50%) within one day.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree