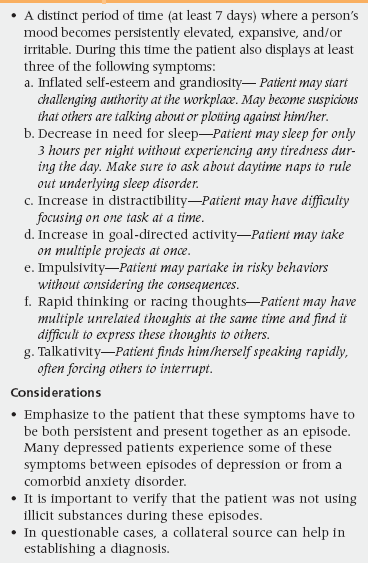

18 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Understand the impact of depression on a patient’s general medical condition and quality of life. • Identify risk factors for depression and suicide, and interventions for each. • Describe the differences in presentation between late-life depression and early-onset depression. • Assess for various types of depression including major depression, subsyndromal or minor depression, dysthymia, and depression secondary to substance use or a general medical condition • List common screening tools and lab tests to be performed when considering a diagnosis of depression. • Discuss treatment options for depression including medications, psychotherapy, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and rapid transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). • Identify cases that need referral to a psychiatrist or emergent psychiatric intervention. People age 65 and older currently make up 13% of the total U.S. population; that percentage is expected to rise to about 20% by the year 2030.1 There are approximately 39 million elderly individuals in the United States and about 7 million of them are affected by depression.2 Depression comprises the largest category of psychiatric disorder in the elderly and is currently the fourth leading cause of disability as estimated by disability-adjusted life years.3 By 2020, depression will be second only to heart disease as a cause of disability in the global population.4 In contrast, there will be approximately 2,640 geriatric psychiatrists in the United States by the year 2030, or 1 per 5,682 older adults with a psychiatric disorder.5 It is therefore imperative that primary care providers are able to detect and treat depression in the elderly. There is a common misconception that depression occurring in late life is a normal part of the aging process, or a normal reaction to stressors such as retirement, the loss of loved ones, medical ailments, and loss of independence. In fact, an enduring finding in epidemiologic studies is that only a small number of elderly people living in the community admit being depressed.6 A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report in 2006 estimated that approximately 5% of community-dwelling adults age 65 and older reported being currently depressed.7 Rates of depression are higher in older adults who require more care or are in institutional settings. Fourteen percent of patients receiving in-home care8 and approximately 20% of nursing home residents9 meet criteria for depression. However, only a small percentage of older patients with depression receive proper treatment for their symptoms; those most likely to receive inadequate or no treatment for their depression are male, African American, Latino, and those with a preference for counseling over antidepressant treatment.10 Depression in the elderly is often associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Schulz et al. followed a group of more than 5000 individuals over 65 years and found that those with higher baseline depressive symptoms were one and half times more likely to die.11 The mortality rate coincided with the level of depression even when controlling for other factors. Older patients who report depressive symptoms are also more likely to report a lower quality of life, higher level of chronic pain, and increased disability.12 Medically ill patients with depression have increased total health care costs. One study found that depressed patients with heart failure and diabetes had almost double the health care costs of nondepressed patients ($20,046 vs. $11,956).13 In addition, it is estimated that friends or family members who are serving as primary caretakers of these patients provide approximately $375 billion of unpaid work annually.14 Late-life depression shares much in common with depression occurring earlier in life but has unique, distinguishing characteristics in presentation, etiology, and risk factors. In younger adults, the stress-diathesis model is one of the more popular explanations for why people develop depression. This theory suggests that both genetic vulnerability and psychosocial factors play important roles. In contrast, whereas psychosocial factors play a part in the development of late-life depression, there is less consistent evidence for genetic predisposition, with studies showing little correlation between family history and late-onset depression.15 However, other biological factors are important. For example, compromises in brain neurocircuitry, particularly in frontolimbic pathways, have a strong association with many depressive disorders in late life. This may explain the high incidence of depression in patients with neurologic conditions affecting these pathways such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD).16 Although the biological processes of late-life depression may separate it from early-onset depression, the aforementioned stress diathesis model is still useful in emphasizing the importance of psychosocial risk factors15 (Table 18-1). These risk factors in turn can be modified by other factors including a patient’s coping skills and the presence of ongoing stress outside of the context of the psychosocial risk factor. It should also be recognized that a majority of individuals with a given risk factor will not meet depressive criteria. Rather, the risk factors should be considered when suspecting depression and in the formulation of treatment. TABLE 18-1 Chronic medical illness Loss of a loved one Relocation Disability Diagnosing depression in the elderly at times can be a challenge. Although the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) are the basic construct for depression in the older population, there are distinctions in how depression may present. Older depressed individuals have a higher tendency to have somatic complaints (primarily gastrointestinal), hypochondriasis, and agitation but are less likely to have low self-esteem or guilt compared to younger persons.17 In addition, older depressed patients tend to have a higher rate of psychotic and severe (melancholic) depression with more weight loss and decreased appetite.18 Occasionally, depression in the elderly may be masked in that the patient denies any emotional disturbance but instead reports a multitude of physical symptoms. Family members may report that the patient has lost interest in activities or has had a change in affect. In such circumstances, there is an obvious barrier to recognition of the depressive illness, though when investigated, somatic complaints are out of proportion to the medical illness. There may also be a chronologic correlation between new or worsening physical complaints and the onset of an identifiable stressor that alerts the provider to consider depression as a diagnosis. Two other subtypes of depression of importance are dysthymic disorder and minor or subsyndromal depression. Dysthymic disorder is a more chronic form of affective disorder (duration longer than 2 years) characterized by two or more of the following symptoms: poor appetite or overeating, sleep disturbance, low energy or fatigue, difficulty with concentration, indecisiveness, feelings of hopelessness, and low self-esteem (DSM-IV-TR). Unlike MDD, dysthymic disorder is associated with a younger age of onset19 and presenting symptoms are similar to younger cohorts. Although dysthymic disorder is unlikely to occur in late life, it may persist from midlife into late life.20 Subsyndromal depression is also known as minor depression in the DSM-IV-TR and is diagnosed when the number of depressive symptoms is below the number needed to establish a diagnosis of MDD (i.e., between two and four symptoms). Subsyndromal depression is often present with comorbid chronic medical illness leading to functional decline. One study identified vision loss as the illness most readily associated with this form of depression.21 Subsyndromal depression may lead to the same level of disability as MDD and is associated with increased mortality.22 Several epidemiologic studies have shown subsyndromal depression to have a 2 to 3 times higher prevalence than MDD in the elderly, with a point prevalence of approximately 9.8% in community-dwelling seniors and as high as 35% of primary care geriatric patients.23 Diagnosing depression can be particularly difficult in the setting of bereavement where the overlap of symptoms typical of normal grieving and major depression can be extensive. However, multiple studies have shown that the two can be differentiated and that persons who develop late-life depression after loss of a loved one have distinctive outcomes. What differentiates any normative process from psychopathology is its effect on functioning. Typically, the bereaved individual does not become functionally impaired or is minimally impaired. Grief and bereavement also do not typically involve active suicidal thinking; rather, the bereaved may have passive thoughts about “joining” their loved one. Although it is not uncommon for grieving individuals to feel that they have seen their loved one in a crowd or hear the deceased calling their name, florid psychosis in the form of prolonged auditory or visual hallucinations and delusions should raise suspicion of another underlying psychiatric disorder. Cultural background plays a major role in the length of time an individual will grieve, but it is generally expected that a person will begin recovery within 1 year after his or her loss. An evolving concept in the study of grief is complicated grief, a protracted, severe form of grieving in which a person experiences strong feelings of anger or bitterness about the loved one’s death, feelings of emptiness, a persistent longing to be with the loved one, recurring intrusive thoughts about the loss, and reclusiveness from family and friends.24 To be diagnosed as complicated grief, these symptoms must persist for 6 months or more. Complicated grief differs from clinical depression in that the former’s presenting symptoms are more focused on the loss. Although both diagnoses carry some level of dysfunction, the distinction is important because persons experiencing complicated grief have inconsistent responses to antidepressants and psychotherapeutic treatments useful for MDD.25 Shear and colleagues proposed complicated grief therapy (CGT), as specific therapy in this condition.26 CGT combines features of cognitive behavioral and interpersonal therapy in which patients revisit the loss of their loved one under guidance of a therapist to bring resolution. The therapist also aids the individual to engage in situations and activities that were once avoided because of the loss. Preliminary studies show that CGT has better results than standard interpersonal therapy for treatment of complicated grief.26 A particular challenge occurs when depression overlaps with cognitive impairment. In one scenario, depression may arise with co-occurring cognitive dysfunction. This presentation has a variety of names including depressive pseudodementia and dementia syndrome of depression. The initial view was that patients developed cognitive deficits as one element of a severe neurovegetative state related to a depressive disorder and that, as the depression resolved, so did cognitive impairments. What seems clear now is that this clinical presentation includes a number of conditions that can be distinguished largely by their outcomes. The classic presentation referred to above does occur and is important to identify because these patients have one of the truly reversible causes of dementia. It is now known that even those who have an excellent response to treatment and clear cognitively have an increased risk of developing dementia in ensuing years.27 Another scenario is for patients to develop a depressive disorder and, over time, gradually become cognitively impaired and eventually develop dementia, suggesting that late-onset depression can serve as a prodrome or a forme fruste of a dementing disorder. An interesting study further explored the relationship between depression and dementia by examining if depression that first occurred in midlife carried a different prognosis than that developed for the first time in the senium. The risk of developing dementia was increased by 20% when midlife depressive symptoms were present, by 70% when only late-life symptoms were present, and by 80% when depressive symptoms were present at both times.28 When these risks were evaluated by type of dementia, subjects with late-life depression had only a twofold increase in risk of AD. However, patients with depressive symptoms in both midlife and late life had a more than threefold increase in vascular dementia risk. The authors concluded that depression occurring either in midlife or in late life is associated with a higher risk of developing dementia and that the pattern is important. New depression in late life is more likely to be part of an AD prodrome, and recurrent depression is more strongly associated with vascular dementia.28 Another common pattern is the group of patients with minimal to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or early AD who, after diagnosis, become depressed. At times this reflects the overlap in symptoms that dementia and depression share: decreased energy, problems with concentration, psychomotor changes, and loss of interest.29 Although families often feel that this constellation represents depression, apathy is frequently one of the most common behavioral and psychological syndromes that affects those with early AD. Current theory suggests late-life depression can be either a prodrome or a risk factor for AD. Depression commonly occurs in AD, and late-life depression itself can include cognitive deficits. There is evidence that amyloid deposition begins decades before clinical diagnosis of AD is made. A study exploring the deposition of amyloid and tau protein using positron emission tomography (PET) scans found a higher binding rate in patients with a diagnosis of MDD.30 Moreover, these protein depositions were found in the posterior cingulate and lateral temporal areas of the brain known to be involved in AD.30 Additionally, a study by Gerritsen et al. exploring depression and its correlation with changes in hippocampal and entorhinal volumes noted that patients experiencing a first episode of depression in late life exhibited volume loss in entorhinal rather than hippocampal structures, the latter being seen in early-onset depression.31 Although this preliminary evidence for an underlying biological correlation between AD and depression is intriguing, further studies are needed before a definite connection can be established. This relationship has been extensively explored in the setting of stroke. Approximately 20% of stroke victims develop MDD and another 20% develop minor depression.32 Conversely, depression itself is a risk factor for stroke.33 Those that develop poststroke depression tend to have a greater decline in activities of daily living (ADLs),34 less recovery of functioning,35 greater impairment of cognition,36 and increased mortality37 compared to nondepressed stroke patients. Adequate treatment of poststroke depression improves outcomes in both ADLs and cognitive impairment.38,39 Additionally, preventative treatment after stroke with antidepressants may reduce incidence of significant morbidity and mortality. A multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) compared escitalopram to placebo or problem-solving therapy (PST) for prevention of depression 1 year after acute stroke. Patients receiving placebo were 5 times more likely to develop poststroke depression compared to escitalopram and those receiving PST were 2 times more likely.40 A follow-up study showed patients given escitalopram were more likely to develop depression 6 months after discontinuation of treatment whereas patients receiving PST or placebo were not.41 Vascular depression has been proposed as a distinct form of depression related to cerebrovascular disease but not to a discrete stroke. These patients are clinically identified based on symptoms that include substantial psychomotor retardation, apathy, and pronounced disability. They have vascular lesions on neuroimaging, a poor response to treatment, unstable remissions, and a higher risk of developing dementia.42 Vascular depression is felt to result from small vascular insults to cerebral structures leading to dysfunction in brain neurocircuitry, primarily in the frontolimbic and frontostriatal systems. Also, white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been correlated with a decreased response to antidepressants, although this has been inconsistent and requires further exploration.43 Likewise, preexisting vascular burden may be a determining factor in whether executive dysfunction improves in older depressives in response to treatment.44,45 Additionally, inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein [CRP]), fasting glucose, and the metabolic syndrome, which all have effects on vascular functioning, have been independently associated with the onset of depressive symptoms in the elderly.46 Other chronic medical illnesses with high rates of depression are arthritis, heart disease, and cancer; in these, the level of functional disability is strongly associated with depression.47 The most robust data available is in patients with heart disease. Cardiac conditions such as heart failure and acute myocardial infarction (MI) are strongly correlated with depression; approximately 20% to 40% of individuals with these conditions have MDD.48 Patients who develop depression shortly after an MI have increased mortality.49 In fact, patients with ischemic heart disease taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have a reduced rate of MI.50 Although heart disease and the other aforementioned conditions correlate with depression, it is not clear if the mental or the physical ailment is the causative factor. Delirium is a condition that is misdiagnosed as depression up to 40% of the time.51 Although hyperactive delirium may present with agitation and bizarre behavior, hypoactive delirium displays symptoms similar to depression including apathy, indecisiveness, and psychomotor retardation, accompanied by memory and functional impairment. The clinical setting for these misdiagnoses is most often the inpatient setting where a patient suddenly begins to refuse interventions or participation in care and the assumption is that the patient has “given up.” Delirium should be suspected if both mood and cognitive symptoms occur with rapid onset (hours to days) and have a fluctuating course. Cognitive screening tests can be serially administered to document changes in cognition. The primary treatment for delirium is to find the underlying cause. Antidepressants have no role in this setting. According to a 2012 report from the Institute of Medicine approximately 5.6 to 8 million older adults had one or more mental health or substance use conditions. This number is expected to increase 80% by the year 2030.52 Substance abuse, although not as common among the elderly, is an important problem in late life that can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. As a result, mood disorders related to substance use should always be included in the differential diagnosis. Alcohol is overwhelmingly the most common misused substance in late life, although with baby boomers aging, marijuana use may become common. According to the DSM-IV-TR criteria, when considering substance-induced depression secondary to drug abuse or dependence, it is important to have chronologic evidence of mood symptoms “developing during, or within a month of, substance intoxication or withdrawal.” In some cases, a patient may be using a substance to “self-medicate” the underlying mood disorder. It is important to elicit a history to establish if the mood symptoms were present during extended periods of sobriety. In addition to substance abuse, iatrogenic depression may also occur from commonly prescribed medications such as benzodiazepines, opiates, and steroids. Although beta-blockers have received much attention for possibly inducing depression, this association is inconsistent.53 Regardless of type of medication, if depression begins within 1 month of starting a medication, especially if a patient has no history of prior depression, it can be presumed that it may be medication induced. If depression is possibly secondary to a newly prescribed drug, the medication should be discontinued or substituted and the patient monitored for mood improvement. It is important to screen for bipolar disorders by asking about a history of mania (Table 18-2). Presentation of bipolar depression is virtually identical to unipolar depression and only properly inquiring about a previous manic episode will differentiate the two. It is also important to avoid antidepressant treatment in bipolar patients, where mood stabilizers such as lithium and lamotrigine would be first-line treatment. Outside of the presenting complaint, additional inquiries regarding the patient’s substance use—past and present—are essential because substances play a role in mood regulation, have long-term effects on the brain, and can negate the effects of psychotropic treatment. Medications should also be reviewed, including correlation between onset of symptoms and the start or change in a medication. Depression rating scales can be useful in identifying depression in an older patient. A commonly used scale is the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS),54

Depression

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Diagnosis of late life depression

Differential diagnosis

Normal grief and bereavement

Complicated grief

Depression and cognitive impairment

Depression secondary to a general medical condition

Substance-induced depression

Assessment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine