© Springer International Publishing AG 2017

Olufunso Adebola Adedeji (ed.)Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa10.1007/978-3-319-52554-9_1111. Delivering Safe and Affordable Cancer Surgical Care

(1)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals, Basildon, Essex, UK

(2)

Faculty of Applied Sciences, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, UK

(3)

Faculty of Law, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

(4)

Department of Colorectal Surgery, The Whittingthon Hospital, London, UK

(5)

University College London, London, UK

Abstract

Cancer is a growing health burden in Africa; the annual number of new cases will grow to more than 1 million. Together with the immense loss in human life, there is a considerable economic setback. The scale of the problem is enormous and seemingly insurmountable. Despite successful surgical treatment, there is a high disability and mortality rate in sub-Saharan Africa due to the lack of affordable and available surgery. There are many challenges; lack of medical services and personnel, lack of access, and socio-cultural beliefs. The disparity in cancer risks combined with poor access to epidemiological data, research, treatment, and cancer control and prevention result in significantly poorer survival rates in sub-Saharan Africa. The aim should be co-operative development of a range of facilities, education and ease of access. Surgery remains at the centre of cancer management. The focus of African governments and the international community should be recognition of surgical care as an essential component of global cancer control.

Keywords

CancerSurgerySub-Saharan Africa11.1 Introduction

Over 80% of the 15 million people diagnosed with cancer worldwide in 2015 was estimated needed surgery, but less than one-quarter of them would have had access to proper, safe, affordable surgical care (Sullivan et al. 2015). In poorly resourced countries, the delivery of safe, affordable, equitable surgical cancer care to all those who need it through multidisciplinary teams of Surgeons and Anaesthetists remains an ideal (Lingwood et al. 2008). The Commission examining the state of global surgery found access worst in low-income countries, where as many as 95% of people with cancer do not receive basic cancer surgery (Lingwood et al. 2008; Sullivan et al. 2015). It is expected that by 2020, there are likely to be 16 million new cases of cancer every year, 70% of which will be in developing countries. It is estimated that 100,000 children die unnecessarily from cancer in the developing world each year (Yaris et al. 2004). In Africa, on average 5% of childhood cancers are cured, compared to an 80% cure rate in the developed world (Lingwood et al. 2008).

Although infectious diseases continue to afflict Africa, the proportion of the overall disease burden in sub-Saharan Africa attributable to cancer is rising, and the region is predicted to have a greater than 85% increase in cancer burden by 2030 (Sandro et al. 2013). Many of these cancers are preventable, or treatable when detected early enough. At the same time, development and delivery of safe and affordable cancer care in the region has been very rudimentary, if at all available.

Two-thirds of the world population have no access to safe surgery which equates to about five billion people. One-third of all deaths and disabilities in 2010 were treatable with safe surgery. In Africa, this is exacerbated by its growing population with more people now reaching middle age, and the prevalence of cancer increasing with the increase in life expectancy. Cancer causes more morbidity and mortality in Africa compared to other parts of the world. Establishing effective, affordable and workable cancer control plans in African countries is one step in the right direction toward limiting this epidemic. There is considerable evidence that good surgical service, combined with anaesthesia is essential integral component of a functional cancer care.

11.2 Scale of the Problem

The management of cancer is expensive and in the face of scarce resources and other competing priorities, cancer care in sub-Saharan Africa has been poor. Most Africans have no access to cancer screening, early diagnosis, treatment or palliative care as there are few cancer care services. As a result of poor investment in cancer services, access to safe and affordable cancer surgical services is dismal. New estimates suggest that less than one in twenty (5%) patients in low-income countries and only roughly one in five (22%) patients in middle-income countries can access even the most basic cancer surgery (Meara et al. 2013). Majority of cancer sufferers have probably not been diagnosed, let alone treated. The other problem is high fatality rates as a result of late presentations and low operative volumes. It is likely that poorly resourced centres will not be able to carry out highly skilled, cutting edge surgery often required to achieve aggressive, adequate oncological clearance of the disease bulk. Surgical approach has significant curative potential when combined with appropriately selected adjuvant systemic treatment and radiotherapy (Lingwood et al. 2008).

Unfortunately, 93% of people in sub-Saharan Africa do not have access to adequate surgical care. Key challenges are lack of essential medical facilities, lack of access to facilities due to travel distances, lack of surgeons and anaesthetists to provide safe service; and heavy costs of medical services (Dare et al. 2015). To compound this, cancer care in Africa is affected by myths about the disease, leading to late presentation and the inevitable painful and distressing death. Another major obstacle to the delivery of care, even to the small proportion of patients who present with potentially curable cancer, is the lack of skilled health professionals such as pathologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, nurses, pharmacists and other health-care workers needed for cancer care.

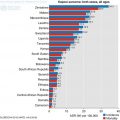

Literature review of surgical services in sub-Saharan Africa in 2010 (excluding South Africa) revealed that the number of surgeons was less than two surgeons per 100,000 inhabitants (Lavy et al. 2011). In England, there were greater than 35 surgeons per 100,000 people. The consequence was that, in many district hospitals, surgery and anaesthesia were (and still are) carried out by non-physician personnel, who underwent some form of training to perform those tasks. In referral hospitals, most of the oncologic surgery was performed by general surgeons (Gyorki et al. 2012).

The combination of late presentation and the dearth of cancer services create a problem that requires an urgent intervention. It is even compounded by the fact that policy makers at all levels still have little awareness of the central importance of surgery to cancer control. Recent studies of capacity building for cancer systems in Africa barely acknowledged the importance of surgery, focusing mainly on chemotherapy instead (Sullivan et al. 2011).

11.3 Financial Constraints and Infrastructure

In addition to the lack of personnel, there is a dearth of cancer management infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa. Existing structures are poorly equipped and maintained. There is also a gap in the provision of the full range of services required for optimum cancer treatment. With many competing health priorities and significant financial constraints, surgical services in these settings are given low priority within national health plans and are allocated few resources from domestic accounts or international development assistance programs.

In an effort to foster collaboration and coordination between the various institutions working for cancer control on the continent, the African Organization for Research and Training in Cancer launched the African Cancer Network Project in 2012. It published a list of cancer treatment, research, teaching, advocating, fund-raising, and administrative entities in Africa. The list contained 102 cancer treatment institutions, including general oncology centres, gynaecologic oncology or other single-organ malignancy units, and paediatric oncology and palliative care establishments. Of these institutions, 38 are located in South Africa (Thomas 2004). The list indicates that there is a massive undersupply of cancer care services on the continent. Additional obstacles include the cost of oncological care, and poor infrastructure. In the face of scarce resources, and so many competing priorities, many have been powerless to do much (Lingwood et al. 2008).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree