Delirium and Dementia: Introduction

Diagnosis and management of geriatric patients exhibiting symptoms and signs of impaired cognitive functioning can make a critical difference to their overall health and the ability to function independently. Impaired cognitive function can be acute in onset, or it can be manifest by slowly progressive cognitive impairment. The major causes of impaired cognition in the geriatric population are delirium and dementia. As more people live into the tenth decade of life, the chance that they will develop some form of dementia increases substantially. Community-based studies report a prevalence of dementia as high as 47% among those 85 years of age and older. Prevalence rates are, however, highly dependent on the criteria used to define dementia (Mayeux, 2010). Between 25% and 50% of older patients admitted to acute care medical and surgical services are delirious on admission or develop delirium during their hospital stay. In nursing homes, 50% to 80% of those older than age 65 years have some degree of cognitive impairment. Delirium is often superimposed on dementia in both hospital and community settings, can persist for days to weeks after discharge from an acute hospital, and is a risk factor for functional decline and mortality. Both dementia and delirium are associated with high health-care costs (Okie, 2011).

Misdiagnosis and inappropriate management of conditions leading to confusion in geriatric patients can cause substantial morbidity among the patients, hardship for their families, and excess health-care expenditures. This chapter provides a practical framework for diagnosing and managing geriatric patients who demonstrate “confusion” or signs of cognitive impairment. We focus on the most common causes of confusion in the geriatric population—delirium and dementia—although a variety of other disorders can cause the same or similar signs.

Imprecise definition of the abnormalities of cognitive function in older patients labeled as “confused” has led to problems in diagnosis and management. Descriptions such as impairment of cognitive function or cognitive impairment coupled with careful documentation of the timing and nature of specific abnormalities provide more precise and clinically useful information. Such documentation is best accomplished by screening and a thorough mental status examination, if indicated.

Screening for delirium can be accomplished with the confusion assessment method (CAM). The Mini-Cog is useful in screening for cognitive impairment and dementia. Both of these screening tests are discussed later in the chapter.

A thorough mental status examination has several basic components that are essential in diagnosing dementia, delirium, or other syndromes (Table 6–1). The examiner should focus on each of these components in a systematic manner. Recording observations in each area facilitates recognizing and evaluating changes over time. Standardized and validated measures of cognitive function (see Appendix) should be used in diagnosis and subsequent monitoring. Several factors may, however, influence performance and interpretation of standard mental status tests, such as prior educational level, primary language other than English, severely impaired hearing, or poor baseline intellectual function. Thus, scores on these tests should not be used to replace a more comprehensive examination such as that in Table 6–1.

State of consciousness General appearance and behavior Orientation Memory (short- and long-term) Language Visuospatial functions Executive control functions (eg, planning and sequencing of tasks) Other cognitive functions (eg, calculations, proverb interpretation) Insight and judgment Thought content Mood and affect |

Important information can be gleaned unobtrusively from simply observing and interacting with the patient during the history. Is the patient alert and attentive? Does the patient respond appropriately to questions? How is the patient dressed and groomed? Does the patient repeat herself or give an imprecise social or medical history, suggesting memory impairment? Orientation, insight, and judgment can sometimes be assessed during the history as well.

Questions relating to specific areas of cognitive functioning should be introduced in a nonthreatening manner, because many patients with early deficits respond defensively. Each of the three basic components of memory should be tested: immediate recall (eg, repeating digits), recent memory (eg, recalling three objects after a few minutes), and remote memory (eg, ability to give details of early life). Language and other cognitive functions should be carefully evaluated. Is the patient’s speech clear? Can the patient read (and understand) and write? Does there seem to be a good general fund of knowledge (eg, current events)? Other cognitive functions that can be tested easily include the ability to perform simple calculations (eg, one that relates to making change while shopping) and to copy diagrams. The ability to interpret proverbs abstractly and to list the names of animals (listing 12 names in 1 minute is normal) is a sensitive indicator of cognitive function and is easy to test.

Judgment and insight can usually be assessed during the examination without asking specific questions, although input from family members or other caregivers can be helpful, and is sometimes necessary. Any abnormal thought content should also be noted during the examination; bizarre ideas, mood-incongruent thoughts, and delusions (especially paranoid delusions) may be present in older patients with cognitive impairment and are important both diagnostically and therapeutically. Observations during the examination may also detect abnormalities of executive control. Executive function involves the planning, sequencing, and execution of goal-directed activities. These functions are critical to the ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Screening tests for executive dysfunction include a clock-drawing test, which is a component of the Mini-Cog (see later in this chapter).

Throughout the examination, the patient’s mood and affect should be assessed. Depression, apathy, emotional liability, agitation, and aggression are common in older patients with cognitive impairment (Lyketsos et al., 2002), and failure to recognize these abnormalities can lead to improper diagnosis and management. In some patients—such as those who are very intelligent or poorly educated, or have low intelligence, as well as those in whom depression is suspected—more detailed neuropsychological testing by an experienced psychologist is helpful in precisely defining abnormalities in cognitive function and in differentiating between the many and often interacting underlying causes.

Differential Diagnosis

The causes of impaired cognitive function in the geriatric population are myriad. The differential diagnosis in an older patient who presents with confusion includes disorders of the brain (eg, stroke, dementia), a systemic illness presenting atypically (eg, infection, metabolic disturbance, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure), sensory impairment (eg, hearing loss), and adverse effects of a variety of drugs or alcohol.

Similar to many other disorders in geriatric patients, cognitive impairment often results from multiple interacting processes rather than a single causative factor. Accurate diagnosis depends on specifically defining abnormalities in mental status and cognitive function and on consistent definitions for clinical syndromes. Disorders causing confusion in the geriatric population can be broadly categorized into three groups:

Acute disorders usually associated with acute illness, drugs, and environmental factors (ie, delirium)

More slowly progressive impairment of cognitive function as seen in most dementia syndromes

Impaired cognitive function associated with affective disorders and psychoses

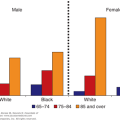

Older patients have often been labeled “senile” because they are unable to answer a question or because they are not given adequate time to respond. Other age-associated disorders such as impaired hearing and Parkinson disease can also lead to mislabeling an older patient as confused or senile. Old age alone does not cause impairment of cognitive function of sufficient severity to render an individual dysfunctional. Slowed thinking and reaction time, mild recent memory loss, and impaired executive function can occur with increasing age and may or may not progress to dementia. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and cognitive impairment, not dementia (CIND) have been used to describe these deficits. Just over 20% of people age 71 and older in the United States have cognitive impairment without dementia (Plassman et al., 2008). The definitions, prevalence, prognosis, and treatment of MCI and CIND are being studied actively at the current time. Data suggest that up to 15% to 20% of those diagnosed with MCI or CIND will progress to dementia over the course of a year (Petersen, 2011; Ravaglia et al., 2008; Ries et al., 2008; Sachdev et al., 2012). The therapeutic implications of MCI are subjects of intensive research, but at this time, no intervention has been shown to prevent progression to dementia.

Three questions are helpful in making an accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause(s) of confusion:

Has the onset of abnormalities been acute (ie, over a few hours or a few days)?

Are there physical factors (eg, medical illness, sensory deprivation, drugs) that may contribute to the abnormalities?

Are psychological factors (ie, depression and/or psychosis) contributing to or complicating the impairments in cognitive function?

Delirium

Delirium is an acute or subacute alteration in mental status especially common in the geriatric population. The prevalence of delirium in hospitalized geriatric patients is approximately 15% on admission, and the incidence in this setting may be up to one-third. Delirium may persist for days or weeks and is, therefore, common in post–acute care settings. Many factors predispose geriatric patients to the development of delirium, including impaired sensory functioning and sensory deprivation, sleep deprivation, immobilization, and transfer to an unfamiliar environment.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) defines diagnostic criteria for delirium (Table 6–2). The key features of this disorder include the following:

- Disturbance of consciousness

- Change in cognition not better accounted for by dementia

- Symptoms and signs developing over a short period of time (hours to days)

- Fluctuation of the symptoms and signs

- Evidence that the disturbances are caused by the physiological consequences of a medical condition

|

The disturbances of consciousness and attention, with sudden onset and fluctuating cognitive status, are the major features that distinguish delirium from other causes of impaired cognitive function. Delirium is characterized by difficulty in sustaining attention to external and internal stimuli, sensory misperceptions (eg, illusions), and a fragmented or disordered stream of thought. Disturbances of psychomotor activity (eg, restlessness, picking at bedclothes, attempting to get out of bed, sluggishness, drowsiness, and generally decreased psychomotor activity) and emotional disturbances (eg, anxiety, fear, irritability, anger, apathy) are common in delirious patients. Neurological signs (except asterixis) are uncommon in delirium.

Among hospitalized geriatric patients, many factors are associated with the development of delirium (Inouye and Charpentier, 1996), including:

- Age greater than 80 years

- Male sex

- Preexisting dementia

- Fracture

- Symptomatic infection

- Malnutrition

- Addition of three or more medications

- Use of neuroleptics and narcotics

- Use of restraints

- Bladder catheters

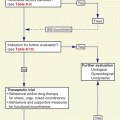

Rapid recognition of delirium is critical because it is often related to other reversible conditions and its development may be a poor prognostic sign for adverse outcomes including nursing home placement and death. CAM is a validated tool to screen for delirium (Inouye et al., 1990). The diagnosis of delirium by the CAM requires the presence of:

- Acute onset and fluctuating course and

- Inattention and

- Disorganized thinking or

- Altered level of consciousness

Differentiating delirium from dementia is important, because the latter is not immediately life threatening, and inappropriately labeling a delirious patient as demented may delay the diagnosis of serious and treatable underlying medical conditions. It is not possible to make the diagnosis of dementia when delirium is present in a patient with previously normal or unknown cognitive function. The diagnosis of dementia must await the treatment of all of the potentially reversible causes of delirium, as discussed later. Table 6–3 shows some of the key clinical features that are helpful in differentiating delirium from dementia. Sundowning is a term that describes an increase in confusion that commonly occurs in geriatric patients, especially those with preexisting dementia, at night. This condition is probably related to sensory deprivation in unfamiliar surroundings (such as the acute care hospital), and patients who sundown may actually meet the criteria for delirium.

Delirium | Dementia |

|---|---|

Marked psychomotor changes (hyperactive or hypoactive, lethargic or agitated) | Generally unchanged psychomotor behavior (patient’s baseline activity) |

Altered and changing levels of consciousness | No change in level of consciousness |

Short attention span | No change in attention span |

Speech is often incoherent | Difficulty finding words or aphasic (in multi-infarct dementia) |

Hallucinations (usually visual) and illusions common | Hallucinations unusual until later stages except in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies |

Sleep-wake cycle disrupted | Sleep may be disturbed, but sleep-wake cycle less commonly affected |

Positive screen on Confusion Assessment Method | Negative screen for delirium Confusion Assessment Method |

Symptoms develop over a short period of time and last days to weeks | Symptoms usually gradual in onset and progress over years |

Symptoms and signs can show marked fluctuation | Symptoms may vary throughout the day, but fluctuation not as prominent |

Generally evidence of an acute illness and/or medication side effect | No evidence of acute illness |

A complete list of conditions that can cause delirium in the geriatric population would be too long to be useful in a clinical setting. Table 6–4 lists some of the common causes of this disorder. Several of them deserve further attention. Each geriatric patient who becomes acutely confused should be evaluated to rule out treatable conditions such as metabolic disorders, infections, and causes for decreased cardiac output (ie, dehydration, acute blood loss, heart failure). The evaluation should include vital signs (including pulse oximetry and a finger-stick glucose determination in diabetics), a careful physical examination, a complete blood count and basic metabolic panel, and other diagnostic tests as indicated by the findings and the patient’s comorbidities.

Metabolic disorders Hypoxia Hypercarbia Hypo- or hyperglycemia Hyponatremia Azotemia Infections Decreased cardiac output Dehydration Acute blood loss Acute myocardial infarction Congestive heart failure Stroke (small cortical) Drugs (see Table 6–5) Intoxication (alcohol, other) Hypo- or hyperthermia Acute psychoses Transfer to unfamiliar surroundings (especially when sensory input is diminished) Other Fecal impaction Urinary retention |

Sometimes this workup is unrevealing. Small cortical strokes, which do not produce focal symptoms or signs, can cause delirium. These events may be difficult or impossible to diagnose with certainty, but there should be a high index of suspicion for this diagnosis in certain subgroups of patients—especially those with a history of hypertension, previous strokes, transient ischemic attacks, or cardiac arrhythmias. If delirium recurs, a source of emboli should be sought, and associated conditions (such as hypertension) should be treated optimally. Fecal impaction and urinary retention, common in geriatric patients in acute care hospitals, can have dramatic effects on cognitive function and may be causes of acute confusion. The response to relief from these conditions can be just as impressive.

Drugs are a major cause of acute and chronic impairment of cognitive function in older patients. Anesthesia poses a special risk. Table 6–5 lists selected drugs that can cause or contribute to delirium. Every attempt should be made to avoid or discontinue any medication that may be worsening cognitive function in a delirious geriatric patient. Environmental factors, especially rapid changes in location (such as being hospitalized, going on vacation, or entering a nursing home) and sensory deprivation, can precipitate delirium. This is especially true of those with early forms of dementia (see next section). Measures such as preparing older patients for changes in location; placing familiar objects in the surroundings; and maximizing sensory input with lighting, clocks, and calendars may help prevent or manage delirium in some patients. A Hospital Elder Life Program has been described that may help prevent delirium and cognitive and functional decline among high-risk older patients in acute hospitals (Inouye et al., 1999; Inouye et al., 2000; see http://hospitalelderlifeprogram.org/public/public-main.php). This program incorporates several strategies for identifying potentially reversible causes of delirium and medical behavioral and environmental interventions for patients who develop delirium and has been shown to be sustainable in a community hospital setting (Rubin et al., 2011).

Analgesics | Cardiovascular |

Narcotic | Antiarrhythmics |

Nonnarcotic | Digoxin |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents | H2 receptor antagonists |

Anticholinergics/antihistamines | Psychotropic drugs |

Anticonvulsants | Antianxiety drugs |

Antihypertensives | Antidepressant drugs Antipsychotics |

Antiparkinsonism drugs | Sedatives/hypnotics |

Alcohol | Skeletal muscle relaxants Steroids |

Dementia

Dementia is a clinical syndrome involving a sustained loss of intellectual functions and memory of sufficient severity to cause dysfunction in daily living. Loss of functional ability due to impaired cognition is the key feature that distinguishes dementia from MCI. Its key features include:

Reversible or partially reversible dementias

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree