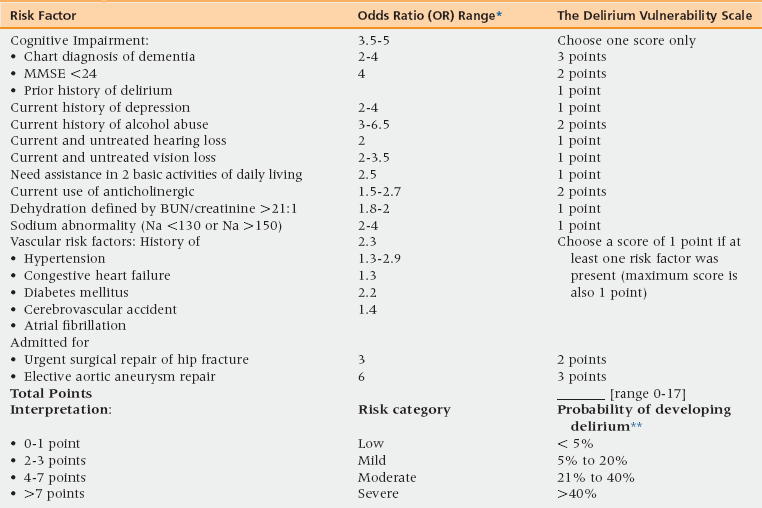

16 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Discuss the definition, the burden, and the pathophysiology of delirium among hospitalized older adults. • Understand the delirium vulnerability-trigger interaction model, use this model to characterize the vulnerability of hospitalized older adults for developing delirium, and identify the precipitant factors that trigger delirium among these vulnerable individuals. • Recognize the importance of using primary prevention to decrease the burden of delirium in hospitalized older adults, and the value of implementing proactive screening to identify at-risk persons at the time of hospital admission. • Discuss the management of delirium in general and delirium-induced agitation in particular. • Describe a multicomponent hospital system to decrease the burden of delirium, and discuss the process of implementing such a program at the reader’s local acute setting. Delirium or acute confusional state is a syndrome characterized by disturbance in consciousness, with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention that occurs over a short period of time and tends to fluctuate over the course of the day.1 This disturbance affects numerous domains of brain function; thus acute brain failure is an accurate descriptive term for delirium. Delirium induces various neuropsychiatric symptoms such as lethargy, aggression, and hallucinations. These symptoms can be used to divide delirium into hypoactive, hyperactive, or mixed types.2,3 Delirium’s neuropsychiatric symptoms are shared across various brain disorders such as dementia, depression, and psychosis. However, the acute and fluctuating nature of symptoms is the main feature differentiating delirium from depression, dementia, and other brain conditions. Box 16-1 summarizes the various categories of delirium neuropsychiatric symptomatology. Studies of patients with delirium suggest that prefrontal cortex, basal forebrain, anterior thalamus, and nondominant parietal and fusiform cortex are involved in inducing delirium symptoms.4–6 At present, stress is considered to be the cornerstone of delirium pathogenesis, leading to metabolic changes that modify the cerebral neurotransmission.7–11 Common stressors include drugs, infection, hypoxia, hypoperfusion, trauma, and surgery,6,9,12 with the final pathway being cholinergic deficiency and dopaminergic excess.9,12 Thus, delirium can be considered a brain maladaptive reaction to acute stress.12 The 2007 National Hospital Discharge Survey conducted by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics estimated 34.4 million hospital discharges. Patients aged 65 and older comprised 37% of all of the hospital discharges and 43% of hospital days.13 The prevalence of delirium among the hospitalized older adults varied from 10% to 52%,14–39 depending on the reason for hospitalization (Table 16-1). The rate increases dramatically among hospitalized older adults with dementia, with delirium occurring in 32% to 86% of this vulnerable population.40 Of patients with delirium, 65% have the hypoactive type, 25% the hyperactive type, and 10% a mixed type.41 TABLE 16-1 Prevalence of Delirium among Hospitalized Older Adults With the aging of the U.S. population, there will be an expected increase in the prevalence of age-related diseases.42 Therefore, we can project an increase in the incidence and prevalence of delirium in the coming years.43 According to the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, hospitalization costs will exceed $1.3 trillion annually by the year 2019 because of the aging population.44 The health care system is currently spending between $38 and $152 billion annually in delirium-related costs,45 and with the rise in aging-related diseases, this expenditure is likely to go up.43 Delirium in the elderly increases the risk of death.46–48 According to one study, the risk odds ratio (OR) of mortality for hospitalized patients with delirium, compared with nondelirious controls, have a higher risk of death (38% versus 27%; odds ratio [OR] 1.95; confidence interval [CI]: 1.51-2.52).46 Patients with delirium are also at an increased risk of institutionalization (33.4% versus 10.7%; OR 2.41; 95% CI: 1.77-3.29).46 These associations are independent of age, gender, comorbidity, severity of illness, and preexisting dementia. Coexistence of delirium with dementia increases the risk of rehospitalization and admission to long-term care compared to patients with dementia or delirium alone.40 Delirium among hospitalized older adults is the result of a complex interaction between various degrees of insult severity and different levels of patient’s vulnerability.49 This vulnerability-trigger interaction is responsible for the wide range (10% to 86%) of delirium prevalence rates reported among hospitalized older adults. Finding a single factor responsible for the onset of delirium is rare. By using the vulnerability-trigger interaction model, clinicians can categorize the contributing factors of delirium into two groups. First is the cluster of predisposing or vulnerability factors (Table 16-2). Second is the cluster of precipitating or trigger factors (Table 16-3). However, some factors can act as both precipitating and predisposing. A common example of such a dual factor is a drug with anticholinergic properties. The delirium vulnerability of an older female adult who is taking anticholinergic drugs such as oxybutinine for urine incontinence is already high. Prescribing a sleeping pill such as diphenhydramine with anticholinergic properties to manage her postoperative sleep problem might be the factor that tips her into delirium during her hospital admission for elective knee replacement. TABLE 16-2 Predisposing Factors for Delirium among Older Adults Hospitalized for a Medical or a Surgical Illness MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination. *OR estimates were based on review of the literature. **Delirium probability estimates for each risk category were based on a literature review17,20,21,24,26,29,31,36-40,52,54,66,75-79 and the authors’ clinical and research experiences. The delirium vulnerability scale has not been validated in a prospective cohort study. TABLE 16-3 Precipitating Factors for the Development of Delirium during Hospitalization for Medical or Surgical Illness36,49,58,78,79 BP, Blood pressure; Hct, hematocrit; SBP, systolic blood pressure. Because of the important role that anticholinergic medications play in the development of delirium as predisposing and precipitating factors, we have summarized the most common anticholinergic medications that are used in older adults (Table 16-4). The concept of total anticholinergic burden has been used to reflect the cumulative anticholinergic activities of all medications taken by an individual patient.50,51 Thus both a single drug with strong anticholinergic properties and a combination of multiple drugs with a relatively small anticholinergic effect might lead to the development of delirium in older adults.52-55 TABLE 16-4 Medications with Central Anticholinergic Activity*

Delirium

Definition and pathogenesis of delirium

Prevalence and impact of delirium

Setting and Population

Delirium Prevalence Range

Older adults hospitalized for medical illness14-21

11% to 41%

Postoperative: Older adults undergoing surgical repair of hip fracture22–25

40% to 52%

Postoperative: Older adults undergoing elective major noncardiac surgery26–31

10% to 39%

Postoperative: Older adults undergoing cardiac surgery32–39

13% to 44%

Risk factors and precipitating factors

Precipitating Factor

Odds Ratio (OR)

Use of physical restraints

4.4

Malnutrition

4

Using more than three new medications during hospitalization

2.9

Use of bladder catheterization

2.4

Exposed to any iatrogenic event

1.9

Intraoperative hypotension (at least 31% drop in mean perioperative BP or a SBP ≤80 mmHg

1.4

Postoperative Hct <30%

1.7

Untreated postoperative pain

5.4-9

Use of anticholinergic drug

1.5-2.7

Score = 3

High Anticholinergic Activity

Score = 2

Moderate Anticholinergic Activity

Score = 1

Mild Anticholinergic Activity

Amitriptyline

Amantadine

Alverine

Amoxapine

Belladonna

Alprazolam

Atropine

Carbamazepine

Atenolol

Benztropine

Cyclobenzaprine

Bupropion

Brompheniramine

Cyproheptadine

Captopril

Carbinoxamine

Loxapine

Chlorthalidone

Chlorpheniramine

Meperidine

Cimetidine

Chlorpromazine

Methotrimeprazine

Clorazepate

Clemastine

Molindone

Codeine

Clomipramine

Oxcarbazepine

Colchicine

Clozapine

Pimozide

Diazepam

Darifenacin

Digoxin

Desipramine

Dipyridamole

Dicyclomine

Disopyramide

Dimenhydrinate

Fentanyl

Diphenhydramine

Furosemide

Doxepin

Fluvoxamine

Flavoxate

Haloperidol

Hydroxyzine

Hydralazine

Hyoscyamine

Hydrocortisone

Imipramine

Isosorbide ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access