Chapter 18

Delirium

Introduction

Delirium affects at least 10% of older patients in the ED and up to 30% of older medical inpatients. As well as being very common, it is associated with multiple adverse outcomes. Delirium is greatly under detected in the ED and in acute wards ((1, 2)), and care is often suboptimal.

This chapter focuses on the assessment and management of acute delirium in older patients, both on initial presentation to the ED and on the ward. Other causes of behavioural disturbance in the older patient will be considered in the section titled Differential Diagnosis’. This chapter also aims to provide general guidance on the use of legislation to safely manage delirious patients who lack capacity regarding their healthcare decisions, although exact laws vary depending on location.

Definition

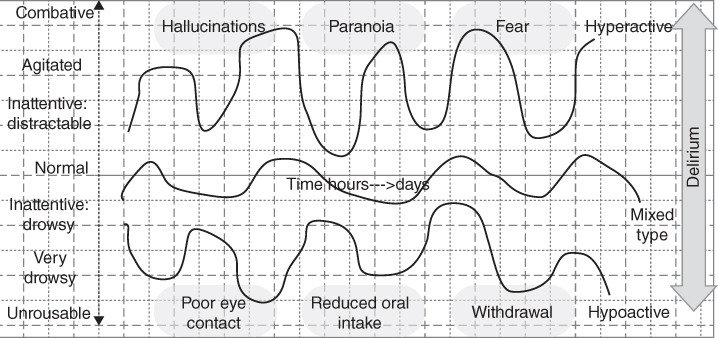

Figure 18.1 A graphical depiction of the different types of delirium.

Background

Delirium in older patients is linked with poor outcomes. Delirious patients are twice as likely to die, have longer hospital admissions and are more likely to develop dementia or require institutional care on discharge. Failure to detect delirium in the ED is associated with increased mortality and is an independent predictor of increased hospital stay (3–6).

Many patients who experience an episode of delirium never return to their cognitive baseline. In addition, a significant proportion of patients can recall the experience of acute delirium, and 70–80% of these patients experience significant distress as a result of these recollections (7, 8).

Risk factors for delirium

- Increasing age

- Male sex

- Multiple comorbidities

- Pre-existing dementia

- Previous episode of delirium

- History of stroke or other neurological disorder

- Depression

- Current or past alcohol abuse

- Chronic hepatic or renal impairment

History

Most patients with delirium will be unable to give a structured history. However, time spent observing and, where possible, talking with delirious patients is an essential part of assessment to document the level of arousal and the nature of their disturbed mental state and provide a baseline for comparison against later assessments.

Some patients will be able to provide information relating to their symptoms and presentation; however, this will differ depending on individual cases.

Collateral history as early as possible is essential in patients with suspected delirium. It should aim to establish the following: (see also Table 18.1).

- Is the patient more confused than normal?

- Has there been an acute change in cognition or level of arousal?

- Do the symptoms fluctuate?

- Have there been any associated symptoms suggestive of a precipitant illness?

- Have there been any changes in medication?

- Have the symptoms been present for hours/days/weeks or months?

- Was there evidence of background cognitive impairment before this acute change?

Table 18.1 Taking an informant history for a patient with delirium

| Question | Reason you are checking | Why it is important |

| Have they had any recent illnesses, accidents or falls or complained of any particular problems? | Searching for precipitant: e.g. infection/head injury | Identifying and treating potential precipitating causes |

| Have had contact with the health services (e.g. primary care physician)? If so, why? | Searching for precipitant: e.g. new medication, inter-current illness | Primary care physicians can provide useful collateral information |

| Have their bowels and bladder been working normally? | Searching for precipitant: e.g. constipation, retention and UTI | Identifying and treating potential precipitating causes. E.g. constipation and urinary retention commonly co-exist |

| Have they been eating and drinking normally? | Searching for precipitant: e.g. dehydration Identifying possible consequence: e.g. reduced oral intake secondary to delirium | Reduced oral intake and dehydration can be a cause and a consequence of delirium. Nutritional status should be actively checked |

| Is there any change in their sleeping pattern? | Searching for precipitant/establishing diagnosis: sleep disturbance can precipitate delirium and also indicate delirium | Optimising sleep hygiene and establishing a routine can help treat delirium and reduce its chance of recurring |

| Do they have a walking aid? | Searching for precipitants: e.g. immobility Identifying possible consequences: falls | Immobility can precipitate or worsen delirium and patients should be encouraged to mobilise safely; delirious patients are at increased risk of falling and this needs to be considered when planning their care |

| Do they have hearing or visual aids? | Searching for precipitants: e.g. sensory impairment | Sensory impairment can precipitate or worsen delirium; ensuring patients can see and hear can improve recovery from delirium |

| What medicines are they on? | Searching for precipitant: e.g. medication. Ensuring important medications are not omitted | Intercurrent illness or increasing age may affect drug metabolism leading to adverse effects |

| Have their medicines been changed? | Searching for precipitant: e.g. new medication | Starting or stopping medications suddenly can precipitate delirium |

| Do they manage their own pills? | Searching for precipitant: e.g. medication error Establishing cognitive baseline | This may increase the risk of a medication error; it is also a helpful introduction question to discussing the patient’s normal cognitive abilities |

| Have they had any memory problems in the past? | Establishing cognitive baseline | Patients with dementia are at increased risk of delirium and need to be regularly screened when in hospital |

| Do they seem more confused, upset, agitated or drowsy than normal? | Establishing diagnosis: recent change in cognition | Differentiates delirium from dementia |

| Has this happened before? If so, what happened? | Identifying potential tendency to delirium | Patients with prior delirium are at increased risk of developing it again and need regular screening |

| Do they sometimes seem OK and other times become confused? | Establishing diagnosis: fluctuation | Differentiates delirium from dementia |

| Any sign of them hearing or seeing things that are not real? | Establishing diagnosis: Identifying hallucinations | Hallucinations are a common symptom of delirium and can be very distressing |

| Were they like this last week? How about the week before that? (and so on) | Establishing diagnosis: timescale (typically hours-days-weeks rather than months-years) | Differentiates delirium from dementia |

| Have they been distressed, e.g. by not understanding what is happening to them? | Managing symptoms: detecting distress | Distress is very common in delirium but is greatly underestimated |

| Have they shown any signs of having hallucinations, or suspicious beliefs? | Managing symptoms: detecting psychosis | Psychosis is common in delirium and is an important cause of distress. It is often undetected |

Almost any medical condition or drug can lead to delirium. In addition, physiological disturbance from medical conditions can directly lead to delirium. Box 18.3 contains a list of precipitants to consider early in the assessment.

Differential diagnosis

Delirium is generally readily distinguished from other mental disorders because of its acute onset and fluctuating course. However, a clear informant history is not always available. The following conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree