Epidemiology

Traditionally, the incidence of Cushing’s syndrome was reported as 2–4 per million per year. However, Cushing’s syndrome may be more common than previously thought. An unexpectedly high incidence of unrecognized Cushing’s syndrome has been demonstrated in high-risk populations, for example 0.5–1% of hypertensive patients, 2–3% of patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and 3–5% of obese, hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is more common in females.

Clinical presentations

Many features of Cushing’s syndrome, such as weight gain, fatigue, depression, hirsutism, acne and menstrual abnormalities, are also common in the general population, and the spectrum of clinical presentation is broad. Therefore confirmation of the diagnosis may be delayed until 1–2 years after the onset of the symptoms. A review of old photographs of the patient may be useful as those with Cushing’s syndrome usually have progressive clinical features.

Some features of Cushing’s syndrome that are common in the general population are more likely to be due to Cushing’s syndrome if the onset is at a younger age. These include:

- type 2 diabetes mellitus

- hypertension

- osteoporosis

- thin skin.

Signs that are more discriminatory (although not unique to Cushing’s syndrome) include:

- easy bruising

- proximal muscle weakness

- facial plethora

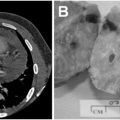

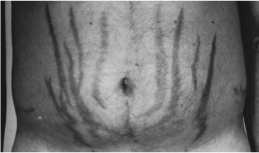

- reddish-purple striae on the abdomen, breast or thighs more than 1 cm wide (Fig. 16.1)

- weight gain with decreasing growth velocity in children.

Figure 16.1 Abdominal striae in a patient with Cushing’s syndrome.

Patients with pseudo-Cushing’s syndrome seldom have easy bruising, thin skin or proximal muscle weakness.

Other features seen in Cushing’s syndrome that may have other causes include:

- reduced concentration, impaired memory, psychosis

- reduced libido

- unusual infections

- poor skin healing

- pigmentation (in ACTH-dependent cases)

- hypokalaemia (usually in ACTH-dependent ectopic cases).

Investigations

A thorough history should be taken to exclude exogenous glucocorticoid use causing iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome before performing any biochemical tests.

Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is rare, and conditions such as obesity, depression, diabetes and hypertension are common. Thus the risk of false-positive results following biochemical tests is high. The rate of false-positive cases may be reduced if tests are performed only in patients with a high pre-test probability of having Cushing’s syndrome, i.e. patients with:

- unusual features for their age (see above)

- multiple and progressive signs and symptoms, especially those which best discriminate Cushing’s syndrome (see above)

- adrenal incidentalomas (2–20% prevalence of Cushing’s syndrome)

- children with increasing weight and reducing height percentile.

Initial high-sensitivity tests

The following tests have a sensitivity of more than 90%, and any one of them may be used as the initial test depending on their suitability (some tests are preferred over others in certain situations; see the sections on pitfalls below).

24-Hour urinary free cortisol

Two or three 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC) measurements should be made. Urinary creatinine and volume should also be measured to ensure adequate urine collection over 24 hours.

Pitfalls

UFC measurement is not recommended in patients with renal failure as levels may be falsely low due to reduced glomerular filtration. A high fluid intake (≥5 L per day) may result in false-positive results.

Overnight dexamethasone and low-dose dexamethasone suppression tests

In the overnight test, 1 mg dexamethasone is taken at midnight. If the serum cortisol measured next morning between 8 and 9 a.m. is over 50 nmol/L (failure of suppression), the test is considered abnormal.

In the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST), 0.5 mg is taken at intervals of exactly 6 hours for 48 hours (i.e. at 9 a.m., 3 p.m., 9 p.m. and 3 a.m.). If serum cortisol measured at 9 a.m. on day three (48 hours after the first dose of dexamethasone) is over 50 nmol/L (a failure of suppression), the test is considered abnormal.

Pitfalls

Assays used for serum cortisol in dexamethasone suppression tests measure total cortisol (free and bound to cortisol-binding protein). Oestrogens increase cortisol-binding protein levels and therefore increase total cortisol levels (but not free cortisol levels). They should be stopped for 6 weeks prior to the test as they may result in false-positive results.

Dexamethasone metabolism and clearance may be increased by some drugs (e.g. phenytoin, carba-mazepine, rifampicin). Dexamethasone clearance is decreased in patients with renal or liver failure. Thus simultaneous measurement of cortisol and dexamethasone (if available) in these circumstances is helpful.

Late-night salivary cortisol measurements (if available)

In normal individuals, cortisol falls to very low levels at midnight. In Cushing’s syndrome, there is a loss of normal circadian rhythm. Saliva is collected either into a plastic tube by passive drooling or by placing a cotton pledget (Salivette) in the mouth and chewing for 1–2 minutes. The sample should be collected at home (in a stress-free environment).

Pitfalls

Circadian rhythm may also be blunted in shift-workers. Cigarette smoking should be avoided prior to the collection of salivary cortisol as tobacco contains an inhibitor of 11 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2, an enzyme that metabolizes cortisol.

In patients with normal test results, Cushing’s syndrome is unlikely. However, if signs or symptoms progress, tests may be repeated in 6 months’ time. If any one of the above tests is abnormal, another one or two of the above high-sensitivity tests should be performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree