Surgical management of ovarian cancer requires excellent judgment and mastery of a wide array of procedures. Involvement of a gynecologic oncologist improves outcomes. Staging of apparent stage I disease is important. Minimally invasive techniques provide advantages. Primary debulking surgery provides the best long-term survival of any strategy in advanced ovarian cancer. Aggressive surgical paradigms have the greatest success. Further cytoreductive surgery may be appropriate. Most relapsed patients require management of bowel obstruction at some point. Palliative intervention can enhance quality of life. Surgical correction may extend survival. For end-stage patients with progressive disease, the treating gynecologic oncologist must manage expectations.

Ovarian cancer is a heterogeneous disease requiring a disciplined surgical approach to consistently achieve the best possible outcomes. Epithelial ovarian carcinomas, including the more indolent (borderline) tumors with low malignant potential, comprise 90% to 95% of all cases. Sex cord–stromal tumors and malignant ovarian germ cell tumors are rare. However, surgery plays a critical role in all stages of these various subtypes of ovarian malignancy. Moreover, current surgical techniques and recent innovations also apply to peritoneal and fallopian tube cancers because of their clinical similarities.

Comprehensive surgical management of ovarian cancer involves both knowledge of the disease process and mastery of a wide spectrum of different procedures. A newly diagnosed complex adnexal mass with or without carcinomatosis may be detectable before surgery, but the intended operation often needs to be revised based on frozen section histology or other intraoperative findings. The surgeon must strike the perfect balance between being appropriately aggressive and trying to avoid unnecessary morbidity. Postoperative complications, disease relapse, and symptomatic end-stage sequelae are other common situations that may need to be addressed. Again, the surgeon is often faced with making a difficult decision to intervene or to manage nonsurgically. Because of the complexities of providing longitudinal care for patients with ovarian cancer, better outcomes are reported when a subspecialist is overseeing treatment.

Fewer than half of such patients in the United States and Europe are cared for by a gynecologic oncologist. Instead, most are managed by physicians not necessarily intimately familiar with the interplay between medical and surgical management. However, improvements in overall survival depend on the precise coordination of both forms of treatment. When a gynecologic oncologist is involved, patients are more likely to undergo both primary staging and surgical debulking. Thereafter, additional surgery may need to be considered as part of the therapeutic strategy or for palliative purposes. This article provides a comprehensive review of the surgical management of ovarian carcinoma.

Surgical staging

Typically, an adnexal mass is suspected by symptom history or findings on pelvic examination. Alternatively, it may be discovered by serendipity on sonography or computed tomography (CT) scanning. Proper identification of an ovarian malignancy among patients with a pelvic mass may be aided by imaging characteristics of the mass and the rest of the abdomen, in addition to the preoperative CA125 level. More recently, the human epididymis 4 (HE4) serum marker has been approved for use in helping to effectively triage such patients. The current referral guidelines for a newly diagnosed pelvic mass incorporate several of these features and are listed in Box 1 .

Postmenopausal women

Increased CA125 level

Ascites

Nodular or fixed pelvic mass

Evidence of abdominal or distant metastasis

Premenopausal women

Very increased CA125 level

Ascites

Evidence of abdominal or distant metastasis

Because ovarian cancer is surgically staged, every patient who is taken to the operating room with a suspicious adnexal mass should be consented for comprehensive staging if malignancy is found. Ideally, a physician trained to appropriately stage ovarian cancers, such as a gynecologic oncologist, should perform the operation. Moreover, the operation should take place in a hospital facility that has the necessary support and consultative services (ie, frozen section pathology). When a malignant ovarian tumor is discovered and the appropriate operation cannot be properly performed, a gynecologic oncologist should be consulted during surgery if possible. If immediate consultation is not available, or if the diagnosis is only noted on final pathology, a postsurgical referral is mandatory. In these instances, the gynecologic oncologist needs to make a clinical judgment about whether there is enough information to recommend expectant management or chemotherapy. Alternatively, restaging might be advisable to better define the disease process.

The intent of surgical staging is threefold: (1) to establish a diagnosis; (2) to assess the extent of disease; (3) to remove as much gross tumor as possible. Patients who undergo comprehensive surgical staging to confirm early-stage disease have a better prognosis than patients who are thought to have early-stage disease but do not undergo comprehensive surgical staging, presumably because occult metastatic disease is not detected.

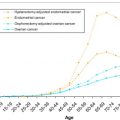

Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

The consistent inability to reliably detect epithelial ovarian carcinoma before metastasis has occurred has been an ongoing disappointment. Routine screening has not been shown to improve early detection or reduce mortality in either the high-risk or general populations. As a result, only one-quarter of newly diagnosed women have disease confined to the ovary. Comprehensive staging results in a shifting of patients with subclinical metastases from early-stage to advanced-stage disease with an improved median survival for both groups. In addition, treatment-related side effects or complications may be avoided. Patients with accurately defined surgical stage I disease may not require any additional treatment, or may safely receive less chemotherapy than otherwise would be the case in inadequately staged patients. When occult stage III disease is detected, patients may be treated more aggressively with intraperitoneal chemotherapy, or be eligible for clinical trial participation.

A conceptual understanding of the spread pattern of epithelial ovarian cancer is valuable to help guide the surgical staging procedure. Epithelial ovarian cancer arises within the ovarian surface epithelium, grows focally, and ultimately breaches the ovarian capsule to metastasize by exfoliation or via the abdominal/pelvic lymphatic system. Peritoneal fluid flows in a clockwise fashion; thus, cancer cells shed into the fluid initially implant throughout the pelvis and right paracolic gutters, across the diaphragm, and on the small or large intestine. Lymphatic spread to the pelvic and para-aortic regions is also commonplace.

Surgical staging for ovarian carcinoma has historically been performed through an abdominal incision that allows exposure of the entire abdomen. On entry into the peritoneal cavity, ascites is aspirated for cytology if present. If there is no ascites, cytologic washings of the pelvis and paracolic gutters are obtained. A total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is performed in most patients. The contents of the peritoneal cavity, including all organs and peritoneal surfaces, are systematically inspected, and any suspicious-appearing areas are biopsied. Unless these areas are confirmed on frozen section to show malignancy, an omentectomy and peritoneal biopsies are performed.

Suspicious lymph nodes should be excised and sent for frozen section; if negative for malignancy, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy should be performed to exclude microscopic disease. Even when only 1 ovary is grossly involved, the frequency of having only contralateral nodal metastases ranges from 10% to 30%. Chan and colleagues retrospectively analyzed 6686 women with clinical stage I ovarian cancer between 1988 and 2001, observing that most women with stage I epithelial ovarian cancers who underwent lymphadenectomy had a significant improvement in survival. Moreover, the extent of lymphadenectomy (0 nodes, less than 10 nodes, and 10 or more nodes) significantly increased the survival rates from 87% to 92% to 94%, respectively. Because nodal metastases are common above the inferior mesenteric artery, the para-aortic lymphadenectomy should be performed up to the level of the left renal vein.

The importance of a comprehensive initial surgical procedure was first shown by a multicenter national trial in which 100 patients with apparent early-stage disease underwent surgical restaging. Before referral, only 25% of patients had an initial surgical incision that was adequate to allow complete examination of the pelvis and abdominal cavity. One-third of patients were found to have more advanced disease at the second surgery. Furthermore, histologic grade was a significant predictor of occult metastasis: 16% of patients with grade 1 tumors were upstaged, compared with 46% with grade 3 disease. After thorough surgical evaluation, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system is applied to guide adjuvant therapy decisions ( Table 1 ).

| Stage | Surgical-Pathologic Findings |

|---|---|

| IA | Growth limited to 1 ovary |

| IB | Growth limited to both ovaries |

| IC | Tumor limited to 1 or both ovaries, but with disease on the surface of 1 or both ovaries; or with capsule(s) ruptured; or with malignant ascites or positive peritoneal washings |

| IIA | Extension and/or metastases to the uterus and/or tubes |

| IIB | Extension to other pelvic tissues |

| IIC | Tumor limited to the genital tract or other pelvic tissues, but with disease on the surface of 1 or both ovaries; or with capsule(s) ruptured; or with malignant ascites or positive peritoneal washings |

| IIIA | Tumor grossly limited to the true pelvis with negative nodes, but with histologically confirmed microscopic seeding of abdominal-peritoneal surfaces |

| IIIB | Abdominal implants less than 2 cm in diameter with negative nodes |

| IIIC | Abdominal implants at least 2 cm in diameter and/or positive pelvic, para-aortic, or inguinal nodes |

| IV | Distant metastases, including malignant pleural effusion or parenchymal liver metastases |

Comprehensively staged women with stage IA/IB grade 3 disease or stage IC or greater are typically treated with platinum-based adjuvant therapy. Combining the results of 2 large European trials, patients with stage IA and IB grades 2 and 3, stage IC, and stage II who received adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery had an improved survival compared with patients randomly assigned to observation. However, in an analysis of one of the studies, only the incompletely staged patients benefited. Chan and colleagues further showed the value of comprehensive staging in an exploratory analysis of 427 patients prospectively randomized to 3 or 6 cycles of chemotherapy, observing that only those patients having tumors with serous histology derived any benefit from the additional 3 courses of treatment. Thus, comprehensive surgical staging of apparent early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer is critically important to accurately define the extent of disease and appropriately guide postoperative therapy.

Minimally Invasive Staging

Minimally invasive surgery has revolutionized much of gynecologic oncology. However, because most patients with ovarian cancer are diagnosed with advanced disease, the usefulness of this technology has not been as profound as in cervical or endometrial cancer. In addition, the treating gynecologic oncologist may have other concerns ( Box 2 ). As a result, the current literature defining the role of laparoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer is limited to case reports, case series, and cohort studies.

Inability to fully explore the abdomen

Risk of intraoperative rupture

Port-site tumor implantation

One disadvantage of minimally invasive surgery is the inability to fully explore the abdomen in search of tumor implants. There are inherent limitations in accessing the entire peritoneal cavity without a large vertical incision, no matter what other approach is used. In one preliminary analysis, Chi and colleagues showed that patients with apparent stage I ovarian or fallopian tube cancer could safely and adequately undergo laparoscopic surgical staging. They reported no differences in omental specimen size or number of lymph nodes removed. Estimated blood loss and hospital stay were also lower for laparoscopy, but operating time was longer. Overall, the limited data suggest equal efficacy of laparoscopy compared with laparotomy in both early and advanced-stage ovarian cancer. Robotic assistance has also been reported to facilitate comprehensive staging.

Laparoscopic or robotic surgery is postulated to increase the risk of intraoperative rupture of an ovarian cystic mass. The clinical relevance of intraperitoneal spillage is controversial, but this is often the event that triggers the indication for adjuvant chemotherapy when it might not otherwise have been required. Most adnexal masses can be safely detached, placed intact within a specimen retrieval bag, drained or morcellated at the abdominal wall, and removed from a trocar site without spillage. Removal of any suspicious mass without enclosure in a specimen bag is inadvisable because of the possibility of seeding the subcutaneous tissues.

Although clinically relevant, the rate of port-site tumor implantation after laparoscopic procedures in women with malignant disease is low. It usually occurs in the setting of synchronous, advanced intra-abdominal or distant metastatic disease. The presence of port-site implantation is a surrogate for advanced disease and should not be used as an argument against laparoscopic surgery in gynecologic malignancies.

Borderline Tumors

Although formally categorized under the umbrella of epithelial ovarian cancers, low malignant potential (LMP) or borderline tumors have a more indolent biologic behavior. Comprehensive surgical staging of these patients has limited value overall, because most tumors are stage I. Even when stage III microscopic noninvasive implants or nodal metastases are detected, the information is of prognostic value only and adjuvant chemotherapy is not recommended. Thus, routine pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection is not necessary in most women with proven ovarian borderline tumors. In summary, when a definitive diagnosis is confirmed, no additional staging is required.

However, invasive carcinoma may not be detected until final pathologic review. About 25% to 30% of patients with an intraoperative frozen section diagnosis of a borderline tumor are ultimately diagnosed with an invasive cancer after additional sectioning. Nonserous tumors are more likely to be misinterpreted. Because of the uncertainty of intraoperative diagnosis, in most circumstances these tumors should be staged as indicated for epithelial ovarian carcinoma.

Rare Ovarian Tumors

Sex cord–stromal, malignant ovarian germ cell tumors and infrequent epithelial types such as mucinous or clear cell carcinomas have unique biologic behaviors that differ from the more common epithelial variants. Although most of the standard staging procedures apply to rare tumors, lymphadenectomy has limited value overall. Lymph node metastases in ovarian sex cord–stromal tumors and mucinous ovarian cancers are so rare that lymphadenectomy may be safely omitted when staging such patients. Because of the chemoresistance of clear cell carcinomas, detection of nodal metastases is often of prognostic value, but does not necessarily lead to a clinical benefit. Moreover, because of unique tumor dissemination patterns, lymphadenectomy is most important for dysgerminomas, whereas only staging peritoneal and omental biopsies are of importance for yolk sac tumors and immature teratomas.

Fertility-sparing Surgery

Approximately 10% of epithelial ovarian cancers develop in women younger than 40 years of age, suggesting that fertility-sparing surgery may need to be considered in selected patients. When the cancer seems confined to 1 ovary, especially if it is low grade, it is appropriate to modify the staging procedure by leaving the uterus and the uninvolved ovary in place for younger women who wish to preserve fertility. Surgical staging otherwise proceeds as described. Although many patients are upstaged, those with surgical stage I disease have an excellent long-term survival with unilateral adnexectomy. Preserving the uterus and contralateral ovary does not seem to compromise the chances of cure. In some cases, postoperative chemotherapy may be required, but patients usually retain their ability to conceive and ultimately carry a pregnancy to term.

Fertility-sparing management of borderline tumors with cystectomy or unilateral adnexectomy may also be appropriate for motivated, reproductive-aged women. Preservation of the contralateral adnexa increases the risk of recurrence, but surgical resection is usually curative. Unilateral adnexectomy may also be considered for patients with sex cord–stromal ovarian tumors in the absence of obvious disease spread to the uterus. Most such tumors turn out to be stage I. Because of the characteristic young age of women diagnosed with malignant ovarian germ cell tumors, fertility-sparing surgery is the norm and does not adversely affect survival.

Tumor debulking

Ovarian cancer is often portrayed as the disease that whispers because it does not present with dramatic bleeding, excruciating pain, or an obvious lump. Instead, the typical symptoms tend to be indolent. Patients and their health care providers often attribute such nonspecific changes to menopause, aging, dietary indiscretions, stress, depression, or functional bowel problems. Frequently, women are medically managed for indigestion or other presumed ailments without having a pelvic examination. As a result, substantial delays before diagnosis are common. Two-thirds of women who are newly diagnosed with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer still present, as they always have, with advanced disease typically characterized by ascites, carcinomatosis, and omental caking ( Fig. 1 ).

Procedures such as radical pelvic surgery, bowel resection, and aggressive upper abdominal surgery are commonly required to achieve optimal cytoreduction. Recent evidence suggests that metastatic ovarian cancers, like other solid tumors, contain a small subpopulation of highly specialized stem cells with self-renewal capacity and the potential to reconstitute the cellular heterogeneity of a tumor. Ovarian cancer stem cells are thought to be responsible for tumor initiation, maintenance, and growth. Ineffective targeting of this cell population is responsible for the therapeutic failures and tumor recurrences currently observed.

The elimination of potentially chemoresistant cells is one presumed benefit of surgical cytoreduction. The probability of spontaneous mutations to drug-resistant phenotypes increases as tumor size and cell numbers increase according to the Goldie and Coldman hypothesis. Instinctually, cytoreductive surgery should allow removal of existing resistant tumor cells and decrease the spontaneous development of additional resistant cells. Several supportive, but mostly theoretic, additional arguments have been proposed to justify the biologic plausibility of debulking ( Box 3 ).

- •

Removing large necrotic masses promotes drug delivery to smaller tumors with good blood supply.

- •

Removing resistant clones decreases the likelihood of early-onset drug resistance.

- •

Tiny implants have a higher growth fraction that should be more chemosensitive.

- •

Removing cancer in specific locations, such as tumors causing a bowel obstruction, improves the patient’s nutritional and immunologic status.

Removal of bulky tumors as part of cancer treatment is an easy concept for patients and their families to understand. The clinical benefits of debulking have been harder to prove. Within the broader field of oncology, the aggressive surgical approach to widely metastatic disease is unique to ovarian cancer. Patients seem to benefit from 1 maximal debulking attempt, but the timing of the procedure and what defines a success have become increasingly controversial.

Primary Debulking

Joe V. Meigs, a gynecologic surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital, initially described ovarian tumor debulking in 1934. However, the concept was not validated until the mid-1970s. Case series and other retrospective data rapidly accrued thereafter to further establish primary cytoreductive surgery as the de facto standard of care.

The success of the operation depends on numerous factors, including patient selection, tumor location, and surgeon expertise. To achieve a survival benefit, an optimal result was initially defined as no residual tumors individually measuring more than 2 cm in size. For purposes of uniformity, the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) redefined optimal debulking as residual implants less than or equal to 1 cm. For the past few decades, this criterion has served as the benchmark of success. Patients undergoing primary optimal cytoreductive surgery (≤1 cm residual disease), followed by intraperitoneal platinum-based chemotherapy have a median overall survival of 66 months, which is the longest duration ever reported in a phase III study. The level of success achieved in this GOG trial (protocol #172) is currently the gold standard for comparisons with any other sequence of treatment.

Despite the accumulated evidence supporting the importance of primary debulking, it remains controversial whether the better outcome is caused by the surgeon’s technical proficiency or some ill-defined, intrinsic feature of the cancer that makes the tumor implants easier to remove. In general, extensive upper abdominal disease strongly indicates aggressive tumor biology. Although this is a common location of unresectable disease, optimal debulking may still be achieved in many patients by performing ultraradical procedures, such as splenectomy ( Fig. 2 ) or diaphragmatic resection. However, it is still unclear what impact ultraradical techniques have on quality of life and morbidity. Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness of this approach has not been investigated. Although these points should be prospectively studied, survival rates have been shown to improve accordingly when the surgical paradigm is revised to a more aggressive philosophy incorporating these and other radical techniques. Patients referred to specialized centers where such radical procedures are commonly performed may anticipate higher rates of optimal debulking and improved survival, without additional surgery necessarily leading to increased major morbidity.

One valid criticism of cytoreductive surgery is the biased, subjective assessment of gross residual disease by the surgeon at the completion of the operation. Because of tissue induration, inadequate exploration, radiologist overestimation, or other factors, inaccuracies of residual tumor size are common. Perhaps because of the inability to reliably quantify the remaining disease, a recent subanalysis of accumulated data from several prospective GOG trials showed that patients with residual disease of 0.1 to 1.0 cm had marginally improved overall survival compared with patients with greater than 1-cm residual disease for stage III ovarian cancer and no improvement in those with stage IV disease. Large survival benefit was only achieved with complete resection to microscopic residual disease.

Based on these findings and other similar reports, there is a growing consensus that optimal cytoreduction should be defined using a more stringent criterion. Thus, the current goal of primary debulking is to achieve complete resection with no residual disease. Raising the standard for surgical success accordingly decreases the proportion of patients with stage III to IV ovarian cancer in which this redefined optimal result can be accomplished. For advanced disease, reports range from 15% to 30%. However, the clinical benefits are substantial. Chi and colleagues analyzed a prospectively kept database for outcomes of 465 women with stage IIIC ovarian cancer who underwent primary cytoreductive surgery. They observed a median overall survival of 106 months for patients with no gross residual disease, 66 months for those with disease less than or equal to 0.5 cm, 48 months with 0.6 to 1.0 cm residual disease, and 33 to 34 months for greater than 1 cm residual disease. As suggested by these data, although complete resection is often not feasible, cytoreduction to as little residual tumor as possible should always be the focus of aggressive surgical efforts, because each incremental decrease in residual disease less than 1 cm may be associated with an incremental improvement in overall survival.

Even when successful, the disadvantage of radical cytoreductive surgery is that it may result in a prolonged postoperative recovery that is fraught with complications. The initiation of chemotherapy may be delayed, or postponed indefinitely. Special caution is indicated for women aged 75 years or older, especially in the presence of other significant comorbidities. These patients in particular have an increased 30-day mortality. When an optimal result is not possible, the surgical approach should be limited in scope to avoid unnecessary postoperative morbidity.

Such patients may benefit from attempted cytoreduction by minimally invasive techniques. Recently, laparoscopic and robotic-assisted debulking of advanced ovarian cancer have each been reported with minimal morbidity. Although not often feasible because of the disease distribution, such techniques may be warranted in selected circumstances and may be preferable to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT).

Interval Debulking

Preoperative CA125 levels, CT scans, and physical examinations are often not reliable to predict patients who can be optimally debulked. As a result, many patients with advanced ovarian cancers who are taken for surgery cannot be completely resected. Invariably, the final determination cannot be made until abdominal exploration.

Two phase III trials were conducted to determine whether a second interval debulking procedure was worthwhile after an unsuccessful initial attempt followed by a few courses of chemotherapy. A multicenter trial conducted in Europe found a 6-month median survival advantage in patients who were reexplored after 3 cycles of chemotherapy. In contrast, no survival advantage was found when a similar study was conducted in the United States. These conflicting reports are most easily explained by clarifying who performed the first surgery.

In the US trial, virtually all patients had their initial attempt by a gynecologic oncologist, unlike the European study in which few had their first surgery performed by a subspecialist. Thus, interval debulking seems to yield benefit only among patients whose primary surgery was not performed by a gynecologic oncologist, if the first try was not intended as a maximal resection of all gross disease, or if no upfront surgery was performed.

Some patients are too medically ill to initially undergo any type of upfront abdominal operation, whereas others have disease that is too extensive to be resected by an experienced ovarian cancer surgical team. In these circumstances, NACT is routinely used, ideally after the diagnosis has been confirmed by paracentesis, CT-guided biopsy, or laparoscopy. Following 3 to 4 courses of treatment, the feasibility of surgery can be reassessed. In some series, NACT followed by interval debulking has shown comparable survival outcomes with those reported for primary surgery. Fewer radical procedures may be required, the rate of achieving minimal residual disease may be higher, and patients may experience less morbidity. However, other reports have suggested that NACT in lieu of primary debulking is associated with an inferior overall survival. Direct comparisons have historically been difficult to perform.

In 1986, the GOG and a collaborative group in the Netherlands each opened randomized phase III trials to test the hypothesis that primary debulking was superior to NACT in advanced ovarian cancer. Both studies were closed because of poor accrual. One prevailing opinion at the time was that clinicians did not want to subject their patients to substandard NACT treatment. Until recently, the presumed benefits of primary surgical cytoreduction in advanced ovarian cancer had not been rigorously tested.

The results of a randomized phase III trial conducted in Europe were first presented in October 2008 and subsequently published in September 2010. The data caused a resumption of the debate about how best to initially treat women with advanced ovarian cancer. In the study, 670 patients were randomized to primary debulking surgery versus NACT. After 3 courses of platinum-based treatment, patients receiving NACT who showed a response underwent interval debulking. The investigators reported a median overall survival of 29 to 30 months, regardless of assigned treatment group. In the multivariate analysis, complete resection of all macroscopic disease at debulking surgery was identified as the strongest independent prognostic factor, but the timing of surgery did not seem to matter. Based on the investigators’ interpretation of their data, NACT and interval debulking was the preferred treatment.

Despite these findings, most gynecologic oncologists in the United States report that they use NACT for less than 10% of advanced ovarian cancers. Some European gynecologic oncologists have openly questioned what kind of evidence would be needed to convince their US colleagues about the superiority of the NACT approach. At least 2 criticisms of the trial have been suggested as reasons why the results may not be applicable in the United States. First, the duration of patient survival in the study was shorter than expected. The median survival (29–30 months) was less than half that reported for optimally debulked stage III patients receiving postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (66 months). In addition, only 42% of the primary debulking operations resulted in an optimal result with less than or equal to 1 cm of residual disease. Because expert centers in the US often report an optimal result in at least 75% of patients, it is feasible that a more aggressive initial attempt might have led to a better outcome for the group randomized to surgery. A prospective phase III trial conducted within the United States needs to be performed to sway opinion and change the practice of gynecologic oncologists in this country. Meantime, the controversy will persist and individual patterns of care will continue.

Secondary Debulking

Although the rationale for a second debulking operation at the time of relapse is an extrapolation of the rationale for primary surgery, there are several reasons why the certainty of clinical benefit is even more contentious. Recurrent ovarian cancer has a more heterogeneous disease presentation. As a result, treatment is typically more individualized. Secondary debulking is generally considered to be most effective when there is a single isolated relapse, a long disease-free interval after completion of primary therapy (ie, more than 12 months), when the patient is reasonably healthy, and when resection to minimal or no residual disease can be achieved. In contrast, women with symptomatic ascites, carcinomatosis, early relapse (ie, <6 months), and poor conditioning are least likely to benefit.

The clinical reality is that most patients are somewhere between these clinical extremes. Chi and colleagues proposed guidelines that are generally accepted ( Table 2 ), but, in practice, individual gynecologic oncologists use their own criteria for determining which, if any, patients are good candidates for secondary surgery. The previously reported retrospective series reflect this selection bias. Consequently, the success rates of optimal secondary debulking surgery and the corresponding survival data vary broadly. The potential for significant morbidity, and the notable lack of benefit for patients who are left with residual disease, emphasize the importance of careful counseling and preoperative assessment of patients. Predictably, complete resection seems to be associated with the most prolonged postoperative survival.