Despite being the most common gynecologic cancer in developed countries, there are many unanswered questions regarding optimal surgical management of endometrial cancer, including who should undergo surgical staging. There is evidence supporting the lower complication rate achieved with laparoscopic surgery compared with traditional open staging and building evidence to support laparoscopic-assisted robotic surgery for early endometrial cancer. Surgery plays an important role in the treatment of advanced stage disease, with retrospective studies showing some benefit to optimal cytoreduction. This review discusses the role of surgery in the management of endometrial cancer, with an emphasis on current controversies.

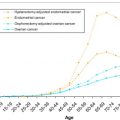

A total of 43,470 women were diagnosed with endometrial cancer in the United States in 2010, and 7950 died of the disease. Surgery plays a vital role in the management of endometrial cancer at all stages, particularly clinically early-stage disease. Despite being the most common gynecologic cancer in developed countries, there are still many unanswered questions regarding optimal surgical management of endometrial cancer, not the least of which is who should undergo surgical staging. There is ample evidence supporting the lower complication rate achieved with laparoscopic surgery compared with traditional open staging, and building evidence to support laparoscopic-assisted robotic surgery for early endometrial cancer. Surgery plays an important role in the treatment of advanced stage disease as well, with retrospective studies showing some benefit to optimal cytoreduction. This review discusses the role of surgery in the management of endometrial cancer, with an emphasis on current controversies.

Early-stage disease

Surgical Staging of Endometrial Cancer

Surgical staging is performed for prognosis and to direct adjuvant treatment. Endometrial cancer has been staged surgically since 1988. The procedure involves procurement of peritoneal washings (which no longer factor into the staging system but should be reported with the stage), hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and evaluation of the lymph nodes. Internationally, controversy continues as to what constitutes endometrial cancer staging, and even the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) staging booklet is vague. In the United States, the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) generally requires complete pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in protocols involving clinically early-stage endometrial cancer. Staging can be performed open, laparoscopically, or robotically. The incidence of lymph node metastases in patients with clinical stage I endometrial cancer ranges from 7.4% to 13.3%, with the incidence being significantly higher in patients with poorly differentiated and deeply invasive tumors.

The Role of Lymphadenectomy

Two large multicenter randomized control trials have been performed evaluating lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial cancer, and both concluded that lymphadenectomy did not change survival. The results have been interpreted in various ways, although most agree that these trials indicate that pelvic lymphadenectomy is not a therapeutic procedure.

ASTEC (A Study in the Treatment of Endometrial Cancer) was a multicenter trial in 4 countries involving 1408 women with clinically stage 1 endometrial cancer. Participants were randomized to hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) versus hysterectomy, BSO and pelvic lymphadenectomy, with a primary end point of overall survival. Patients with high-risk uterine factors were then further randomized to adjuvant therapy, regardless of lymph node status. After a median follow-up time of 3 years, there was no statistically significant difference in overall survival with lymphadenectomy (hazard ratio [HR] 1.16 in favor of no lymphadenectomy, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.81–1.54). Although there appeared to be a trend toward improved survival without lymphadenectomy, the lymphadenectomy group had more patients with aggressive histologies, as well as more patients who were found to have advanced disease (not including lymph node metastases) at the time of surgery.

Concurrently, in Italy, Panici and colleagues performed a similar multicenter trial involving 514 patients with clinical stage 1 endometrial cancer and evidence of myometrial invasion (at least 50% depth if grade 1) on frozen section. Hysterectomy with BSO and pelvic lymphadenectomy was compared with hysterectomy and BSO alone. The primary outcome was overall survival. The Italian trial differed from ASTEC in that adjuvant therapy was administered at the discretion of the treating physician, and the median lymph node count was 20 (as opposed to 12). After a median follow-up of 4 years, there was no statistically significant difference in overall survival with the addition of lymphadenectomy (HR for death 1.2, 95% CI 0.7–2.07), with 5-year overall survivals of 86% (lymphadenectomy) and 90% (no lymphadenectomy).

The ASTEC and the Italian trials show that there is not an independent survival advantage with pelvic lymphadenectomy. However, they do not fully answer the question of whether or not it is beneficial to perform lymphadenectomy because results of the lymphadenectomy were not used to direct treatment. In ASTEC, less than half of the patients who had positive lymph nodes were assigned to radiotherapy, and few patients in the trial received adjuvant chemotherapy or hormonal therapy. In the Italian trial, slightly more than 30% of each arm received adjuvant therapy, showing that lymphadenectomy had not been used specifically to make decisions on adjuvant therapy. These trials confirm the findings of PORTEC 1 (Post Operative Radiation Therapy in Endometrial Carcinoma), which showed that when patients are treated with adjuvant therapy regardless of nodal status, there is no survival benefit.

The complications reported in ASTEC and the Italian trial are listed in Table 1 , as are the complications from LAP-2, a GOG study comparing staging via laparotomy with laparoscopic staging for early endometrial cancer. Data from LAP-2 are included to report complications associated with laparoscopic staging, because more than 90% of patients in ASTEC and the Italian trial were staged via laparotomy. (The complications in LAP-2 are reported as intent to treat, meaning the 25.8% of patients who were converted to laparotomy are included in the laparoscopy arm.) Because of differences in reporting and patient populations, it is impossible to compare across studies, even in a hypothesis-generating manner. Overall, the incidence of serious complications was low, although higher with lymphadenectomy than without. Of particular interest is the incidence of lymphedema, which ranged from 3% to 13%. Lymphedema is bothersome to patients, and although it can be treated, it is not curable.

| Complication | ASTEC No LAD (n = 704) (%) | ASTEC LAD (n = 704) (%) | Italian No LAD (n = 250) (%) | Italian LAD (n = 264) (%) | LAP-2 Laparotomy a (n = 886) (%) | LAP-2 Laparoscopy b (n = 1630) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative | Not reported | Not reported | 1 | 1 | 8 | 10 |

| Vascular | Not reported | Not reported | <1 | <1 | 3 | 5 |

| Bowel | Not reported | Not reported | <1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Bladder/Ureter | Not reported | Not reported | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Other | Not reported | Not reported | <1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Postoperative | 2 | 6 | 14 | 30 | 21 | 14 |

| Ileus | 1 | 3 | Not reported | Not reported | 8 | 4 |

| Bowel obstruction | Not reported | Not reported | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | <1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Pulmonary embolism | Not reported | Not reported | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lymphocyst | <1 | 1 | Included in lymphedema | Included in lymphedema | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lymphedema c | <1 | 3 | 2 | 13 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Wound dehiscence | <1 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Reoperation | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 2 | 3 |

| Fistula | Not reported | Not reported | 0 | 1 | <1 | 1 |

| Late c | 12 | 17 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

a 99% of patients had at least pelvic lymph nodes removed.

b 98% of patients had at least pelvic lymph nodes removed.

Before prospective trials that documented the incidence of associated complications, lymphadenectomy had been considered a relatively benign procedure, particularly if it saved a patient adjuvant radiation. Now that multiple trials suggest that adjuvant radiation decreases local recurrence without improving overall survival, fewer patients receive adjuvant therapy even when unstaged. As seen in Table 1 , although complications are not frequent, the risks of serious complications associated with lymphadenectomy are notable. The question remains “Is the risk of lymphadenectomy more significant than the risk of missing a positive lymph node, which would prompt systemic therapy and possibly improve survival?”

It is a difficult question to answer: how do you weigh the impact of persistent side effects for a large group, versus the cost of 1 or more lives saved? It would require us to know the number of staging procedures that would need to be performed to discover 1 treatable lymph node metastasis, the improvement in median survival expected with systemic therapy for lymph node metastases, and the cost of the complications of staging to patients, in terms of quality-adjusted life-years. In the absence of those data, careful consideration must be given to the risks and benefits of lymphadenectomy to make the best treatment decisions for our patients. In the Italian trial, there were no surgery-related deaths ; in ASTEC, there was a 7% to 9% treatment-related death incidence in the lymphadenectomy group, although it is not clear what percentage was related to postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy. In LAP-2, the incidence of postoperative death within 30 days was 0.56% (laparoscopy) to 0.88% (laparotomy). There is no clear evidence-based threshold of risk for lymphatic metastases that should prompt lymphadenectomy; however, in light of the risk of major complications and treatment-related deaths, it seems reasonable to assume that the risk of lymph node metastases should be at least 3% to justify the risks associated with lymphadenectomy. This remains a controversial topic, with some investigators arguing for lower thresholds or systematic staging of all endometrial cancer cases.

Several systems have been proposed to identify patients at higher risk for lymph node metastases preoperatively or intraoperatively, all of which have similar limitations. Although it is agreed that grade, depth of invasion, and lymph vascular space invasion (LVSI) predict lymph node metastases and recurrence, it is difficult to come to consensus on criteria that reliably yield an incidence of lymph node metastases low enough to justify forgoing lymphadenectomy. In GOG 33, the surgical pathology study evaluating clinical stage 1 endometrial cancer, patients with either grade 1 tumors or endometrioid tumors with no myometrial invasion had an incidence of lymph node metastases less than 5%. However, there are several limitations: (1) the study required only a lymph node sampling (not a complete lymphadenectomy), (2) grade and depth from final pathology was used (which does not always concur with intraoperative evaluation), and (3) 2 key groups were underrepresented (grade 1 with deep one-third invasion and grade 3 with no myometrial invasion).

In 2000, surgeons at the Mayo Clinic proposed criteria for identifying patients with low-risk disease that are similar to those of GOG 33, with some modifications. The criteria are: type 1 (grade 1 or 2) endometrial cancer confined to the uterus and with 50% or less myometrial invasion and tumor diameter of 2 cm or less, or any grade with no myometrial invasion. The specification of tumor size resulted from work done by Schink and colleagues reporting a correlation between tumor size and incidence of lymph node metastases. In the original study from the Mayo Clinic, 9 of 187 women (5%) with grade 1 or 2 endometrioid tumors with less than 50% invasion on frozen section had lymph node metastases. Of 59 women who met the same criteria and had tumors 2 cm or less in diameter, 0% had lymph node metastases. Twenty-five percent of these same patients with LVSI had lymph node metastases as opposed to 3% of those without LVSI ( P <.0001). Significant limitations of this study included nonstandardized lymphadenectomy (many had lymph node sampling) and small sample size.

Other studies have found a low incidence of lymph node metastases with similar criteria. Examples include ASTEC, in which the incidence of metastases to the pelvic lymph nodes in patients with low-risk disease (grade 1 or 2 tumors with less than two-thirds myometrial invasion on final pathology) was 2%, and LAP-2, in which the incidence was 1% in 389 patients with grade 1 or 2 tumors less than 2 cm in diameter with less than 50% invasion. In contrast, a retrospective study of 834 women in Korea noted an incidence of 0.47% in women with grade 1 or 2 tumors with no myometrial invasion, but a higher than 3.5% incidence with any other tumors. This observation is most likely related to the fact that women were included in this study even if they had greater than clinical stage 1 disease on preoperative assessment. The major limitation of all of these studies (except that of Mayo Clinic) is that the correlation between risk factors and lymph node metastases is based on final pathology, whereas it is the frozen pathology report that is used to assess real-time risk of lymph node metastasis, thus the need for lymphadenectomy.

The most significant hurdle to adopting a system for identifying low-risk disease at the time of surgery is the reliability of frozen section. The Mayo Clinic has a sophisticated system for frozen diagnosis, including specialized equipment not universally available. A retrospective study of 24,880 frozen sections performed during 1 year at the Mayo Clinic on all tissue types revealed an accuracy of 97.8%. A recent presentation at the 2011 Annual Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists from the Mayo Clinic compared frozen section with final pathology in 809 women having surgery for endometrial cancer. In only 1.4% of patients, final pathology differed from frozen section such that it would have altered surgical management (based on the Mayo criteria). Several studies have looked at the accuracy of intraoperative evaluation of depth (gross or frozen) and grade. Reliability varies from institution to institution. In 1 study the accuracy of depth by gross inspection was 87.3% for grade 1 lesions, with underestimation 5% of the time. However, with increasing grade the ability to accurately predict depth of invasion decreased, with the depth of invasion underestimated more than 50% of the time in grade 3 tumors.

Convery and colleagues recently performed a retrospective study using data from the University of Virginia and Duke University that validated the Mayo criteria. All patients who had intraoperative frozen pathologic consultation and met Mayo criteria were included in this analysis. Among 110 women meeting criteria who had lymphadenectomy (at least 8 lymph nodes removed), the incidence of lymphatic metastases was 1.8%, which carries a 98.2% negative predictive value. Women with tumors greater than 2 cm who otherwise met the Mayo criteria and had a lymphadenectomy performed were also evaluated (a total of 140 women) and found to have a 2.9% incidence of lymph node metastases. Although this is only 1 study, it lends support to the value of intraoperative pathologic consultation to guide surgical decision making.

Omitting lymphadenectomy in grade 1 or 2 tumors with less than 50% invasion, no LVSI, and a diameter of 2 cm or less on final pathology likely yields an acceptable incidence of undiagnosed lymph node metastases. The predictive value of the Mayo criteria has been reproduced in 1 study and may be an appropriate standard depending on the institution. Gynecologic oncologists need to communicate with their pathologists and perform internal quality assurance to determine what thresholds to use intraoperatively to reliably meet these goals on final pathology at their own institution. When attempting to ascertain depth of myometrial invasion intraoperatively, using a lower threshold may help to avoid underestimation.

Extent of Lymphadenectomy

Both of the randomized controlled trials evaluating lymphadenectomy mentioned earlier required only pelvic lymphadenectomy. There has been much discussion about whether or not pelvic lymphadenectomy is appropriate. Metastases to the para-aortic lymph nodes portend worse survival than pelvic lymph node metastases alone, which is reflected in the new FIGO staging system. Many believe that to evaluate the true therapeutic value of lymphadenectomy, a complete lymphadenectomy, including the para-aortics, should have been performed in the randomized controlled trials. To substantiate this theory, these investigators reference a study from the Mayo Clinic that reported that among 281 women who underwent staging for apparent clinical stage 1 disease, 57 had lymph node involvement, 38 of whom had para-aortic lymph node metastases. To those who believe lymphadenectomy has therapeutic value, that finding means that patients who did not have para-aortic lymphadenectomy could have had disease left behind. In the same study, the incidence of isolated para-aortic lymph node metastases was 2.6% in women with type 1 disease and 4.1% in women with type 2 disease (3.2% overall). Whether one believes para-aortic lymphadenectomy is therapeutic or prognostic, patients with metastases to the para-aortics are the most likely to benefit from systemic therapy. Para-aortic lymphadenectomy is considered by many to be an important component of a complete lymphadenectomy, dictating prognosis and directing treatment.

The debate still remains regarding what the appropriate surgical plan should include if high-risk uterine factors are identified on frozen section analysis, but para-aortic lymph nodes cannot be removed safely. If pelvic lymph nodes are accessible, should they be removed in this situation? Some surgeons believe that after peritoneal washings, hysterectomy, and BSO, no further staging is warranted and decisions should be made on uterine factors. Others believe pelvic lymphadenectomy is better than no evaluation of the lymph nodes. In most cases (pending results of ongoing GOG trials regarding adjuvant chemotherapy), the therapy prescribed based on uterine factors in type 1 disease includes radiation therapy, which does not include the para-aortic region. If the para-aortics are not safely accessible, it is best to perform the pelvic lymphadenectomy and use the pathologic results to guide decisions on adjuvant therapy, especially given that the incidence of isolated para-aortic lymph nodes metastases is only 2% to 2.6% in type 1 disease.

There are proponents of extending the lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer above the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) based on the lymphatic drainage pathway from the fundus toward the renal vessels. In recent GOG protocols, the IMA is the upper border of the lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer. With the value of lymphadenectomy already in question, the increased complication rate associated with extending the dissection above the IMA, with the intent of identifying isolated high para-aortic lymph node metastasis, may outweigh the benefit.

Nonendometrioid Histologies

In patients with clear cell or uterine papillary serous adenocarcinoma, the risk of distant metastases is significantly increased. Whenever possible, patients with these histologies should undergo full surgical staging, not only for prognosis and therapeutic decision making but also for the opportunity to be enrolled in clinical trials. Given the higher incidence of occult metastases, staging usually includes an omental biopsy in addition to the usual staging procedures.

Minimally Invasive Surgical Staging: Laparoscopic and Robotic

The concept of laparoscopic staging of endometrial cancer was introduced in the early 1990s ; however, staging via minimally invasive techniques has only recently become widely accepted as a fully acceptable therapeutic option. This transition to minimally invasive surgical staging correlates with the approval of the Da Vinci robot for use in gynecologic surgery in 2005 by the US Food and Drug Administration and the adoption of robotic surgery by a few key forward-thinking gynecologic oncologists who popularized the approach. Multiple retrospective studies and 3 randomized trials have shown the safety and feasibility of the laparoscopic and robotic surgical approaches.

The GOG conducted LAP-2, the largest randomized trial evaluating laparoscopic versus open staging of endometrial cancer. Initially, LAP-2 was intended to evaluate feasibility and complications associated with the 2 techniques; midtrial the primary end point was changed to median time to recurrence and the sample size was adjusted. There were 1682 women in the laparoscopy arm and 920 in the laparotomy arm. The incidence of conversion to open surgery was 25.8%, with that risk closely correlated with body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters). Patients undergoing laparoscopy had significantly longer operating time (204 vs 167 minutes, P = .001) and shorter hospital stay. There was a slightly higher (but not significant) risk of intraoperative complications with laparoscopy as opposed to laparotomy (10% vs 8%, P = .106, see Table 1 for details). Perioperative mortality was similar in the 2 groups (0.59% vs 0.88%, P = .404) and mostly attributable to pulmonary embolism. Postoperative complications were significantly increased in the laparotomy group (14% vs 21%, P <.001). A study using FACT-G (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy: General) and other validated scales in a subset of LAP-2 patients reported a small benefit in quality of life (QoL) in the first 6 weeks after surgery for patients randomized to laparoscopy, although by 6 months postoperatively, QoL was equivalent regardless of surgical approach.

Most patients in LAP-2 successfully underwent pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy; however, a higher percentage of patients were staged in the laparotomy group versus the laparoscopy group (96% vs 92%, P <.001). Data on risk of recurrence have not been published, but were preliminarily presented as a late-breaking abstract at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology by Dr Joan Walker. There is no difference in risk of recurrence and survival at 3 years between patients randomized to laparoscopy versus laparotomy. Provided the final results continue to show no difference in oncologic outcome, minimally invasive surgery should be considered the preferable treatment of endometrial cancer in light of the lower rate of complications and faster recovery. As experience with minimally invasive staging increases, the risk of conversion decreases, which may result in an even lower incidence of postoperative complications. The risk of conversion in the 2 smaller randomized control trials of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for endometrial cancer staging ranged from 0% to 3.8%.

Robotic-assisted laparoscopic endometrial cancer staging has been evaluated retrospectively, mostly using historical laparoscopic and laparotomy controls. Although limited by selection bias, such studies are helpful in showing the overall safety and feasibility of the robotic approach. Recurrence and survival data are not evaluated, although if the robot is thought of as a surgical tool that assists in laparoscopy rather than a unique surgical procedure, such evaluation is probably not necessary. In most studies, the risk of conversion to laparotomy was lower with robotic-assisted surgery than laparoscopic staging, even although the median BMI of patients staged robotically was often higher than those staged laparoscopically.

Determining Surgical Approach

Assessing a patient for a minimally invasive surgical approach requires consideration of 3 categories: patient characteristics, uterine factors, and surgeon experience. Patients who are normal to slightly overweight, with few comorbidities and little to no previous surgery can be staged in any fashion, although data support making every effort to offer those patients a minimally invasive approach.

Obesity and Minimally Invasive Surgery

Obesity is a known risk factor for type 1 endometrial cancer, thus consideration must frequently be given to the best surgical approach for overweight and severely obese patients. Obese patients are more likely to have diabetes and poor nutritional status, placing them at higher risk for multiple postoperative complications, including wound infections. It can be assumed that avoiding a large laparotomy incision is in the patient’s best interest.

In LAP-2, the incidence of conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy correlated with BMI, with a sharp increase when the BMI was greater than 35. That is not surprising: at a certain point, the thickness of the anterior abdominal wall severely limits range of motion. Also, because the fulcrum of the straight stick laparoscopic instrument is wider than in a thinner patient, small, subtle movements are more challenging. Much like driving without power steering, the surgeon must make large, exaggerated movements outside the patient’s body to move the instruments intraperitoneally, which decreases precision. Robotic surgery has answered these challenges somewhat with articulating instruments, which allow for range of motion intraperitoneally with minimal movement outside the patient. In addition, the weight of the abdominal wall is borne by the robotic arms, not the surgeon, who is subject to fatigue.

Although robotic surgery is often seen as preferable for very overweight and obese patients with endometrial cancer, it is not feasible in all cases. BMI is a valuable tool to guide a surgeon; however, it does not account for other factors that can ultimately lead to conversion to laparotomy. Exposure for lymphadenectomy is obtained by reflecting the small bowel into the upper abdomen. Short mesenteric length can severely limit the ability to stage robotically or laparoscopically because it makes exposure of the aortic bifurcation extremely difficult; this is compounded in obese patients with a thick mesentery and heavy epiploica. Even more important than the amount of adipose is the distribution: centripetal obesity is the most challenging because of mesenteric fat impeding exposure and adipose-laden lymphatic beds that can make blood vessels, nerves, and the ureter more difficult to identify and protect. Patients should be examined sitting and lying down because if the patient’s weight falls laterally when she is supine, they may be a better candidate than a smaller patient whose weight remains centrally positioned. It is particularly difficult to perform robotic lymphadenectomy in patients who are short-waisted because there is minimal space in which to retract bowel, which limits visualization.

Despite the objective and subjective data, the decision regarding the best surgical approach is determined by the surgeon, taking multiple factors into consideration. Given that in LAP-2 the conversion rate was 26% and the postoperative complication rate was still significantly lower in the patients assigned to laparoscopy, it is reasonable to attempt a minimally invasive surgical approach in patients who may be borderline in terms of feasibility, recognizing that conversion is more likely. With more and more fellowship graduates being trained robotically, the new generation of gynecologic oncologists may eventually be more comfortable robotically than open, meaning that a patient who may not be a candidate for a robotic lymphadenectomy is not a candidate for lymphadenectomy at all.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree