Fig. 11.1

Schema for initial evaluation and categorization of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma

11.1.4 Stratification Using MDACC Borderline Patient Types

In practice, the fitness of each patient for pancreatic surgery is evaluated first (Fig. 11.1). A patient who is too frail for surgery secondary to uncorrectable comorbidities does not need to undergo extensive evaluation for surgical resection or consideration for preoperative therapy since surgical resection will not be the end result. These patients can therefore be efficiently triaged for palliative therapy or supportive care. If the patient is not currently fit for surgery but has a potentially reversible condition, then medical optimization or pre-habilitation during preoperative therapy is the goal. These patients are referred to as BR-C and are generally older (median age 75 years) with a higher ECOG status (44% ECOG 2) usually secondary to cardiopulmonary disease (63%). If the patient is fit for surgery, biological staging is the next. Evidence of distant metastases on radiographic imaging is a contraindication to resection, but in many cases there are suspicious radiographic findings, but not diagnostic for distant metastatic disease. These patients are termed BR-B and receive chemotherapy followed by restaging. Similarly, patients with a high CA-19-9 (≥1,000) even with negative imaging are considered BR-B and receive chemotherapy followed by restaging. Finally, local anatomic factors related to the primary tumor are considered in patients who are without metastases and are fit for surgery. This necessitates careful review of radiographic image using standard anatomic criteria designed to categorize tumors as resectable, borderline, or locally advanced. Patients who are fit for surgery with no evidence or suspicion of metastases and borderline tumors are considered BR-A and usually receive chemotherapy plus or minus chemoradiation and restaging prior to proceeding with surgical resection.

11.1.5 Clinical Application of MDACC Borderline Patient Types

Clinical application of this approach to initial evaluation identifies that at least 50% of our patients have borderline clinical features. When treated preoperatively, only 37% of BR-C patients can be expected to undergo resection, while the others fail to reach surgical resection due to poor performance status (31%) or interval identification of metastatic disease (26%). BR-C patients who receive resection experienced a median survival of 38.6 months versus 13.3 months (p = 0.02) for those not receiving surgery. Roughly 46% of BR-B patients receive surgical resection of preoperative therapy, and an equal portion (46%) is found to have distant metastases precluding surgery. The loss of performance status is uncommon (4.9%) in BR-B patients. Resection conferred a 33-month median survival versus 11.8 months in those patients unable to proceed to resection (p < 0.001). Of note, local progression was rarely observed during preoperative therapy in either BR-B or BR-C patients (2.6%) [15, 17]. Management of patients with BR type A is considered below.

Key Point

Pretreatment evaluation of patients can aid in accurate communication and treatment planning for patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer; many patients may have technically resectable tumors but may not be adequate candidates for surgery.

11.2 Defining Borderline Resectable PDAC Tumors

11.2.1 Imaging Using Contrast-Enhanced CT

All patients with apparent localized disease are evaluated with a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan, which provides essential information about presence of regional or distant metastases and the site and local extent of the primary tumor. This allows the surgeon to determine whether the patient has a resectable tumor and the likelihood of a margin negative resection. Multi-detector row CT is the most widely used staging modality for pancreas cancer and a workhorse for new patient evaluation. When performed and interpreted correctly, it provides valuable staging for both distant and regional metastases as well as local extrapancreatic extension of the primary tumor to adjacent critical vascular structures [18]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends that all patients with suspicion for PDAC have a dedicated pancreas protocol CT scan as part of the initial evaluation (Version 2.2015). At MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), a pancreas protocol CT scan uses water as a negative oral contrast agent and starts with pre-contrast imaging from the dome of the liver extending caudally to include the entire liver reconstructed to 2.5 mm slice thickness. Next, 125 ml of iodinated contrast is administered intravenously at a rate of 3–5 ml/s. The pancreas phase/arterial phase uses bolus tracking, and images are obtained 10 s after a Hounsfield unit value of 100 is reached in the aorta at the level at the celiac axis from the dome of the liver to the iliac crests. Images for the portal venous phase are obtained at a 20 s delay from the pancreas phase. Hepatic metastases are usually best visualized on the portal venous phase. Delayed images are obtained 15 s after the portal venous phase. The images are reconstructed to 2.5 mm slice thickness for imaging review and at 0.625 mm or 1.25 mm slice thickness to create coronal and sagittal reformatted images [19].

11.2.2 CT Identification of Pertinent Vascular Anatomy

The primary pancreatic tumor is best seen on the pancreas phase of the CT scan and is usually a hypodense mass, because the surrounding normal pancreatic parenchyma enhances. The pancreas phase/arterial phase illuminates the branches of the celiac axis and superior mesenteric artery (SMA), enabling one to identify important arterial anatomy variants and discern whether the tumor has any arterial involvement. As many as 40–45% of patients have variants of “normal” hepatic arterial anatomy, which are of vital importance to appreciate on preoperative imaging as these variants can impact operative planning [20]. A replaced or accessory right hepatic artery is present in up to 15% of patients and most commonly arises from the SMA and courses posterior to the pancreas and posterolateral to the bile duct. An additional 2.5% of patients have a replaced common hepatic artery (CHA) that arises from the SMA and follows a similar path to a replaced or accessory right hepatic artery. The superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and portal vein (PV) are best evaluated on the portal venous phase. The initial staging CT scan has 94% sensitivity and 84% specificity of determining vascular involvement, and the surgeon should carefully note the tumor-vein interface, vein contour, and/or deformity; there are multiple classification schemes that predict venous involvement based on imaging characteristics, and these should be employed for operative planning [21–24]. Additionally, the surgeon should identify the location and relationship of the gastroepiploic vein, colic veins, inferior mesenteric vein (IMV), and jejunal/ileal branches of the superior mesenteric vein as these have variable courses, and the drainage pattern directly impacts surgical options for reconstruction of the superior mesenteric-portal vein (SMV-PV) confluence, which can be expected in over 40% of cases. Terminology that describes vascular involvement has become standardized and is reviewed in detail below. If the vascular involvement is ≤180°, the circumference of the vessel is termed abutment. If the vascular involvement is >180°, the circumference of the vessel is termed encasement. The importance of properly staging patients and determining potential vascular involvement is a cornerstone of treatment planning and cannot be overstated [25].

11.2.3 Imaging Definitions of Resectability

As patient assessment, imaging, and multidisciplinary treatment techniques for patients with localized PDAC were refined in the late 1990s, it became evident that this patient group included a spectrum of primary tumor types from removable to unresectable. To allow common classification, the multidisciplinary team at MDACC developed imaging criteria that are still in use that define clinically resectable (CR) tumors by the following: (1) absence of extrapancreatic disease; (2) clear tissue plan between the tumor, the celiac axis, hepatic artery, and SMA; and (3) a patent SMV-PV confluence, abutment, or encasement is allowed as long as the vessel is patent [4, 16, 26]. Locally advanced (LA) tumors are defined by the following: (1) encasement of the celiac axis, (2) encasement of the hepatic artery with no options for vascular reconstruction, (3) encasement of the SMA >180°, and (4) occlusion of the SMV-PV confluence with no options for vascular reconstruction [4, 16, 26]. Patients who were classified as CR based on these imaging criteria were likely candidates for a R0 resection, while patients with LA tumors were unlikely to respond to chemotherapy and/or chemoradiation to a degree that would allow surgical resection; however, improved response to systemic therapy increasingly allowed patients with advanced tumors to undergo resection.

Currently, NCCN defines resectable PDAC as a tumor with no contact of celiac axis, SMA, or CHA and no contact with the SMV-PV or ≤180° contact without vein contour irregularity (Version 2.2015). LA PDAC of the head/uncinate process is a tumor that contacts the SMA >180°, the celiac axis >180°, the first jejunal SMA branch, and the most proximal draining jejunal vein or has unreconstructible SMV-PV involvement or occlusion. Tumors of the body/tail are LA when there is contact of >180° with SMA or celiac axis, contact with the aorta, or unreconstructible SMV-PV involvement or occlusion (Version 2.2015).

11.2.4 Imaging Criteria for Borderline Resectable Tumors

In 2001, Mehta et al. described a group of “marginally” resectable patients who were treated with chemoradiation preoperatively in order to downstage the tumor and increase the likelihood of a margin negative resection [27]. “Marginally” resectable was defined as a tumor in which the perivascular fat plane was absent over 180° of the SMA, SMV, or PV and persisted for a length >1 cm [27]. The NCCN adopted the term “borderline resectable” in 2006 to describe patients with localized tumors who blurred the lines between CR and LA tumors. These patients were felt to be at higher risk of a margin-positive resection, if upfront surgery was employed; thus, the NCCN suggested the use of preoperative therapy.

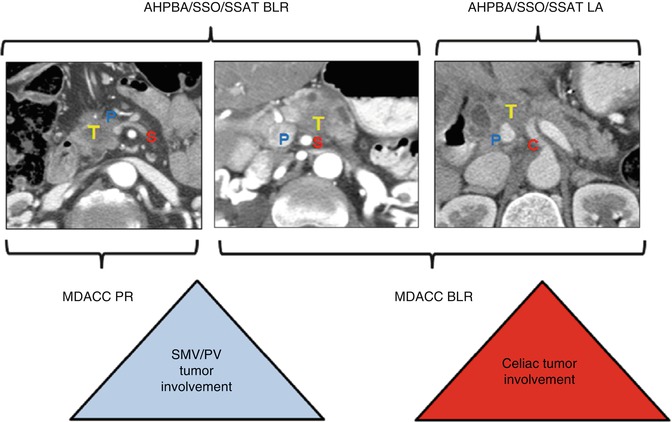

Over the last several years, several groups developed specific radiographic features to define BR-PDAC. At MDACC, the imaging criteria used to define a BR tumor are (1) abutment of the celiac axis, (2) abutment of the hepatic artery or short-segment encasement, (3) abutment of the SMA ≤180°, and (4) short-segment occlusion of the SMV-PV confluence amendable to resection and reconstruction [4, 16, 26]. The AHPBA, SSO, and SSAT societies define BR-PDAC as tumors with no abutment or encasement of the celiac axis, short-segment abutment or encasement of the CHA amenable to reconstruction, abutment <180° of the SMA, or abutment with or without impingement or narrowing of the SMV-PV or encasement with or without occlusion with suitable vein proximal and distal to allow resection and reconstruction [28, 29]. The difference between the MDACC and AHPBA/SSO/SSAT definitions hinges around the extent of SMV-PV involvement that differentiates BR from resectable tumors (Fig. 11.2). The NCCN definition for BR-PDAC has changed multiple times over the years but currently includes tumors of the head/uncinate process that contact the CHA without extension to the celiac axis or the hepatic artery bifurcation, contact ≤180° of the SMA, contact >180° of the SMV or PV, contact ≤180° with a contour irregularity or thrombosis of the SMV-PV with suitable vessel proximal and distal that will allow venous resection and reconstruction, or contact with IVC. Tumors of the body/tail are classified as BR when there is contact of ≤180° with the celiac axis or contact of >180° with the celiac axis without involvement of the aorta and an intact and uninvolved gastroduodenal artery (Version 2.2015) (Table 11.1 ).

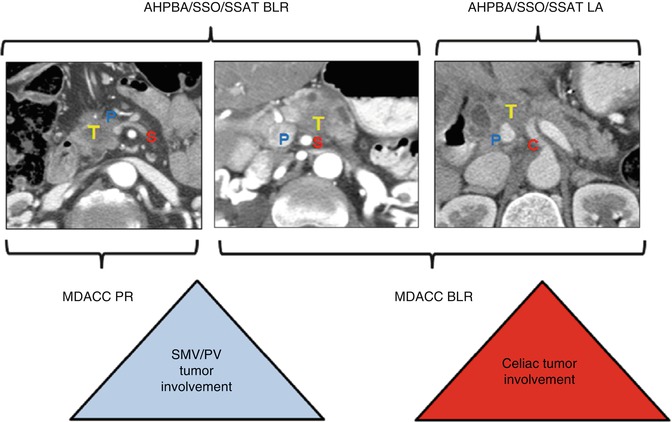

Fig. 11.2

This schematic uses representative CT scan images to display the overlap between definitions of borderline resectability between MDACC and AHPBA/SSO/SSAT criteria. MDACC criteria allow SMV-PV involvement (P) of the tumor (T) within the potentially resectable group but allow tumor abutment of the celiac trunk (C) within the borderline group

Table 11.1

Definitions of BR-PDAC

MDACC | AHPBA/SSO/SSAT | NCCN | |

|---|---|---|---|

CA | Abutment | No abutment or encasement | Contact ≤180° |

CHA | Abutment of short-segment encasement | Short-segment abutment or encasement amenable to reconstruction | Contact without extension to celiac axis or hepatic artery bifurcation amenable to resection and reconstruction |

SMA | Abutment <180° | Abutment <180° | Contact ≤180° |

SMV-PV | Short-segment occlusion amenable to resection and reconstruction | Abutment >180° or occlusion amenable to resection and reconstruction | Contact of >180°, contact of ≤180° with irregularity of vein or thrombosis amenable to resection and reconstruction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|