Abstract

Objectives

Microwave ablation (MWA) has gained attention as a minimally invasive and safe alternative to surgical intervention for patients with small renal masses; however, its cost-effectiveness in Australia remains unclear. This study conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis to evaluate the relative clinical and economic merits of MWA compared to robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy (RA-PN) in the treatment of small renal masses.

Methods

A Markov state-transition model was constructed to simulate the progression of Australian patients with small renal masses treated with MWA versus RA-PN over a 10-year horizon. Transition probabilities and utility data were sourced from comprehensive literature reviews, and cost data were estimated from the Australian health system perspective. Life-years, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), and lifetime costs were estimated. Modelled uncertainty was assessed using both deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses. A willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of $50,000 per QALY was adopted. All costs are expressed in 2022 Australian dollars and discounted at 3% annually. To assess the broader applicability of our findings, a validated cost-adaptation method was employed to extend the analysis to 8 other high-income countries.

Results

Both the base case and cost-adaptation analyses revealed that MWA dominated RA-PN, producing both lower costs and greater effectiveness over 10 years. The cost-effectiveness outcome was robust across all model parameters. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses confirmed that MWA was dominant in 98.3% of simulations at the designated WTP threshold, underscoring the reliability of the model under varying assumptions.

Conclusion

For patients with small renal masses in Australia and comparable healthcare settings, MWA is the preferred strategy to maximize health benefits per dollar, making it a highly cost-effective alternative to RA-PN.

1

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for more than 90% of kidney cancers, which are estimated to result in 1.8% of all deaths from cancer in 2022 in Australia [ , ]. The widespread use of routine imaging has contributed to a substantial increase in the detection of small renal masses [ ], making it possible to treat kidney cancer in the early stages. This shift has paved the way for nephron-sparing approaches, such as partial nephrectomy and ablative therapies, to become more common in clinical practice [ , ].

Although partial nephrectomy is the mainstay option in the treatment of incidental small renal masses [ , ], ablation may confer key advantages over surgery as a less invasive and potentially less costly alternative [ , ]. Image-guided minimally invasive ablative therapies such as radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, and cryoablation, have become more common over the last decade in treatment of small tumors, and are currently recommended by several international urological associations ( Supplementary Table 1 ) [ ]. In recent years, the feasibility of percutaneous microwave ablation (MWA), for small RCC has been well-established [ , ]; however, there is currently no specific clinical guideline to recommend the use of ablation in small renal masses in Australia.

In clinical practice, once a small renal mass is identified as potentially malignant, the decision to treat is often driven by the goal of achieving curative outcomes. Our study specifically focuses on comparing ablation and partial nephrectomy, as these are the most relevant treatment options for patients with RCC or presumed RCC who are candidates for active intervention. Active surveillance, while a valid option for some patients, is generally not preferred for confirmed or presumed RCCs in individuals who are fit for surgery or ablation.

There is a lack of evidence on the cost-effectiveness of MWA compared with surgical resection for the treatment of small renal masses, with no Australian studies to date. Two life table-based models have compared the cost-effectiveness of MWA versus surgical procedures in treating small renal masses in the US setting, with mixed results ( Supplementary Table 2 ) [ , ]. Cost effectiveness analysis in variety of countries for management options for SRMs was recommended by a recent systematic review [ ]. The objective of this study was to evaluate the cost effectiveness of percutaneous MWA compared to robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RA-PN) for the treatment of small renal masses from the perspective of the Australian public health care system.

2

Materials and methods

We have adhered to a predefined economic evaluation plan and report our findings using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards [ ]. This study received an ethics exemption from the Metro North Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: EX/2021/QRBW/81357) due to the quality assurance nature of the project [ ]. No industry support was provided for this study and the study authors had control of the data and information submitted for publication.

2.1

Model design

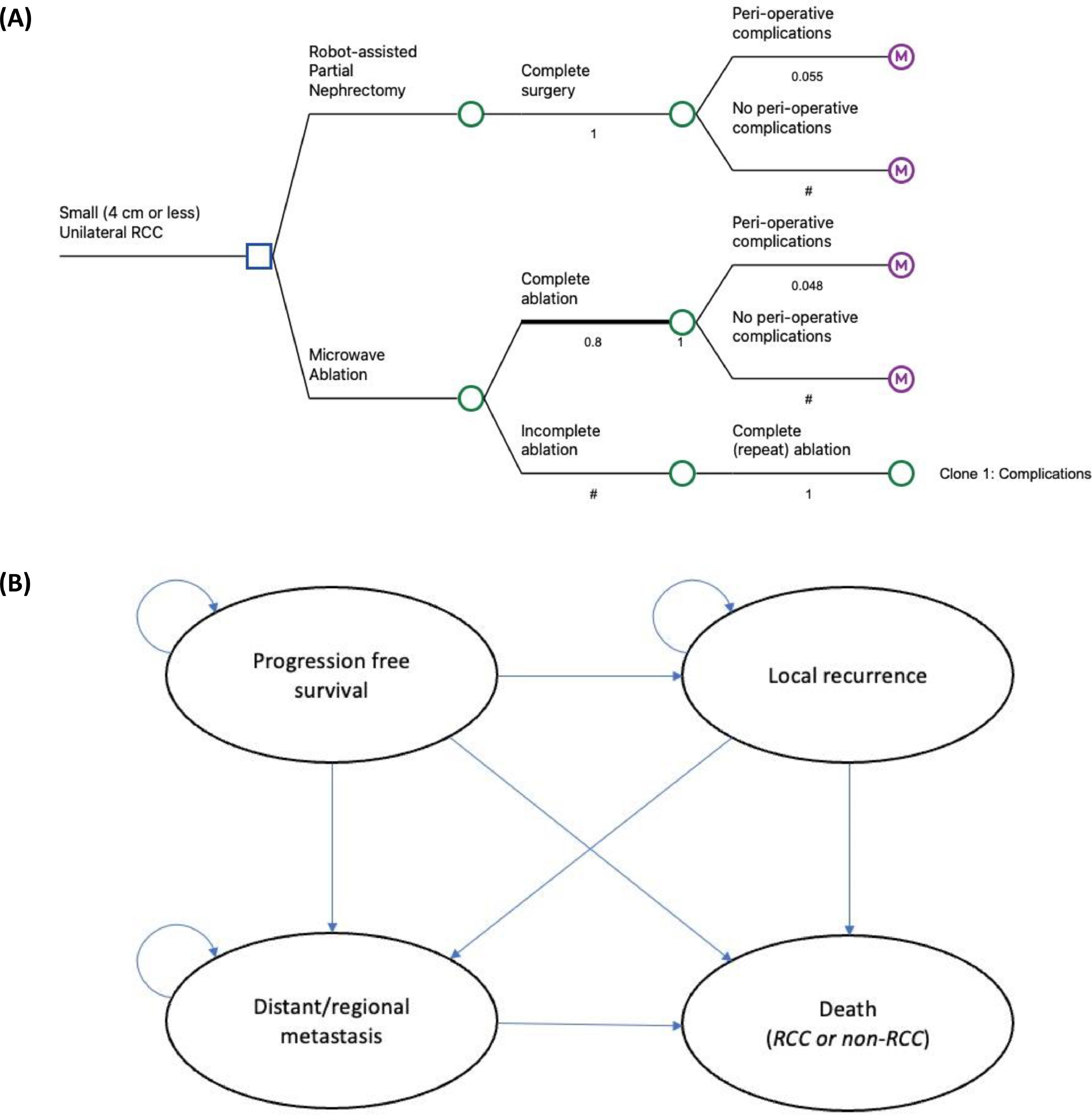

We developed a half-cycle corrected state-transition Markov model using TreeAge Pro Suite 2022 (TreeAge Software, Cambridge, Massachusetts) [ ] to estimate the direct health system costs and quality adjusted life years (QALYs) of MWA versus RA-PN for patients with unilateral early stage RCCs with tumor size ≤4 cm. The model adopted an Australian healthcare system perspective over a 10-year horizon with a 3% annual discount rate applied for both cost and health outcomes. A discount rate is applied in health economic models with long-term horizons to reflect the present value of future outcomes [ ], and a 3% was selected based on the latest evidence with 1.5% and 5% considered in sensitivity analyses [ , ]. The model structure ( Fig. 1 ) was based on a previously published model [ ] and tailored to fit the Australian setting based on clinical opinions from 3 interventional oncologists.

The analysis was based on a 2-part constructed model, decision tree ( Fig. 1 A) and Markov model ( Fig. 1 B ), designed to represent the 30-day after undergoing the intervention and the long-term periods of time. A decision tree was used to allocate patients to an initial management strategy, with MWA as the intervention arm and RA-PN as the comparator. We assumed that all tumors were completely removed after partial nephrectomy, whereas 80% of tumors were completely ablated after 1 MWA procedure, and the remaining 20% were ablated after undergoing a second procedure [ ]. The model included the probability of major complication rates, and associated costs, for each arm [ , , ]. Minor complications were excluded due to their tendency to self-resolve and unlikely associated management costs. Peri-operative death wasn’t considered since both procedures reportedly have similar, negligible mortality rates.

After the short-term decision tree model, patients would enter a 4-state Markov state transition model with a 12-month cycle length. All patients initially entered a “progression free survival” health state, with the potential to remain in this state at the end of each cycle or to experience a local recurrence, distant metastases, or death due to RCC or non-RCC reason. Patients with local recurrence were at risk of developing distant metastases or death, while those with metastatic RCC were subject to risk of death. Relevant treatment and follow-up therapies were assumed to be provided to patients once local recurrence or distant metastasis occurred. Supplementary Fig. 1 depicts the treatment pathway for patients after MWA or RA-PN in the Australian setting.

2.2

Model inputs and data sources

The data selection process followed the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Research Modelling Good Research Practices guidelines [ , ]. All input parameters are detailed in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3 along with the plausible range of uncertainty tested within 1-way sensitivity analyses. Supplementary Table 4 outlines data inputs with respective statistical distributions as applied in the probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

| Parameter and source | Base-case estimate | Univariate sensitivity analysis range | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition probability | |||

| Major Peri-operative complication rate for ablation | 0.048 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | Lucignani (2024) [ ] McClure (2023) [ ] Cazalas (2021) [ ] |

| Major Peri-operative complication rate for partial nephrectomy | 0.055 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | Lucignani (2024) [ ] McClure (2023) [ ] Cazalas (2021) [ ] |

| Annual probability of local RCC recurrence after ablation a | 0.0038 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | Chlorogiannis (2024) [ ] |

| Annual probability of local RCC recurrence after partial nephrectomy a | 0.0065 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | Chlorogiannis (2024) [ ] |

| Annual probability of developing metastatic RCC after ablation a | 0.0038 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | Chlorogiannis (2024) [ ] |

| Annual probability of developing metastatic RCC after partial nephrectomy a | 0.0065 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | Chlorogiannis (2024) [ ] |

| Annual probability of developing metastatic RCC after local RCC recurrence | 0.129 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | Herout (2018) [ ] |

| Annual mortality rate after local RCC recurrence | 0.0615 | 0.0549–0.0691 | SEER explorer [ ]; Shi (2020) 35 |

| Annual mortality rate after metastatic RCC | 0.3194 | 0.3009–0.3382 | SEER explorer [ ]; Shi (2020) 35 |

| Annual mortality rate for progression-free survivors b | 0.0123 | 0.0122–0.0131 | 2020-2022 Australian Life Table [ ] |

| Resource use and costs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term direct cost of ablation (including length of stay) | $6,763 | $6,255–$7,245 | Hospital costing data [ ] |

| Short-term direct cost of partial nephrectomy (Robotic assisted nephrectomy) (including length of stay) | $21,302 | $19,172–$23,432 | Hospital costing data [ ] |

| Cost of managing major peri-operative complications after ablation c | $8,270 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | AR-DRG codes: L03A, L03B, L03C |

| Cost of managing major peri-operative complications after partial nephrectomy c | $29,404 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | |

| Annual management cost for progression-free survivors (including follow-up CT scans, interventional Radiologist and urologist appointments) after ablation or partial nephrectomy d | $1373 for the first year, and then $773.35 annually for 4 years | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | MBS[ ] and Expert opinion |

| Oncology CT scan (unit cost) | $424.60 | – | Item 56553 |

| Interventional radiologist or urologist appointment (unit cost) | $62.75 to $284.20 | – | Items 2801 to 3093 |

| Cost of immunotherapy for metastatic RCC e | $278,114.4 for 21 months | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | PBS and Expert opinion |

| ipilimumab (unit cost) | $16,964.83 | – | Item 11628B |

| nivolumab (unit cost) | $9,557.05 | – | Item 10745M |

| Annual management cost of metastatic RCC (including administration, blood test, and CT scans) f | $13,859.3 | (0.8–1.2) × BCE | MBS[ ] and Expert opinion |

| Immunotherapy administration cost (unit cost) | $62.75 to $284.20 | – | Items 2801 to 3093 |

| Blood test (unit cost) | $25.55 | – | Items 65060, 65090, 65096 |

| Oncology CT scan (unit cost) | $424.60 | – | Item 56553 |

| Health state utility | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient utility since the second month g | 0.89 for males in age group of 65-74 years | 0.8773–0.9027 | 2024 Australian Population Norms [ ] |

| Utility for patient live with recurrence | 0.705 | 0.64–0.77 | McAlpine (2021)[ ] Wu (2023)[ ] Su (2022)[ ] |

| Utility for patient live with metastasis | 0.415 | 0.30–0.53 | McAlpine (2021)[ ] Wu (2023)[ ] Su (2022)[ ] |

| Additional inputs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Discount rate | 0.03 | 0.015–0.05 | |

| Time horizon h | 10 | 2–20 (lifetime length) |

a The transition probabilities were calculated based on the local recurrence-free survival rate and metastasis-free survival rate: 97% and 95% for MWA and 97% and 95% for RA-PN, which were extracted from a propensity-matched cohort study focusing upon long-term follow-up of oncologic outcomes of percutaneous MWA ( n = 59) and RA-PN ( n = 59) for the treatment of T1a RCCC by Chlorogiannis (2024) [ ].

b The background mortality rate was estimated from the life expectancies reported in 2020-2022 Australian Life Table [ ]. Life expectancy at birth was 81.2 years for males (base-case estimate), with the highest in the Australian Capital Territory for males (82.2 years) (the upper interval) and the lowest in the Northern Territory for males (76.2 years) (the lower interval) in 2020–2022.

c The costs associated with managing peri-operative complications were derived from AR-DRG codes specific to kidney interventions. These codes include L03A (representing the cost for PN with major peri-operative complications), L03B (indicating the cost for ablation with major peri-operative complications), and L03C (denoting the cost for either PN or ablation without any peri-operative complications). For ablation-related complications, the estimated management cost stands at $8,270, calculated by subtracting the cost under L03C from that of L03B. Similarly, the management cost for complications post-PN is approximated at $29,404, determined by deducting the L03C cost from the L03A cost. In the model, we incorporated the costs of peri-operative complications, adjusted according to the observed rate of these complications.

d In follow-up, CT scan at 3 months then annual CT scans for 5 years; 1 Interventional radiologist appointment within the first year; and 2 urologist appointments annually for 5 years.

e Cost of immunotherapy were entered into the model as transition cost for the management of distant metastasis.

f Patients progressing to distant metastasis would have treatment with immunotherapy (pilimumab plus nivolumab) every 3 weeks for 4 treatments, then monthly with nivolumab for 18 months. Dr visits and blood tests every 3 weeks, with CT scans every 3 months. Low chance of admission during treatment, probably around 10% for toxicity management.

g Patients’ utility values within the progression-free survival health state were assumed to increase to the level of general population from the second month after intervention, and were based on the latest Australian EQ-5D-5L population norms which was derived from a cross-sectional survey of 9,958 general population aged 18 or older [ ].

h Considering the average age of the base case patients and the average life expectancy for Australian males who aged 65 in 2018–2020 (85.3 years) [ ], the 20-year horizon was regarded as the lifetime length.

2.3

Base case patient cohort

Characteristics of the base case cohort were modelled based on a prospective observational cohort study ( n = 41 patients with renal, lung or liver tumors) conducted in 2 metropolitan tertiary hospitals in Queensland, Australia, between July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022. Further details of this study have been previously reported [ ], and a summary of the demographic and clinical characteristics of this cohort is provided in Supplementary Table 3 . Consistent with the characteristics of this cohort, the patient population was assumed to be males aged 67 years with unilateral early stage RCCs and tumor size ≤4 cm.

2.4

Transition probabilities

Recurrence-free survival rate and metastasis-free survival rate were derived from a propensity-matched cohort study focusing upon long-term follow-up of oncologic outcomes of percutaneous MWA ( n = 59) and RA-PN ( n = 59) for the treatment of T1a RCC [ ]. Metastasis-free survival rate after local recurrence was assumed the same for both arms and was extracted from a retrospective study investigating 54 patients who underwent open nephrectomy for locally recurrent RCC [ ] ( Table 1 ). Five-year RCC-related survival rates were collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and related publications [ , ]. Annual state transition probabilities and mortality rates were then calculated using the formula: <SPAN role=presentation tabIndex=0 id=MathJax-Element-1-Frame class=MathJax style="POSITION: relative" data-mathml='1−(FutureValuePresentValue)(1/n)’>1−(𝐹𝑢𝑡𝑢𝑟𝑒𝑉𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒𝑃𝑟𝑒𝑠𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑉𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒)(1/𝑛)1−(FutureValuePresentValue)(1/n)

1 − ( F u t u r e V a l u e P r e s e n t V a l u e ) ( 1 / n )

. The background mortality rate was estimated from the 2020-2022 Australian Life Table [ ] ( Table 1 ).

2.5

Healthcare cost estimates

For cost parameters which are strongly influenced by the nature of local health systems, we selected Australian data sources so that our model could represent as closely as possible the patient heterogeneity and healthcare delivery within the Australian setting ( Table 1 ). The healthcare system perspective was limited to direct health expenditures for small renal masses management and excluded direct nonmedical costs (e.g., transportation) and informal care costs. The hospital admission costs for ablation were derived from a micro-costing analysis conducted alongside the prospective cohort study at the 2 study hospitals [ ]. The cost for RA-PN was sourced from average hospital admission cost data for robotic assisted nephrectomy, the most commonly conducted type of surgery for patients with small renal masses at 1 study hospital. Major perioperative complications were associated with increased costs, and associated costs were estimated based on AR-DRG codes. The assumed follow-up treatment pathway for patients after MWA or RA-PN is depicted Supplementary Fig. 1 . National health service reimbursement rates under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme or Medicare Benefits Schedule per course of treatment were used to assign unit costs for follow-up care items such as immunotherapy, pathology, CT scans, and drug administration [ ]. All costs were reported in 2022 Australian Dollars.

2.6

Health state utility estimates

QALYs were calculated by weighting survival time (i.e., length of life) with utility values (i.e., quality of life) that reflect health related quality of life. Patients’ utility values within the progression-free survival health state were assumed to increase to the level of general population from the second month after intervention, and were based on the latest Australian population norms [ ]. This is supported by the small but similar overall peri-operative (minor and major) complications between MWA and RA-PN for small renal tumors [ ]. We adopted utility values for local recurrence and distant metastases from published studies that most closely reflected the patient population and health states in our model ( Table 1 ) [ , ]. The EQ-5D-5L population norms in Australia was derived from the latest cross-sectional survey of 9,958 general population aged 18 or older [ ]. These studies were sourced from PubMed and the Tufts Medical Centre Cost Effectiveness Analysis Registry [ ].

3

Model evaluation and internal validation

Once the model was populated with all required input parameters, both face and internal validation was conducted. For the former, input sources and confirmation that results correspond with reality were conducted in meetings with interventional oncologists in study hospitals. For the latter, technical consistency and validity were examined by verifying equations, codes, and data against their sources by varying the values of key inputs 1 at a time and checking whether resulting outputs moved in the direction expected by clinical experts.

The primary outcome was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), defined as the incremental cost per QALY gained. It was estimated using the following formula:

ICER=CostAblation−CostRA−PNQALYAblation−QALYRA−PN

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree