Contraceptive Pills, Patches, Rings, and Injections

Anita L. Nelson

KEY WORDS

Contraceptive patches

Contraceptive vaginal rings

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA)

Injectable contraceptives

Oral contraceptives

Despite the availability of top-tier contraceptive options (such as intrauterine devices [IUDs] and implants) and the professional endorsement of their use as first-line contraceptive choices for adolescent and young adult (AYA) women, combined oral contraceptives (COCs) remain the most frequently used reversible method in the US, especially among women under 26 years of age. Newer delivery systems of estrogen-containing hormonal contraception (transdermal patches and vaginal rings) have also enjoyed great popularity among young women. Injectable contraception was extremely important in reducing adolescent pregnancy rates in the 1990s, but subsequently, lost favor as a result of the unfortunate black box warning about bone loss. Progestin-only pills are underutilized in all age groups.

This chapter will address practical issues about the selection, initiation, and continuation of each of these methods and will provide suggestions to help AYAs using these methods become more successful contraceptors. Much of the content will be based on two evidence-based guidelines from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which have significantly streamlined access to birth control, standardized contraceptive practices, and simplified identification of candidates for each method.1,2 These documents have freed practitioners from the theoretical concerns and the restrictions imposed by product labels and have provided current recommendations that enable at-risk women of all ages to choose from a more complete array of contraceptive methods. It should be noted that in these documents younger age does not enter into any consideration for use of these methods. The only age group that presents any medical concern for any method is women over 35. Therefore, recommendations made for women in this chapter apply to both adolescent women and young adult women unless otherwise specified. In the past, adolescent women had the highest rates of unintended pregnancy. Today, it is women in their early 20s who have the highest rates, so combining these two groups is logical not only from a clinical perspective but also from a public health standpoint.

The first of these publications was the US Medical Eligibility Criteria (see Figure 41.1), which rated the safety of each method for women with a wide variety of medical problems.1 Many sexually active AYAs today have serious medical problems (e.g., obesity, tobacco addiction, migraine headaches) that need to be considered when offering contraception. The effectiveness of each method must also be factored into the calculation of safety, particularly because women in this age group are more fertile and, therefore, are more apt to become pregnant and to suffer significant pregnancy complications. When grouped by first-year failure rates in typical use, the methods discussed in this chapter fall into what is considered to be second-tier contraceptive methods, that is those that fall between the top-tier long-acting reversible contraceptive methods and all the other methods in the third tier (barrier and behavioral methods).

The second document that forms the foundation for this chapter’s recommendations is the CDC’s Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraception, 2013.2 This publication removed many of the traditional, unnecessary practices that had previously created barriers to women’s contraceptive success.

There are over 90 contraceptive pills on the US market, as well as the transdermal patch, vaginal ring, and two injectables. Rather than list each product with its ingredients, this chapter will provide a brief discussion of the characteristics of each group of hormones, followed by generalizations designed to help clinicians find their ways through this cornucopia of choices.

Estrogens

There are only three forms of estrogen currently found in COCs. The transdermal and vaginal delivery systems use only one estrogen.

Mestranol is the oldest estrogen and is used only in older oral contraceptives. It is a prodrug (a compound that, on administration, undergoes chemical conversion to an active pharmacological agent) that requires hepatic conversion to create its active form ethinyl estradiol (EE). In general, ingestion of 50 µg mestranol will yield 35 to 40 µg EE. Monophasic pills with 50 µg mestranol are still marketed. There is no advantage to using formulations with this estrogen; the less predictable estrogen dose may be a disadvantage.

EE is found in virtually all US combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs). EE is fairly resistant to hepatic metabolism and, therefore, maintains therapeutic systemic levels throughout the day to provide adequate endometrial support. Because it is so potent and long acting, EE profoundly impacts hepatic production of a wide array of carrier proteins, increasing binding globulins (e.g., sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), corticosteroid-binding globulin, thyroid-binding globulin), lipid components (increasing high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and triglycerides), and coagulation factors (increasing factors in the extrinsic cascade and deceasing antifibrinolytic molecules). Together, these can impact the risks, particularly of thrombosis, with some minor impacts on metabolic profiles.

Estradiol valerate is found in one US birth control pill. The valerate ester is cleaved during intestinal absorption; the resulting estradiol is rapidly converted along familiar pathways to weaker estrogens, such as estrone (E1). In Europe, there is a monophasic formulation containing estradiol. These estrogens have considerably less hepatic impact than EE, but surrogate measures, such as antithrombin-III levels, are not reliable predictors of important clinical outcomes, such as thrombosis. Thus, longer-term studies are needed to determine the clinical significance of the differences between EE and estradiol.

Progestins

The progestin component of combined hormonal birth control methods provides most of the contraceptive effects. There are some distinctions among these groups of progestins, but they all provide solid pregnancy protection. Their differences are manifested more in potential side effect profiles.3

Norethindrone, norethindrone acetate, and ethynodiol diacetate are the progestins that have been used in oral contraceptives since the 1960s; they have a long record of safety and efficacy. In a survey of pill users from 2006 to 2010, 20% said they used pill brands with these progestins.4 Although derived from a C-19 scaffolding (19-nortestosterone), pills with these progestins rarely cause noticeable androgenic side effects. The progestin-only pill in the US has low doses of norethindrone (0.35 mg). The only clinical issue with this progestin is its relatively short half-life (8 hours), which can translate clinically into higher rates of unscheduled bleeding and spotting, especially in low-dose combined formulations with traditional 21 active pills per packet.

Norgestrel and levonorgestrel are much more potent and longer-lasting progestins introduced to provide better cycle control, particularly when combined with lower doses of estrogens. Levonorgestrel is used in pills taken by 19% of women, in the progestin-releasing IUDs and in some contraceptive implants offered overseas.4 The issue with these progestins is that they are more strongly androgenic; in preclinical studies, these progestins induce greater growth in ventral rat prostate. Clinically, this may be reflected in women by acne, oily skin, and facial hair growth. While these cosmetic impacts may not be well tolerated by a minority of users of this class of progestin, stronger androgenicity may cancel some of the estrogen-induced hepatic impacts. Studies, especially in populations with relatively high prevalence of Factor V Leiden mutations, have suggested that combined pills with these progestins may be associated with lower risk of thrombosis.5

Norgestimate and desogestrel were introduced in the US in an attempt to decrease androgenicity of the progestin while maintaining long half-life. In Europe, gestodene is also available. The first pill with a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved noncontraceptive benefit (i.e., treatment of mild-to-moderate cystic acne) contained norgestimate. The progestin in the patch (norelgestromin) is a primary metabolite of norgestimate. In the 2006 to 2010 survey, over 30% of pill users took pills containing norgestimate and another 8% used desogestrel-containing pills.4 The main metabolite of desogestrel (etonogestrel) is the progestin used in both the vaginal contraceptive ring and in the contraceptive implant. While these progestins themselves are not prothrombotic, it has been suggested that in CHC products, they may be associated with slightly increased risk of thrombosis because they do not mute the impact of EE on hepatic production of coagulation factors.6

Drospirenone (DRSP) differs from other synthetic progestins in that its pharmacological profile is closer to natural progesterone. DRSP is an analog of the potassium-sparing diuretic, spironolactone. At the 3 mg doses found in oral contraceptives, it exhibits both anti-androgenic and anti-mineralocorticoid impacts equivalent to 25 mg spirolactone. Its anti-mineralocorticoid properties counteract the estrogen-stimulated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which helps explain its benefits in reducing the physical and emotional symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). This effect is also why it should not be coadministered with drugs that increase serum potassium levels. As a mild anti-androgenic compound, DRSP enables the fullest expression of the estrogen component of the pill and, therefore, is particularly useful on-label for treatment of acne and off-label for treatment of hirsutism. However, DRSP may also permit an increase in the risk of thrombosis. Although studies have produced widely divergent results, the FDA amended the labeling of pills with DRSP to say “Based on presently available information, DRSP-containing COCs may be associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) than COCs containing the progestin levonorgestrel or some other progestins.”7 In recent years, use of DRSP-containing pills has diminished, but in the 2006 to 2010 survey, 17% of pill users reported taking pills with this progestin.4

Newer progestins, such as the currently available dienogest, and possible future candidates such as nomegestrol acetate so significantly suppress the endometrium that they can provide good cycle control when coupled with estradiol in lieu of EE. The multiphasic formulation containing dienogest is the only oral contraceptive that is FDA-approved for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a derivative of progesterone, not testosterone, and has two different formulations as microcrystals suspended in an aqueous solution for contraception as intramuscular or subcutaneous injections.

Progestin-only pills—There is only one such product available in the US at this time, although many generic versions are sold. Each pill contains 0.35 mg norethindrone. The pack contains 28 active pills and no placebo pills. These pills are the safest of all available oral contraceptives; they have few contraindications and are as effective as combination pills in typical use.

Special Features and Additives of Oral Contraceptives

Some formulations add iron supplements to the placebo pills.

Two formulations include levomefolate calcium in each pill to raise serum folate levels to a therapeutic range in an attempt to reduce risk of neural tube defects should pregnancy occur while a woman is taking pills or shortly after she stops taking them.

One formulation is chewable.

Formulations/Delivery Systems for CHCs

Combined Oral Contraceptives

COC options include:

Dosing patterns in single-pill packets vary in the following patterns:

Monophasic formulations—each active pill has the same doses of hormones as all the other active pills. Monophasic formulations may simplify missed pill instructions.

Multiphasic formulations—the dose of estrogen and/or progestin in different active pills varies. Multiphasic formulations reduce the total hormonal exposure over a cycle and may be useful in controlling unscheduled bleeding seen with some monophasic formulations.

Number of active pills and placebo pills in traditional 28-pill packs varies:

21/7: classic pattern of 21 active pills and 7 placebo pills

21/2/5: 21 active pills, 2 placebo pills, and 5 tablets with 10 µg EE

24/4: 24 active pills, 4 placebo pills

24/2/2: 24 active pills, 2 placebos, 2 low-dose estrogen-only pills

Extended-cycle formulations

84/7: 84 active pills followed by 7 placebo pills or

84/7: 84 active pills followed by 7 tablets each with 10 µg EE

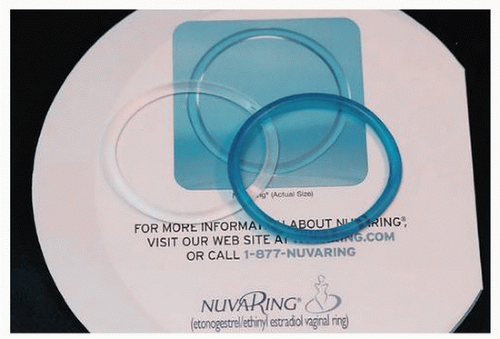

Vaginal Contraceptive Ring

Labeled for use as a 21-day device that is then removed for 7 days to recreate the 21/7 pattern of traditional COC, the ring actually contains sufficient hormonal reserve for 6 weeks for both

normal-weight and obese women (Fig. 43.1).8 Therefore, it can also be prescribed as an extended-cycle (continuous) once-a-month method. Over a 24-hour period, the amount of progestin released from the ring (area under the curve) is equivalent to that absorbed from oral contraceptives, but area under the curve for EE is half of that seen with oral contraceptives. Thus, the amount of estrogen absorbed via the ring is substantially less. Despite the lower levels of estrogen, cycle control with the ring was found to be superior to that of COCs.9 The most recent FDA review of this issue concluded that the risk of VTE with the ring was equivalent to COCs.

normal-weight and obese women (Fig. 43.1).8 Therefore, it can also be prescribed as an extended-cycle (continuous) once-a-month method. Over a 24-hour period, the amount of progestin released from the ring (area under the curve) is equivalent to that absorbed from oral contraceptives, but area under the curve for EE is half of that seen with oral contraceptives. Thus, the amount of estrogen absorbed via the ring is substantially less. Despite the lower levels of estrogen, cycle control with the ring was found to be superior to that of COCs.9 The most recent FDA review of this issue concluded that the risk of VTE with the ring was equivalent to COCs.

Instructions for ring use are quite straightforward; use requires that the consumer feel comfortable touching herself. Tampon users are often the most willing to try this method. For women who have any difficulty placing the ring, a smooth-ridge tampon insertion tube can be used (after removal of the tampon) to place the ring flat against the vaginal walls anywhere in the upper vagina. In that position, only 30% of partners report they can detect the ring’s presence during coitus and only a fraction of those women need to remove the ring for partner comfort. Women need to remember that in order to maintain efficacy, the ring may be removed for no more than 3 hours in any 24-hour period. The pouch that the ring comes in serves as a temporary storage area and also should be used to dispose of the ring at the end of its useful life. The ring increases vaginal secretions, which can be helpful to provide lubrication during intercourse and it increases lactobacillus numbers, which reduces recurrences of bacterial vaginosis.10

Transdermal Contraceptive Patch

To date, the contraceptive patch is a unique product with EE and norelgestromin (metabolite of norgestimate). The user applies one patch per week at different sites on her abdomen, back, chest (not breasts) or on her upper arm for three consecutive weeks followed by one patch-free week. Occasionally, extending the use of consecutive active patches for a few weeks for specific indications is reasonable, but ongoing extended-cycle use is not recommended. Only one study has investigated the safety and efficacy of 12 weeks of uninterrupted use; it found that serum levels of EE increased with time. In the clinical trials, greater numbers of women of all ages reported correct use with the patch than with the pill, but the greatest improvement was found in women aged 18 to 19. With initial use, breast tenderness was noted in 20% of women, but in subsequent cycles, patch users reported this no more frequently than COC users.

The patch has been associated with a higher risk of VTE, which was plausible because 24-hour area-under-the-curve levels of EE with the patch are about 60% higher than those found with use of 35 µg oral contraceptives. Although epidemiological studies have not consistently reported higher rates of VTE, the product label suggests that patch users might face greater VTE risks than by lower-dose pill users, but those VTE risks are lower than those faced by women in pregnancy.

Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate

There are two branded formulations of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in the US—one administered intramuscularly (IM) (DMPA 150 mg IM) and one that is given subcutaneously (Sub-Q) (DMPA 104 mg/0.6 cc Sub-Q). These products differ not only in amount of DMPA and the intended site of injection, but also in the buffers used in the injection fluid. As a result, the two formulations are not interchangeable with each other, nor are they interchangeable with the 425 mg/mL DMPA product used in chemotherapy. Generic products exist for the IM version. Efficacy for either DMPA is not affected by body mass index (BMI). Reinjections are scheduled every 11 to 13 weeks for the DMPA-IM and every 12 to 14 weeks for the DMPA Sub-Q. Serum levels of medroxyprogesterone acetate remain detectable in some users as late as 7 to 9 months after injection. There is slow absorption (not steady state) of DMPA from the injection site; some metabolites are biologically active and are stored within the adipose tissue. Return to fertility averages 7 to 9 months after injection; it is independent of the number of injections the woman has had, but is generally slower in women with more adiposity.

Efficacy

There are two important measures of contraceptive efficacy:

“Perfect Use” Failure Rate

Estimates of the potential pregnancy protection afforded with correct and consistent use of a method during the first year of use (“perfect use” failure rate). This statistic is derived from data from clinical trials after adjustments have been made for inconsistent use. For DMPA, the Pearl index (failure rate) with correct and consistent use is 0.2%, while all the other second-tier methods have failure rates with correct and consistent use of 0.3%.

Typical Use Failure Rate

The first-year failure rates with typical use are obtained from the National Survey of Family Growth—a detailed survey conducted every 5 years. First-year typical use failure rates for each of these second-tier methods are much higher than those seen in clinical trials. For the injection DMPA, the first-year typical use failure rate is 6%, while the typical use failure rates of all the other hormonal methods in this category are 9%. It is important to note that, contrary to common belief, the failure rates in typical use for the progestin-only pills are no higher than those found with the estrogen-containing pills. On the other hand, it might be expected that with the convenience of non-daily dosing, the patch and ring would have lower failure rates than the daily pills, but data have not yet substantiated that hypothesis. The gap between the pregnancy protection that is possible with each of these methods and what is actually achieved demonstrates the impact of inconsistent use (Table 43.1).

Other Considerations

Impact of Formulation on Effectiveness: Recent work suggests that some formulations of COCs may be more effective in typical use than others; extended-cycle formulations have lower failure rates than 24/4 formulations and the 24/4 formulations have lower failure rates than traditional 21/7 formulations.11

Impact of BMI on Effectiveness: The potential efficacy of pills and vaginal rings is not reduced in women with higher BMI,12,13 even though absorption of progestin has been shown to be slower in obese women compared to normal-weight women.14 The explanation for the fact that some studies showed higher failure rates among obese

women may rest in the observation that obese women were significantly more likely not to take their pills than were lighter women. When the study findings were adjusted for pill use, obese women had no higher rates of ovulation than the normal-weight women.15 The efficacy of the patch may be significantly diminished in women weighing more than 198 pounds.

women may rest in the observation that obese women were significantly more likely not to take their pills than were lighter women. When the study findings were adjusted for pill use, obese women had no higher rates of ovulation than the normal-weight women.15 The efficacy of the patch may be significantly diminished in women weighing more than 198 pounds.

|

Mechanisms of Action

What These Methods to Not Do

None of these methods is an abortifacient.

None disrupts an established pregnancy.

There is also no convincing evidence that any of these methods interferes with implantation of a fertilized egg, although these methods all induce changes in the endometrium that affect bleeding patterns.

What These Methods Do to Prevent Pregnancy

Overall, progestins provide contraception by several different mechanisms, depending on the dose, potency of the progestins, and the delivery system used.

Every progestin consistently thickens cervical mucus, which blocks sperm penetration into the upper genital tract.

Progestins also alter tubal transport time, which slows transit of both the ovum and sperm.

Ovulation inhibition varies with each method:

Progestin-only pills available in the US prevent ovulation in 40% to 60% of cycles.

Mid-dose birth control pills/patches/rings suppress ovulation in >90% of cycles.

DMPA provides almost complete ovulation suppression.

Estrogen, which is generally added for cycle control, may also blunt follicular stimulating hormone release.

Drug-Drug Interactions

Drugs that induce hepatic enzymes can alter the serum concentration of estrogen and/or progestin of these contraceptives, which may increase failure rates or result in excessive circulating hormone levels. It should be noted that the only drug known to affect DMPA efficacy is aminoglutethimide. There is also the possibility that sex steroids could influence the metabolism of other drugs and alter their efficacy. Other potential mechanisms for drug-drug interactions, such as enterohepatic recirculation or induction of binding globulins, have either no or insignificant clinical impacts compared to the background interindividual variability observed in the absorption and metabolism of these compounds.

Anticonvulsants

This is the most common class of drugs known to have reciprocal impacts on progestin and estrogen. Many of these drugs are used for other indications, such as treatment of bipolar disease, neuropathic pain, migraines, and posttraumatic stress syndrome. Barbiturates (phenobarbital and primidone), phenytoin, carbamazepine, felbamate, and topiramate all decrease circulating levels of both estrogen and progestin in oral contraceptives, pills, and patches (Table 43.2). If a COC is selected for women using enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants, formulations with at least 35 µg EE and shortened or no pill-free intervals should be used. DMPA concentrations are not significantly affected by any of these drugs and may be a better contraceptive option. Many of the newer anticonvulsant drugs do not induce hepatic enzyme activity (Table 43.3) and, therefore, do not affect estrogen or progestin levels. Lamotrigine presents unique challenges. While lamotrigine does not affect the levels of contraceptive hormones, lamotrigine’s own metabolic clearance is significantly increased by estrogens and circulating levels of lamotrigine are reduced to 41% to 64% of those seen without estrogen-containing contraceptives. This means that the dose of lamotrigine, when used as monotherapy, must be significantly increased (i.e., doubled) while the woman is taking active pills, to avoid breakthrough seizures. The doses need to be decreased significantly when she stops pill use, to avoid overdosing. For this reason, the number of pill-free days needs to be minimized between cycles. Individual monitoring is needed to calculate the doses of lamotrigine each woman will need when on CHC. Other methods, such as DMPA, appear safer to use. Of note, therapies that combine a non-enzyme-inducing anticonvulsant, such as valproic acid, with lamotrigine do not require any dosing modifications for lamotrigine when the woman uses estrogen-containing contraceptives.

TABLE 43.2 Impact of Enzyme-Inducing Anticonvulsants on Systemic Levels of Sex Steroids40 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree