CASE HISTORY

Maria is a 43-year old mother of four children with a 21-year history of Type 2 diabetes and an 8-year history of hypertension. She has recently started metformin as prescribed by her physician. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 36 kg/m2, blood pressure of 142/88 mmHg, and a fasting blood glucose of 7.6 mmol/L (137 mg/dL). She presents for a visit 4 weeks postpartum. She is both breast and bottle feeding. She used condoms before her first three pregnancies and the progestin-only pill between her third and fourth pregnancies, although she admits to somewhat variable compliance. She thinks she would like to resume using one of these methods, and that her family is probably complete. You counsel her regarding her contraceptive options, emphasizing efficacy, including sterilization and intrauterine devices, but also the possibility of her resuming the progestin-only contraceptive method or using condoms.

- Why is effective contraception so important in relation to diabetes in liregnancy?

- When should women be advised to start contraception after delivery?

- What are the tylies of contracelitives available?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of each of these methods?

- What are the issues with contraception and breastfeeding?

BACKGROUND

The association of hyperglycemia during embryogenesis with an increased dose-response risk of both major and minor congenital malformations1 is now clearly established and underscores the importance of offering women with pregestational diabetes, and those with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), a safe and reliable contraceptive method both in the planning stage and as soon as possible after delivery. All women with diabetes should receive preconception counseling and achieve euglycemia prior to attempting conception. Using an effective method of contraception during this period is crucial. During pregnancy, postpartum contraceptive options and breastfeeding need to be discussed to achieve seamless contraception that begins after delivery. Exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months postpartum does provide pregnancy prevention and decreases the risk for obesity and metabolic syndrome in the offspring. However, by the time of the traditional 6-week postpartum visit, over 25% of women who intend to breastfeed may have abandoned breastfeeding, and only 35% are exclusively breastfeeding.2. Within six weeks of delivery, up to 5% of non breastfeeding women will ovulate, putting them at risk for subsequent pregnancy.3 Accordingly, it is important that discussions about contraception are held prior to postpartum hospital discharge and that plans are finalized at the 3-6-week postpartum visit.

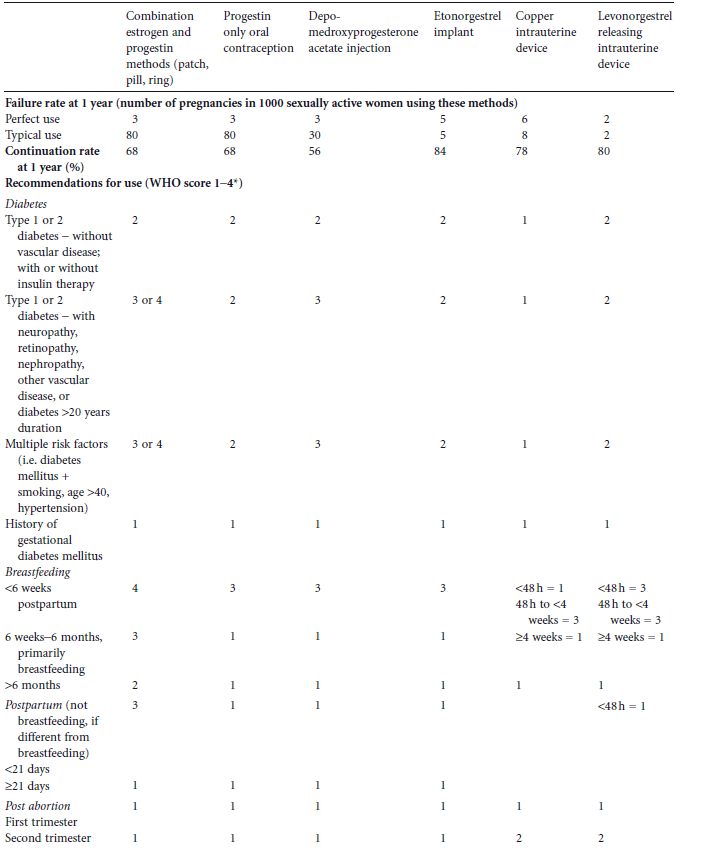

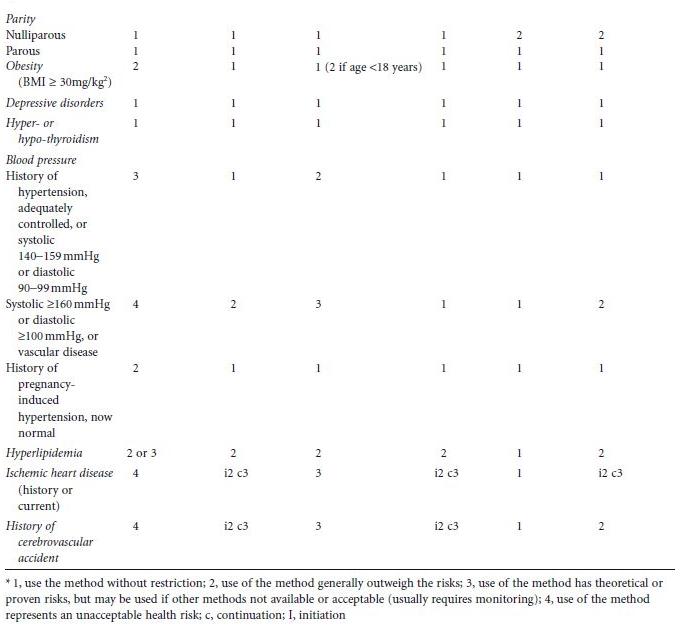

Contraceptive choices depend on whether and when a woman desires to become pregnant. For women who do not desire pregnancy in the near future, longacting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, e.g. intrauterine contraceptives and hormonal implants, are the most efficacious because they are not coitus dependent and do not require vigilance on the part of the patient. Continuation rates, efficacy rates, and World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations of the various methods are detailed in Table 23.1.4,5 Studies examining contraceptive use in diabetic or prediabetic women have generally been retrospective and limited to shortterm use.6 Thus, many of the recommendations have been necessarily extrapolated from epidemiologic studies and clinical trials in nondiabetic women, and WHO classification of categories of contraceptive risk.4 Most of the data available are a combination of level C evidence, expert opinion, and practitioner experience. While more contraceptive trials in diabetic women are needed, data from existing studies support the use of most contraceptive methods. Additionally, morbidity and mortality risks of pregnancy far outweigh those for using the most effective forms of contraception. Many women, including those with diabetes, have misconceptions about family planning methods. Eliciting concerns from the patient and providing evidencebased education may improve uptake of effective contraceptive methods and adherence.

This chapter will review contraception in women with Type 1, and Type 2 diabetes, and previous GDM. A simple questionbased approach to individualized counseling is used, considering diabetic complications, comorbidities, metabolic effects, and lifestyle demands.

HOW MANY MORE CHILDREN WOULD YOU LIKE TO HAVE?

If the woman is convinced that her family is complete, two permanent options are available: vasectomy or female tubal sterilization. These methods require the patient to be counseled as to the permanent nature of the procedure and are generally not recommended for nulliparous women.

Vasectomy

The safest method for the woman with diabetes is for her male partner to have a vasectomy, which can be performed as an outpatient procedure. By interrupting the vas deferens, the passage of sperm is prevented from entering the female reproductive tract. The perfect use failure rate in the first year is reported as 0.1%, but studies reveal a failure rate of 0.0–0.74% at 1 year with a cumulative failure rate of 1.1% at 5 years.5 The higher failure rate is usually considered secondary to the failure to use an alternate method of contraception until two consecutive sperm samples reveal no motile sperm. The use of this method does require a cooperative partner.

Female sterilization

If a cesarean delivery is planned, tubal sterilization can occur at that time. However, if the cesarean is unplanned, then even if counseling had taken place during pregnancy, there is the risk of a hurried decision which must be balanced against the risks of a subsequent sterilization operation. The most effective methods are postpartum partial salpingectomy and interval laparoscopic sterilization, both with a 10-year cumulative failure rate of 0.75%.7 While sterilization is safe and effective, diabetes is an independent risk factor (adjusted OR 4.5) for one or more postoperative complications.8

A newer method of female sterilization has been developed that can be performed hysteroscopically in an outpatient setting without anesthesia, by inserting devices into the fallopian tubes that cause severe local inflammation. A hysterosalpingogram is advised at 3 months to document success. Data about this method in diabetic women are limited.

Table 23.1 Contraceptive failure and continuation rates at 1 year and 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for hormonal and long-acting reversible contraceptive use in women with diabetes mellitus and associated conditions with 2008 updates. (Adapted from World Health Organization4 and Trussel5.)

ARE YOU INTERESTED IN USING A CONTRACEPTIVE METHOD THAT YOU DO NOT NEED TO THINK A BOUT ON A REGULAR BASIS?

Reversible longacting methods of contraception (LARC) are recommended for use in women with diabetes and are also advocated worldwide by family planning leaders. Two main categories exist: intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUDs) and hormonal contraceptive implants. Their efficacy rivals that of permanent sterilization and they can be used by most women with diabetes, including during breastfeeding. Both are rapidly reversible. Because they require placement and removal by a healthcare professional, continuation rates are higher than for any other form of reversible contraception (see Table 23.1). This provides the healthcare provider with an opportunity to help patients achieve optimum glycemic control prior to removal for a desired pregnancy. While most diabetic women can safely use all LARC methods, various medical problems unrelated to diabetes, such as current breast cancer, may prohibit the use of hormonal LARC methods.

Intrauterine c ontraception

IUDs have little or no systemic or metabolic effects, and can be used in diabetic women with obesity, vascular disease, hypertension, retinopathy or hyperlipidemia. Most women with diabetes are excellent candidates for IUDs and patient selection follows the same guidelines as for nondiabetic women (e.g. no evidence of current pelvic inflammatory disease). Two types of IUDs are currently available, one which releases copper (Cu–IUD) and the other, a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG–IUD). In an asymptomatic woman who does not have a mucopurulent cervicitis, cervical PCR for gonorrhea and chlamydia may be obtained at the time of insertion, but these results must be followed up for treatment in case of a positive culture. While IUDs are inserted using an aseptic technique, there is a slight risk for infection in the first 3 weeks after insertion. After this time, the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease is no longer increased compared to non-IUD users. Because the overall risk of infection is low in an asymptomatic woman, antibiotic prophylaxis is not routinely recommended.9 IUDs may be placed in women with a remote history of pelvic inflammatory disease, nulliparous women, and after a non-septic spontaneous or elective abortion. If it is considered probable that the woman will return for insertion postpartum, then arrangements may be made for IUDs to be inserted 4–6 weeks after delivery. Alternatively, they may be inserted at cesarean delivery or within 48 hours after delivery, although this has been associated with an increased expulsion rate10 when compared to the very low rate at 4–6 weeks post delivery.11

Follow-up studies reveal that mean weight gain after 5 years of use, at 2.4 kg in both hormonal and non-hormonal IUD users, is no different from what would be expected in the general population.12 Although studies in diabetic women are limited, 12-month conception rates are comparable to the general population after discon-tinuation.12 With regard to metabolic effects, in a 1-year randomized trial in diabetic women comparing the LNG -IUD with the Cu-IUD, no significant differences were found in fasting glucose levels, glycosylated hemoglobin or daily insulin requirements at 6 weeks, 6 months, or 12 months post insertion.13

Copper intrauterine device

The Cu-IUD is an excellent method of contraception for most women with diabetes. It is metabolically neutral with a 12-year cumulative pregnancy risk of 1.9%.14 Prospective studies examining Cu-IUD use in women with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes have found no increase in pelvic inflammatory disease or any decrease in efficacy.15,16 The use of Cu-IUDs is associated with increased menstrual blood loss compared with controls and users of the LNG-IUD, making it a less desirable IUD for diabetic women with anemia of chronic disease or renal disease, heavy menstrual bleeding or on anticoagulation therapy.17

Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device

In addition to its excellent efficacy, the LNG-IUD offers many non-contraceptive benefits, including protection from endometrial cancer, which is more common among obese women.17 While it is protective against the development of anemia, there is often intermittent light vaginal bleeding in the first few months after insertion. Thereafter, menstrual blood loss is generally 70–90% less than before insertion. The levonorgestrel released into the uterine cavity reaches only 5% of the plasma levels observed with a 105-μg dose of oral levonorgestrel, resulting in minimal systemic effects. In a study of 48 women (mean age 44 years), there was a mean decrease in diastolic blood pressure with no significant change in systolic blood pressure, lipid profile, or liver function tests. However, at 1-year follow-up there was an increase in the mean fasting blood glucose concentration, although as the study was uncontrolled it is unclear if the IUD had an effect on this predestined metabolic decline.18

Progestin-releasing implants

The only progestin-releasing implant available in the US contains 68 mg of etonorgestrel (ENG-I). It consists of a single rod placed subdermally in the non-dominant arm by a trained inserter. It may be associated with irregular light bleeding and is effective for at least 3 years. Currently no studies address its use in diabetic women. In one study of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and insulin resistance, a group at high risk of developing Type 2 diabetes, there was a decline in insulin action as measured by the homeostasis model (HOMA) at 3–12 months from baseline, but no comparison was made with other contraceptive methods.19 In healthy women, the implant was associated with an increase in insulin resistance.20 While there were no significant changes in BMI, daily insulin requirement, mean HbA1c or retinal changes, Vicente et al showed a statistically significant decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), total serum cholesterol (TC), and triglyceride levels. The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels and HDL/TC ratio did not change, while albuminuria decreased.21 However, the ENG-I is a better alternative to pregnancy in diabetic women who have difficulty complying with non-LARC contraceptive methods.

ARE YOU INTERESTED IN USING A CONTRACEPTIVE PILL AND A RE N OT IMMEDIATELY POSTPARTUM?

The combined oral contraceptive (COC) preparations available today contain low doses of estrogen and less androgenic progestins, and generally result in no or minimal effects on glucose tolerance and favorable changes in serum lipids. In diabetic women, these possible metabolic effects become important considerations when comorbidities, particularly hypertension or hyper-lipidemia, are present. Evaluation of fasting serum lipids and blood pressure allows the selection of the best formulation with the least possible metabolic effect. As a rule, the lowest possible dose and potency formulation should be selected. Estrogen has a mixed effect on serum lipids. While producing desirable effects on HDL and LDL cholesterol levels, estrogen can also increase serum triglyceride levels, which often are already elevated in women with Type 2 diabetes, and can also be related to poor glycemic control and thyroid disease. Estrogen is also associated with a dose-dependent increase in globulin production along with an increase in coagulation factors and angiotensin levels, thereby increasing thromboembolic risk and producing a slight increase in mean arterial blood pressure.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree