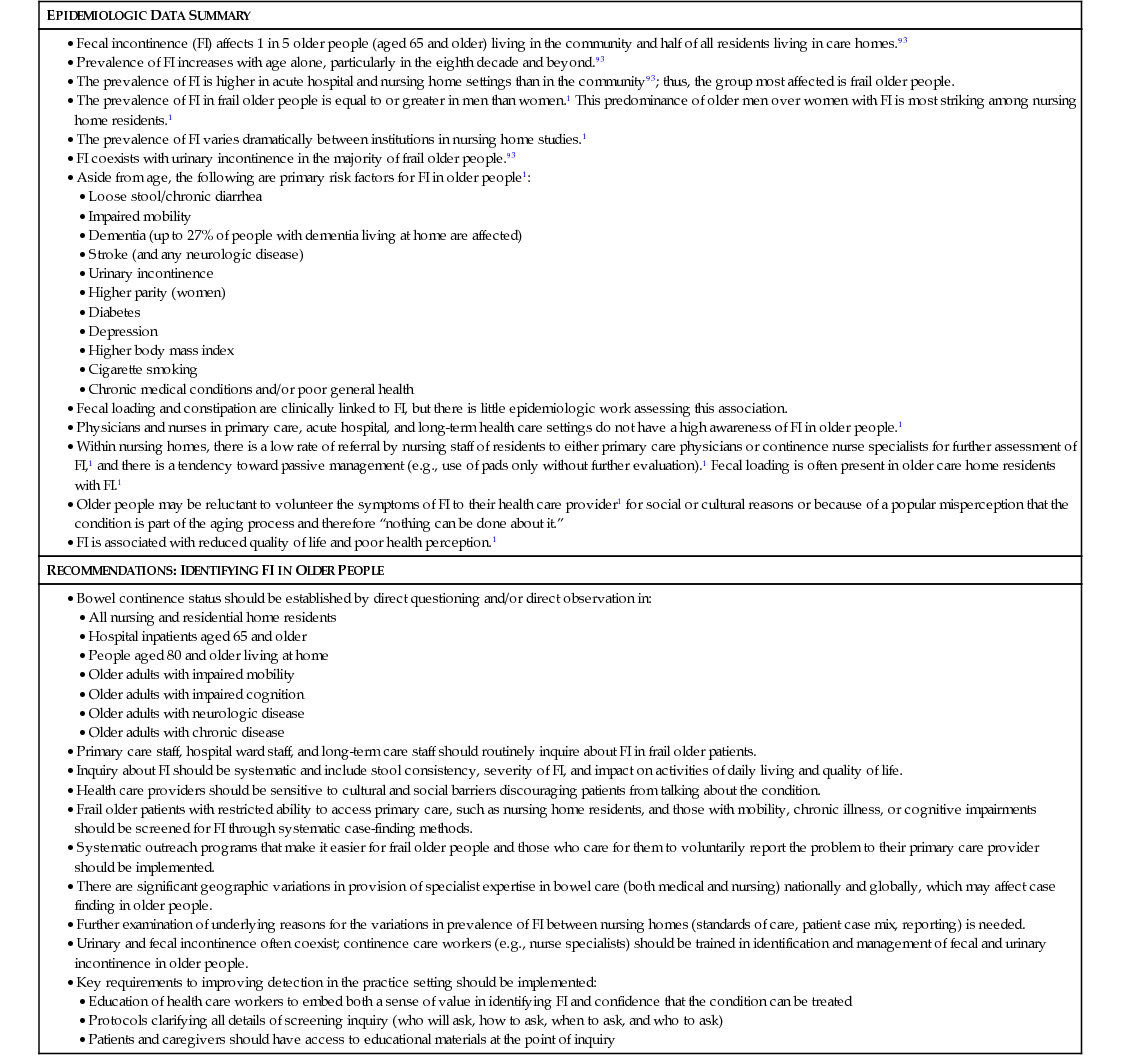

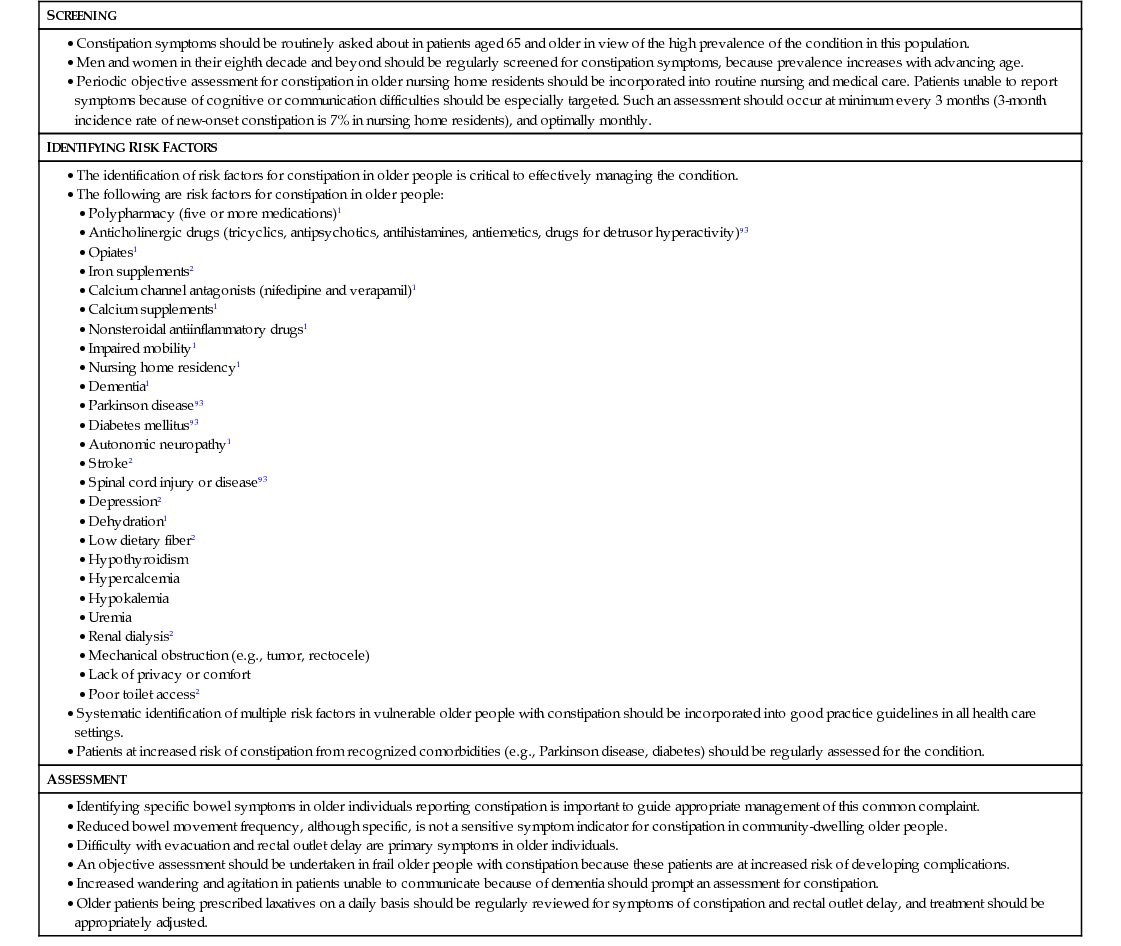

Danielle Harari Fecal incontinence (FI) in older people is a distressing and socially isolating symptom and increases the risk of morbidity,1,2 mortality,3,4 and dependency.2,4 Many older individuals with FI will not volunteer the problem to their general practitioner or nurse. Regrettably, health care providers do not routinely inquire about the symptom, which is why it is a routine prompt in a standard comprehensive geriatric assessment. This “hidden problem” can lead to a downward spiral of psychological distress, dependency, and poor health. The condition can especially take its toll on informal caregivers of home-dwelling patients,5 with FI being a leading reason for requesting nursing home placement.6,7 Even when older people are noted by health care professionals to have FI, the condition is often managed passively (e.g., pads provision without assessment). Current surveys show limited awareness of appropriate assessment and treatment options among primary care physicians.8 The importance of identifying treatable causes of FI in frail older people is strongly emphasized in national and international guidance,7,9–12 but successive audit shows that adherence to such guidance is generally poor, with nonintegrated services, and suboptimal delivery by professionals of even basic assessment and care.13–15 Constipation is a common concern for adults as they age beyond 60 years, reflected by a notable increase in primary care consultations and burgeoning laxative use. Older people reporting constipation are more likely to have anxiety, depression, and poor health perception. Qualitative studies show older adults feel doctors can be dismissive about the problem and that useful and empathic professional advice is hard to find,16 and this is confirmed in primary care studies that reveal that general practitioners view constipation as less important than other conditions (such as diabetes).17 Clinical constipation in frail individuals can lead to significant complications such as fecal impaction, FI, and urinary retention precipitating hospital admission. Constipation and FI are costly conditions, with high expenditure, including laxative spending and nursing time.5 For instance, it is estimated that 80% of community nurses working with older people in the United Kingdom are managing constipation (particularly fecal impaction) as part of their caseload. A 2014 health care utilization study of patients with chronic constipation (mean age 64) in Sweden documented an average of 2.4 constipation-related health care contacts per year at an annual cost of 951 Euros per patient.18 The World Health Organization (WHO) International Consultation on Incontinence defines FI as “involuntary loss of liquid or solid stool that is a social or hygienic problem.”10 There is, however, a lack of standardization in defining FI in published prevalence studies, hindering cross-study comparisons. Most community-based studies examine prevalence of FI occurring at least once over the previous year, which may overestimate prevalence but also provide the upper limit for FI occurrence. Nursing home studies mostly measure weekly or monthly occurrence. Systematic reviews examining FI prevalence have highlighted the need for consensus on definitions.19,20 A study of women mostly aged 60 years and older with FI looked at patient-preferred terminology for FI symptoms: important outcomes were predictability, awareness, ability to wipe, and burning discomfort, in addition to the usual primary outcomes of frequency, amount of leakage, and “bother.”21 Definitions of constipation in older people in medical and nursing literature have also been inconsistent. Studies of older people have defined constipation by subjective self-report, specific bowel-related symptoms, or by daily laxative use. Self-reported constipation (e.g., “Do you have recurrent constipation?”) often means different things to different individuals.14 It is now increasingly required in both clinical practice and research to use standardized definitions for constipation based on specific symptoms (Rome III criteria)22–25 (Table 105-1). Important constipation subtypes affecting older people, such as rectal outlet delay and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C), are easier to identify by using standard definitions.22,24,25 Rome criteria are symptom-based: objective assessment relies on finding fecal loading in the rectum, colon, or both. Such objective assessment is particularly important in frail older people in whom constipation can be underestimated (Table 105-2). TABLE 105-1 Definitions of Constipation TABLE 105-2 Factors Potentially Leading to Underestimation of Constipation and Fecal Incontinence in Frail Older People Frail older people may: Constipation is a hugely prevalent problem in older people. Approximately 63 million people in North America meet the Rome III criteria for constipation, with a disproportionate number being older than 65 years.26 Age is strongly associated with nonspecific self-reporting of constipation.27–29 It is therefore striking that the report of infrequent bowel movements (two or fewer per week) is no more prevalent in older than younger people in community-based studies. • Only 1% to 7% of both younger and older people report two or fewer bowel movements a week.27,29,30 • This consistent bowel pattern across age groups persists even after statistical adjustment for greater laxative use among older people.27 • Of older people complaining of constipation, less than 10% report two or fewer weekly bowel movements, and more than 50% move their bowels daily.29,31 • In contrast, two thirds of older people have persistent straining, and 39% report passage of hard stools.31 The symptoms predominantly underlying self-reported constipation in older people tend not to be infrequent bowel movements but straining and passing hard stools. Difficult rectal evacuation is a primary cause of constipation in older people. Among community-dwelling people aged 65 and older, 21% have rectal outlet delay (see Table 105-1),32 and many describe the need to self-evacuate.16,32 Two thirds of nursing home residents taking laxatives still report frequent straining.33 Among these frailer individuals, difficult evacuation can lead to recurrent rectal impaction and overflow. Fecal impaction was a primary diagnosis in 27% of acutely hospitalized geriatric patients admitted over the course of 1 year in the United Kingdom,34 and a survey of patients with FI found that fecal loading was present in 57% of older acute hospital inpatients and 70% of care home residents.35 Frail older people have a higher prevalence of two or fewer weekly bowel movements, affecting one third of care home residents reporting constipation.36 Up to 80% of care home residents are constipated according to Rome III criteria,37 a surprising figure considering that 50% to 74% of long-term care residents use daily laxatives.36,37 A recent nationwide care home study in Spain similarly found a 71% prevalence of chronic constipation, of whom only 43% had the condition controlled with 8% rectally impacted on digital examination.38 Acute hospital admission is in itself a risk factor for constipation—43% of adult patients acutely admitted to medical wards developed constipation during the first 3 days of hospital stay (incidence rate 143/1000 patient days), with older people being more severely affected.39 Table 105-3 summarizes data on prevalence and risk factors in FI. Meta-regression analysis of prevalence studies in community-dwelling people shows that age has a significant influence on rates of solid and liquid FI.20 Prevalence is equal between genders in older people, except in the care home setting, where it is greater in men.40–43 A prospective U.S. population-based study in community-dwelling men and women aged 65 and older showed a high incidence rate for new FI of 17% over 4 years, strengthening the case for screening of older patients in primary care.44 In U.K. primary care, the rates of first diagnosis for FI in patients older than 60 years was 11% in people with dementia and 3% in those without dementia.45 There is equal reason to screen care home residents. A prospective study in French nursing home residents3 found a baseline FI prevalence of 54% and a 10-month incidence in those continent at a baseline of 20%. New-onset FI was transient (less than 5 days) in 62% and long standing in 38%. In the latter group, 1-year mortality was 26% compared with 7% in those who remained continent. TABLE 105-3 Epidemiology of Fecal Incontinence in Older People and Recommendations for Identifying Cases The prevalence of FI varies according to the general health of the study population and therefore by proxy to the study setting. • Community: 6% to 12% in adults older than 65 years and 18% to 29% in those older than 80 years4,5,40,46–54 • Acute hospital: 14% to 33% in adults older than 65 years55,56 Of note, U.K. care home studies have shown wide variations in prevalence between individual homes,42,50 which may well be more reflective of different standards of care rather than of different patient characteristics. A national study of care home in Norway found an overall prevalence for FI of 47% with similar risk factors of diarrhea, dementia, and longer residential stay, but the risk was reduced in residents needing help to transfer between bed and chair as compared to those transferring independently; it is important that increased risk of FI (and indeed falls) should not promote less assistance with toilet mobility in care settings.57 These prevalence data represent case-finding statistics within epidemiologic studies, but in real clinical settings, FI is often overlooked. Reasons for this include that older people do not seek help (“it is embarrassing” and “nothing that can be done”) and that providers do not find cases and do not follow through when the problem is identified. In British primary care surveys, less than 50% of home-dwelling older people with FI (or their caregivers) reported discussing the problem with a health care professional.58 Recent U.S. surveys of consultation and screening in older women with FI show that more than two thirds do not seek help,59 they have little knowledge about availability and effectiveness of treatments, and most would prefer physicians to ask them directly about the symptom.60 Younger women are more likely to seek help for less severe FI symptoms than older women,60,61 yet even in younger cohorts, most cases of FI are still not recognized by general practitioners.62 Primary care studies showing incidence of FI in home-dwelling people with dementia highlight the opportunity to build early intervention and support pathways to avoid incontinence being a factor for insitituionalization.63 Poor provider awareness of FI is just as prevalent among older adults in institutions as it is in home-dwelling adults despite greater opportunity for patient observation. In the acute hospital setting, only one in six patients reporting FI have the symptom documented by ward nursing staff,64 and care home nursing staff are aware of FI in only half of those residents self-reporting the condition.36 Professional ignorance about how to treat FI may, in part, underlie this poor provider awareness of the condition. A U.K. care home survey found that trained staff cited advanced age as the main cause of both urinary and fecal incontinence.65 Auditing bowel care in care homes to improve quality of care may seem like a solution, but this proved challenging in a recent high-profile nationwide audit of urinary and fecal incontinence care in older people in the United Kingdom.14,15 Many care homes declined participation, and those who did partake generally reported hampered data collection (because of limited access to clinical records and information technology) and staff shortages. The audit showed that patients admitted to these care homes with preexisting FI tended to be placed on a containment management plan rather than being assessed for causes and possible treatment, and this was despite having good access to continence specialist care. On a similar theme, a U.S. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Statement commented that health care provider education alone is not enough to improve the identification of adults with FI and recommended key requirements to improve detection in the practice setting (see Table 105-3).7 Urinary incontinence is strongly linked to FI, with 50% to 70% coexistence in community-based studies.1,41,48,66 Perhaps unsurprisingly, diarrhea or loose stool is a strong predictor for FI in all settings, but what is striking is the prevalence of chronic diarrhea in frail older people.1,5,43,50 Medical comorbidity and physical disability are equivalent or greater than age in strength of assocation.1,2,5,41,66 A cohort study of community-dwelling patients aged 65 and older found that severe FI (at least once weekly) was associated with increased mortality after 42 months, independent of age, gender, and poor general health.4 Depression is repeatedly linked in cross-sectional studies, probably as both cause and effect.1,48,41 A 15-year study showed a strong association between self-reported depression and persistent constipation in community-dwelling older women.67 Independent factors for FI in acutely hospitalized patients (in order of strength of association) are loose/liquid stool consistency, illness severity, and older age.56 In older hospital inpatients, contributing factors are fecal loading (57%), functional disability (83%), loose stools (67%), and cognitive impairment (43%)35; those with loose stools and less comorbidity are more likely to have transient FI with resolution after 3 months. Most risk factor studies for constipation are cross-sectional, but one prospective study examined baseline characteristics predictive of new-onset constipation (two or fewer bowel movements per week or persistent straining) in older U.S. nursing home patients.68 Seven percent (n = 1291) developed constipation over a 3-month period. Independent predictors were poor consumption of fluids, pneumonia, Parkinson disease, decreased bed mobility, more than five medications, dementia, hypothyroidism, white race, allergies, arthritis, and hypertension (the latter three conditions were postulated to be associated primarily because of the constipating effect of drugs used to treat them). What is evident is that many of these factors are potentially modifiable. Table 105-4 summarizes practice guidance in constipation based on the epidemiologic data described in this section. TABLE 105-4 Practice Guidance for Constipation Based on Epidemiologic Evidence Greater physical activity (including regular walking) is associated with less constipation in older people living at home.28,69 Reduced mobility is the strongest independent correlate (following adjustment for age and comorbidities) of heavy laxative use among nursing home residents,70 and gut transit time in bedridden older subjects can be as long as 3 weeks.71 Exercise increases colonic propulsive activity (“joggers diarrhea”), especially when measured postprandially.72 In a survey of younger women (36 to 61 years), daily physical activity was associated with less constipation (constipation measured as two or fewer bowel movements per week), and the association strengthened with increased frequency of physical activity.73 This leads to speculation that increasing physical activity in adulthood may reduce the likelihood of constipation problems in older age. Epidemiologic studies in older people have repeatedly shown that poor mobility is also a strong risk factor for FI after adjustment for other variables.2,3,5,41,43 Polypharmacy itself increases the risk of constipation in older patients, particularly in nursing homes where each individual takes an average of six prescribed medications per day.71 Certain drug classes are particularly implicated. Anticholinergic medications reduce contractility of the smooth muscle of the gut via an antimuscarinic effect at acetylcholine receptor sites, and in some cases (e.g., patients with schizophrenia taking neuroleptics), long-term use may result in chronic megacolon. Anticholinergic medications have been independently associated with daily laxative use in nursing home studies,74 symptomatic constipation in community-dwelling older U.S. veterans,55 and FI in older stroke survivors.75 Although older people are certainly susceptible to the constipating effects of opiate analgesia, a study of nursing home residents with persistent nonmalignant pain showed equivalent constipation rates in chronic opiate users and nonusers over a 6-month period; those taking opiates showed improved function and social engagement.76 Chronic pain is often undertreated in frailer older people, possibly through fear of adverse effects of analgesic drugs, so it is important to note that constipation in this context can be effectively managed by laxative and suppository coprescribing. Transdermal patches (e.g., fentanyl) are associated with lower constipation risk than sustained-release oral morphine.77 All types of iron supplements (sulfate, fumarate, and gluconate) cause constipation in adults, the constipating factor being the amount of elemental iron absorbed.78 Slow-release preparations have a lesser impact on the bowel because they carry the iron past the first part of the duodenum into an area of the gut where elemental iron absorption is poorer. Intravenous iron does not cause constipation and can be an alternative in patients with chronic anemia (e.g., chronic kidney disease) who become constipated on oral iron. Constipation was the main side effect in a 5-year study of calcium supplementation in older women (treatment 13.4% versus placebo 9.1%).79 Calcium supplementation reduced bone turnover and fracture rates in women who took it, but long-term compliance was poor, and constipation may have contributed to this. Calcium channel antagonists impair lower gut motility, particularly in the rectosigmoid.80 Severe constipation has been reported in older patients taking calcium channel antagonists, with nifedipine and verapamil being the most potent inhibitors of gut motility within this class. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) increase the risk of constipation in older people, most likely through prostaglandin inhibition. In a large primary care study, constipation and straining were more prevalent reasons for stopping NSAIDs than was dyspepsia.81 NSAIDs have also been implicated in increasing the risk of fecal impaction82 and stercoral perforation in patients with chronic constipation. Aluminium antacids have been associated with constipation in both nursing home70 and community settings.83 Low consumption of fiber in the form of wheat bran, vegetables, and fruit predisposes toward constipation, and in the United Kingdom, consumption of all of these decreases with advancing age. Community studies of older Europeans who eat a Mediterranean diet rich in fruit, vegetables, and olive oil show lower rates of constipation (4.4% in people aged 50 and older).84 A study of nutritional factors within all the nursing homes in Helsinki found an association between malnutrition and constipation.85 This may be two-way in that marked constipation can cause anorexia, whereas low calorie intake can promote constipation. Constipation is a recognized problem in patients receiving enteral nutrition. A prospective survey of older hospitalized patients receiving nasogastric tube feeding identified constipation as a complication of treatment in 30% of patients.86 Enteric feeding products containing fiber are available, although there are no data on whether constipation is any less of a problem with their use. Low fluid intake in older adults has been related to symptomatic and slow-transit constipation.68,87 Withholding fluids over a 1-week period in young male volunteers significantly reduced stool output.88 Older people are generally at risk of dehydration because of the following factors: • Less effective hormonal responses to hypertonicity • Limited access to drinks because of coexisting physical or cognitive impairments • Voluntary fluid restriction in an attempt to control urinary incontinence Population studies have suggested that alcohol consumption is a preventive factor for constipation symptoms in both men and women.69,73 Over half of diabetic outpatients report constipation symptoms, with neuropathy symptom scores correlating with laxative usage and straining.89 Diabetic autonomic neuropathy can result in slow colonic transit and impairment of the gastrocolic reflex.90 However, one third of diabetic patients with constipation do not have neuropathic symptoms,89 so unrelated reversible factors (e.g., drugs, mobility, fluids) should be considered, particularly in older people. Colonic transit time in frail older people with diabetes and constipation is extremely prolonged at a mean of 200 hours.91 Administering acarbose, an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor with a potential adverse effect of causing diarrhea significantly reduced transit in these patients.91 Diabetes is a risk factor for the development of FI, especially in men.92 FI may occur through mechanisms of93 bacterial overgrowth resulting from prolonged gut transit causing characteristic nocturnal diarrhea and1 multifactorial anorectal dysfunction (reduced basal and squeeze pressures, spontaneous relaxation of the internal anal sphincter, reduced rectal compliance, abnormal rectal sensation).90,94 Acute hyperglycemia can further inhibit anorectal function and colonic peristalsis. It should be noted that a number of oral diabetic medications such acarbose, metformin, thiazolidinediones (e.g., pioglitazone), and the gliptins can cause loose stools (and other gastrointestinal side effects), increasing the risk of FI. Patients with Parkinson disease (PD) suffer from multiple primary pathologies that lead to constipation93: dopaminergic neuron degeneration and increased presence of Lewy bodies in the myenteric plexus, prolonging colonic transit (independent of age, physical activity, medications)1,95; pelvic dyssynergia, causing rectal outlet delay and prolonged straining95; and small increases in intraabdominal pressures on straining. Constipation can become prominent early in the course of the disease, even before motor symptoms develop. In a 24-year longitudinal study, less than one bowel movement a day was associated with a threefold risk of future PD in men.96 Constipation, delayed gastric emptying, and dysphagia are increasingly being recognized as early features of PD that can frequently precede the neurologic manisfestations.97 Fifty-nine percent of PD patients report constipation according to Rome criteria, with 33% being very concerned about their bowel problem.98 Antiparkinsonian drugs may further exacerbate constipation. Pelvic dyssynergia affects 60% of people with PD and may be hard to treat. Botulinum toxin injected into the puborectalis muscle has been used to improve rectal emptying in PD patients with good effect, although repeated injections every 3 months are required to maintain clinical benefit.99 Constipation in patients with PD is often associated with other nonmotor symptoms, all of which may adversely impact quality of life and should be managed symptomatically.100 Dementia predisposes individuals to rectal dysmotility,34 partly through ignoring the urge to defecate. Epidemiologic studies show a significant association between cognitive impairment and nurse-documented constipation in nursing home residents. Patients with non-Alzheimer dementias (PD, Lewy body, vascular dementia), compared with those with Alzheimer dementia, are more likely to suffer from constipation as part of autonomic symptoms.101 Constipation in long-term care residents unable to communicate because of dementia has been linked to physically aggressive behavior102 and development of wandering behavior103 by independent association. Depression, psychological distress, and anxiety are all associated with increased self-reporting of constipation and with FI in older persons. The symptom of constipation can also be a somatic manifestation of psychiatric illness. A careful assessment is required to differentiate subjective complaints from clinical constipation in depressed or anxious patients. Constipation affects 60% of those recovering from stroke on rehabilitation wards,104 and a high number of these have combined rectal outlet delay and slow transit constipation.105 Major FI is Hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia produce neuronal dysfunction that minimizes acetylcholine stimulation of gut smooth muscle and so prolongs transit through the gut. This should especially be looked for and corrected in patients who have acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Hypercalcemia causes conduction delay within the extrinsic and intrinsic gut innervation of the gut neuromuscular bowel dysfunction (which may be reversed following parathyroidectomy). Constipation is not an unusual presenting symptom for clinical hypothyroidism, particularly in older women. Patients on long-term renal hemodialysis have prolonged age-adjusted transit time108; 63% to 72% complain of constipation, with important contributors being diabetes, high (49%) use of resin to prevent hyperkalemia, suppression of the defecation urge while undergoing dialysis, and low fiber intake.109,110 In addition, resin administration can increase the risk of impaction in frail older patients. There is controversy as to whether constipation as a sole symptom should prompt colonoscopy. Following adjustment for age and potential confounders, two or fewer reported bowel movements a week was associated with a greater than twofold risk of colon cancer in a U.S. study, with the association being stronger in women than men; no association was seen with laxatives.111 Another study conducted colonoscopy in 700 patients with constipation and found polyps in 6% (more so in older patients) but no cancer; their conclusion was that colonoscopy for constipation should only be warranted in older people.112 Comparing underlying causes for FI in younger and older men shows colon and prostate cancer to be significantly more common in the older group,113 so the index of suspicion for colorectal cancer should be higher in older adults with bowel symptoms.114 Constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) is a prevalent subtype of IBS that most commonly affects older people, with a preponderance of women.115 Although clinically, IBS-C shares some of the Rome III diagnostic criteria for constipation, it is even more multifactorial, being consistently associated with lower socioeconomic status, anxiety, depression, and somatization.116 It also has a different disease pathophysiology to chronic constipation, so patients respond less well to conventional laxatives and better to newer prokinetic and prosecretory agents. Although available, these newer agents have not been sufficiently tested in older people. A case control study of patients (mean age 68) with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis showed 74% to have prolonged transit.117 Left-sided diverticulosis coli affects 30% to 60% of people older than age 60 in developed countries. High intraluminal pressures while straining at stool in people who have a low fiber diet contributes to the cause of the condition. Uncomplicated diverticular disease may not cause colonic symptoms,118 but symptomatic diverticular disease needs to be correctly diagnosed because the condition shares characteristics with IBS-C of recurrent episodes of abdominal pain and erratic bowel habit with diarrhea sometimes alternating with constipation.116 Distinguishing features are that symptomatic diverticular disease affects an older population and both sexes equally, and patients are likely to have a fever with prolonged episodes of abdominal pain. Physiologic studies suggest that changes in the lower bowel predisposing toward constipation in older people are not primarily age-related. This is compatible with the epidemiology showing that bowel movement frequency alters with aging and that constipation symptoms are more prevalent in older people with comorbidities. Extrinsic causes such as reduced mobility, decreased fluid intake, reduced dietary fiber, comorbidities, and medication impact colonic motility and transit and influence the pathophysiology of constipation. Studies of anorectal function, however, show age-related changes predisposing to FI. Colonic motility depends on the integrity of the central and autonomic nervous systems, gut wall innervation and receptors, circular smooth muscle, and gastrointestinal hormones. Propagating motor complexes in the colon are stimulated by increased intraluminal pressure generated by bulky fecal content. Studies of total gut transit time (passage of radiopaque markers from mouth to anus, normally 80% passed within 5 days), colonic motor activity, and postprandial gastrocolic reflex show no differences between healthy older and younger people.118–120 Conversely, older people with chronic constipation have prolonged transit of up to 9 days.118,121 Transit time can be diagnostically measured by the newer wireless motility capsules technique.122 Markers pass especially slowly through the left colon with striking delay in the rectosigmoid, suggesting that total transit time is prolonged because of segmental dysmotility in the hindgut.123 The prolongation is even greater in institutionalized or bedridden older patients with constipation, with transit time ranging from 6 to more than 14 days.71 Slow transit results in a cycle of worsening constipation by reducing stool water content (normally 75%) and shrinking fecal bulk, which then diminishes intraluminal pressures and hence the generation of propagating motor complexes and propulsive activity. Aging is associated with some intrinsic physiologic mechanisms that may alter colonic function, predisposing older people to this “constipation cycle”124: • Reduced number of neurons in the myenteric plexus and impaired response to direct stimulation,123,125 leading to intrinsic myenteric dysfunction • Progressive loss of interstitial cells of Cajal in the colon124 • Increased collagen deposit in left colon, leading to altered compliance and motility125 • Reduced amplitude of inhibitory junction potentials and hence inhibitory nerve input to circular colonic muscle, causing segmental motor incoordination126 • Increased binding of plasma endorphins to gut receptors in adults older than 60 years127 In normal defecation, colonic activity propels stool into the rectal ampulla, causing distention and reflexic intrinsically mediated relaxation of the smooth muscle of the internal anal sphincter (or anal canal). This is followed promptly by reflex contraction of the external anal sphincter and pelvic floor muscles, which are skeletal muscles innervated by the pudendal nerve. The brain registers a desire to defecate, the external sphincter is voluntarily relaxed, and the rectum is evacuated with assistance from abdominal wall muscle contraction. There is a tendency toward an age-related decline in internal sphincter tone and thickness, particularly beyond the eighth decade.120,128–130 This reduction in internal anal sphincter pressure lowers the threshold for balloon (stimulated stool) expulsion and is much more notable in frail older people with FI.131,132 The clear age-related decline (greater in women than men) in external anal sphincter and pelvic muscle strength128,129 may contribute to both incontinence and evacuation difficulties. Rectal motility appears to be unaffected by healthy aging,120 but an age-related increase in anorectal sensitivity thresholds and reduced rectal compliance have been observed, starting at an earlier age in women than men.133 Patients with dementia and FI tend to exhibit multiple uninhibited rectal contractions in response to rectal distention.131 Younger women with FI are more likely to have isolated anal sphincter defects (often related to child-bearing),134 whereas the anorectal pathology is more multifactorial in older women, including pudendal neuropathy, hemorrhoidectomy, diabetes, and rectal and vaginal prolapse.135 Failure of the anorectal angle to open and excessive perineal descent in older women can also lead to constipation,125 and consequent prolonged straining may compress the pudendal nerve further, exacerbating any preexisting neuropathy. Table 105-5 describes the three main types of anorectal dysfunction that predispose older people to rectal outlet delay. TABLE 105-5 Types of Anorectal Dysfunction Causing Rectal Outlet Delay in Older People Reduced rectal motility and contractions Increased rectal compliance Variable degree of rectal dilation Impaired rectal sensation with blunting of urge to pass stool Over time, increasing rectal distention required to reflexively trigger the defecation mechanism Rectal hard or soft stool retention on digital examination of which patient may be unaware Chronic rectal distention leads to relaxation of the internal sphincter and fecal soiling One postulated cause is diminished parasympathetic outflow as a result of impaired sacral cord function (e.g., from ischemia or spinal stenosis). May also develop through persistent disregard or suppression of the urge to defecate as a result of dementia, depression, immobility, or painful anorectal conditions Paradoxical contraction or failure to relax the pelvic floor and external anal sphincter muscles during defecation Manometric studies show paradoxical increases in anal canal pressure on straining Severe and long-standing symptoms of rectal outlet delay Parkinson disease More common in younger women Increased rectal tone and reduced compliance Lower pain threshold on distending the rectum during anorectal function tests Usually constipation-predominant in older people Rome criteria symptoms: abdominal distention or pain relieved by defecation, passage of mucus, and feeling of incomplete emptying The causes of FI and constipation in older people are usually multifactorial. Comprehensive geriatric assessment (evaluating medical, functional, and psychosocial factors in addition to the bowel) is key to identifying all contributing causes and developing a goal-focused management plan. There is much room for improving standards of bowel assessment in older people in current routine practice; surveys indicate a lack of thoroughness by doctors and nurses in all settings, with failure to obtain an accurate symptom history or to perform rectal examinations.12,15,136 A recent U.K. national audit comparing care in older (65 years and older) and younger patients with FI against National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) standards in primary care, acute hospital, and care home settings showed that bowel history was not documented in 41% older versus 24% younger patients in the hospital and 27% versus 19% in primary care. In older people, there was no documented focused examination in one third of hospital patients, one half of patients in primary care and three quarters of patients in care homes. Overall less than half had documented treatment for an indentified bowel-related cause of FI. FI was frequently attributed to comorbidity. Few patients received copies of the treatment plan, and quality-of-life impact was poorly documented, especially in hospitals. Organizationally it highlighted the fact that assessments of FI in older people were done by geriatricians in only 19% of cases, with low general practitioner involvement also, and concluded that clinicians need to lead on improving care in this area.12,15 It is important for health care providers services and organizations to buy into continence care. Table 105-6 provides an example of a tool (based on U.K. NICE guidance)12,13 that can promote continuous audit with real-time quality improvement in FI management. TABLE 105-6 Example of Continuous Quality Improvement and Audit Tool for Adults with Fecal Incontinence QS Statement 2. Adults reporting or identified as having bowel control problems are offered a full baseline assessment, which is carried out by health care professionals who do not assume that symptoms are caused by any existing conditions or disabilities. Statement 3. Adults with fecal incontinence and their caregivers are offered practical support, advice, and a choice of appropriate products for coping with symptoms during the period of assessment and for as long as they experience episodes of fecal incontinence. Statement 4. Adults with fecal incontinence have an initial management plan that covers any specific conditions causing the incontinence, as well as diet, bowel habit, toilet access, and medication. 3. Percentage of patients with fecal incontinence who have an initial management plan that covers any specific conditions causing the incontinence, as well as diet, bowel habit, toilet access, and medication. Interventions may include addressing specific conditions causing the incontinence and addressing diet, bowel habit, toilet access, and medication needs [adapted from NICE clinical guideline 49 recommendations 1.3.1 to 1.3.15]. Specific conditions that might cause fecal incontinence and require condition-specific interventions include the following: • Rectal prolapse or third-degree hemorrhoids • Acute anal sphincter injury, including obstetric and other trauma

Constipation and Fecal Incontinence in Old Age

Introduction

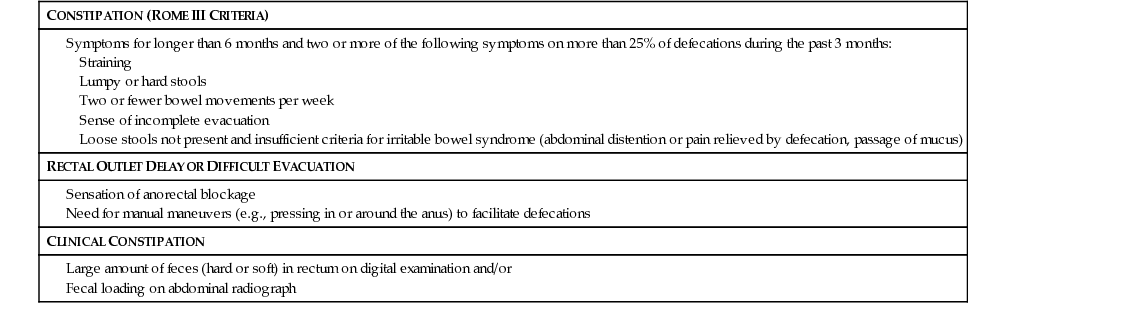

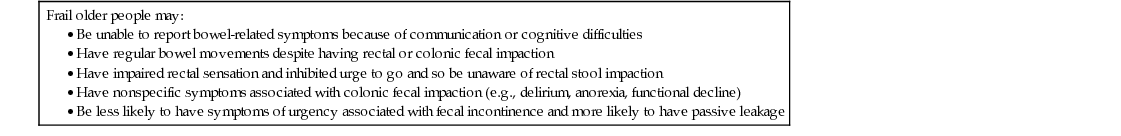

Definitions

CONSTIPATION (ROME III CRITERIA)

RECTAL OUTLET DELAY OR DIFFICULT EVACUATION

CLINICAL CONSTIPATION

Prevalence of Constipation and Constipation-Related Symptoms

Prevalence of Fecal Incontinence in Older People

Risk Factors for Fecal Incontinence and Constipation in Older People

Reduced Mobility

Polypharmacy and Drug Side Effects

Dietary Factors

Diabetes Mellitus

Neurologic Diseases

times more prevalent in stroke survivors than in the nonstroke population.106 FI may develop months after acute stroke and can be transient, consistent with constipation with overflow as one possible cause.75 Epidemiologic data suggest that FI is associated more with disability-related factors (particularly functional difficulties in using the toilet, and anticholinergic medications) than stroke-related factors (e.g., severity and lesion location).75,106,107 Weak abdominal and pelvic muscles following stroke also contribute to problems with evacuation.

times more prevalent in stroke survivors than in the nonstroke population.106 FI may develop months after acute stroke and can be transient, consistent with constipation with overflow as one possible cause.75 Epidemiologic data suggest that FI is associated more with disability-related factors (particularly functional difficulties in using the toilet, and anticholinergic medications) than stroke-related factors (e.g., severity and lesion location).75,106,107 Weak abdominal and pelvic muscles following stroke also contribute to problems with evacuation.

Metabolic Disorders

Colorectal Cancer

Constipation-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Diverticular Disease

Pathophysiology of Constipation and Fecal Incontinence in Older People

Colonic Function

Anorectal Function

Pathophysiology

Clinical Picture

Rectal dysmotility

Pelvic floor dyssynergia

Irritable bowel syndrome

Clinical Evaluation

Goal Name

Improving Fecal Incontinence Care According to NICE Quality Standard 54 and NICE Clinical Guideline 49

Description of indicator

Numerator

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Constipation and Fecal Incontinence in Old Age

105