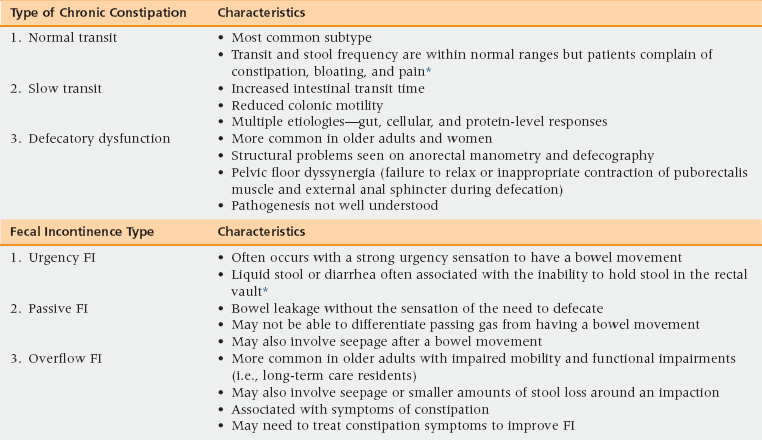

24 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Define the various types of constipation and fecal incontinence (FI), along with associated bowel symptoms. • Recognize subtypes and common conditions that may be associated with constipation and FI. • Describe the clinical evaluation for older adults with constipation and FI, understanding when referral for further evaluation may be needed. • Identify evidence-based nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments for constipation and FI among older adults. Constipation and fecal incontinence (FI) can be classified as functional bowel disorders.1 Functional bowel disorders are usually chronic (more than 3 to 6 months in duration at the time of presentation) and are attributable to the middle and lower gastrointestinal system. Constipation and FI are symptom-based diagnoses that may have multiple etiologies. Often, symptoms of constipation and FI occur simultaneously. Management will be discussed separately for constipation and FI, with a section on fecal impaction that can include symptoms of constipation and FI. Chronic constipation disproportionately affects the elderly, with an estimated 40% of people older than the age of 65 experiencing the condition.2,3 Women have 2 to 3 times more constipation than men. African Americans also exhibit increased risk. Many community-dwelling older adults use over-the-counter preparations, such as stimulant and bulking laxatives. Nearly 85% of physician visits for constipation result in a prescription for laxatives and more than $820 million are spent per year on over-the-counter agents. Few resources are available to health care providers to guide them in an evidence-based approach to this common problem. FI occurs in up to 15% of older women and men.4,5 FI is distressing, socially isolating, and associated with a possible increased risk of dependency in activities of daily living, morbidity, and mortality. Many older individuals with FI do not volunteer the problem to their health care provider, and providers do not routinely enquire about the symptoms. The condition can affect care providers of home-dwelling patients, with FI being cited as a reason for requesting nursing home placement. Because frail, older adults frequently have coexisting urinary symptoms (most often urinary incontinence) and other bowel symptoms (constipation), evaluation and management of other urinary symptoms and FI should be done simultaneously (see Chapter 23).4,6 Even when noted by health care professionals, FI is often managed with absorptive or containment products, especially in the long-term care setting where it is most prevalent. FI can result from constipation with stool impaction and may be more common in certain frail, older populations.7 In a recent study, 81% of residents in long-term care settings had symptoms of constipation and FI.8 However, the true prevalence of impaction and FI in nursing home residents and home-care settings has not been clearly identified. Because constipation with FI is difficult to diagnose, treatments should target constipation. 1. Must include two or more of the following: • Hard or lumpy stool in ≥25% of defecations • Straining during ≥25% of defecations • Sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25% of defecations • Sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage for ≥25% of defecations • Manual maneuvers to facilitate ≥25% of defecations (e.g., digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor) 2. Loose stools are rarely present without use of laxatives Differentiating symptoms of chronic constipation from irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) and diarrhea (IBS-D) may not be as important in older adults, because age ≥50 years is associated with lower rates of IBS.5 However, management can differ between the two diagnoses. IBS-C is defined by recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort for at least 3 days per month in the previous 3 months (onset ≥6 months prior to the diagnosis) that is associated with at least two of the following: 1. Improvement of pain or discomfort upon defecation 2. Onset associated with change in frequency of stool 3. Onset associated with a change in form or appearance of stool The International Continence Society provides a definition of FI that is the “involuntary loss of liquid or solid stool that is a social or hygienic problem.”9 Flatal incontinence may also be a bothersome symptom but is usually excluded from the definition for FI. Other bowel symptoms that may present with FI include rectal urgency, seepage of stool after bowel movements, incomplete evacuation, and loss of stool without any sensory awareness. Constipation and FI can be subgrouped as primary (subtypes of constipation or FI) or secondary (e.g., caused by a diagnosed medical condition or use of medications). Primary types of constipation are more clearly defined and are associated with specific diagnosis codes. The primary types of FI are more open to interpretation and are not associated with specific diagnosis codes. The primary types for constipation and FI are listed in Table 24-1 with secondary causes listed in Box 24-1. TABLE 24-1 Primary Pathophysiologic Types of Chronic Constipation and Fecal Incontinence *Presence of pain increases the likelihood of a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) or diarrhea (IBS-D). Diarrhea-inducing medications include those that decrease transit time and cause loose stool consistency. Medications that induce diarrhea may be time-limited (i.e., a side effect that improves with time or with limited use of the medication); they may change intestinal bacterial flora, or the resulting diarrhea may be the result of a higher than normal serum concentration of the medication. Medications with associated time-limited diarrhea include metformin, high doses of proton pump inhibitors, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, colchicine, and chemotherapeutic agents. Antibiotics may also cause loose stools and diarrhea by changing intestinal bacterial flora. Toxic levels of some drugs, such as digoxin, can cause loose stools. Nonprescription medications that cause loose stools include laxatives and some NSAIDS. Tube feedings may also be associated with loose stool. Physical examination should include a rectal exam; palpating for hard stool; and assessing for masses, anal fissures, sphincter tone, prostatic hypertrophy in men, hemorrhoids, push effort during attempted defecation, and posterior vaginal masses in women. Laboratory testing should include a complete blood count, serum calcium, thyroid function tests, and fecal occult blood testing. Evaluation for causes of loose stool should look for infection (including Clostridium difficile evaluation, fat malabsorption, and the presence of leukocytes). Other testing could involve serum tests to evaluate for celiac disease.

Constipation and fecal incontinence

Prevalence, impact, and definitions

Symptoms and definitions

Primary and secondary causes of constipation and fecal incontinence

History and physical examination

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Constipation and fecal incontinence