The very first issue of this series, from 1987, reviewed the state of knowledge about what was then called Histiocytosis X. At that time, the most important advances involved the understanding that a single cell type, one which resembled a mature Langerhans cell, was present in the myriad forms of the disease. Although the disease could now be called LCH, its fundamental nature remained a puzzle. Eleven years later, another issue in this series, edited by Maarten Egeler and Giulio D’Angio, provided an update that was remarkable for integrating the new finding that the cells in LCH are clonal, suggesting that LCH might be a neoplasm. However, a mechanistic understanding of its pathogenesis was still unavailable. The current issue is focused on a series of recent advances that begin to reveal the true nature of LCH and provide some therapeutic targets. In particular:

- 1.

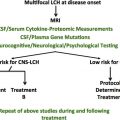

Recurrent genomic abnormalities. Dr Rollins and Drs Picarsic and Jaffe discuss the new understanding of LCH as a neoplastic disease based on the presence of somatic mutations in components of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in the majority of patients. Drs Monsereenusorn and Rodriguez-Galindo discuss current treatment as well as the implications of these actionable mutations in the future treatment of LCH.

- 2.

Cell of origin. Drs Collin, Bigley, McClain, and Allen discuss recent findings indicating that LCH is most likely a neoplasm of myeloid progenitors rather than Langerhans cells and the implications this has for treatment and diagnosis.

- 3.

Clinical treatment. Drs Monsereenusorn and Rodriguez-Galindo present an up-to-date summary of the standard and experimental approaches to LCH treatment, and our late colleague, Dr Bob Arceci, and his coauthor, Dr Imashuku, describe the state of knowledge about neurodegeneration in LCH, a devastating concomitant in many cases.

The previously mentioned 1998 issue of Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America included articles on the relatively newly described entity of HLH. At that time, HLH was a clinical syndrome that had been identified as a primary hereditary disease in infants and young children, and as an acquired disease associated with infection, autoimmune disease, and malignancy. At that time, the pathophysiologic basis for the disease was unknown. The intervening years have witnessed an explosion of information about the natural history of the disease and its molecular underpinnings. In this issue of the Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America , we include a series of reviews summarizing the state of our knowledge of HLH. These reflect the growing awareness of the unexpectedly common occurrence of this disorder in older age groups, as well as our current understanding of the molecular basis for familial HLH and its relationship to the acquired forms seen in patients of all ages:

- 1.

Pathogenesis of HLH. Drs Filipovich and Chandrakasan discuss the pathophysiology of HLH with regard to the immune pathways that are dysregulated in the disease. They discuss the identified molecular lesions that underlie the familial form of the disease, and also the increasing understanding of the role of molecular defects in acquired forms of HLH.

- 2.

Familial HLH. Dr Degar discusses the pathophysiologic and clinical features of HLH as seen in young children. She presents the current approach to diagnosis and treatment of the disease as seen in the pediatric age group.

- 3.

HLH in adults. Drs Campo and Berliner present the features of the increasingly recognized syndrome of HLH as seen in adult patients, emphasizing the role of hypomorphic alleles of familial HLH genes in its pathogenesis, the frequent association with lymphoproliferative malignancy, and the necessity of early intervention in this otherwise rapidly fatal syndrome.

- 4.

Macrophage activation syndrome. Drs Ravelli, Davì, Minoia, Martini, and Cron discuss the features of HLH as seen in association with systemic autoimmune diseases, especially systemic lupus erythematosis and juvenile inflammatory arthritis. They emphasize the distinctly different natural history, prognosis, and treatment approaches to this variant of HLH in comparison to the other acquired forms of the disease.

- 5.

Stem cell transplant for HLH. Stem cell transplant is the only curative approach to familial HLH and may represent the best option for many patients with the acquired form of the disease as well. Dr Nikiforow details the clinical approach to transplantation across the spectrum of HLH patients, including considerations of donor choice, preparative regimens, and timing of transplant to optimize outcomes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree