1. Elucidation of parameters other than age that define the AYA patient

2. Development of and participation in clinical trials benefiting AYA patients

3. Specialization of health services delivery

4. Focus on oncofertility

5. Professional training in AYA oncology

6. Addressing the economic costs of cancer care

7. Expanding access to health-care and health insurance coverage

8. Application of developmental behavior therapy to understanding the experience of cancer in young adulthood

9. Improving adherence of AYAs to cancer treatment and diagnostic studies

10. Support and utilization of the peer advocacy community

- 1.

Elucidation of parameters other than age that define the AYA patient. In a broad sense, these require greater understanding of the biology of cancers and their AYA hosts. The former will yield to powerful technologies such as next-generation sequencing studies, as described by Pui and colleagues with respect to ALL [2]. The focus on host biology must surely be the physiological trajectory from childhood to adult life and how the inherent changes impact cancer and its treatment. Specimens of tumor and normal tissue from AYAs are more underrepresented in biorepositories than for any other age group.

- 2.

Development of and participation in clinical trials benefiting AYA patients. Collaborative initiatives involving pediatric and medical oncologists are beginning to bear fruit with respect to trial design, including changing limits on age eligibility, that are facilitating the availability of trials to AYAs with cancer. A nut that is proving at least as hard to crack is increasing the accrual of AYAs to these opportunities. There are many pitfalls on the pathway to enrollment [3] requiring multiple tactics to effect improvement, as exemplified by successes in the United Kingdom [4] and the United States [5].

- 3.

Specialization of health services delivery. It has become a mantra in the AYA cancer community that programs, including physical facilities, designed to meet the specific needs of AYA patients (Fig. 35.1) will result in better outcomes. The jury has been sequestered but the verdict not yet given, for the evidence has not been subject to the requisite rigorous analyses. These must range from patient-reported outcomes to formal economic evaluation. Moreover, assessments must encompass a spectrum of elements including locus of care, transitions [6], long-term follow up, and future health and well-being. In view of the considerable commitments, not least pecuniary, to mushrooming AYA programs, in-depth assessment of their value must be a high priority.

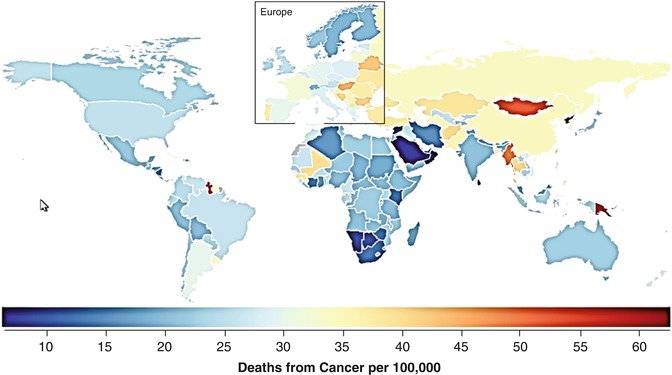

Fig. 35.1

Average cancer death rate during 2013 in 15- to 49-year-olds in 188 countries (Modified from Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) [36])

- 4.

Focus on oncofertility. If there is one issue that is peculiarly apposite for AYA oncology, this is surely it. Emblematic of the reproductive age span, the AYA population has a dominant interest in the preservation of their fertility. Responding to that need, Teresa Woodruff (who coined the term oncofertility [7]) and her colleagues formed the Oncofertility Consortium in 2006. As stated on their website https://oncofertility.northwestern.edu, “The Oncofertility Consortium is a national interdisciplinary initiative designed to explore the reproductive future of cancer survivors.” This has provided a stimulus for others. In Canada the Cancer Knowledge Network launched the Oncofertility Referral Network in 2014 and is working in collaboration with the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society to develop a national database that will provide performance metrics in this important area.

- 5.

Professional training in AYA oncology. A stated priority of the standards committee of LIVESTRONG is to foster the development of educational programs, leading to formal certification, in AYA oncology for a wide spectrum of health-care professionals. Independently, initiatives in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada have risen to the challenge. In the United Kingdom, the University of Coventry offers three modules of e-learning, available to all health-care professionals, leading to a postgraduate certificate in teenage and young adult cancer care (http://www.coventry.ac.uk). A similar two semester course is offered by the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, Australia, that provides a graduate certificate of adolescent health and well-being oncology stream (http://www.rch.org.au). As indicated in the Introduction, the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada has acknowledged adolescent and young adult oncology as an area of focused competence with a full-time 1-year program for physicians that leads to a diploma in this subject. Additionally, the American Society of Clinical Oncology has 11 current online modules on AYA oncology available at http://university.asco.org/focus-under-forty.

- 6.

The economic cost of medical care is a greater burden on AYAs than on any other age group. In general, they have the least economic resources and, among cancer survivors, the greatest financial hardship [8]. This issue has become all the more acute with the dramatic increase in the cost of cancer drugs that has affected both parenteral and oral medications [9, 10]. In the United States, the most common cause of personal bankruptcy is medical expenditure [11], and a large group of prominent oncologists worldwide has published a request for government regulation on cancer drug costs [12].

- 7.

The role of health insurance for AYAs has also become all the more acute, especially since delays in and suboptimal medical care lead to more advanced stages of cancer in AYAs [13–15]. Since the first edition of this book, the United States made health insurance available to most 18- to 25-year-olds via their parents’ health insurance policies. An estimated 4,000 AYAs were diagnosed with cancer during the first 15 months after insurance companies in the United States were required to cover, up to the age of 26, patients who would otherwise not have been insured [16]. The lack of health insurance for AYAs is more problematic in the United States than elsewhere but underlies the socioeconomic differences in cancer survival outcomes and prevention described in this book.

- 8.

Application of developmental behavior therapy to understanding the experience of cancer in young adulthood. The high prevalence and likely underestimation of psychological distress in AYA survivors of cancer is well described [17]. Regrettably this is related in part to unsatisfied needs for psychological support. This is particularly problematic in the age group 20–29 years [18], defining a population for whom services are especially necessary. The contributions of peer support programs have been important in reducing this deficit, as have the numerous social media targeting the AYA cancer survivor community. Nevertheless, high proportions of these young people report distress, compounded by unmet needs for information, counseling, and practical support. Developing a valid tool for the detection of psychological distress in this population remains in itself an unmet need [19].

- 9.

A specific need is to improve adherence to treatment and diagnostic evaluation. AYAs are the age group that has the least compliance with oral medication and, in the United States at least, the least health insurance to cover the costs of clinical, hospital, and drug costs. In AYAs with leukemia, decreased adherence to oral medications has been associated with lower disease-free survival rates [20, 21]. In adolescents with ALL, only one-third of blood samples showed concentrations of the 6-mercaptopurine active metabolite within the therapeutic reference range [22]. Nonadherence to oral 6-mercaptopurine has been found to increase at an odds ratio of 1.07 per year of age [23]. Young adults with chronic myeloid leukemia, for whom oral therapy with BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors is critical, have been shown to have a lower adherence than older adults [24].

- 10.

Support and utilization of the peer advocacy community. The field of AYA oncology has been advanced considerably as a result of the highly effective national initiatives undertaken by communities of advocates and support groups. These have been especially well developed in Australia [25], the United Kingdom [26], and the United States [27]. Particularly notable contributions have been made by LIVESTRONG in the United States that include position statements on quality of care [28] and the training of health professionals [29]. It is anticipated that more initiatives of this sort will be forthcoming. Moreover, as these entities work increasingly and synergistically with organizations of health-care professionals, the pace of progress in AYA oncology will only accelerate, to the benefit of young people with cancer at large.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree