John C. Watkinson and David M. Scott-Coombes (eds.)Tips and Tricks in Endocrine Surgery201410.1007/978-1-4471-2146-6_22

© Springer-Verlag London 2014

22. Complications in Thyroid Surgery and How to Avoid Them

(1)

Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, 243 Charles St., Boston, MA 02114, USA

Abstract

Although the current incidence of complications of thyroid surgery in good hands is acceptably low, the impact of complications can be significant

Complications in Thyroid Surgery and How to Avoid Them

Although the current incidence of complications of thyroid surgery in good hands is acceptably low, the impact of complications can be significant.

Literature clearly shows a direct correlation between experience and rate of complications, a finding that supports a dedicated subspecialty training.

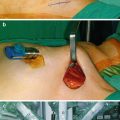

Hematoma

Incidence is low (0–3 %).

Typically results from venous bleeding from small veins.

Usually presents during the initial 4–8 h postoperative period but may have a delayed presentation up to several days, which makes it challenging to make an evidence-based recommendation regarding length of “safe” hospital stay.

Current literature shows no significant value of placing drains after thyroid surgery, and pressure dressing does not seem to prevent hematoma formation.

Venous pressure can be reduced during and after surgery by obtaining reverse Trendelenburg position (head and back up).

At the conclusion of the procedure and prior to closure, a final check for hemostasis should be confirmed by asking the anesthetist to perform a Valsalva maneuver which increases the venous pressure. This should be performed with a careful reinspection of the operative field.

Acceptable means of controlling vessels include appropriate application of ligatures, clips, bipolar diathermy, and other energy technologies such as the harmonic scalpel.

Additional use of hemostatic agents (e.g., Surgicel) at the thyroid bed may be helpful but should never be a substitute for strict hemostasis.

When encountered, a hematoma should urgently be addressed by early securing of the airway (ideally by intubation), securing of hemostasis, and evacuation of the hematoma.

A small nonprogressive hematoma can be expectantly managed.

A large and progressive hematoma carries a major risk of airway obstruction that results from blood accumulating in a closed space leading to ecchymotic submucosal laryngeal edema. This process could result in a progressive airway narrowing which makes intubation potentially difficult if not performed on a timely fashion. Prompt attention to the airway, preferably by means of endotracheal intubation, with concurrent evacuation of hematoma and achievement of hemostasis should be performed.

Postoperative care should be optimized to avoid nausea, vomiting, and coughing.

Instructions should be given to nurses in order to alert the physician about any concerns of neck swelling or breathing or swallowing difficulties.

Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve (RLN) Injury

Incidence of RLN injury varies and may be small in expert hands. However, rates of immediate RLN paralysis after surgery are likely in the order of 5–10 % in the general community.

Preoperative Considerations

A detailed knowledge of RLN anatomy is essential.

Pre- and postoperative voice does not correlate well with the actual status of RLN. Therefore, pre- and postoperative direct laryngeal exam should routinely be employed on all thyroid patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree