Antonia Kolokythas (ed.)Lip Cancer2014Treatment and Reconstruction10.1007/978-3-642-38180-5_13

© Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014

13. Complications Associated with Radiotherapy

(1)

Department of Radiation Oncology, The University of Chicago and The University of Illinois at Chicago, 900 E. 57th Street, KCBD Room 6142, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Abstract

As discussed elsewhere in this textbook, radiotherapy has numerous applications in the treatment of lip cancers. However, there are also numerous toxicities associated with the use of radiotherapy in this setting. There are few series evaluating the toxicities incurred specifically by patients with lip cancer treated with radiotherapy, but many of the toxicities incurred by patients treated for lip cancer are similar to those incurred during treatment for other head and neck malignancies. In this chapter, we will discuss the common acute and late toxicities associated with lip cancer radiotherapy, as well as the general management approaches to both prevent and control the severity of these toxicities.

13.1 Introduction

As discussed elsewhere in this textbook, radiotherapy has numerous applications in the treatment of lip cancers. However, there are also numerous toxicities associated with the use of radiotherapy in this setting. There are few series evaluating the toxicities incurred specifically by patients with lip cancer treated with radiotherapy [3, 8, 16, 21–23], but many of the toxicities incurred by patients treated for lip cancer are similar to those incurred during treatment for other head and neck malignancies. In this chapter, we will discuss the common acute and late toxicities associated with lip cancer radiotherapy, as well as the general management approaches to both prevent and control the severity of these toxicities.

There are several factors that predispose patients with lip cancer to having toxicity with radiotherapy. In general, patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy have a higher risk and severity of toxicity, and thus these patients must be monitored closely for reactions to radiation [1]. Additionally, patients treated with accelerated or hyperfractionated radiation schedules may be at increased risk for toxicity [19]. Radiation in a previously irradiated field also increases the risk of toxicity [40]. There are also genetic syndromes and comorbid conditions that increase the risk of toxicity with radiotherapy, such as ataxia-telangiectasia and collagen vascular disorders [34, 47]. These factors may increase the risk of toxicity in a patient receiving radiation therapy and thus make patient selection and careful monitoring important.

The toxicities due to radiation therapy are intimately related to the size of the treatment field, the radiation dose, and the organs that fall within the irradiated field. Anatomic areas/organs receiving high radiation doses are at higher risk for developing toxicity compared to those receiving lower doses, while areas receiving dose only due to scatter are at minimal risk for toxicity [5, 30]. The areas in proximity to the treated lip(s) are more likely to receive higher doses, and thus, patients more commonly develop toxicities related to these regions [3, 16, 21–23]. Below, we will review the specific normal tissues at risk and the related acute and late toxicities.

13.2 Acute Toxicities

The acute toxicities of head and neck radiotherapy often begin in the second or third week of treatment and tend to appear insidiously. Once these toxicities develop, they may worsen over the course of treatment and usually reach maximum severity near the end of treatment or several days after completion of treatment. Patients usually notice improvement in the severity of symptoms 1–2 weeks after completion of radiotherapy, and most patients have gradual improvement over subsequent weeks. It is vital for the multidisciplinary team to be watchful of any unexpected or abnormally severe acute toxicity, as this warrants investigation to make sure that the radiation plan and actual dose of radiation delivered are truly as intended.

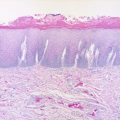

13.2.1 Radiation Dermatitis

Most patients receiving radiotherapy for lip cancer have some degree of radiation dermatitis [21]. Radiation dermatitis usually manifests 10–14 days after beginning radiation and is unlikely below doses of approximately 20 Gy [24, 26]. Early and mild radiation dermatitis presents as erythema of the skin and can progress around the fourth to fifth week to brisk erythema and/or dry and moist desquamation. Moist desquamation is more common as doses increase past 40 Gy and is characterized by bullae formation and exudative discharge [33]. Following completion of radiotherapy, the dermatitis usually resolves over the next 1–3 months.

During treatment, erythema and dry desquamation are commonly treated with moisturizing agents such as Radiaplex© or Aquaphor©. Moist desquamation is commonly treated with domeboro soaks©. It is imperative to monitor for superinfection of any moist desquamation lesions while patients undergo therapy.

13.2.2 Xerostomia

Radiotherapy also results in damage to salivary glands. Although the exact mechanism in humans is unclear, it may be due to acinar cell apoptosis or disruption of cell membranes [45]. Regardless of the mechanism, irradiation of salivary gland tissue results in decreased salivation and altered composition of saliva [4]. These changes can begin shortly after beginning radiotherapy and can have a large impact on patients’ quality of life [28]. Patients commonly describe xerostomia and thickened oral secretions during the treatment course. Depending on the volume of the salivary gland(s) irradiated and the dose received, this may improve upon completion of radiotherapy to some degree, but many patients continue to have persistent xerostomia years after completion of radiotherapy [18, 28].

13.2.3 Taste

Depending on the extent of the oral cavity that is irradiated, patients may describe dysgeusia or ageusia. This is due to a combination of alteration in saliva and direct damage to taste buds [45]. It usually begins early on in treatment and gradually improves following completion of radiotherapy. Usually, patients regain much of their original taste 1 year after completing radiotherapy; however, it can take up to 5 years for this to occur, and there may be some foods or drinks that taste slightly different even at this point.

13.2.4 Mucositis

Most patients receiving radiotherapy to the lip will develop some degree of mucositis in the anterior oral cavity. The mechanism behind the acute oral mucositis observed in patients receiving radiotherapy is likely related to epithelial cell mitotic death [43]. This results in an acute inflammatory response causing damage to the mucosa. Bacterial or fungal superinfection may also play a role. The extent of the irradiated field and radiation dose may determine the amount of tissue that becomes inflamed and the severity of the symptoms. This can make eating food and drinking liquids very painful for patients. Thus, they should be counseled to switch to softer foods and nutritional supplements as necessary to ensure adequate nutritional uptake, as maintaining this can be difficult. Additionally, pain should be aggressively treated with narcotic pain medications as necessary. If patients develop dehydration, IV hydration should be employed to maintain fluid balance, and electrolytes should be checked regularly.

13.2.5 Weight Loss

Many patients suffer weight loss while undergoing radiotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer. Even prior to beginning treatment, patients may have lost weight due to pain with intake of food, physical obstruction, or malignancy-induced cachexia [14]. Additionally, patients may have significant amounts of weight loss over the course of treatment due to a combination of the above-acute reactions to radiotherapy. Weight loss of greater than 20 % of prediagnosis weight has been associated with higher rates of treatment interruption, infection, hospital readmission, and mortality [6]. Thus, it is crucial to limit the weight lost by patients receiving radiotherapy to the head and neck region.

In early lip cancer, the fields involved are not as extensive as in advanced disease, and thus, the risk for significant weight loss is likely lower for patients with smaller tumors. However, clinicians should be vigilant for excessive weight loss in patients receiving radiotherapy and, particularly, those treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy or with larger tumors as they are at higher risk of suffering more significant complications and weight loss [27].

For patients with significant weight loss or at high risk for development over the course of treatment, the help of a nutritionist or dietician can be valuable in tailoring diet modifications to maximize caloric intake and for optimal nutritional supplementation [2]. Early nutritional intervention may help to limit weight loss over the course of treatment [25, 39]. Additionally, clinicians should use nonnarcotic and narcotic agents to try to control odynophagia and pain from mucositis.

Patients with persistent weight loss despite the above interventions may need placement of an enteral feeding tube (either nasogastric or gastrostomy tube) for nutritional support [27]. The optimal timing (or severity of weight loss) of placement of an enteral feeding tube is controversial. Some advocate prophylactic enteral feeding tube placement in patients with advanced head and neck cancer or very high risk of weight loss [41, 44], while most others use a reactive approach based on percent of weight loss [11, 13]. The placement of gastrostomy tubes is associated with the possibility of complications and may even increase the risk for late esophageal toxicity [11, 13]. Thus, the risks and benefits must be considered carefully prior to such intervention.

13.3 Late Toxicities

The late toxicities associated with radiotherapy to the head and neck region usually begin to present 3–6 months after completion of radiotherapy, and patients are at risk for late toxicity even decades after completion of treatment. Additionally, acute toxicities developed during treatment such as severe mucositis or xerostomia may not resolve and could become long-term issues in some patients. Similar to the acute toxicities, the long-term changes due to radiotherapy are limited to the regions treated, and thus, larger fields place a larger area at risk. For most patients with lip cancer, the two most significant late toxicities are cosmetic changes and functional changes in the irradiated area.

13.3.1 Motor and Sensory Dysfunction

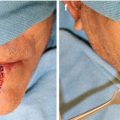

For most patients with early lip cancer, lip dysfunction, although possible, is rare after radiotherapy [8, 22]. When present, sensory dysfunction could present as decreased or absent sensation or conversely increased sensitivity of the lip. Issues with motor function could result in oral incontinence or trismus. Gooris et al. found that in 51 patients receiving definitive external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), 4 had abnormal motor function and 8 had altered sensation [22]. Ghadjar et al. evaluated 103 patients undergoing high-dose-rate (HDR) or low-dose-rate (LDR) brachytherapy and found that five patients developed lip dysfunction and 11 had alteration in sensitivity of the lip [21].

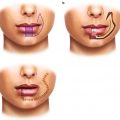

13.3.2 Cosmetic

Patients treated with primary radiotherapy for lip cancer generally have excellent long-term cosmetic outcomes [3]. Issues that may arise include skin atrophy, hypo-/hyperpigmentation, dryness, or, in more severe cases, ulceration. Most patients have minimal to mild skin changes in the lip following radiotherapy, and few patients have severe skin changes [8, 22]. Gooris et al. found that of 51 patients receiving primary EBRT, one developed telangiectasia, 4 developed atrophy, and 2 developed fibrosis, most of which were mild in nature [22]. However, 90 % of patients were satisfied with their cosmetic outcome. Published series of patients treated with brachytherapy suggest that those treated with that modality may similarly have excellent cosmetic results [16, 23]. The risk of cosmetic changes may be higher in patients who undergo surgery prior to radiotherapy [8, 22]. Additionally, those requiring larger fields due to advanced disease may have a higher risk for more severe cosmetic changes.

13.3.3 Other Late Toxicities

Patients with locally advanced tumors or large radiation fields are at risk for many other potential late toxicities depending on the normal tissue structures involved and the doses to these regions. If the relevant organs are in the field, patients may be at risk for fistula, xerostomia, increased risk of dental caries, persistent need for enteral feeding, esophageal stricture, osteoradionecrosis, brachial plexopathy, hypothyroidism, and accelerated carotid atherosclerosis [12, 15, 20, 27, 29, 35–37, 42, 46].

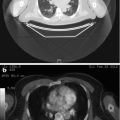

13.4 Prevention of Toxicity

Radiation oncologists have attempted to find ways to limit the toxicity from radiotherapy in the treatment of head and neck cancers. As discussed above, the toxicity profile is at least partly dependent upon the organs and structures irradiated and the doses they receive. Dose limits for normal organs and structures have been suggested by several different authors, with the goal to minimize the toxicity patients experience from their radiation treatments [5, 7, 31, 32, 38]. These limits are used during the development of radiation plans. If on first iteration a plan does not satisfy these constraints, it may be changed until it does. Additionally, the use of intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) may allow for better sparing of critical organs from high doses of radiotherapy and more sculpted dose profiles [10, 17]. Furthermore, image-guided radiotherapy using kilovoltage imaging and cone beam CT imaging can permit smaller treatment margins, thereby decreasing doses to surrounding structures [9].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree