J.D. is a 76-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer. She was diagnosed a little over 3 years ago with a 2.3 cm poorly differentiated infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the upper outer quadrant of the right breast. She elected to undergo a lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy. The tumor was estrogen and progesterone receptor-negative (ER/PR−) and HER-2/neu negative, the sentinel lymph node was negative, and there was some lymphovascular space invasion. She met with a medical oncologist who strongly recommended that she receive chemotherapy. The potential side effects of chemotherapy frightened her, and several months of chemotherapy would definitely interfere with her plans to cruise the Mediterranean with her newly retired husband. Her husband had worked very hard running the family business all the years that they had been married, and had promised to hand the business over to their children when he turned 75. The cruise was a fortieth wedding anniversary trip, and she was looking forward to finally spending some quality time with her husband. She declined any adjuvant therapy other than radiation and even compromised with her radiation oncologist to receive a shortened course of therapy with slightly larger doses of radiation each day, which was still an accepted course of treatment. She took a variety of “natural” remedies recommended by friends and family, which she used to maintain her general good health and boost her immune system. On her 3-year follow-up visit, her radiation oncologist appreciated a mass in the right axilla. A biopsy confirmed the presence of an ER/PR− infiltrating ductal carcinoma in an axillary lymph node. J.D. was told she needed surgery and chemotherapy or she would soon die of her breast cancer. Her feeling about the matter was that the recommended therapies would incapacitate her and she would much rather spend the time that she had left enjoying her 6-month-old and 2-year-old grandchildren. She presented to an integrative physician requesting alternative therapies for her recurrent breast cancer.

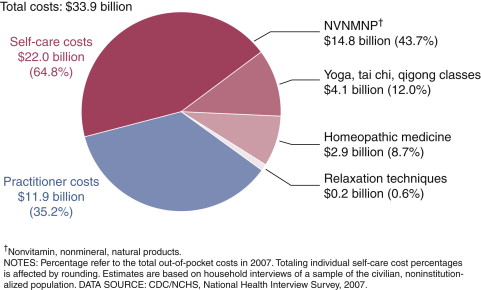

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among the general population has grown tremendously in the last couple of decades. Eisenberg’s initial report in 1993 and follow-up survey in 1997 shed light upon the number of American patients who sought out “unconventional care” (defined as therapies neither taught widely in medical schools nor generally available in most hospitals). Those survey results revealed that in 1990, one in three patients (34%) reported using an unconventional therapy in the previous year, and by 1997, that number had increased to 42%, resulting in an estimated 629 million visits to CAM providers, which exceeded the number of visits to all U.S. primary care physicians during the same time period. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, Americans spent a staggering $33.9 billion out of pocket on CAM visits and products in 2007. ( Figure 21-1 .)

This chapter reviews the incidence of CAM use among cancer patients, the pitfalls that may be associated with its use, and the evidence to support certain therapies during cancer treatment.

Why Doctors Need to Ask

Primary care physicians and oncologists are very likely to have cancer patients using complementary therapies either during their active treatment or as survivors. A survey of 453 outpatients seen in the MD Anderson Cancer Center clinics between December 1997 and June 1998 showed that 83.3% had used some form of CAM. A recent review of the literature revealed that between 64% and 81% of cancer survivors use vitamin or mineral supplements. Gansler et al. examined the use of “complementary methods” in survivors of ten different cancer types using data from the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors-I (SCS-I). Among these 4139 cancer survivors the most commonly used therapies were as follows: prayer/spiritual practice (61%), relaxation (44%), faith/spiritual healing (42%), nutritional supplements/vitamins (40%), meditation (15%), religious counseling (11%), massage (11%), and support groups (10%).

Because women are more likely to use CAM, it is not surprising that among cancer patients, breast or ovarian cancer survivors are the most likely to use complementary therapies. Between 63% and 83% of breast cancer patients use some form of complementary therapy. The reasons patients give for trying CAM therapies are listed in Table 21-1 .

| Richardson (cancer patients) |

|

| Barnes (all patients) |

|

| Astin (all patients) |

|

| Verhoef (cancer patients) |

|

In spite of the high proportion of patients using CAM, only a minority of them discuss it with their physicians. According to the Eisenberg surveys, 72% of patients who were using CAM did not discuss it with their physicians. A review of the literature revealed that between 31% and 68% of cancer patients do not discuss their supplement use with their physicians. There are clearly barriers to communication between patients and their physicians regarding CAM therapies. Interviews with cancer patients have revealed three common themes describing these barriers: physicians’ indifference or opposition to CAM use, physicians’ emphasis on scientific evidence, and patients’ anticipation of a negative response from their physician.

Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative: What’s in a Name?

There is an important distinction to make between “complementary” and “alternative” medicine. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines “complementary” therapies as those that are used in addition to conventional therapies and “alternative” therapies as those that are used instead of conventional therapies. The major categories of CAM therapies as defined by NCCAM are given in Table 21-2 .

| Whole Medical Systems | Whole medical systems are built upon complete systems of theory and practice. Often, these systems have evolved apart from and earlier than the conventional medical approach used in the United States. Examples of whole medical systems that have developed in Western cultures include homeopathic medicine and naturopathic medicine. Examples of systems that have developed in non-Western cultures include traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda. |

| Mind-Body Medicine | Mind-body medicine uses a variety of techniques designed to enhance the mind’s capacity to affect bodily function and symptoms. Some techniques that were considered CAM in the past have become mainstream (for example, patient support groups and cognitive-behavioral therapy). Other mind-body techniques are still considered CAM, including meditation, prayer, mental healing, and therapies that use creative outlets such as art, music, or dance. |

| Biologically Based Practices | Biologically based practices in CAM use substances found in nature, such as herbs, foods, and vitamins. Some examples include dietary supplements, herbal products, and the use of other so-called natural but as yet scientifically unproven therapies (for example, using shark cartilage to treat cancer). |

| Manipulative and Body-Based Practices | Manipulative and body-based practices in CAM are based on manipulation and/or movement of one or more parts of the body. Some examples include chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation and massage. |

| Energy Medicine | Energy therapies involve the use of energy fields. They are of two types:

|

The term “integrative medicine” applies to a practice that incorporates evidence-based complementary therapies with conventional care; considers patients’ beliefs about health, illness, and treatment when making recommendations; and empowers patients to participate in their health care decision-making process.

One of the reasons physicians give for being reticent to use or recommend CAM is the paucity of well-conducted clinical trials involving CAM therapies. NCCAM is the branch of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) responsible for conducting research into CAM therapies and disseminating reliable information on CAM to the public. NCCAM started out in 1991 as the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) and its budget has grown from an initial $2 million to $128.8 million in 2010. Over $295 million was spent on CAM research at the NIH in 2009. This,

J.D. met with an integrative physician and explained her reservations about receiving conventional care for the axillary recurrence of her breast cancer. She felt guilty about not taking the medical oncologist’s advice but did not feel that he had listened to her concerns about therapy. She was anxious, depressed, and not sleeping. She was looking for a natural way to treat her cancer that she could control and which wouldn’t have side effects that could interrupt her time with her grandchildren. After all, if she got chemotherapy now, she wouldn’t be allowed to be around her grandchildren. Her niece had already recommended several supplements and dietary changes that she read about online and, although J.D. was heeding her niece’s advice, she had doubts about the effectiveness of these interventions and her ability to continue to afford them. She also had noticed that the mass under her arm had gotten a little larger and was beginning to hurt. The integrative physician reviewed J.D.’s regimen with her including the evidence (or lack of evidence) to support each supplement’s use. Ultimately, they decided that she would incorporate more soy, fruits, and vegetables in her diet; go for a 30 minute walk with her husband every day; and attend yoga and guided imagery classes at the cancer center. Her concerns and misconceptions about surgery and chemotherapy were addressed, as well as the impact these treatments would have on the time she spends with her family. She agreed to the surgery, and was encouraged to use acupuncture to manage the postoperative nausea that had been so debilitating after her first surgery.

J.D. met with an integrative physician and explained her reservations about receiving conventional care for the axillary recurrence of her breast cancer. She felt guilty about not taking the medical oncologist’s advice but did not feel that he had listened to her concerns about therapy. She was anxious, depressed, and not sleeping. She was looking for a natural way to treat her cancer that she could control and which wouldn’t have side effects that could interrupt her time with her grandchildren. After all, if she got chemotherapy now, she wouldn’t be allowed to be around her grandchildren. Her niece had already recommended several supplements and dietary changes that she read about online and, although J.D. was heeding her niece’s advice, she had doubts about the effectiveness of these interventions and her ability to continue to afford them. She also had noticed that the mass under her arm had gotten a little larger and was beginning to hurt. The integrative physician reviewed J.D.’s regimen with her including the evidence (or lack of evidence) to support each supplement’s use. Ultimately, they decided that she would incorporate more soy, fruits, and vegetables in her diet; go for a 30 minute walk with her husband every day; and attend yoga and guided imagery classes at the cancer center. Her concerns and misconceptions about surgery and chemotherapy were addressed, as well as the impact these treatments would have on the time she spends with her family. She agreed to the surgery, and was encouraged to use acupuncture to manage the postoperative nausea that had been so debilitating after her first surgery.

however, pales in comparison to the amount spent on biomedical research, which, in 2003, was an estimated $94.3 billion.

Botanicals and Nutritional Supplements

Cancer patients commonly use dietary supplements, most often without the guidance or expertise of a knowledgeable practitioner. Well-intended oncologists sometimes resort to asking patients to discontinue all supplements during treatment, further diminishing a patient’s sense of control over his or her own health care and promoting an attitude of nondisclosure. This lack of discourse can lead to harmful drug interactions, potentially decreasing the efficacy of some chemotherapeutic agents and radiation therapy. Opening a dialogue with patients about their supplement use helps to protect them, allows them to participate in their care, and promotes a sense of mutual respect between patient and physician. This section includes some general precautions about the use of dietary supplements; the remainder of the chapter will address some supplements and other interventions that are effective in treating common symptoms and side effects related to therapy.

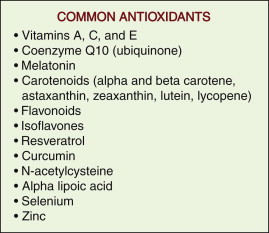

One of the more hotly debated issues regarding the use of supplements during conventional cancer care is whether antioxidants interfere with or reduce the side effects of therapy. Patients commonly start taking antioxidants when they are diagnosed with cancer because of the misperception that antioxidants prevent cancer and the assumption that what prevents cancer must also be good for treating cancer ( Figure 21-2 ). In fact, there have been no large randomized controlled trials showing that antioxidants prevent cancer or reduce overall mortality. In addition, the process of oxidation that results in the creation of free radicals is critical to the antineoplastic effects of radiation and many chemotherapeutic agents. Proponents of the use of antioxidants typically cite experimental and clinical data on tumoricidal effects, induction of apoptosis, and reduction in side effects from chemotherapy or radiation. The obvious concern is that the administration of antioxidants leads to the protection of tumor cells, as well as normal cells, from oxidative damage. To illustrate this point, consider the largest randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial done examining the use of antioxidants during radiation in a group of head and neck cancer patients. In this study 540 patients were randomly assigned to receive α-tocopherol (a component of vitamin E) and β-carotene (a component of vitamin A) or placebo during radiation therapy. The patients in the α-tocopherol and β-carotene group had fewer adverse acute reactions (although no difference in quality-of-life measures), but local recurrence was 37% more likely in this group. While future research may reveal antioxidants that help to mitigate treatment side effects without decreasing the efficacy of chemotherapy and radiation, the safest recommendation at present is to avoid antioxidants during treatment.

Interactions with chemotherapy drugs and radiation are not the only concern in this population. The most common dietary supplement-drug interactions are with anticoagulants, cardiovascular drugs, oral hypoglycemics, and antiretrovirals. These are all frequently used drugs in an aging population. Some of the more common dietary supplement-drug interactions are listed in Table 21-3 , and resources for evaluating a potential interaction are given at the end of this chapter.

| Botanical Product | Common Uses | Potential Drug Interactions and Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Ginseng, American or Asian | To improve cognition, immune function, and energy; promotes blood sugar metabolism | None known but diabetics may need to monitor blood sugars due to a potential hypoglycemic effect |

| Black Cohosh | Menopausal symptoms | None known |

| Echinacea | Prevention of colds; used for immune support in cancer patients | None known; no documented interactions with immunosuppressive drugs |

| Garlic | Hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis Prevention of colds | May enhance the effect of antiplatelet therapy and warfarin |

| Ginkgo | To improve cognition; to improve blood flow to the brain and extremities | Contraindicated in bleeding disorders; may enhance the effect of antiplatelet therapy and warfarin |

| Green tea | Reduce risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer | Can diminish the effect of dipyridamole; possible synergistic effects with sulindac and tamoxifen Large amounts of caffeine may increase the side effects of theophylline Antagonizes the tumorcidal effect of bortezomib (Golden 2009) |

| Ginger | Nausea | None known; anecdotal reports of interaction with warfarin but not proven |

| Kava | Anxiety and sleep | Should not be taken with alcohol, barbiturates, and other drugs with significant CNS effects Large doses may cause scaly ichthyosis |

| Milk thistle | Liver diseases and “cleansing” | An antioxidant; no known drug interactions |

| St. John’s Wort | Depression | Should not be taken with prescription antidepressants; may interact with oral contraceptives, warfarin, theophylline, Indinavir, cyclosporine, digoxin Avoid alcohol Induces CYP3A4 |

| Saw Palmetto | Prostate health, urinary outlet obstructive symptoms | None known; may cause mild nausea when taken without food |

Another area of concern is the adulteration of botanicals and dietary supplements. One of the more egregious abuses of the public trust with regard to the safety and integrity of herbal products was the contamination of a product known as PC-SPES and its removal from the market by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). PC-SPES was an herbal combination that was sold as a supplement to promote prostate health and was used by patients to treat prostate cancer. Preliminary trials demonstrated a decrease in PSA and testosterone with the administration of this supplement. Publicly funded, larger clinical trials were planned for PC-SPES until independent laboratories reported the presence of diethylstilbestrol (DES) in several batches of the product. Further evaluation revealed that the product was adulterated with other prescription drugs (warfarin, alprazolam, and indomethacin).

This is just one example of the quality and safety issues surrounding the use of dietary supplements. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DHSEA) required the FDA to regulate dietary supplements as foods rather than as drugs, which means that supplements do not need approval from the FDA prior to entering the market. While this ensures the availability of these products to consumers, it comes with the consequence of a lack of regulatory oversight. The FDA does have the responsibility of regulating the manufacture of dietary supplements, and as of June, 2010, all manufacturers must be in compliance with current good manufacturing practices (cGMP). Given the large number of dietary supplement manufacturers, enforcement of these regulations may be difficult.

The industry is not completely without quality control, however. Many companies undergo voluntary independent testing of their products by the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and ConsumerLab.com . Products displaying the USP verified seal or the ConsumerLab.com mark have completed this testing and been found to be of good quality.

While many physicians may not agree with the notions of patient self-diagnosis and self-treatment that are facilitated by the availability of dietary supplements, the fact remains that the practice exists. Hence the onus is on physicians to learn at least the basic essentials of indications, side effects, and potential drug interactions of dietary supplements.

Cancer-Related Problems and CAM Interventions

The remainder of this chapter provides recommendations that any physician can utilize to help cancer patients navigate the maze of treatment, side effects, and survivorship. The recommendations that follow are evidence-based. The evidence is not always from randomized, controlled trials, but it is enough to open doors to further exploration.

Nausea and Cachexia

Even with significant advances in pharmaceutical options for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea, over 70% of cancer patients still report it as a problem. Postoperative nausea may also be an unpleasant part of many cancer patients’ experiences. Acupuncture (or a similar variation) has been shown in several studies to be useful for chemotherapy-induced and postoperative nausea. In fact, the 1997 NIH Consensus Conference on Acupuncture found that there was ample scientific evidence to support a recommendation of acupuncture for the treatment of postoperative and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

A more recent review of the literature examining trials of acupuncture point stimulation in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting found that acupuncture and electroacupuncture (applying an electrical current to the acupuncture needle while inserted) were significantly more effective than placebo or noninvasive forms of acupuncture point stimulation.

Investigators at Duke University Medical Center examined the use of electroacupoint stimulation (slight electrical current applied through an electrode placed on an acupuncture point) in the treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. The participants were selected from a group of patients undergoing major breast surgery and were randomized to electroacupoint stimulation, ondansetron, or sham control (electrodes placed but without stimulation). Both treatment interventions were more effective at controlling nausea and emesis than the sham control. In addition, patients in the electroacupoint stimulation group had lower pain scores. A meta-analysis of nonpharmacologic methods of treating postoperative nausea and vomiting (acupuncture, electroacupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, acupoint stimulation, and acupressure) showed that these methods were as effective as antiemetics in preventing early and late vomiting.

Ginger ( Zingiber officinale ) is commonly used as a home remedy for an upset stomach. Traditional Chinese medicine uses ginger to treat nausea; it has also been useful in treating pregnancy-associated nausea. In a randomized controlled trial of 644 cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, ginger capsules were found to be effective at significantly reducing nausea, even in the setting of standard 5-HT 3 receptor antagonist antiemetics.

Another nutritional problem commonly encountered in oncology practices is cancer cachexia. Cancer cachexia is a condition involving complex metabolic processes, as well as reduced nutritional intake. It leads to a significant reduction in lean body mass, extreme fatigue, and ultimately immobility. In part, the metabolic hyperactivity in this condition is attributed to the production of proinflammatory cytokines. For this reason, omega-3 fatty acids as inflammatory mediators have been explored for supportive care in this condition. Several studies in pancreatic cancer patients have shown positive effects of omega-3 supplementation (especially eicosapentaenoic acid or EPA) in terms of weight gain, performance status, and quality-of-life measures. A recent review of the literature on omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of cachexia in patients with advanced cancer of the pancreas and upper digestive tract showed that supplementation with 1.5 to 2.0 grams per day of EPA and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) resulted in improvements in multiple measures; one study actually showed a significant improvement in survival.

Diarrhea and Mucositis

The gastrointestinal tract is often an innocent victim when it comes to the efficacy of therapeutic agents in destroying rapidly dividing cells. The loss of cells in the GI tract and bone marrow is sometimes the dose-limiting factor in administering chemotherapy or abdominal/pelvic radiation. In addition to routine supportive measures for diarrhea (hydration, small meals, avoiding fiber, and antidiarrheal drugs), patients may benefit from taking glutamine. Glutamine helps to maintain the mucosal integrity of the gut epithelium. In a randomized controlled trial of 70 patients who were receiving 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) chemotherapy for treatment of advanced colon cancer, oral glutamine at a dose of 6 grams three times a day significantly improved intestinal absorption and permeability compared to placebo. Another placebo-controlled trial was done in breast cancer patients receiving cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and 5-FU chemotherapy, with 30 grams of glutamine per day. These investigators showed that glutamine lessened intestinal permeability and did not interfere with chemotherapy; however, no clinical difference was seen in diarrhea and stomatitis scores. There are also case reports that glutamine has been effective in preventing late diarrhea associated with irinotecan.

Mucositis can affect up to 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy at standard doses and as many as 75% of patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy. Also, despite advances in radiation therapy, mucositis is an almost universal side effect of head and neck irradiation. Ulceration of the oropharyngeal mucosa is painful, creates difficulty swallowing and speaking, inhibits adequate nutritional intake, and can lead to delays in treatment that potentially affect tumor control. Glutamine is useful in this group of patients as well. A randomized controlled trial of 326 breast cancer patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy showed that glutamine in a proprietary drug delivery system (Saforis) significantly reduced the incidence of oral mucositis. A pilot study in 17 head and neck cancer patients receiving radiation showed a reduction in oral mucositis with administration of a glutamine solution as an oral rinse four times a day.

Xerostomia

Xerostomia, or dry mouth, is primarily caused by radiation to the head and neck region. With the development of more precise radiation treatment planning systems, better patient immobilization, and real-time imaging techniques, the incidence of permanent xerostomia has been significantly reduced, but it remains a significant quality of life issue for many patients. Acupuncture has proven to be very useful in improving salivary flow rates in patients who have received radiation to the head and neck. In one retrospective review of 70 patients with xerostomia from radiation, Sjögren syndrome, or other causes, patients received 24 acupuncture treatments; statistically significant differences were found in stimulated and unstimulated salivary flow rates compared to baseline. These results were independent of the etiology of the xerostomia. At 3 years follow-up, those who had continued to receive some acupuncture treatments had significantly more salivary flow than those who did not receive additional treatment. Johnstone et al. developed a xerostomia inventory (XI) as a validated tool to help objectively measure the effects of acupuncture, as subjective measures of xerostomia are not always consistent with objective salivary flow rates. In a report on 50 patients who had received 318 treatments, 70% of patients had a response to acupuncture as indicated by improvements in the XI. Most patients required treatment every 1 to 2 months for a lasting effect; however, in 26% of the patients, the effect lasted for 3 months or more.

Fatigue

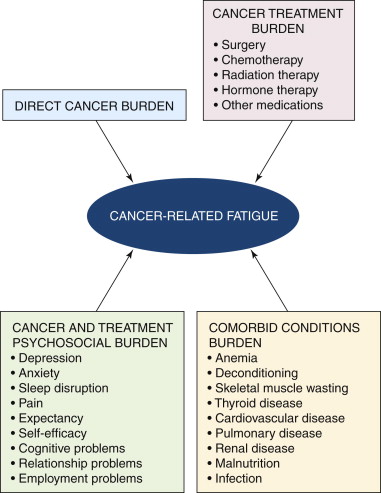

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines cancer-related fatigue as “a distressing persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity and interferes with usual functioning.” Fatigue can be the result of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation) or an effect of the disease itself. It is the most prevalent symptom reported by cancer patients, and they often need reassurance that this is a common and expected part of their cancer journey. Patients should be screened for fatigue and referred to medical professionals experienced in dealing with cancer-related fatigue. The exact etiology is not clearly understood, and there are many related conditions including anemia, nutritional deficiencies, sleep disturbances, and emotional distress that contribute to the sensation of fatigue ( Figure 21-3 ).

Nonpharmacologic evidence-based recommendations for dealing with fatigue include exercise and other activity enhancement (preferably under the direction of physical and occupational therapists), massage, yoga, meditation, and psychoeducational therapies aimed at stress reduction ( Figure 21-4 ). A recent phase II study in cancer patients with persistent fatigue after chemotherapy showed that a short course (4 to 6 weeks) of acupuncture resulted in a mean improvement of 31% in the Brief Fatigue Inventory, a finding that met predefined criteria meriting it for further study. Perhaps what is most impressive about this finding is that the group of patients studied had completed their cytotoxic therapy an average of more than 2 years earlier and the fatigue had become chronic and persistent.