A 75-year-old woman with newly diagnosed breast cancer, who has received primary treatment with surgery and radiation, has a consultation with an oncologist to discuss the need for adjuvant treatment. She goes to her appointment with her husband of 50 years who has early dementia and hearing loss. Although she has a college education, she finds the information the oncologist provides to be too complicated and therefore does not ask any questions, leaves somewhat unsatisfied, and is not even sure what the doctor ultimately recommended.

Physician-Patient Communication

Physician-patient communication is a process by which information is exchanged between a physician and patient through a common system of symbols, signs, and behaviors. Communication is a core clinical skill in the practice of medical oncology, and health literacy has a central role in cancer patients’ ability to discuss their disease and prognosis with their oncologist in a meaningful way. The average clinical career of an oncologist is approximately 40 years and can involve up to 200,000 consultations with patients and their families. As with the general population, effective communication has many positive effects on cancer patients’ adjustment to the disease and its treatment, whereas poor communication has negative consequences both for health care professionals and for patients.

Effective communication between health care professionals and patients is essential for the delivery of high-quality health care. Communication issues are often a critical factor in litigation. Research has suggested that effective communication during medical encounters positively influences patient recovery, pain control, adherence to treatment, satisfaction, and psychological functioning. Because of the threat of mortality from the diagnosis of cancer, the uncertainty of therapy efficacy, and the physical and emotional stress of undergoing chemotherapy, patients must obtain a high level of complex information during communications with their treating physician.

Older adults diagnosed with cancer are the population group considered to be at highest risk for poor communication with health professionals. The older patient is less likely to be assertive and ask in-depth questions. Overall physician responsiveness (i.e., the quality of questions, informing, and support) is better with younger patients than with older patients, and there is less concordance on the major goals and topics of the visit between physicians and older patients than between physicians and younger patients.

Communication Barriers in the Elderly

The literature suggests that evaluating such factors as memory decline and sensory deficits are essential in geriatric patient medical visits. These common age-related communication barriers are often overlooked in the oncology consultation and frequently compromise the quality of communications. There is a broad range of cognitive loss among individuals with dementia, and unless the physician is trained to uncover this problem, it can be missed in patients with mild or even moderate loss. For example, the 1999-2001 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) indicate that 2.3 million (7.1%) community-dwelling people aged 65 and older are limited by memory impairment or confusion, while 800,000 (2.4%) are limited by senility and dementia.

In addition to cognition, hearing and vision are important components of communication. Presbycusis, or decreased hearing of higher frequency sounds, is one of the most common and significant sensory changes that affect elderly people. The incidence of sensorineural hearing loss increases each decade so that by the seventh and eighth decades, 35% to 50% of older adults have hearing impairment. Vision loss also has a significant impact on physician-patient interaction, because visual cues are vital in interaction. After age 65, there is a decrease in visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, glare intolerance, and visual fields. On the basis of the 1997-2002 NHIS, 15% to 25% of older adults had visual impairment. The combination of both hearing and visual impairment among elders aged 65 to 79 was 7% and increased to 17% for individuals aged 80 and older.

Physician visits for elderly patients with these functional impairments may be so difficult to coordinate that they result in frequently missed appointments. When these frail older patients finally do see the physician, the visits may be emotionally and physically stressful for them, limiting effective communication.

Health Literacy

The Institute of Medicine defines health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” A patient’s health literacy level, which includes such skills as the ability to comprehend prescription bottle labels, follow written and oral health instructions, and understand physician dialogue, may be significantly lower than his or her general literacy level. The National Adult Health Literacy Survey (NALS) published in 2003 reported that more than 50% of the United States population older than 65 was either functionally illiterate or possessed marginal literacy skills. The largest study of health literacy conducted to date in the United States found that 30% of patients at two public hospitals could not read or comprehend basic health-related materials. In addition, 42% failed to understand directions for taking medications, 60% could not comprehend a routine consent form, and 26% did not understand the information written on an appointment slip.

Numeracy (Quantitative Literacy)

It is common for oncologists and other health care providers to use information about rates, percentages, and proportions when discussing treatment and prognosis. An important component of health literacy in the context of cancer treatment is the patient’s ability to understand these basic probability and numeric concepts. Health numeracy can be defined as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to access, process, interpret, communicate, and act on numeric, quantitative, graphic, biostatistical, and probabilistic health information needed to make effective health decisions. Although there is a correlation between prose or print literacy and numeracy, many patients have adequate literacy but poor quantitative skills. A cross-sectional study of 200 primary care patients demonstrated that only 37% of patients could calculate the number of carbohydrates consumed from a 20-oz bottle of soda that contained 2.5 servings.

Decreased numeracy competency in cancer patients may have an impact on their ability to accurately assess their own health risks. Understanding numbers is essential to comprehend risk-benefit information. Patients need to: (1) acquire information from oral discussion, text, tables, and charts; (2) make calculations and inferences; (3) remember the information (short and/or long term memory); (4) weight the factors to match their own needs and values; and (5) make trade-offs to reach a health decision. Cancer communication, especially risk communication, may be hard because the patient’s knowledge relevant to cancer is often fragmented and inaccurate. Moreover, the education and everyday experience of an older cancer patient may not ensure the numeracy and health literacy required to evaluate the complex and uncertain benefits from treatment.

Inadequate Health Literacy and Older Cancer Patients

A limited number of studies have focused on the prevalence and impact of health literacy in geriatric cancer patients. A survey of Medicare enrollees between June and December 2007 demonstrated that 34% of English-speaking and 50% of Spanish-speaking respondents had inadequate or marginal health literacy. Reading ability declined dramatically with age, even after adjusting for years of school and cognitive impairment. One study in newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients with a mean age of 67 demonstrated that low health literacy limited patient understanding of complex information regarding treatment and quality-of-life issues.

Physician Communication

The underpinning of effective verbal communication in the medical encounter is the interaction between a patient’s health literacy level and the quality of dialogue between patient and physician. “Oral literacy demand” can be defined as the aspects of dialogue that challenge patients with low literacy skills. During conversations, the general language complexity increases with the greater number of sentences in the passive voice and with faster dialogue pacing, both of which have negative effects on comprehension.

The use of technical terminology is an important component of oral literacy demand. Research done on adult literacy of genetic information presented during genetic counseling sessions suggests that literacy demand was proportional to the use of technical terms. A doctor’s choice of vocabulary can affect patient satisfaction immediately after a general practice consultation, and if the doctor uses the same vocabulary as the patient, patient outcomes improve. In addition, studies have found increased “dialogue density”—or the duration of uninterrupted speech by a physician—correlates with greater oral literacy demand. A review of 152 prenatal and cancer pretest genetic counseling sessions with simulated clients found that the higher the use of technical terms, and the more dense and less interactive the dialogue, the less satisfied the simulated clients were and the lower their ratings were of counselors’ nonverbal effectiveness.

In addition, patients with low health literacy are less likely to ask their physician to slow down the dialogue and repeat information when their understanding is compromised. Interventions to modify health care provider use of technical terms, general language complexity, and structural characteristics of dialogue can enhance overall communication by decreasing patient oral literacy demand.

Decision Making

Low levels of health literacy present challenges to any decision-making paradigm, especially in the case of complex cancer treatment decisions in the elderly. Complexity in the cancer-treatment decision process originates from the fact that selection of therapy is unique to every patient. Typically, several treatment options are possible and the oncologist and patient must together carefully weigh the risk of toxicity against the potential benefit. Patient preferences, quality of life, and social responsibilities must be considered along with the stage of disease, biologic characteristics of the tumor, and comorbid illnesses.

One important factor in decision making is “self-efficacy,” or confidence in one’s ability to understand and communicate with physicians. Patients with high self-efficacy have been found to have fewer episodes of depression and develop more realistic goals.

An important aspect of self-efficacy is the sense of control and involvement in the treatment, which has been associated with several desirable outcomes including greater patient satisfaction, increased adherence to treatment, and positive treatment outcomes in elderly patients. Evidence suggests that cancer patients who report greater self-efficacy are better-adjusted and experience better quality of life than those with low self-efficacy.

Older patients are often less assertive in communicating with physicians, less likely to ask questions, and less inclined to take a controlling role in their health care decision making. Self-efficacy is a predictor of how the patient perceives and reacts to the encounter with the physician. Studies in older breast cancer patients have shown that patients with higher self-efficacy are more likely to report that discussions with their physicians are helpful.

Caregivers/Companions and Treatment Decisions in Older Cancer Patients

The effect of family caregivers and companions on cancer treatment decisions is a frequently overlooked, yet significant influence. An estimated 20% to 50% of geriatric patients are accompanied by a family caregiver or companion during their routine medical visits. Most cancer patients share their diagnosis and current condition with a family member or companion. These members of the patient’s “social support network” are often highly motivated to help patients manage information related to their cancer treatment. They play key roles in interpretations of medical diagnosis, offering explanations, and encouraging patients to comply with their treatment plan. Their level of health literacy and actions during the medical visit are critical to defining these roles.

Patients with lower health literacy are likely to be more influenced by a caregiver or companion. Specifically directed physician interactions with these individuals, including assessing their level of health literacy and providing them with appropriate written cancer information during the oncology visit, are important opportunities to optimize communication and medical decision making.

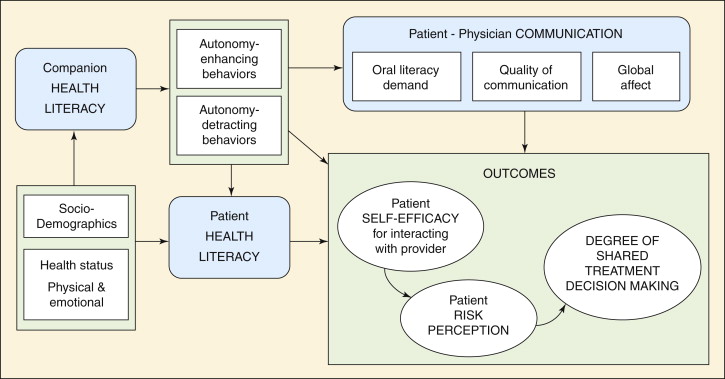

The consequences of companion behavior on patient autonomy and its impact on the decision-making process during the medical visit are important areas of investigation. Several studies have found definite benefits when a family member is present, such as an increase in the amount of medical information provided. Other researchers have determined a negative, intrusive effect of a third party on patient autonomy during a medical visit. A study of 93 patients and companions during geriatric primary care visits found more autonomy-enhancing behaviors (facilitating patient understanding, patient involvement, and doctor understanding) than autonomy-detracting behaviors (controlling the patient and building alliances with the physician). They also found that while nonspousal companions are not as active in decision making, they are more likely to facilitate patient involvement in the visit than spouses. ( Figure 12-1 .)