Common Musculoskeletal Problems

Keith J. Loud

Blaise A. Nemeth

KEY WORDS

Ankle

Hip

Knee

Musculoskeletal pain

Spine

Musculoskeletal problems, including injury, are among the most common reasons for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) to seek medical attention. Appropriate management of these concerns cannot only decrease morbidity and prevent sequelae but also earn the confidence of the patient.

This chapter outlines a general approach to all musculoskeletal complaints, highlighting those conditions that are frequently seen or are unique to AYAs, with special attention to spinal deformities.

Triage and Initial Management of Common Complaints

Health care providers for AYAs can provide most of the initial care for orthopedic problems. When patients present with pain in the ankle, knee, hip, and spine, the health care provider should be able to prioritize the most likely diagnoses and develop an initial management plan on the basis of the description of the (1) mechanism of injury or onset of symptoms, (2) factors that worsen or improve the pain, and (3) physical examination findings. Resources that are likely to be helpful to the health care provider include the following:

Reference materials to manage specific diagnoses:

Essentials of Musculoskeletal Care, 4th Edition, published jointly by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS)—a comprehensive, practical guide to the diagnosis and treatment of virtually all orthopedic problems encountered in primary care practice.

Care of the Young Athlete, 2nd Edition, an encyclopedic textbook also published jointly by the AAP and AAOS.

Sports Medicine in the Pediatric Office, by Jordan Metzl—a text and DVD that demonstrates hands-on examination techniques

The Sports Medicine Patient Advisor, by Pierre Rouzier—a thorough compilation of patient education materials including handouts with rehabilitative exercises

Rehabilitation specialists: A strong working relationship with local rehabilitation specialists, such as physical therapists and athletic trainers, in practice and in schools is essential because formal supervised rehabilitation is a mainstay in the treatment of many conditions.

Musculoskeletal specialists: Ready consultation with orthopedic surgeons and primary care sports medicine physicians when needed.

General Indications for Radiographs in Patients with Acute Trauma of an Extremity

In general, plain radiographs (x-rays) should be considered for any:

Significant unilateral complaint (with greater urgency for pain, which awakens a patient from sleep)

Unexplained or persistent bilateral complaints

General Indications for Referral to a Musculoskeletal Specialist for Patients with Acute Trauma of an Extremity

General criteria for immediate consultation regardless of the injury site include any of the following:

Obvious deformity

Acute locking (joint cannot be moved actively or passively past a certain point) or other concern for osteochondritis dissecans (OCD)

Penetrating wound of major joint, muscle, or tendon

Neurological deficit

Joint instability perceived by the adolescent or young adult or elicited by the health care provider or other concern for internal joint derangement

Bony crepitus

Treatment and Rehabilitation of Injuries—General Concepts

The prevention of long-term sequelae of injury depends on complete rehabilitation, characterized by full, pain-free range of motion (ROM) and normal strength, endurance, and proprioception.

There are four phases of rehabilitation:

Limit further injury and control pain and swelling.

Improve strength and ROM of injured structures.

Achieve near-normal strength, ROM, endurance, and proprioception of injured structures.

Return to activity (exercise, sport, or work) free of symptoms.

Since AYAs progress through these phases at different rates, avoid predicting time frames for return to participation

Phase 1: Limit Further Injury and Control Pain and Swelling

The affected part must be rested and protected, using appliances (e.g., wrap, splint, crutches, sling) as necessary to achieve pain relief. Reevaluate frequently to avoid extended use of crutches or bracing without indication.

Elevation, compression, and ice should be applied as often as possible during waking hours. Ice should be applied continuously for 20 minutes, directly to the skin and 3 to 4 times a day for the first few days.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), if prescribed, should be dosed regularly (rather than “as needed”) to achieve therapeutic steady-state levels, but limited to 5 to 10 days.

Uninjured structures should be exercised to maintain fitness and psychological health.

Phase 2: Improve Strength and ROM of Injured Structures

Relative rest is the cardinal principle, allowing activity as long as it does not cause pain within 24 hours of the activity.

Specific exercises should be done within a pain-free ROM. Isometric exercises can be started on the first day if there is little pain-free ROM but the patient is able to contract the muscles.

NSAIDs may be continued to interrupt the cycle of pain, muscle spasm, inflexibility, weakness, and decreased endurance; however, they should not be used to mask pain and allow premature return to play. In addition to reducing swelling, ice is also a good analgesic.

General fitness maintenance should continue, as described for Phase 1.

Phase 3: Achieve Near-Normal Strength, ROM, Endurance, and Proprioception of Injured Structures

Exercise is increased as long as the subject follows the relative rest principle.

Healing is characterized by minimal discomfort or laxity with provocative testing, normal ROM, no tenderness along the ligament or pain with stretching, and progressively less pain with activities of daily living.

Phase 4: Return to Exercise or Sport Free of Symptoms

Functional rehabilitation should be sport-specific, practicing components at a decreased level and advancing gradually to full-force execution.

Premature return is likely to result in further injury or another injury.

Successful rehabilitation minimizes the risk of reinjury and returns the injured structures to baseline ROM, strength, endurance, and proprioception.

In the clinician’s office, safe return to participation in physical activities can be advocated when the patient demonstrates:

Absolutely no residual deformities or edema in the injured body part. An exception to this rule is the ankle, which may demonstrate soft tissue swelling (not effusion) long after functional restoration has been achieved.

Full and equal ROM compared to the uninjured, paired joint

At least 90% muscle strength compared with the uninjured paired extremity

No pain at rest or with activity. If there is post-activity discomfort, it should resolve completely before the next activity session (practice or competition), without regular use of analgesics. Discomfort after subsequent activity sessions should not be greater in intensity than the initial session, even if it completely resolves in between.

Ankle injuries—sprains and fractures—are the single most common acute injury in adolescent athletes. The diagnosis and treatment of ankle injuries in adolescents are the same as in young adults, with the exception that early teens may have open growth plates that may be fractured, whereas in a young adult the primary injury is likely to be a sprain of ligaments.

Historical Clues

In the majority of acute ankle injuries, the mechanism of injury is inversion (turning the ankle under or in). Injuries resulting from eversion are generally more serious because of the higher risk of fracture and “high ankle sprains” (syndesmosis injury).

Physical Examination

Acute injury: The best and most informative time to examine any musculoskeletal injury is immediately after the injury. However, patients commonly present hours to days after the injury with diffuse swelling, tenderness, and decreased ROM. At this point, the physical examination will be limited in terms of diagnosing specific lesions. At a minimum, the examination should include the following:

Inspect for gross abnormalities, asymmetry, and vascular integrity.

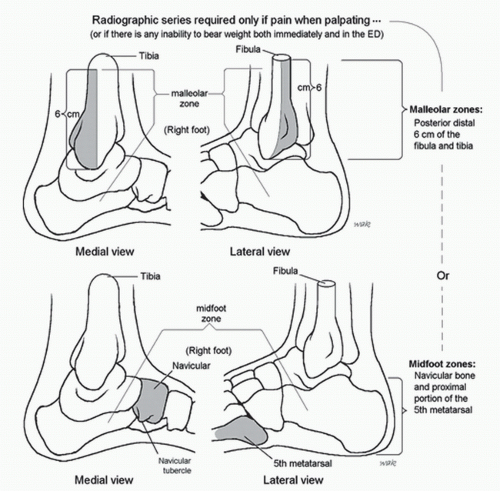

Palpate for bony tenderness specifically at the distal/posterior 6 cm of the tibia (medial malleolus) or fibula (lateral malleolus), the tarsal navicular, and base of the fifth metatarsal (Fig. 18.1).

Assess ability to bear weight.

Three to four days after injury: The physical examination may be more informative at this time, as the patient may have had an opportunity to use rest, ice, compression, and elevation.

Inspect for swelling and ecchymosis.

Assess active ROM in six directions:

Plantarflexion; plantarflexion and inversion; plantarflexion and eversion

Dorsiflexion; dorsiflexion and inversion; dorsiflexion and eversion

Assess resisted ROM in the same six directions.

Palpate again for bony tenderness.

Attempt passive ROM—plantarflexion, dorsiflexion, and inversion, which will provoke discomfort with the most common lateral ankle injury.

Assess ligamentous stability—see reference texts to perform talar tilt and anterior drawer tests.

Assess for pain-free weight bearing with normal gait and then with heel-and-toe walking.

Associated injuries: Complications associated with ankle sprains:

Fractures are common in ankle injuries that cause complete ligament tears. The most common sites are the talus, fifth metatarsal, fibula, and tibia. If there is bony tenderness in an adolescent with open physes, assume that a fracture is present even if the radiography results are negative. Immobilize without weight bearing for 1 week; if tenderness persists, casting for 2 weeks is recommended. An exception is the distal fibular physis. Many authorities will manage and monitor a presumed Salter-Harris I fracture (normal radiographs) like a lateral ankle sprain. Similarly, a small avulsion fracture at the tip of the distal fibula or tibia may be treated conservatively.

“High ankle sprains”—tibiofibular syndesmosis injury accounts for 6% of ankle sprains. These are more serious injuries than the typical lateral ligament sprain. On examination, there is tenderness proximal to the joint line along the syndesmosis. Pressing the midshaft together and then releasing the pressure may worsen the pain.

Diagnosis

Radiographic Examination: Ottawa Ankle Rules

The Ottawa Ankle Rules are a well-validated set of clinical decision rules that suggest that an ankle or foot plain radiograph is indicated if there is bone tenderness at (1) the distal/posterior 6 cm of the tibia or fibula (ankle series); (2) at the tarsal navicular; (3) at the base of the fifth metatarsal (foot series); or (4) if the patient

is unable to take four steps both immediately after the injury AND during the examination, regardless of limping (Fig. 18.1).1 Stress views are typically not indicated in the evaluation of the acute or chronically injured ankle.

is unable to take four steps both immediately after the injury AND during the examination, regardless of limping (Fig. 18.1).1 Stress views are typically not indicated in the evaluation of the acute or chronically injured ankle.

Treatment—Acute Phase

The goal is to limit disability. Successful treatment is defined by the absence of pain and by return to full ROM, strength, and proprioception. Mainstays of initial treatment are:

Relative rest, ice, compression, and elevation: Used in the same manner as described earlier

Compression and stability can be provided by an air stirrup type ankle brace, which should be used for all acute sprains not complicated by fracture. Casting is not indicated. The brace provides stability to inversion and eversion, allowing for active dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, which includes weight-bearing gait, a key to successful rehabilitation.

Stirrup braces should spare the use of crutches. If crutches are needed for significant pain, the patient should be instructed in partial weight-bearing techniques. Patients should be advised to discontinue use of crutches as soon as possible by using the brace consistently and aggressively increasing the proportion of weight bearing, guided by their discomfort.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation should start on the first day of evaluation.

Stretching: Primarily soleus and gastrocnemius, by doing calf stretches

Strengthening: Band exercises, toe-heel walking, pain free, and progressive (can be done with the air stirrup on)

Proprioceptive retraining: Raising on toes with little support (one or two fingers on a chair) and eyes closed for 5 minutes a day

Functional progression of exercise: For instance, toe walking → walking at a fast pace → jogging → jogging and sprinting → sprinting and jogging on curves → figure-of-eight running → back to sports participation

The stirrup or lace-up-type ankle brace should be worn in competition sports for 6 months after the injury.

Knee injuries and pain syndromes are among the most common chief complaints seen by musculoskeletal specialists who work with AYAs. Primary care clinicians can develop a working diagnosis and initiate treatment for the majority of these patients.

Historical Clues

Knee pain that occurs while running straight, without direct trauma or fall.

Chronic pain: Likely to be patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFS).

Acute pain: Consider OCD and pathological fracture. Any adolescent with knee pain without a history of trauma who has an examination that does not pinpoint the diagnosis should have a radiographic examination of the knee. If the hip examination is abnormal, radiographs of the hip are also needed to rule out slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) manifesting as knee pain. Osgood-Schlatter disease and PFS do not require radiographs to establish a diagnosis.

Knee injury that occurs during weight bearing, cutting while running, or an unplanned fall: Consider internal derangement

including ligamentous and meniscal tears and fracture, especially if there is hemarthrosis within 24 hours of the injury. A patient who injures the knee while cutting, without being hit or having direct trauma, has a high likelihood of having an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear or patellar dislocation.

A valgus injury to the knee (i.e., a force delivered to the outside of the knee, directed toward the midline) is likely to tear the medial collateral ligament, possibly the ACL, and either the medial or lateral meniscus.

Chronic anterior knee pain that is worse when going up stairs and/or after sitting for prolonged periods, or after squatting or running, is likely to be PFS. In general, if the patient does not give a history of the knee giving out or locking, sharp pain, effusion, the sensation of something loose in the knee, or the sensation that something tore with the initial injury, then the injury will probably not require surgical intervention or referral. At the activity site, the ability to bear weight and walk without pain is the best indicator that the injury is probably not major and does not need immediate referral.

Physical Examination

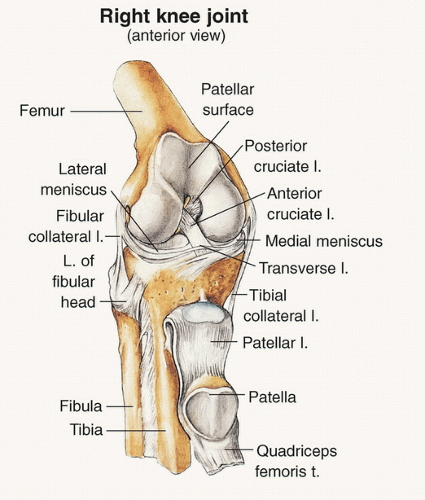

Knee anatomy is shown in Figure 18.2. The physical examination should include the following:

Observation of gait (weight bearing? antalgic gait?)

Inspection for swelling and discoloration

Observation of vastus medialis obliquus contraction, looking for reduced bulk and tone

Peripatellar palpation (tenderness over the tibial tuberosity is diagnostic of Osgood-Schlatter disease; peripatellar pain is characteristic of patellofemoral dysfunction)

Observation of quadriceps and hamstring flexibility

Examination for evidence of ligamentous instability, including valgus and varus testing (for medial collateral and lateral collateral ligaments, respectively)

Examination for evidence of meniscal tears (McMurray and modified McMurray tests), ACL tears (Lachman and pivot shift tests), and posterior cruciate ligament tears (sag sign and posterior drawer test) requires practice and experience; the reference materials demonstrate examination techniques for readers who wish to learn these skills.

Diagnosis

Radiographic Evaluation of Knee Injuries

According to the Ottawa Knee Rule, another validated clinical decision rule, a radiograph is indicated after an acute knee injury if any one of the following criteria is present:

Inability to bear weight

Fibular head tenderness

Isolated tenderness of the patella

Inability to flex the knee beyond 90 degrees

These decision rules have been shown to have a sensitivity of 100% in detecting knee fractures in adults and could potentially reduce the use of plain radiographs by 28%.2

Anteroposterior and lateral views are standard. The sunrise view details the patellofemoral joint and should be ordered if patellar dislocation is suspected, while the tunnel view should be ordered if suspicious for OCD, ACL injury, or other intra-articular pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation is not routinely indicated in the acute or chronically injured knee. MRI should be reserved for diagnostic dilemmas and for patients who do not respond to conservative management, as it adds little to a history and physical examination performed by an experienced clinician in the diagnosis of knee injuries.

Acute Traumatic Knee Injuries—General Principles of Treatment

Establish a working diagnosis.

Use the Ottawa Knee Rule.

Relative rest: Prescribe use of crutches if the patient cannot bear weight without pain or there is suspicion of fracture. An elastic wrap is adequate in the initial phase of treatment or until there is a definitive diagnosis and treatment plan. Knee immobilizers have a limited role in the management of acute knee injuries because they are bulky and awkward, and limit return of ROM. However, if a fracture has been ruled out and the clinician is concerned about patellar or joint instability, a brace can allow for safer weight-bearing gait.

Start isometric quadriceps contractions on the first day if possible. If the patient cannot contract the quadriceps and it is anticipated that he or she will be unable to do so for several days, consider an electrical stimulation unit to contract the quadriceps until the patient can do so.

Anterior Knee Pain Syndromes—Differential Diagnosis and Approach to Management

Anterior knee pain syndromes are among the most common diagnoses in sports medicine clinics that serve AYAs.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

Definition: PFS, patellar malalignment syndrome, or patellofemoral dysfunction is a frequent cause of knee pain among AYAs, accounting for as much as 70% to 80% of knee pain problems in females and 30% in males. It is also the leading cause of knee problems in athletes. The condition had traditionally been known as chondromalacia patellae. However, this term has largely been abandoned because it implies softening and damage to the patellar articular cartilage, which is infrequently demonstrated on MRI or arthroscopy. The term patellofemoral pain syndrome is a better descriptive term for part of the pathophysiology of the condition.

Etiology: PFS is often a result of abnormal biomechanical forces that occur across the patella. Even in an individual with normal anatomy, the force that occurs in this area is tremendous, especially when the body is supported with one leg and the knee is partially flexed. Abnormal forces can result from the following:

Quadriceps femoris muscle imbalance or weakness or abnormality in the attachment of the vastus medialis

Altered patellar anatomy, such as a small- or high-riding patella

Increased femoral neck anteversion, with associated knee valgus and external tibial torsion, which increases lateral stress on the patella

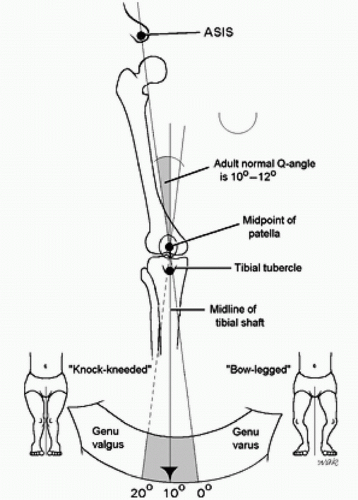

Increased Q-angle—the angle found between a line drawn from the anterosuperior iliac spine through the center of the patella and a line from the center of the patella to the tibial tubercle (normal, <15 degrees) (Fig. 18.3)

Variations in the patellar facet anatomy

Epidemiology: PFS is common in both male and female athletes. There is a higher prevalence among females in the general population but a higher prevalence among males in athletic populations.

Clinical Manifestations:

The pain of PFS is characterized by the following:

Peripatellar or retropatellar location

Relation to activity: The pain usually increases with activities such as running, squatting, or jumping, and decreases with rest. Often, the pain is worst immediately on getting up to start an activity after sitting.

Insidious onset

Positive movie or theater sign: Prolonged sitting with flexed knee is uncomfortable.

Pain is often severe on ascending or descending stairs.

Knees may seem to buckle, especially when going up or down stairs, but do not give way.

Crepitus or a grating sensation may be felt, especially when climbing stairs.

History of injury to the patella area may be present.

Symptoms are bilateral in one-third of AYAs.

Two-thirds of patients have at least a 6-month history of pain.

Physical examination

Inspection of the patient with PFS may reveal anatomical abnormalities, but often does not.

Dynamic patellar compression test, or “grind sign,” may be performed by compressing the superior aspect of the patella between thumb and index finger as the patient actively tightens the quadriceps in 10 degrees of flexion. Pain is elicited if retropatellar PFS is present. Direct compression of the patella against the femur with the knee flexed will also elicit pain. This is not a sensitive test because it can also elicit pain in the normal knee.

Active knee ROM is usually normal but hamstrings are often tight.

Joint effusion usually does not occur but can be present in severe cases. Swelling, when appreciated, is related to peripatellar bursitis.

Decreased bulk of the area around the vastus medialis on the affected side may be present.

Diagnosis: The diagnosis is usually made by compatible history and physical examination. Radiographs usually are of little help but are important in excluding other conditions. They should include anteroposterior, lateral, tunnel (to rule out OCD), and tangential views (also known as skyline or Merchant views). Hip disorders often manifest as vague knee or thigh pain, especially SCFE.

Treatment:

Control of symptoms as described earlier

Muscle strengthening: Most patients benefit from a formal physical therapy evaluation and can then be moved to a home program. As soon as tolerated, muscle-strengthening exercises should be performed at least once a day. Initially, these should be isometric quadriceps exercises (straight-leg raises). Strengthening of the vastus medialis is particularly important. Stretching of the hamstrings is an essential component of most therapy programs.

Graduated running: After symptoms are controlled and 6 to 10 lb of weight are held in straight-leg raises, a graduated running program can be instituted. Ice may be helpful immediately after exercise.

Maintenance: When the condition is under control, a maintenance program of quadriceps and hamstring exercises should be done 2 to 3 times a week. Most patients respond to nonoperative management.

Knee braces: Use of knee braces in patients with PFS is controversial. Theoretically, they keep the patella from moving too far laterally. However, because the patella moves in various planes, knee braces are best used in patients with lateral subluxation visible on examination. The knee brace is not a substitute for muscle-strengthening exercises.

Taping the knee: Although this may reduce friction, results are also controversial.

Footwear: Athletic shoes are in a near constant state of evolution, but the quality and age of the athletic shoes are more important than a particular brand name.

Over-the-counter arch supports or custom orthotics: These can be helpful to some patients. Custom orthotics are expensive and are generally not required, but in some patients these may be more helpful than over-the-counter supports.

Surgery: This is considered as a last resort for patellofemoral pain.

Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Definition: Osgood-Schlatter disease is a painful enlargement of the tibial tubercle at the insertion of the patellar tendon. It is a common problem, especially among active adolescent males.

Etiology: During development of the anterior tibial tubercle, a small ossification center develops in the largely cartilaginous tubercle. With puberty, developing muscle mass places this small area under great traction stress from the patellar tendon. Small fragments of cartilage or of the ossification center can be avulsed. The problem is often aggravated by activities that involve quadriceps femoris contraction, such as running and jumping.

Epidemiology:

Prevalence is higher in males than females.

Mean age at onset: Onset usually coincides with the period of rapid linear growth.

Females: 10 years, 7 months

Males: 12 years, 7 months

Clinical Manifestations:

Point tenderness and soft tissue swelling over the tibial tubercle

Normal knee joint with full ROM

Unilateral involvement more common than bilateral involvement

Duration usually lasts several months but can last longer.

Diagnosis:

History: Pain at the tibial tubercle, aggravated by activity and relieved by rest

Physical examination: Tenderness and swelling of the tibial tubercle

Radiograph: Not essential for diagnosis but generally done only to eliminate the possibility of other processes. The radiograph may reveal soft tissue swelling anterior to the tibial tubercle and/or fragmentation of the tibial tubercle.

Therapy: Since this is also an anterior knee pain syndrome, rehabilitation proceeds as for PFS. In addition:

Explanation: Careful explanation of the condition to the adolescent and parents is essential to alleviate fears and misconceptions.

Restriction of activity: If symptoms are mild, the patient may continue in the chosen sport. If symptoms are more severe, limiting running and jumping activities for 2 to 4 weeks is usually sufficient.

Immobilization: If symptoms are severe or fail to respond to restriction of activity, immobilization with a knee immobilizer for a few weeks is effective. Immobilization should also be strongly considered when the patient has difficulty actively bringing the knee to full extension.

Knee pads: Knee pads should be used for activities in which kneeling or direct knee contact might occur.

Surgery: Surgery is rarely indicated. If the patient continues to have symptoms after skeletal maturity, there may be a persistent ossicle that has not united with the rest of the tibial tubercle. Simple excision of this fragment may bring relief.

Prognosis: The prognosis is excellent, but adolescents should be informed that the process might recur if excessive activity is performed. When growth is completed, the problem usually stops, leaving only a prominent tubercle. The patient may still have difficulty kneeling on the prominent tubercle, even into adulthood. Rarely, patients with Osgood-Schlatter disease may fracture through the tibial tubercle.

Osteochondritis Dissecans

OCD is an important idiopathic condition of focal avascular necrosis in which bone and overlying articular cartilage separate from the medial femoral condyle, or less commonly, from the lateral femoral condyle. The peak incidence is in the preadolescent age-group. The clinical course and treatment vary according to the age at onset, with children and young adolescents having a better prognosis than older adolescents and adults. Insidious onset of intermittent, nonspecific knee pain that does not respond to PFS treatment should raise suspicion for OCD, especially if associated with intermittent effusion or a sensation of knee locking. Diagnosis of OCD should prompt referral to a musculoskeletal specialist.

Hip pain is a less common reason for AYAs to seek musculoskeletal care, but the differential diagnosis includes a true orthopedic surgical emergency, SCFE, which must be recognized by clinicians caring for this population.

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Definition

SCFE is a disease in which the anatomic relationship between the femoral head and neck is altered secondary to a disruption at the level of the physis. A “stable” slip progresses slowly with insidious onset of pain. “Unstable” slips present acutely with inability to bear weight and represent a surgical urgency.

Etiology

The femoral head slips posteriorly, inferiorly, and medially on the femoral metaphysis. This occurs through the hypertrophic cell layer of the epiphysis that widens during the accelerated growth of puberty. Obesity may alter the mechanics, increasing the vector of shear force acting at the physis, in addition to the increased forces caused by excess body weight itself.

Most cases of SCFE are unrelated to an endocrine disorder, although the disease has been associated with hypopituitarism, hypogonadism, and hypothyroidism, all having increased risk for bilateral slips. Endocrine abnormalities should be considered in patients at the extremes of the adolescent age-group (before age 9 or after age 16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree