Rectum

Sigmoid and left colon

Transverse colon

Right colon

Ileum

Deep ulceration (12 if present, 0 if absent)

0+

0+

12+

12+

/

Superficial ulceration (6 if present, 0 if absent)

0+

0+

6+

6+

/

Surface involved with the disease (cm)

0.0+

2.0

8.0+

6.0+

/

Ulcerated surface (cm)

0.0+

0.0+

6.0+

1.5+

/

In this table, four anatomical regions were examined because the ileum could not be entered.

Total 1 = 0 + 0 + 12 + 12 = 24

Total 2 = 0 + 0 + 6 + 6 = 12

Total 3 = 0.0 + 2.0 + 8.0 + 6.0 = 16

Total 4 = 0.0 + 0.0 + 6.0 + 1.5 = 7.5

Total A = Total 1 + Total 2 + Total 3 + Total 4 = 59.5

The number of anatomic regions examined as total or partial is n = 4.

Total B = Total A/n = 59.5/4 = 14.87

If there is ulcerated stenosis and nonulcerated stenosis, these values are also included:

CDEIS = Total B + C + D = 14.75 + 3 + 3 = 20.75

The Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) offers a simpler classification. The four factors in the SES-CD index are ulcer size, percentage of ulcerated surface area, percentage of affected areas, and narrowing of the lumen. If there is no ulcer, 0 point is given; 1, 2, or 3 points are given for aphthous ulcers, which have diameters 0.1–0.5 cm, 0.5–2 cm, or greater than 2 cm, respectively. If there is no ulcerated area, 0 point is given; 1, 2, or 3 points are given for an ulcerated area smaller than 10 %, 10–30 %, or greater than 30 %, respectively. If there is no affected area, 0 point is given; if the affected area is less than 50 %, 50–75 %, or greater than 75 %, 1, 2, or 3 points are given, respectively. In scoring according to the presence of narrowing, if there is no narrowing, 0 point is given; 1 point is given for a single narrowing that the endoscope can pass, 2 points are given for multiple narrowings that the endoscope can pass; if endoscope cannot pass, 3 points are given [205].

Colorectal Cancer Screening in Patients Diagnosed with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Patients with ulcerative colitis are at increased risk of developing colon cancer. The duration and extent of the disease in the colon are proportional to the risk [206]. Ulcerative colitis increases the risk of colorectal cancer 2.4-fold [207]. The pathological changes observed in the colon may indicate transformation from nondysplastic changes to dysplasia, low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and cancer [208]. The risk of colorectal cancer increases significantly in Crohn’s disease. The development of colon cancer was observed in the ileocolic area, diseased segment of the colon, and fistula [209].

The British Society of Gastroenterology recommends that screening colonoscopy should be performed for all patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease 10 years after the onset of symptoms of colitis. Surveillance colonoscopy should be carried out when the disease is in remission. Cancer risk of inflammatory bowel disease is directly proportional to the duration and extent of the disease, and additional risk factors are primary sclerosing cholangitis and family history of colon cancer. Screening intervals are recommended in these cases. Surveillance colonoscopy is recommended every year for the high-risk groups, every 3 years for the intermediate risk group, and every 5 years for the lower risk group [210].

According to the American College of Physicians, colonoscopy is recommended every 2 years in inflammatory bowel disease, after 7 years for pancolitis, or 12–15 years after the start of left-sided colitis [211].

If colorectal screening in colonoscopic examination is performed in the period of active colitis, colon cancer may be missed. Colonoscopy should be done in the remission of the disease. Fecal calprotectin rises during active inflammation of the disease. Some researchers have reported that fecal calprotectin concentrations can be used for the timing of colonoscopic examination. Chromoendoscopy is recommended for the recognition of dysplastic lesions because these lesions are often subtle and flat [212].

Follow-Up After Polypectomy

Colon polyps are lesions showing growth toward the colon lumen from the inner surface of colon. These may be stalked or sessile polyps. According to the histological classification, they can be classified as neoplastic and nonneoplastic (hyperplastic, hamartomatous, and inflammatory). Neoplastic polyps are adenomatous polyps and have tendency to transform to malignant. Adenomas can be classified as tubular adenoma, villous, tubulovillous, and serrated. Polyps, according to colonoscopic view, can be classified as sessile (flat) and pedunculated [213, 214].

Colonoscopy after polypectomy is a recommended method for following patients. If colonoscopic surveillance is performed frequently and with unnecessary intervals, endoscopy centers would be busy unnecessarily and patients exposed to frequent colonoscopy complications. Adenoma is often encountered in colorectal screening. In autopsy studies, adenomas have been identified more often in men. Development of colorectal cancer derived from adenoma was first reported at St. Mark’s Hospital in London and then later by Morson. Morson reported that cancer may develop after the adenoma. Endoscopic polypectomy can prevent colorectal cancer development due to it cuts adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Therefore, colonoscopy and colonoscopic polypectomy are increasingly applied [215–217].

The first colonoscopy should be performed in a complete and careful manner in order to perform colonoscopic follow-up after polypectomy. It is required to perform full colon cleansing, to reach the cecum, and to display of all segments of the colon. If this cannot be done, the full colonoscopic examination must be completed by performing colonoscopy in short intervals. Small rectal hyperplastic polyps are considered as a normal. The next control colonoscopic examination may take place 10 years later. Patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome have an increased risk of colorectal cancer. These patients have large, multiple, proximal hyperplastic polyps phenotypically. It is recommended to remove all polyps in these patients. If polyps cannot be removed endoscopically, surgical resection should be considered. The optimal treatment and surveillance protocol for such patients is unknown. More intensive follow-up should be done [216, 218, 219].

Colonoscopic follow-up may be performed at 5-year intervals in patients with one or two small (<1 cm), low-grade tubular adenomas. These patients are accepted in the low-risk group. Some studies recommend performing control colonoscopy within 3 years for patients with between 3 and 10 small adenomas or an adenoma 1 cm or greater in diameter, any adenoma with a villous character, or high-grade dysplasia. However, some authors recommend performing colonoscopy after 3 years for the patients with 3 to 4 small adenoma or adenoma 1 cm or greater in diameter, considering them as intermediate risk. They recommend performing colonoscopy 1 year later for patients with 5 or more small adenomas or at least 3 adenomas 1 cm or greater in diameter, considering them as higher risk. Adenomas must be completely removed. Piecemeal removal is not complete removal. If piecemeal removal is performed, complete removal of the adenoma should be done. If there are more than 10 small adenomas, colonoscopic follow-up should be performed in shorter periods. If piecemeal removal is performed, close follow-up should be made (2–6 months) and complete removal should be provided. If there is family history, closer follow-up should be done [216, 220].

Follow-Up After Colorectal Cancer Surgery

Recurrence can develop in almost half of patients with colorectal cancer despite neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatments, modern surgical techniques, and the pathological classifications that have been developed for primary and metastatic lesions. This recurrence may be colonic or extracolonic. Colonoscopy may be used for colorectal cancer surveillance and early detection of recurrence [221].

The purpose of surveillance colonoscopy performed after colorectal cancer surgery is the detection of local recurrence and metachronous lesions. Metachronous cancer is multiple primary tumors developing at intervals [222, 223].

The anastomosis line corresponds to the proximal and distal ends of the segment that has been resected. In particular, the proximal and distal end of the anastomosis should be examined carefully in colonoscopy. Colon cleansing should be done well and all colon segments should be observed. Colonoscopy is performed by entering the colostomy opening in patients without colon anastomosis. The anatomical path of the colon shows changes in end colostomy and enters into the abdomen by passing through the front wall of the abdomen. The colon, which enters into the abdomen, can make a slight angulation or can switch to the normal anatomic position by making a sharp angulation. This postoperative change must be passed carefully by the endoscopist. A problem with inflating the colon with air can occur due to the lack of adequate sphincter structure around the colostomy and the expansion of the colon and sufficient observation cannot be achieved. Colonoscopic examination should be performed carefully and patiently in these circumstances. Hartman surgery is performed in some of patients with colorectal cancer, in which rectum is left in place and, after resection, the proximal colon is opened as end colostomy, and the distal part is closed primarily. In these patients, rectal examination for surveillance is performed endoscopically, and it should be noted that the remaining rectum may be too short. In laparotomy performed for mechanical intestinal obstruction, loop colostomy is opened in cases where cancer cannot be resected for the treatment of obstruction. In these patients, the rectum remains in place and colonoscopic examination is required after chemoradiotherapy treatment. While the rectum is examined endoscopically in these patients, if there is any amount of opening in the lumen of rectum, air passing into the rectum moves to colon, passes from the colostomy, inflates the colostomy bag, and may cause dislocation of the bag. While colonoscopic examination is performed for loop colostomy, one side of the colostomy will move toward the distal where the tumor is found. The other end of the colostomy moves to the proximal. While investigating the proximal end, recurrent or metachronous tumor should be investigated by reaching up to the cecum. Rectum cleansing can be provided with enema before rectal examination. Oral laxatives can provide the cleansing of the proximal part of colon. Enema, which is applied to the distal part of the colostomy, is useful in patients with loop colostomy for cleaning the distal colon segment, however, care must be taken not to perforate the colon during this process. There are different views for the surveillance colonoscopy after colorectal surgery. In 2006, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer recommended surveillance colonoscopy at 1 year, 3 years, then every 5 years [224].

Colorectal Cancer Screening

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer [224, 225]. It is seen more frequently in Australia, New Zealand, Europe, and North America and less often in Africa and South-Central Asia. It is more common in men than in women [226]. Incidence and mortality rates increase with age. Ninety percent of new cases are in patients older than 50 years. Cancer is mostly seen in the rectosigmoid region [227]. Screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer has been implemented in the United States and some European countries [228].

The US Preventive Services Task Force made recommendations in the screening program for colorectal cancer. Fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy are recommended for colorectal cancer screening between 50 and 75 years of age. Sigmoidoscopy is recommended every 5 years or colonoscopy is recommended every 10 years. Fecal occult blood testing is also recommended in combination with sigmoidoscopy every 3 years [229].

Increased risk factors for colorectal cancer are present for some people and include family history, familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, obesity, red meat consumption, smoking, and alcohol consumption. In such cases, cancer screening is recommended to begin before age 50. Levin et al. recommended colonoscopy between ages 10 and 12 in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Colonoscopy is recommended for cases diagnosed with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) genetically or clinically between ages 20 and 25 or 10 years before the youngest case in the immediate family [210, 227, 230].

Mass Lesions

Intra-abdominal masses can be noticed by the patient or be detected by doctors during examination of the abdomen. These masses can be detected incidentally during imaging procedures. When any intra-abdominal mass is detected, the organ that the mass is derived from is important. Another issue that needs to be resolved is whether the mass is a primary tumor formation of the organ or a metastatic mass to the organ.

Intra-abdominal neoplasm metastases occur via hematogenous spread, lymphatic spread, direct invasion, and intraperitoneal seeding. The settlement of intraperitoneal seeding may be incidental or the nearest location to the tumor or connected to ascitic fluid circulation. The peritoneal cavity has a barrier transversely with the transverse mesocolon. The small intestine mesentery creates an oblique barrier from the spleen to the cecum. Below, the two mesos are merged at the junction of the terminal ileum and cecum. These barriers constitute flow paths within the peritoneal cavity and are areas in which peritoneal seeding can occur due to this ascitic fluid circulation. Seeded metastases occur mostly in the pouch of Douglas, the right lower quadrant, the sigmoid colon, and the right paracolic gutter. In colon cancer, it is possible to find metastatic masses in these regions due to peritoneal seeding [231].

In one study, synchronous liver metastasis was found in 14.5 % of colon cancer. In colon cancer, while 76.8 % of synchronous metastasis was found in the liver, 23.2 % was observed in other visceral organs. Metachronous liver metastases increase over the years. Metachronous liver metastasis is observed in the first year by 4.3%, this rate rises to 16.5% in the fifth year [232].

Desmoid tumors are tumoral formations caused by fibroaponeurotic tissue. These can form very large masses in the abdomen and can make formations similar to plaques on the small intestine mesentery. These plaques can lead to the formation of adhesions between the intestine and ileus. Intra-abdominal desmoid tumors are common in patients with familial polyposis and constitute the most common secondary cause of death in familial adenomatous poliposis (FAP) patients after colon cancer [233, 234].

An intra-abdominal mass can sometimes be detected accidentally during surgery. For example, it may be encountered with tumoral masses in the abdomen during an appendectomy or during laparotomy performed due to penetrating stab, gunshot injury, or traffic accident. In this instance, the reasons requiring urgent surgical intervention must be operated first. Rather than making a radical attempt to remove the encountered intra-abdominal mass, investigating the cause of this mass and taking a biopsy may be more appropriate. Imaging techniques (ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) can be used in the presence of intra-abdominal masses like this for differential diagnosis. Colonoscopy would be appropriate to determine whether the origin is the colon. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy, diagnostic laparoscopy, and laparoscopic biopsy are methods that can be applied in the histopathological diagnosis of an intra-abdominal mass according to the patient’s condition.

Intracolonic Pathologies Identified by Other Imaging Techniques

Imaging methods are used for diagnosis in patients presenting with a variety of abdominal complaints. These imaging methods include direct abdominal radiography, opaque enema colonography, ultrasonography, CT, and MRI. Although pathologies in the colon lumen cannot be displayed in direct abdominal radiograph, it is possible to display the air-fluid concentration and the concentration of obstruction. If obstruction is at the concentration of the colon, colonoscopy performed early in these patients may be helpful in diagnosis. Colon cleansing should not be done with oral laxatives in these patients as they may cause perforation. Colonoscopy can be performed with colon cleaning with enema and distal to the obstruction, and intracolonic pathologies can determine the causes of obstruction. Mucosal lesions in the colon lumen can be determined in opaque enema colonography. Definitive diagnosis can be reached in these patients as a result of colonoscopic examination. Definitive diagnosis can be made by colonoscopic biopsy when there is no possibility of taking biopsy with barium enema opaque colonography. Colon wall thickening, lumen narrowing, or mucosal lesions that reach a certain size in the colon lumen can also be detected with abdominal CT, ultrasonography, and MRI. The lesions in these patients can be visualized with colonoscopic examination, and definitive diagnosis can be made by taking a biopsy [235–238].

Unexplained Weight Loss

There are many causes of weight loss. The reason may be medical, psychological, or social. Medical causes include cardiac disease (congestive heart failure), respiratory system diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tuberculosis, etc.), gastrointestinal system disorders (such as malabsorption, atrophic gastritis, etc.), endocrine disorders (hyperthyroidism, diabetes mellitus), graft-versus-host disease, neurological diseases (such as Alzheimer’s disease), infection (pneumonia, gastroenteritis, AIDS), malignancy, physical disability (arthritis), alcoholism, drug abuse, or inability to feed resulting from disorders of tooth structure. Psychological causes include delirium, dementia, and depression. Social reasons include poverty, isolation and inability to prepare meals, and failure to provide their own care [239–241].

Unexplained weight loss is a common condition in patients with malignant disease. Decreased appetite, decreased food intake, hypermetabolism, systemic inflammation (C-reactive protein ≥10 mg/L) has been implicated in the loss of weight for these patients [242, 243].

Radiological imaging methods can be used for diagnosis in patients with suspected malignancy. Colonoscopy is the preferred method for differential diagnosis of colorectal malignancy.

Colonoscopy for Other Various Reasons

Colonoscopy can be performed for the detection of congenital anomalies, sigmoid volvulus correction, and colorectal stenting procedure in colonic obstruction. [244]. The contraindications of colonoscopy are examined in more detail below.

Topics Related to Colonoscopy Contraindications

Absolute Contraindications

Intestinal Perforation

Colon perforations may develop as a result of penetrating or blunt abdominal trauma. Penetrating trauma may occur for many reasons, such as bullet wound, knife injuries, and occupational accidents. Blunt trauma may occur as a result of traffic accidents, falls from height, or dents caused by occupational accidents. Colon wall integrity is impaired with perforations leading to a hole between the colon lumen and peritoneal cavity. Colon perforations may be alone or combined with adjacent organ injuries. Perforations occur as a result of complications of diseases other than trauma. The danger of perforation is present in sigmoid diverticulitis. Perforation risk of the terminal ileum is present in typhoid. Perforation may be seen in ischemic colitis and toxic megacolon. Such diseases may cause perforation in the colon and lead to leakage of the contents of the colon into the peritoneal cavity [105, 245–248].

In terms of bacterial load, the colon is the part of the gastrointestinal system containing the most pathogenic bacteria. There are many aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in the colon. Bacteria passing into the peritoneal cavity due to perforation may lead to intra-abdominal sepsis. The transition of bacteria into the bloodstream accelerates with intra-abdominal sepsis and can lead to the death of the patient from septicemia, septic shock, and multiorgan failure. Therefore, colonoscopic examination is contraindicated in perforated colon [249].

Sometimes the signs of perforation cannot be observed with imaging techniques in cases of stabbing wounds to the perianal region. Free air may not be found on direct abdominal X-ray in the standing position, intra-abdominal air and free fluid cannot be detected with ultrasonography, and the findings of intra-abdominal perforation cannot be observed with abdominal computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Perforation cannot be detected by imaging methods if the stab tracing is close to the rectum or the rectal laceration is not intraperitoneal because the location of perforation may be outside the peritoneal cavity in the pelvis. Rectoscopy may be performed with low pressure if deemed necessary by the clinician to support the diagnosis, as the diagnosis of rectal perforation may require surgical treatment. The authors had two such cases. In the first case, the rectal injury was 2–3 cm above the anal sphincter and was repaired with transanal rectal primary suture; the patient was discharged without any problem. In the other case, the injury was 6–7 cm above the anal sphincter and a temporary colostomy was opened for this patient. No complications of colonoscopy developed in either of these cases. Such cases are rare. Rectoscopy can be performed in a clean rectum if it is very necessary and the surgeon deems that it is appropriate.

Surgery is the treatment of colon perforation. To maintain hemodynamic stability before surgery, initiation of antibiotic treatment may help reduce morbidity and mortality. In surgical treatment, the options of primary suture, colostomy, and resection are considered according to the condition of perforation, the time passed after perforation, and the condition of the colon wall (edematous or normal) and colon (dirty or clean).

Acute Peritonitis

Acute peritonitis is an inflammatory reaction of the peritoneal cavity. Peritonitis may occur due to microbial as well as nonmicrobial causes (familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), primary peritonitis). Severe abdominal pain is present among patients’ complaints with peritonitis. Examination findings include abdominal tenderness, muscular defense, and rebound [250].

Acute peritonitis may develop due to perforation of organs. Among these organ perforations, peptic ulcer perforation, gall bladder perforation due to cholecystitis, perforation of the small intestine due to typhoid, appendix perforation due to acute appendicitis, and perforation of colon due to colon pathologies can be considered. Intra-abdominal free air is detected in the perforations of organs with lumen, and this free air is detected as subdiaphragmatic free air on direct abdominal X-ray in standing position. If the patient cannot stand up, free air can be detected if the patient lies on the left side. If the patient lies on the right side and an image is taken, this can lead to difficulties in terms of diagnosis as fundus air may be confused with free air. Tomography of the abdomen can be used for free-air recognition. Free fluid in the abdomen is detected in cases with perforation. The content of the digestive tract passing into the peritoneal cavity from the perforation region is detected as free fluid in the abdomen. Ultrasonography, CT, or MRI are able to show it. In perforation due to acute appendicitis, localized or pelvic free fluid can be determined in addition to findings of peritonitis. Peptic ulcer perforation has sudden onset of abdominal pain. Generalized peritonitis develops and diffuse muscular rigidity is present in the abdomen, which is described as board-like rigidity. In the gall bladder, perforation increases right upper quadrant pain due to acute cholecystitis and muscular rigidity is usually localized to the right upper quadrant. Muscular rigidity due to acute appendicitis is usually localized to the right lower quadrant. However, sometimes, gastric content flows toward the right lower quadrant in peptic ulcer perforation, and this may be confused with acute appendicitis signs due to tenderness that may be localized to the right lower quadrant. It is useful to keep in mind that clinical symptoms may have variations. There are underlying diseases in colon perforation, such as toxic megacolon, fulminant colitis, and sigmoid diverticulitis, and abdominal tenderness, muscular defense, and rebound continue increasing with the severity of clinical symptoms. The treatment of peritonitis due to perforation is surgery. Preoperative fluid and electrolyte resuscitation and antibiotics will increase the success of treatment. Surgical treatment can be done as open surgery or laparoscopic surgery [251–254].

Peritonitis can develop in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis as a result of infection of periton. Peritoneal dialysis fluid may become purulent. Culture and antibiogram will help in guiding treatment [255].

Peritonitis is present in acute pancreatitis. Abdominal pain that can be felt around the epigastrium and umbilicus, muscular defense, and rebound may develop. Pancreatitis attack can be regressed with medical treatment, otherwise, necrosis may develop and it may progress to necrotizing pancreatitis. Clinical symptoms can progress to sepsis and multiorgan failure with the settlement of bacteria on the areas of necrosis [256]

Mesenteric ischemia and necrosis can lead to extensive intestinal necrosis. The pain is very severe in these patients and is not relieved by analgesics. Ischemia pain causes great distress in the patient. In these patients, abdominal tenderness, muscular defense, and rebounds are present. The progression of intestinal necrosis will lead to a deepening of the septic shock in patients. Early diagnosis is very important for these patients. Viewing the mesenteric arteries (Doppler ultrasonography and CT angiography) may reveal the obstruction in mesenteric vessels. Embolectomy allows restoration of the mesenteric circulation in patients with a diagnosis of mesenteric embolism and leads to recovery as it prevents intestinal necrosis. Otherwise, necrosis develops as a result of embolism; this situation may lead to short bowel syndrome. Short bowel syndrome can sometimes lead to the loss of the patient’s life [257].

Peritonitis is generalized or localized in the digestive tract fistula. If the fistula was derived from the biliary tract, the bile, which is rich in digestive enzymes, exudes into the peritoneal cavity. If the fistula was derived from the duodenum, it contains pancreas, stomach, and bile secretion, and it has rich content including digestive enzymes. If the fistula was derived from the colon, there is quite a lot of bacterial load in the fluid of the fistula. The treatment is medical or surgical depending on the amount of fluid coming from the fistula.

If the etiology of peritonitis belongs to the colon (such as appendicitis, sigmoid diverticulitis), the colon wall is inflamed and colonoscopy can lead to perforation. In peritonitis, the adjacent colon walls also associate to inflammatory events in the abdomen. Inflammatory changes, edema, and friability secondary to peritonitis in a segment of the colon wall or the entire colon occurs. In patients with peritonitis, colonoscopy evokes extreme pain with the air introduced into the colon. In addition, colonoscopic examination will increase the risk of perforation of the colon because the colon wall is also involved in the intra-abdominal inflammatory event.

Complete or High-Grade Intestinal Obstruction

Intestinal obstruction may occur at any point of the gastrointestinal tract. The obstruction may be complete and not allow the passage of any material. The obstruction may be partial and allow the passage of gases or some amount of liquid. The concentration of obstruction may be at the concentration of stomach (gastric volvulus), duodenum, small intestine, or in any segment of the colon. Gastrointestinal content in the area of the obstruction cannot move in the lumen due to obstruction, and the patient may complain of nausea and vomiting. Vomiting content changes according to the concentration of obstruction. If the obstruction is in the middle of the small intestine, bilious vomiting occurs. If the obstruction is in the more distal part, ileal content comes with vomiting. The situation is different in colon obstruction. If the ileocecal valve function is normal, the material proximal to the obstruction in the colon does not pass the ileocecal valve and a closed-loop occurs; the cecum is stretched and cecal perforation may even develop. If the ileocecal valve loses its function, it can allow the content of colon to pass through the terminal ileum and vomiting becomes fecaloid. Gas and stool output do not occur in mechanical intestinal obstruction, because gas and stool do not pass to distal from the obstruction. However, the discharge of the remaining gas and stool in the distal of obstruction via anal route should not mislead the doctor. The obstruction concentration is recognizable by direct abdominal X-ray in the standing position. If intestinal gas is observed proximal to the obstruction and gas is not observed in the colon, it can be said that the concentration of obstruction is in the small intestine. If gas of colon and haustra of colon are significant proximal to the obstruction, the obstruction concentration has been detected in the colon. CT and MRI are helpful in the diagnosis of obstruction. Intestinal contents accumulate due to intestinal movements near the obstruction and it is detected as the segments of intestine are dilated, the bowel wall is edematous, and the diameter of the intestinal lumen increases. The etiology of mechanical intestinal obstruction varies. This obstruction may be causes by a tumor, intraluminal foreign bodies (bezoar, gallstones), or adhesions developed due to previous operations. Mechanical intestinal obstruction that occurs due to adhesions can be treated with medical treatments. Decompression with a nasogastric tube and parenteral fluid support are used in medical treatment. An obstruction with an intraluminal foreign body usually develops in the narrowest parts of the gastrointestinal tract.

Terminal ileum and sigmoid colon are the narrowest points. If passage does not occur spontaneously, ischemia in the intestinal wall may develop as a result of pressure of the foreign body against the intestinal wall and this may result in perforation. Treatment usually involves surgery. Surgical treatment may be first in tumoral obstructions, as the lumen obstruction develops as a result of tumor growth. In sigmoid volvulus, the sigmoid colon constitutes a closed-loop by turning around its mesentery and can be recognized by its specific appearance on direct abdominal X-ray in the standing position. Colonoscopy is recommended for the reduction of sigmoid volvulus. If this is not successful, early surgical treatment is recommended. Oral laxative drugs given before colonoscopic examination may lead to perforation in patients with obstruction as they increase the pressure in the segments proximal to the obstruction by increasing the severity of the symptoms. This may make vomiting worse, thus increasing complication risk. For this reason, oral laxatives should not be given to patients in whom obstruction is considered. Rectum and sigmoid colon cleansing can be done with enema given rectally. If the obstruction is in the rectum or sigmoid colon segment, rectosigmoidoscopy may be performed to reveal the etiology after enema administered rectally to clean the distal part of the obstruction [258–263].

Refusal of the Process by the Patient

If the patient does not consent, colonoscopy cannot performed for the patient as the application of any process without permission of the patient is not legally possible. Detailed information regarding the process should be provided and explained to the patient so the patient can understand the importance of the procedure. The consequences of not undergoing the procedure should be explained clearly to the patient if he or she does not consent to the procedure.

Toxic Megacolon

Toxic megacolon may appear in various forms of colonic inflammation and especially may be seen in ulcerative colitis. Etiologic factors include inflammatory causes (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, Behcet’s disease), infectious causes (C. difficile, salmonella, shigella), ischemia, and other reasons (collagenous colitis, chemotherapy). Colonic dilatation (>6 cm), submucosal edema, disturbance or loss of colonic haustration, air-fluid concentrations, wall thickening, perforation, and septic thrombosis in the portal system may occur. Early diagnosis and early treatment are important. Total colonoscopy is contraindicated in acute toxic megacolon because of the risk of perforation. Flexible sigmoidoscopy may be done very carefully with minimal air insufflation in order to elucidate the etiology. Cytomegalovirus or pseudomembranous colitis may be explored as etiologic factors by sigmoidoscopy. Diagnostic flexible sigmoidoscopy has a high risk of perforation. In one study, flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed for diagnostic purposes on three patients with toxic megacolon and colon perforation occurred in one patient [248, 264–266].

Fulminant Colitis

Fulminant colitis is severe acute inflammation of the colon with the signs of systemic toxicity. The term acute severe colitis is also used. Colonic dilatation is usually seen. It may be observed in inflammatory bowel disease. Furthermore, it can also be seen in infectious, amebic, and ischemic colitis. Colonoscopy is accepted as a contraindication. However, a few colonoscopy studies performed by experienced endoscopists are available and high risk of perforation is present. If colonoscopy must be done, plain abdominal graphy should be performed before colonoscopy in order to understand whether there was a perforation and plain abdominal graphy should be repeated after colonoscopy for the control. Usually, polyethylene glycol is used for gut lavage. It must be done carefully and with minimal insufflation. Pancolonoscopy is usually not necessary and colonoscopy may be terminated when it approaches the distal part of a severe lesion. Colonoscopy has a high risk of perforation in fulminant colitis. As a result, today, it still “cannot be recommended for general use” [267, 268].

The Patient Who Gives Consent But Is Noncooperative and Cannot Be Adequately Sedated for a Colonoscopy

Patients may give consent for colonoscopy. However, if the patient is noncooperative and cannot be adequately sedated for a colonoscopy, colonoscopy may lead to unwanted complications.

Relative Contraindications

Bleeding Disorders, Thrombocytopenia, Platelet Dysfunction

Colonoscopy is an invasive diagnostic and therapeutic method. During colonoscopy, mucosal laceration, erosion, and ulceration may develop as complications. Polypectomy or biopsy are performed on the polyps or tumors encountered during colonoscopy. The hemostasis system of the body should work correctly and be able to prevent possible bleeding to avoid bleeding after these processes.

A brief review is provided here of the clotting mechanism resulting when bleeding occurs. Endothelial mediators create vasoconstriction when vascular damage occurs. This creates the vascular phase of hemostasis. The next phase is called the platelet phase (primary phase). Platelets come as a result of vascular damage and form a platelet plug by adhering to each other. Tissue factor resulting from the vascular damage activates plasma factors, which leads to fibrin formation and more intact platelet plug. This phase is called plasma phase (secondary phase). Clotting factors become active by intrinsic and extrinsic ways in the secondary phase of hemostasis. Tissue factor is released from the damaged tissue or vessel area. The coagulation path initiated by Factor VII with the help of Ca ++ by binding to tissue factor constitutes the extraintrinsic way and will activate the X Factor. The path initiated by activation of F XII by PK (prekallikrein)/HMWK (high molecular weight kininogen)-kininogen constitutes the intrinsic path. Common pathway develops by activation of Factor X, and prothrombin is converted to thrombin and fibrinogen is converted to fibrin in the common pathway.

Tests Related to the Coagulation System:

Bleeding time: Measures primary hemostasis.

Coagulation time: Measures the intrinsic coagulation pathway. It is prolonged in the presence of “heavy” deficiencies of clotting factors related to the intrinsic system (I, II, V, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII), heparin therapy, and anticoagulants that are circulating rarely.

Activated partial thromboplastin time: A test that reflects the intrinsic coagulation system. It is prolonged with the deficiencies of prekallikrein, high molecular weight kininogen (HMWK), Factors VIII, IX, XI, XII, Factor X, V, prothrombin, and fibrinogen. It is prolonged with the effect of systemic anticoagulants such as heparin.

Prothrombin time: A test that measures the extrinsic coagulation system. It is measured as prolonged in the deficiencies of Factors II, V, VII, X, and fibrinogen. Coumadin shows its effect by inactivating the vitamin K reductase enzyme, which plays a role in the formation of Factors II, VII, IX and X. Warfarin reduces the activity of these factors while consuming vitamin K.

Thrombin time: A test reflecting the converting reaction of fibrinogen to fibrin by thrombin.

Fibrinogen/fibrin degradation products (FDP): FDP increases in serum as a result of primary fibrinolysis and secondary fibrinolysis resulting from widespread intravascular coagulation.

D-dimer test: Specifically, it shows the presence of fibrin degradation products, namely the cleavage products containing crosslinks. It does not indicate the fibrinogen degradation products. Increase in D-dimer values is observed in secondary fibrinolysis, venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. In addition, D-dimer increases in cases such as major surgery, malignant tumors, bleeding, and sepsis.

Bleeding, which can occur during colonoscopy, may be a problem in low platelet count or normal platelet count when using drugs such as aspirin that disrupt normal platelet function and coagulation dysfunction. Taking a detailed history from the patient and performing routine tests administered for coagulation will prevent possible bleeding complications [269–275].

Neutropenia

If absolute neutrophil count is <1,500 cells/mm3, it is called neutropenia. The counts are 1,000–1,500 cells/mm3, 500–1,000 cells/mm3, and <500 cells/m3 in mild, moderate, and severe neutropenia, respectively. Neutropenia occurs as a result of a lack of bone marrow production, sequestration of neutrophils, or increased destruction of neutrophils. Neutropenia can be congenital or acquired. Neutrophils protect against bacterial and fungal infections [276, 277].

Neutropenia constitutes a susceptibility to infection. Colonoscopy is relatively contraindicated in the presence of neutropenia. The incidence of bacteremia during colonoscopy varies from 2 to 4 %. Therefore, antibiotic prophylaxis should be performed in neutropenic patients if colonoscopy will be performed [278, 279].

Ischemia, necrosis, perforation, sepsis, and multiorgan failure may develop in typhlitis and neutropenic enterocolitis. Neutropenia after chemotherapy is followed by typhlitis; it is usually seen in myelo-suppressed patients and is a transmural inflammation localized at the cecum. In neutropenic enterocolitis, inflammatory symptoms in other regions (terminal ileum and other segments of the colon) are observed with neutropenia. Increase in intestinal wall thickness, fever, abdominal pain, and diarrhea exist in typhilitis and neutropenic enterocolitis. Colonoscopy is contraindicated due to the high risk of perforation. Radiological imaging modalities (plain graphy, ultrasound, CT) are helpful for the diagnosis. Medical treatment is applied, and surgical consultation should be requested when complications develop [280, 281].

Previous Intestinal Surgery

Wound healing is divided into three linked phases:

(a)

Hemostasis and inflammation: This phase lasts the first 3 days. Hemostasis occurs and inflammatory materials accumulate. This period can be divided into periods dominated by platelets, granulocytes, and macrophages.

(b)

Proliferation: This period lasts 3 weeks. In this phase, fibroblasts and epithelial and endothelial cells are enabled. New capillaries are formed. Collagen accumulation is seen in the wound.

(c)

Maturation and remodeling: This phase lasts up to 6 months. Scar tissue begins to develop. Tensile strength further increases.

The mechanical strength of a colon anastomosis is 45 % of normal tissue on the 14th day and reaches the concentration of 75 % in the fourth month [282].

Colon anastomosis after colon resection can be performed at any concentration. The strength of the anastomosis is weak in the early period and colonoscopy can lead to perforation of the anastomosis. Therefore, it is generally contraindicated.

Patients at Risk of Intestinal Perforation (Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Marfan Syndrome)

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS)

EDS is an inherited connective tissue disease. The clinical triad is articular hypermobility, dermal extensibility, and cutaneous scarring. Clinical features include hypermobility in joints, hyperelasticity of the skin, tissue fragility, delayed healing of wounds, and easy bruising [283, 284].

Subtypes of EDS

EDS type 1 and type 2: Hyperextensibility of skin, widened atrophic scarring, and hypermobility of joints are seen as major findings. Minor symptoms include easy bruising, smooth and velvety skin, molluscoid pseudotumors, subcutaneous spheroids, muscular hypotonia, complications of joint hypermobility, surgical complications, and positive family history. The former EDS type I and type II are now reclassified as EDS, classic type. It is an autosomal dominant inherited disease [285–287].

EDS type 3: Hypermobility type. In this form, joint hypermobility is the primary manifestation. Subluxation or dislocation is common and this situation develops spontaneously or with minimal trauma as painless. It is an autosomal dominant inherited disease [286, 287].

EDS type 4: Vascular type. There are four clinical criteria: easy bruising, thin skin with visible veins, characteristic facial features, and rupture of arteries, uterus, or intestines. It is autosomal dominant. Spontaneous nontraumatic, nonaneurismatic aortic rupture can be seen [287–289].

EDS type 5: This type has similar clinical characteristics with Type 2. Biochemical defects are poorly understood. It is an X-linked recessive disease [287].

EDS type 6: Kyphoscoliotic type. It is characterized by kyphoscioliosis, joint laxity, and muscular hypotonia. In some cases, fragility of ocular globe may be seen [286].

EDS type 7A ve 7B: Arthrochalasia type: Severe joint hypermobility at birth and congenital bilateral hip dislocation are seen [286].

EDS type 7C: Dermatosparaxis type: Extreme fragility of the skin and skin laxity are present [286].

EDS type 8: Periodontal type: Hyperelastic fragile skin, moderate joint hypermobility, and severe periodontitis are seen. It is an autosomal dominant inherited disease [287].

EDS type 9: Occipital horn syndrome: Wedge-shaped calcifications are observed at the place where the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles adhere to the occipital bone [286].

EDS type 10: Similar to EDS type 2, with abnormal clotting studies. It is an autosomal recessive disease [287].

Spontaneous intestinal perforation is also seen in EDS. The sigmoid colon is the most common location where perforation is seen. It is also seen in other places (small intestine, stomach). In one study, resection and end-to end anastomosis and colostomy were performed. Total colectomy was performed for recurrent perforations [288].

In Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, colonoscopy is relatively contraindicated as there is high risk of colon perforation. In addition, the danger of spontaneous aortic rupture in EDS type 4 should not be forgotten.

Marfan Syndrome

Marfan syndrome is an autosomal dominant inherited disease. The mutation in the FBN1 gene encoding fibrillin 1 is responsible for Marfan syndrome. It is a multisystem connective tissue disease and often affects the cardiovascular system; aortic dissection and aortic dilatation are frequently seen [290, 291]. The cardinal symptoms include ocular, skeletal, and cardiovascular system symptoms. Ectopia lentis, as a finding of the eye, has an important place in the clinical signs [292, 293].

Ghent nosology is used in the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome. In diagnostic Ghent nosology, the skeletal system, ocular system, cardiovascular system, pulmonary system, skin/integument, dura, and genetic findings are assessed. While findings such as pectus carinatum/pectus excavatum, scoliosis, pes planus, joint hypermobility, and characteristic face findings are seen as the symptoms in the skeletal system, lens dislocation is among the ocular findings. Lumbosacral dural ectasia takes place in dura pathologies. Spontaneous pneumothorax is seen in 4–11 % of patients with Marfan syndrome [294].

Relative colonoscopy is contraindicated in Marfan syndrome. Reports of spontaneous aortic rupture that can occur rarely after colonoscopy are available in the literature [289].

Acute Diverticulitis

Acute diverticulitis is a disease of the diverticula in colon caused by infection. Diverticula may be in any segment of the colon but are seen mostly in the sigmoid colon. Transition regions of the vessels in the colon wall are weak places and intraluminal pressure elevation takes place in the etiologic factors of formation of diverticulum. Diverticulitis is among the complications of diverticulum. In diverticulitis, bacterial infection occurs. The infection may remain local or may become transmural. Colon wall edema, erythema, and fragility occur in diverticulitis. The severity of abdominal pain in patients gradually increases. Perforation may occur in diverticulitis and localized peritonitis may develop; if the infection spreads, it may take the form of generalized peritonitis. The gas inside the colon passes through the intraperitoneal area. Depending on the severity of perforation of diverticulitis, intra-abdominal free air may be observed as subdiaphragmatic free air in direct abdominal X-ray in the standing position. The complaints of fever may also be evident. If the perforation remains localized, localized abscess may develop in this region, swelling, redness, and edema in the skin may be seen in the left side of the abdomen. In abdominal examination, defense, rebound, and tenderness in the left lower quadrant are observed.

Laboratory methods can be utilized for diagnosis. Leukocytosis is evident. Localized intra-abdominal fluid, abscess, and edema in the tissue can be determined with abdominal ultrasonography. Abdominal computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are sensitive in the diagnosis.

The treatment is medical therapy in patients without complications. Colon rest and antibiotic treatment are recommended. Surgical treatment is performed for the patients in whom complications develop. Draining of the abscess and resection of the perforated area are among the treatment options. Temporary colostomy can be opened after resection.

Previous Cardiac Infarction and Pulmonary Embolism

Postoperative Condition from Recent Surgery

Abdominal surgeries may be open or laparoscopic. In open surgery, the abdomen may be entered with a midline, subcostal, transverse, or other special type of incisions. The incision is closed in accordance with the anatomical layers at the end of the operation. The risk of eventration and evisceration is present for each incision line closed.

Thoracic incisions are made in the midline with sternotomy or as thoracotomy in the lateral wall of thorax. Thoracotomy is done in the intercostal line; rib resection can be performed from this incision. Gynecological incisions may be below the umbilicus in the midline abdomen as well as in the form of transverse incisions at the lower abdomen. Various incisions in other branches of surgery are also possible (such as craniotomy, orthopedic surgery incisions).

In colonoscopy, the colon is distended due to introduction of air into the colon, intra-abdominal pressure increases, and abdominal distention may occur. This situation can lead to stretching of abdominal incisions. In addition, colonoscopy, which is performed during the recovery period, may lead to discomfort in patients who have been newly operated. In such patients, colonoscopy is relatively contraindicated [19].

Very Large or Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Abdominal aortic aneurysm accounts for 1–3 % of deaths in developed countries among men ages 60–85. It is typically asymptomatic. It is determined during radiological investigations required for other reasons. Tobacco use, hypertension, family history, male sex are among the risk factors. Aneurysm is a permanent focal dilatation 1.5 times more than the normal diameter of the artery. Normally, infrarenal aortic diameter is 1.5 cm in women older than 50 years, and 1.7 cm in men older than 50 years. If infrarenal aortic diameter is 3 cm or more, it is accepted as aneurysm [299, 300].

Palpable pulsatile mass is felt in the abdomen in the examination for the diagnosis. Imaging modalities, ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging are accurate in diagnosis [301].

The research reports that abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) may be associated with colorectal cancer at an increased frequency. In a study by Veraldi et al., the association of abdominal aortic aneurysm and colorectal cancer is mentioned in 14 patients [302].

Colonoscopy is relatively contraindicated in AAA. Blood pressure may rise during colonoscopy. Stress can occur. Rupture may be seen in AAA, which can have fatal consequences. However, the relative contraindication should not lead to overlooking colon cancer.

Instruments and the Colonoscopy Room

Properties of the Colonoscopy Unit

The endoscopy unit is where endoscopic diagnosis and treatment are performed; it requires teamwork to operate this unit. At the entrance to the endoscopy unit, the reception, registration, and waiting room should be found. After the waiting room, there should be a place for the patients to change clothes before entering for endoscopic procedures. After changing clothes, patients are taken to the preparation area to be prepared for endoscopic procedures. An intravenous route is opened. Patients are then taken into the endoscopy room and endoscopic procedures are performed. Two hundred to three hundred square feet is usually sufficient for an endoscopic procedure room (Fig. 5.1). Here, the patient should be sedated by the anesthesiologist and monitored while endoscopic procedures are performed. In the recovery room (Fig. 5.2), patients rest and resolve toilet needs after endoscopy. The patients, who change their clothes in patients’ dressing room, are discharged with advice and arrangements of their treatment. In the unit, there should be a secretary and medical staff helping the endoscopist.

Fig. 5.1

Endoscopic procedure room

Fig. 5.2

Recovery room

The equipment that should be found in the unit include toilet, sink, examination tables, intravenous equipment and solutions, aspirator for oropharyngeal suction, medical drugs (analgesic, sedatives, anticholinergics, narcotic and benzodiazepine antagonists, emergency cardiac medications), resuscitation devices (laryngoscopes, Ambu bag, endotracheal airway, cardiac monitor, defibrillator, resuscitative medications), endoscopes and endoscopy set, electrocautery, and endoscopic accessories.

All surfaces of the endoscopy unit should be easy to clean and have disinfectable features. A sink should be found in the room where the endoscopy procedure is performed. There should modern and adequate toilets that can respond to the needs of the unit and lockers where patients can put their clothes. An oxygen and suction system should be present, along with a pulse oximetry device, blood pressure gauges, and an ECG device. In the unit, there should be a room reserved for the disinfection process (Fig. 5.3). Endoscope disinfection procedures should be performed. Endoscopic procedures should be able to be recorded with a video recording system. Temperature of refrigerators where medications and kits are stored should be monitored. An emergency response kit must be kept in the endoscopy unit. There must be an appropriate waste container for medical waste.

Fig. 5.3

Disinfection process room

Complications may develop during a colonoscopy procedure and emergency surgery may be required. Therefore, the doors the endoscopy unit must be adequate in size to allow the passage of a stretcher. The transport pathway must be short and wide enough to avoid difficulties in the transport of a patient from the unit to the operating room. If the endoscopy unit is outside the hospital, the patient can be transported to the hospital by ambulance. In this case, access of a patient stretcher through doors and elevators and onto an ambulance from the endoscopy unit is very important [303–305].

Presentation of Colonoscopy Instruments

Today, modern endoscopic devices are used. Colonoscopy images can be watched on screen in high-definition (HD) quality and video recordings can be made. Images and video recordings can be given to patients on CD or DVD.

Colonoscopy can be managed with the head of the control colonoscope. The tip of the colonoscope can be angled up and down and left to right. The viewing angle of the colonoscopy instrument is 170°. The colonoscope has a small number of channels, which provide water or air and aspiration. Moreover, the cannulae and accessory instrument entries are made through these channels. The instrument channel is about 3.2 mm. The light source and microcamera are located in the tip of the video-colonoscope and the image is delivered to the screen with this camera. The approximate length of the colonoscope is 170 cm and the shaft diameter can vary between 12 and 13 mm. Many companies produce colonoscopes and different features can be found in each [306, 307].

Patient Preparation for Colonoscopy

During colonoscopy, the inner surface of the colon should be clean and not covered with stool and fluid; all mucosa should be seen clearly. If the inner surface of colon is dirty, the oral laxatives given have not been cleared, or the inner surface of the colon cannot be displayed due to fluid accumulation, the colonoscopic examination will not be satisfactory and should be performed again. Hence, the full preparation of the patient before colonoscopic examination is important. Patients should be evaluated in terms of cardiac and lung problems prior to colonoscopy and possible problems should be resolved. Bleeding or clotting problems should be corrected if present. Dietary recommendations can be made before the colonoscopy. Prepackaged meals for a low-residue diet are commercially available [308].

The three types of diet are as follows:

1.

Clear Liquid Diet (CLD): No solid food is given in this diet. Milk and fruit juices containing pulps are also not given.

2.

Low-Fiber Diet (LFD): This is a modification of a normal diet, however, fiber cannot exceed 10–15 g/day.

3.

Low-Residue Diet (LRD): This diet includes a low fiber diet. Prune juice is not given and milk is allowed a maximum of two times per day [309].

Some researchers suggest a low-residue diet for two days prior to colonoscopy, others suggest one or 3 days [310]. In many endoscopy centers in Turkey, the diet without pulp is recommended. It allows fluids such as water, tea, lime, herbal tea, clear compote juice, filtered meat and chicken broth, juice of soup made with meat and noodles, cherry juice, apple juice, sodas, and water with sugar. Jam and honey are also allowed as they do not contain fiber. Cherry juice and apple juice are recommended because they do not contain pulp. Peach juice is not recommended as it is pulpy. These suggestions are not for diabetic patients. In diabetic patients, this regimen can cause a rise in blood sugar. Sugar-free fluids are recommended for diabetic patients [311–313]. A diet list is usually given to patients by the colonoscopy center. Patients are advised to comply with this list. Poorly absorbable materials are used for intestinal cleaning. Polyethylene glycol (PEG), sodium phosphate, or magnesium citrate are the ones most commonly used. Isosmotic preparations contain PEG. These preparations cause minimal water and electrolyte secretion into and absorption from the intestinal lumen. The standard dose is 240 ml of 4L PEG-ELS (polyethylene glycol-electrolyte lavage solutions) every 10 min or 20–30 ml/min. There are some preparations that reduce the volume of PEG-ELS by combining it with bisacodyl. NaP is a hyperosmotic intestinal preparation that shows its effect by attracting water and electrolytes into the lumen of the intestine. Magnesium citrate is another hyperosmotic agent and has a stimulating effect on intestinal peristalsis [308, 314, 315].

Oral mechanical intestinal cleansing drugs may create abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting in patients. Diarrhea occurs due to mechanical intestinal cleansing. This results in a loss of fluid. Patients should drink water or liquid to offset the loss of fluid, otherwise hypotension, tachycardia, and a decreased amount of urine may occur. Parenteral fluid replacement may be required for patients who cannot receive oral liquid. For patients who cannot tolerate oral cleansing, intestinal cleansing should be performed in the hospital. Generally, an enema is recommended before the colonoscopy. If enema is performed 1–2 h before the colonoscopy, it will give the patient adequate time for defecation and preparation for the colonoscopy. The need for defecation should be eliminated prior to colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy Techniques and Position Maneuvers

After the patient has completed the process of intestinal cleansing and has changed clothes, they enter the room where the colonoscopy will be performed. An intravenous route is opened and the patient is monitored. The patient lies on a stretcher in the proper position for a colonoscopy. In the recumbent position, the patient lies on the left side, turning their back to the endoscopist and pulling their legs toward their abdomen. The elevation of the stretcher is determined by the endoscopist. The colonoscopy procedure begins with inspection of the anal region. Perianal fistulas in the anal region, anal fissure (chronic or acute), and the presence of hemorrhoids are investigated. Hemorrhoids are classified as internal or external: those above the dentate line are internal, those below the dentate line are external. It should be noted that hemorrhoids develop as a result of collateral circulation due to portal hypertension [316].

Anal fissure is painful. The nerve endings are at an easy inducible state because mucosal integrity is impaired in the base of fissure. In these patients, local anesthetic spray (lidocaine) for fissure prior to colonoscopy is applied in our own endoscopy units to reduce pain and improve the patient’s comfort.

After inspection of the anal region, digital examination of the anal canal and distal rectum is performed. With digital rectal examination, the characteristics of rectal wall are investigated and any occlusion of the lumen or the presence of a tumoral mass are noted. If the colonoscope is inserted through the anus without direct digital rectal examination, complications may develop in the presence of obstructing masses in the lumen. The colonoscopy instrument is inserted into the anus after digital rectal examination and the lumen begins inflating due to introduction of air; images are the taken.

The rectum extends from the anal canal to the promontorium and is approximately 12–16 cm in length. There is no haustra in the rectum. In the inner surface of the rectum, there are three valves formed by the rectal mucosa folds, which are called the valves of Houston. The top and bottom valves are located on the left; the middle valve is located on the right. The middle valve (Kohlrausch’s plica) is accepted to be located at the concentration of the anterior peritoneal reflection. Biopsy can easily be obtained because the valves are formed only with mucosa and the risk of perforation is very low. The rectal part under the middle valve is larger than the upper part; therefore, it is called the ampulla recti. The rectum is conventionally divided into three parts as the upper third, middle third, and lower third, and, in practice, each is considered to be 5 cm in length. The upper third of the rectum is anteriorly and laterally invested by peritoneum. The middle third of the rectum is only anteriorly invested by peritoneum. The lower third of the rectum is totally extraperitoneal [317–319].

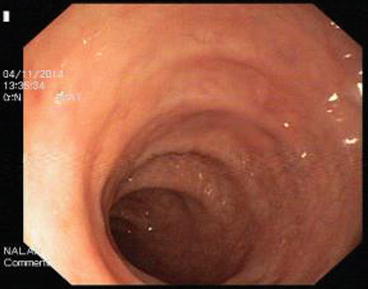

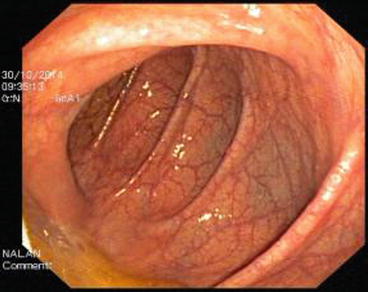

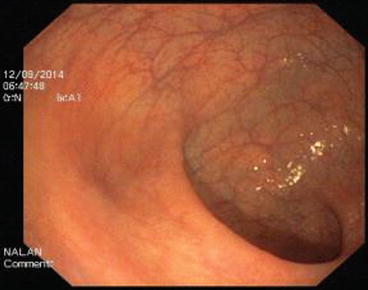

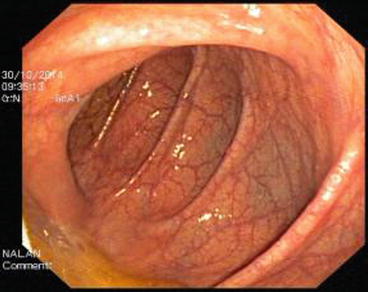

After passing through the rectum (Fig. 5.4) with the colonoscope, the sigmoid colon (Fig. 5.5) limit is reached in the sacral promontorium. Passing the rectosigmoid junction may be problematic, and it should be passed patiently. The rectosigmoid junction is a narrow and sharply angulated segment, making endoscopic recognition easy. The inner surface of the sigmoid colon varies from the rectum endoscopically. The sigmoid colon is approximately 35–40 cm in length and all sides are covered with peritoneum. It is located intraperitoneally and is mobile. Length can vary. There are haustras in the sigmoid colon. The haustras in the distal sigmoid colon are completely deleted. The sigmoid colon is the narrowest part of the colon and the narrowest point is reported to be 2.5 cm [319–322].

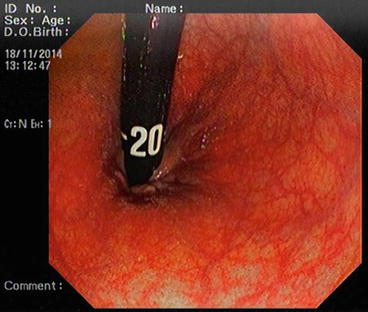

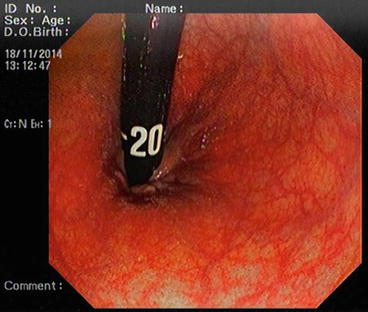

Fig. 5.4

Rectum

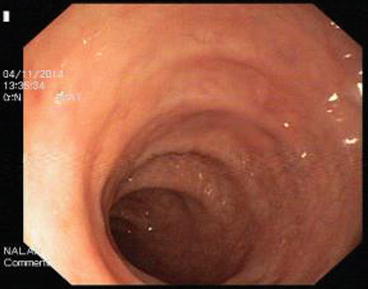

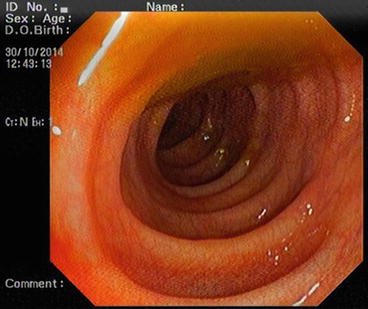

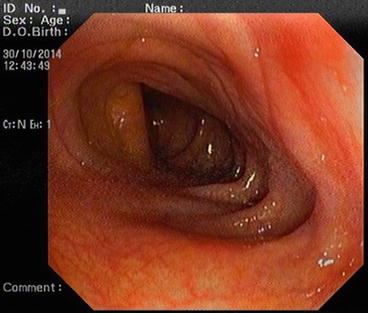

Fig. 5.5

Sigmoid colon

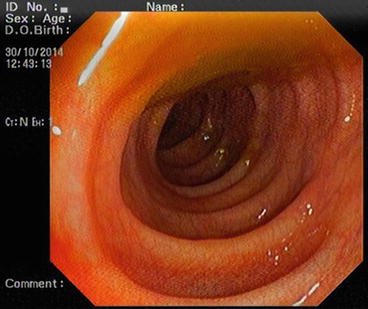

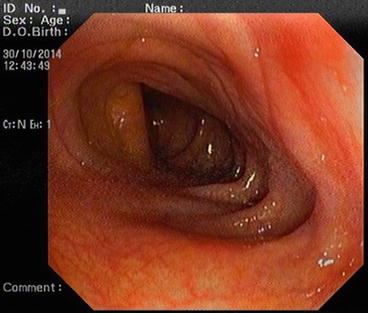

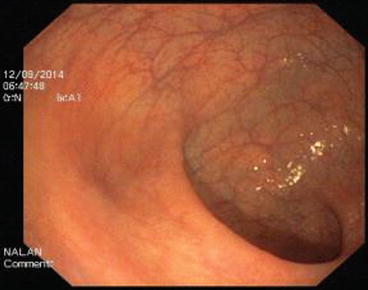

The descending colon (Fig. 5.6) is adherent to the retroperitoneal tissue. The air-liquid surfaces are seen in the left descending colon lumen during colonoscopy because the patient lies on the left side. The splenic flexure (Fig. 5.7) is the junction of transverse colon and descending colon. This may present difficulties in terms of the transition with colonoscopy and patience is required. The spleen can be recognized as a shadow from the colon wall at the splenic flexure (Fig. 5.8). The splenic flexure is under the left costal margin. The transverse colon (Fig. 5.9) is approximately 45 cm long and the lumen is seen as a triangular configuration. It is invested with peritoneum in the abdomen and is mobile. The liver tissue (Fig. 5.10) may be noticed from the wall of colon when the hepatic flexure is passed. The hepatic flexure is close to the liver and localized in the right upper quadrant. In 90 % of cases, the ascending colon (Fig. 5.11) is located retroperitoneally. The approximate length of the ascending colon is about 25 cm. The cecum (Fig. 5.12) is the widest part of the colon and localized in the right iliac fossa. Three tenia coli converge at the base of the appendix; the inside of the cecum is thus seen endoscopically as a tri-radiate fold (“Mercedes-Benz” symbol, crow’s foot). The appendix orifice may not be recognized because it is unclear. The ileocecal valve has upper and lower lips (Bauhin’s valve). The terminal ileum (Fig. 5.13) is entered from here [10, 319, 323, 324].

Fig. 5.6

Descending colon

Fig. 5.7

Splenic flexure

Fig. 5.8

Splenic shadow

Fig. 5.9

Transverse colon

Fig. 5.10

Liver shadow in hepatic flexure

Fig. 5.11

Ascending colon

Fig. 5.12

Cecum

Fig. 5.13

Terminal ileum

A basic rule in colonoscopy is that, if the lumen is not seen clearly and there is any resistance, the colonoscope should not be forwarded. If there is doubt, the colonoscope should be withdrawn. It should be worked with the minimum air required; more air than necessary should not be introduced into the colon. Attention should be given to the patient’s pain reactions [10].

During colonoscopy, patients are positioned lying on their left side. The entire colonoscopy usually can be completed in this position. Some patients may need the supine position after the start of the colonoscopy. This position allows external compression and splinting (especially for the transverse and sigmoid colon). The supine, right lateral position may be necessary while passing problematic regions (rectosigmoid junction, splenic flexure, hepatic flexure, intubation of the ileocecal valve). The colonoscope may create looping or bowing because the sigmoid colon is mobile. In this case, it may be difficult to pass the sigmoid colon, and even if it is passed, progress of colonoscope may not be achieved.

Various maneuvers are performed to correct the position of the colonoscope. The colonoscope is pulled back and air inside the colon is aspirated. This may help with moving the colonoscope forward. If this maneuver does not help, auxiliary staff applies gently pressure (external hand pressure) on the abdomen to fix the colonoscope, and bowing can be corrected. This abdominal pressure can be made nonspecifically or can be done for the specific abdominal regions. The alpha-loop maneuver may also be tried to pass the sigmoid colon. For this, the endoscope is pulled back for 25 cm, the straightening of sigmoid colon is made, and clockwise rotation is done for the colonoscope shaft. Fluoroscopy also can be utilized to determine the position of the colonoscope. The colonoscope should be advanced by seeing it on the screen. However, if the lumen is obstructed or it cannot be advanced due to sharp angling, the colonoscope may be advanced gently by an experienced endoscopist to find the lumen. This maneuver is dangerous and should be performed only by experienced endoscopists. If the mucosa is discolored, whitened, and mucosal vessels become invisible, or if the patient has significant pain during this movement, this procedure should be abandoned and the colonoscope should be pulled back slightly. We emphasize that this maneuver is dangerous and may lead to perforation and thus should be avoided whenever possible. Blind insertion should not be done in diverticular disease. After passing the splenic flexure, a loop can occur in the redundant transverse colon down toward the pelvis. Hooking the tip and withdrawal of colonoscope or changing the position of the patient may correct the formation of a loop in the transverse colon. While passing the hepatic flexure, placing the patient in the supine or right lateral position may help. During colonoscopy, it is recommended to make video recordings of the segments of colon. If this cannot be done, then photos of the segments of colon must be taken. When the cecum is reached, photos of the cecum should be taken due to medicolegal reasons [324–327].

Some researchers believe that the water immersion technique is an alternative colonoscopy technique, an report that the cecum is more easily reached [328]. Total colonoscopy, even in experienced hands, cannot be completed in up to 10 % of patients. In such cases, some imaging techniques have been developed. One of these methods is the single-balloon-assisted colonoscopy. The colonoscope with an overtube balloon and balloon control unit is used. In the application technique, the colonoscope is inserted through the anus and forwarded, then the deflated overtube balloon is moved inward via colonoscope and inflated. The colonoscope is forwarded further, the overtube balloon is deflated and forwarded via colonoscope and reinflated. The process is performed in the form of repetitive movements in this manner [329, 330].

The colonoscope is pulled back after the colonoscopy process is completed. The aspiration of gas of colon when the colonoscope is pulled back may lead the reduction of gas distention and contribute to the comfort of the patient. The colon surface should be observed carefully while exiting in order to avoid overlooked lesions. When the rectum is reached, the inner surface of the rectum should be observed by making a retroflexion in the ampulla recti.

Colonoscopy Complications

Colonoscopy complications may be related directly to the process of colonoscopy as well as the other systems in our body that are affected during colonoscopy (hypertension, cardiac problems, etc.). Perforation, splenic trauma, bacteremia, severe abdominal distention, bleeding, missed adenomas, and incomplete removal of neoplasia can be associated with colonoscopy [331, 332]. These complications are examined in detail below.

Perforation

Colonic perforation occurs in 0.2 % of colonoscopies in the diagnostic process and 0.5–3 % in the therapeutic process. Some segments of the colon are intraperitoneal and some segments are extraperitoneal. For example, the lower third of the rectum is extraperitoneal. The back side of the descending colon is retroperitoneal and this side is not covered by peritoneum. Clinical symptoms and signs vary depending on whether the perforated surface of the colon is intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal. In extraperitoneal perforation, soft tissue infection, inflammation, and abscess formation are observed, depending on the features of the location of perforation. This abscess can be forwarded along tissue planes. Sometimes, symptoms such as erythema, temperature rise in the skin, and sensitivity may occur. In extraperitoneal rectal perforation, pelvic infection, localized air between soft tissue planes, perirectal abscess formation, and clinical manifestations in the perianal region may occur due to perforation and perianal abscess may be seen. Perianal abscess can be drained from here. Rectal perforation may occur during the entry of the endoscope. This is seen more frequently in rigid rectosigmoidoscopy. Rectal perforation may develop in the rectum during retroflexion of colonoscope. If early diagnosis cannot be made and treatment is delayed, septicemia and death may result. In perforation occurring in the extraperitoneal walls of the descending and ascending colons, back pain, pain at the sides of the abdomen, abdominal pain, detection of hematuria and leukocytes in the urine sediment with the involvement of ureter in the inflammation, chills, fever, localized abscess, retroperitoneal air, skin redness, warmth, swelling, and tenderness with the advancement of abscess may be present according to the location properties of the perforations.

Perforation may be recognized during endoscopic procedures. If it is not diagnosed during the endoscopic procedure, the possibility of perforation should be remembered upon improvement of the patient’s complaints after the colonoscopic procedure and further investigations should be carried out. Ultrasonography can show localized abscess formations. The tissue planes are displayed better with the methods of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen, and tissue inflammation, localized free air, and abscess formation can be determined. Symptoms vary in perforations occurring in the wall of colon covered with peritoneum. A portion of air given into the colon during colonoscopy passes into the peritoneal cavity in intraperitoneal perforations. This air accumulates in the subdiaphragmatic region and appears as subdiaphragmatic free air in the direct abdominal X-ray in the standing position. The signs of abdominal pain and peritoneal irritation develop with the passage of intestinal contents into the peritoneum from the site of perforation. Muscular defense and rebound tenderness are determined in the examination. Bacterial peritonitis occurs due to colonic contents. Fever is detected in addition to abdominal pain. Symptoms of sepsis, multiorgan failure, and death develop in untreated patients. Early diagnosis and treatment are very important. Fluid can be detected by abdominal ultrasonography in the abdomen. Intraperitoneal free air and fluid are determined with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. It is possible to detect leukocytosis and an increase in sedimentation rate in the blood tests. Termination of oral feeding, switching to parenteral nutrition, and broad spectrum antibiotic treatment are necessary in the treatment of perforation, regardless of whether it is intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal. The closure of the perforation is required. The perforation can be closed endoscopically or surgically. Clinical studies on the closure of colon perforation as endoluminal with endoluminal clips have had successful results. In endoscopic clips closure, if the intraperitoneal free air passed into abdomen creates discomfort in the patient, it may be discharged with an ultrasound-guided needle. If localized abscess develops, it may be drained with the help of ultrasound. If a fistula develops, the decision of whether to apply medical or surgical treatment is made according to the daily flow of the fistula and the patient’s general condition. If the perforation site is in the rectum or can be reached comfortably from the anal canal, the perforation site can be sutured from the anal canal. If the perforation requires surgical treatment, this surgical treatment can be done in the form of open or laparoscopic surgery. Surgeon’s experience and preferences and the patient’s condition are factors in this decision. In laparoscopic surgery, the abdomen is entered with trocars and suturing of the perforation, resection and anastomosis, or protective temporary colostomy can be performed. The inside of the abdomen is washed with physiologically tolerable serum, and a tube can be inserted for drainage. The same procedures are carried out in open surgery. Laparoscopic surgery requires special expertise and equipment [333–338].

Splenic Trauma

Splenic trauma may occur during colonoscopy, especially when passing the splenic flexure. The splenic flexure is adjacent to with spleen. If colonoscope is moved without being seen lumen, the tip of colonoscope creates pressure on the splenic tissue and can lead to injury of the spleen. The integrity of spleen is disrupted after splenic injury. Arterial and/or venous bleeding may be seen. Bleeding may be minimal and stop spontaneously or major arterial bleeding and hypovolemic shock may occur in patients and, if it is not treated, may cause death. Left upper quadrant pain develops in patients. The severity of pain varies from person to person. Muscular defense and rebound may be subtle because blood is not irritating to the peritoneum or it may be evident in the late period. Orthostatic hypotension, significant hypotension, or tachycardia may develop according to the severity of bleeding. Imaging methods are helpful in defining the spleen trauma. In ultrasound imaging, determining the integrity of the splenic parenchyma is very important. Splenic capsule, impaired splenic integrity due to perforation, can appear in ultrasound. In addition, the presence of perisplenic fluid is indirect evidence of bleeding. If computed tomography is taken without intravenous contrast substance, the structure of the splenic parenchyma and the integrity of the parenchyma are identified. Intravenous contrast-enhanced CT can determine the presence of active bleeding. Likewise, magnetic resonance imaging may show perforations in the spleen. Arteriography and scintigraphy are also sensitive imaging methods for imaging the active bleeding, but arteriography and scintigraphy are not available in every hospital. However, it is possible to find ultrasonography and even CT in many hospitals.

In the treatment, fluid replacement is started via the intravenous route that was opened prior to colonoscopy. The patient should be hospitalized and monitored, and complete blood count, biochemistry, PTT (partial thromboplastine time), INR (international normalized ratio), bleeding time, and blood group tests should be performed. If possible, the patient should be taken to the intensive care unit. Blood pressure and pulse should be monitored. If the patient’s condition is stable or hypotension or tachycardia are not detected, the patient can be followed by replacement therapy. Fresh blood can be used to replace blood loss during hemorrhage. When fresh blood is not available, erythrocyte suspension (ERT) is given. We give 1 unit of fresh frozen plasma for every 3 ERT suspension as erythrocyte suspensions do not contain platelets and clotting factors. Follow-up tests of platelet concentrations in the blood count should be performed and, if necessary, platelet suspensions should be given. However, if muscular defense and rebound are determined on abdominal examination or decompensation (hypotension and tachycardia) develops in the patient, surgical treatment will be required. Laparotomy may be performed with a midline or left subcostal incision. Splenorrhaphy or partial splenectomy can be performed to save the spleen. If these procedures are not successful, a decision may be made to perform a total splenectomy. A drain is placed and the abdomen is closed. After splenectomy, pneumococcal vaccine to provide immunity against pneumococci should not be forgotten [339–343].

Bacteremia

Bacteremia can be seen in 4.4 % of cases after a colonoscopy. This bacteremia is usually transient and recovers without any sequelae. Infective endocarditis and splenic abscess developing after colonoscopy have been reported in the literature. The symptoms may develop 2 weeks after the colonoscopy. The complaints of splenic abscess may begin with left upper quadrant pain. Imaging techniques such as ultrasonography and computed tomography are useful in diagnosis. In the treatment of splenic abscess, splenectomy may be necessary in addition to parenteral antibiotic therapy [344].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree