College Health

Sarah A. Van Orman

James R. Jacobs

KEY WORDS

College health

College students

Health promotion

Healthy Campus 2020

Medical home

National College Health Assessment

Student affairs

Student health services

More than 21 million students were enrolled in 2010 in the 4,495 colleges and universities in the US, with an anticipated 24 million by 2020. Over half (57%) of these students are in the 14- to 24-year-old age-group. College students comprise almost half the young adult population aged 18 to 24.1 This young adult population comprises a unique population with specific health-related assets and vulnerabilities. While students are generally healthy, mental health conditions, substance use and misuse, injuries, and an increasing number of students with chronic illnesses represent significant health issues. The college campus is a unique health environment that creates risks and opportunities including efficient and effective delivery of health care services as well as opportunities for prevention through health promotion and public health initiatives. Colleges and universities, collectively referred to as institutions of higher education (IHEs), are important settings for the provision of health care as well as preventing or reducing health risks and enhancing well-being among a large portion of the young adult population. Understanding the campus environment and resources is critical when providing care for a college student. As care for college students is often shared between an on-campus student health service (SHS) and a hometown community provider, strong communication and collaboration are required to ensure the best possible care.

On-campus SHSs have as their mission the health and well-being of college students to support student academic success and retention, reduce institutional risk, and create healthier adults in the future. The last available survey data on health services on college campuses in 1988 estimated that there were approximately 1,600 colleges or universities that provide some level of health services, but the current actual number is unknown and likely much larger.2 What specific services are offered varies widely in the US, ranging from part-time nurses providing triage and referral to comprehensive ambulatory health care centers providing medical and mental health care, public health, education and prevention services, and occasionally disability and recreational services.3 Today’s exemplary SHSs provide direct medical and mental health services, undertake population-based initiatives through health promotion and education, and are the public health leaders for their institutions, guiding campus health policy. Their overarching role is to create a healthy and safe campus environment, one that helps make possible the learning, research, and teaching to which the institution is dedicated and which promotes student success. SHSs seek to reduce risk and reinforce behaviors that create health for the individual and for the community. The best practices in college health continually assess the student population on the particular campus to track their health status and identify service needs. This may involve assessing health status and promoting health in students who may never visit the SHS, through population-based primary prevention programs such as mandatory pre-matriculation alcohol education and campus vaccination outreach programs. SHS professionals frequently advise and help shape campus health policies, such as tobacco-free college campuses, and conduct surveillance of and lead responses to public health concerns.

Issues of college health are important to health care professionals serving adolescents and young adults (AYAs) for many reasons, including the following:

Health care providers often perform precollege examinations or provide care during college years.

Health care providers may communicate and collaborate with SHS providers and other student affairs professionals regarding the health care needs of a college student.

SHS providers may be a source of ongoing referrals to other health care professionals of patients needing hospitalization or secondary and tertiary care consultations.

Collaboration among SHS health care providers, other health-care providers, insurance providers, local public health officials, and student affairs professionals can benefit all parties and especially students.

Significant opportunities exist within SHSs for both teaching and research as well as employment and career opportunities.

American College Health Association Benchmark Survey

In 2006 and then again in the spring of 2010, the American College Health Association (ACHA) conducted a survey of campuses nationally regarding the utilization, staffing, and services available at SHSs, the ACHA-SHS Survey. SHSs nationally were invited to participate. While the number of campuses responding was small (N = 172) and overly representative of medium and large campuses, it does provide the only available limited data regarding the scope and nature of on-campus health services.

Morbidity Data

Comprehensive data on college students are limited in many areas; although age-group is easily identified in most data sets, current

college enrollment is not always collected as part of standard demographic data.

college enrollment is not always collected as part of standard demographic data.

ACHA-National College Health Assessment

One source of data regarding the health of the college student population is the ACHA-National College Health Assessment Survey (ACHA-NCHA). This survey began in the spring of 2000. Since its inception, over 1 million students have completed the ACHA-NCHA and the ACHA-NCHA II (starting in 2008). While the students sampled on any given campus are selected in a randomized manner, the participating IHE do not represent a random sample and the response rate is fairly low. The ACHA-NCHA data throughout the rest of this chapter are from the ACHA-NCHA’s Undergraduate Students Reference Group Data Report Spring 2013. All NCHA surveys are available at http://www.achancha.org/.

NCHA 2013 Undergraduate Data Set

Survey includes 153 IHEs (127, 4-year and 26, 2-year institutions) that chose randomly selected students (N = 94,911).

Size of institution: 40 had more than 20,000 students; 42 had between 10,000 and 19,999; 39 had between 5,000 and 9,999; 16 had between 2,500 and 4,999; and 16 had less than 2,500.

Gender: The sample of students was 65% female.

Ethnicity: The ethnicity of the students was 67% White, 7% African American, 15% Hispanic, 12% Asian, 2% Native American/Alaskan Native/Native Hawaiian, 4% biracial, and 3% other.

Other Surveys of College Student Drug Use and Mental Health

Monitoring the Future Study (since 1975) (http://monitor-ingthefuture.org/)

Core Alcohol and Drug Survey (since 1989) (http://core.siu.edu/)

The College Alcohol Study (1993, 1997, 1999, and 2001) (http://archive.sph.harvard.edu/cas/)

The Cooperative Institutional Research Program (CIRP) Freshman Survey (http://www.heri.ucla.edu/cirpoverview.php)

Mental health data are available through the Healthy Minds Study (since 2007) (http://healthymindsnetwork.org/)

Care at SHSs is informed by key aspects of the college student population.

College student populations are generally young and healthy; 91% of students surveyed reported their health as good, very good, or excellent.4

College students are very mobile and often have several residences throughout the year, including in their hometown, on campus, and perhaps in a foreign country or near a summer job or internship.

The primary disease burden affecting students while in college is from mental health conditions and preventable accidents and injuries often associated with alcohol use.

Short-term goals are student academic and personal success. The longer-term goal is the primary prevention of the diseases of later adulthood, including obesity and tobacco-related illnesses.5

More young adults are entering college with chronic diseases. While some have medical conditions such as asthma, diabetes, and physical disabilities, the greatest increase has been in students with mental health disorders, learning disabilities, and pervasive developmental disabilities. Students with these chronic diseases need comprehensive services and case management to meet the goals not only of good health and functioning, but also optimal long-term academic, vocational, and personal success.

Many college students engage in behaviors that place them at increased health risk, including excessive alcohol use, prescription drug abuse, failure to engage in recommended physical activity, poor nutrition, failure to protect themselves against sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and high-risk recreational and vocational activities such as international travel.

Relationship difficulties and interpersonal violence are frequently reported.4

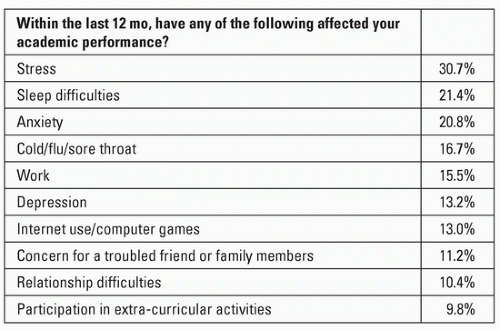

Mental health conditions and psychosocial stressors are frequent impediments to academic success. Of the top ten self-reported impediments to academic success only two are physical, while issues such as anxiety, sleep difficulties, and stress carry the greatest impact on student learning4 (Fig. 74.1).

In the academic year 2010, there were 21 million college students in the US. This is projected to rise to 21.9 million in 2015 and 23.5 million in 2020.1 Enrollment has increased 32% between 2001 and 2011 (15.9 to 21 million). Although an increasing proportion of young adults below age 24 are enrolling, the greatest increase has been in students above age 25. College populations have become more diverse, including enrolling more first-generation students as well as both students of color and international students. Data and extensive tables regarding higher education enrollment are available from the National Center for Education Statistics at http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest as well as the almanac issues of the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Trends

Gender: Female enrollment has risen from 29% in 1947, to 37.6% in 1961, 41.8% in 1971, 51.7% in 1981, 54.7% in 1991, 56.3% in 2001, and 56.8% in 2012. Between 2001 and 2011, female enrollment rose 33% and male enrollment by 30%. Currently, approximately 43% of college students are male and 57% female.

Age: Between 2001 and 2011, the number of 18- to 24-year-olds in the US rose from 28 million to 31.1 million (11%) while the percentage of this population enrolled in college increased from 36% to 42%. However, during this time period, the percentage increase has been even higher for students aged 25 and older (41% for those 25 and older and 35% for those under 25).

Enrollment status: Between 2001 and 2011, undergraduate enrollment and postbaccalaureate enrollment both rose 32% (from 13.7 million to 18.1 million for undergraduate and from 2.2 million to 2.9 million for postbaccalaureate).

Ethnicity: Between 1976 and 2011, the following changes have occurred among American college students:

Hispanic: Increased from 4% to 14%

Asian/Pacific Islanders: Increased from 2% to 6%

Black: Increased from 10% to 15%

Native American/Alaska Native: Increased from 0.7% to 0.9%

White: Decreased from 84% to 61%

International students: The US enrolled the highest number of international students in its history to colleges and universities during the 2012 to 2013 school year (N = 819,644). This number has increased for 7 consecutive years and has increased by 40% in past 10 years.6

Medical Care

Most SHSs, 93% on the ACHA-SHS Survey, provide some level of care for students with acute and chronic medical problems. Fewer than 6% of campuses on the ACHA-SHS Survey, however, reported having an overnight infirmary or 24-hour care as they can no longer justify the cost, risk, and resources associated with these services.7

Acute medical conditions such as minor infections (Epstein-Barr virus infections, genitourinary tract infections, upper respiratory tract infections, and acute gastroenteritis), musculoskeletal injuries, minor trauma, and skin problems are the most frequent conditions seen.

Reproductive issues are common, including the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of STIs, contraceptive management, routine gynecology, men’s health care, and unintended pregnancies.

Most SHSs have active immunization programs, and many offer pretravel counseling and vaccinations.

While only approximately 4% of college students surveyed report a chronic medical illness, many college undergraduate and older graduate students receive care at the SHS for these chronic medical conditions, including asthma, diabetes, seizure disorders, thyroid disorders, hypertension, eating disorders, and malignancies.4 Given the 10% or more estimate of chronic illnesses in this age-group, it is likely that college students are underreporting their chronic diseases and may also be underutilizing health care services for this purpose.

Integration of routine screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for depression, alcohol misuse, and tobacco use during all encounters, including acute care visits for minor conditions, has been a growing trend. These strategies should now be considered a standard of care for the college student population.8

Mental Health Care

Mental health symptoms, particularly depression and anxiety, are a frequently reported impediment to academic success, much more so than physical illnesses.9 Common diagnoses in this population include stress-related symptoms, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, suicidality, chronic fatigue, substance abuse, and other disorders affecting academic performance such as attention deficit disorder. Approximately, 20.1% of NCHA respondents reported being diagnosed or treated for a mental health condition by a professional in the preceding 12 months.4

Other reported symptoms on the NCHA include the following:

84.3% reported feeling overwhelmed with all they had to do.

46.5% reported feeling hopeless.

51.3% reported overwhelming anxiety.

31.8% reported feeling so depressed it was difficult to function.

8% reported seriously considering suicide.

1.6% reported attempted suicide.

Given the significant impact of mental health on student well-being and academic success, almost all IHEs offer some level of mental health services. Services may be available through a stand-alone counseling service integrated into a larger umbrella unit which provides medical and mental health care or both. As mental health disorders have increased in both severity and prevalence and campus threats of violence have become more common, college mental health, historically based in a developmental model which focused on academic support and developmental concerns, has undergone a significant transition. Common now is the availability of psychiatric consultation and the creation of campus teams (“threat” assessment or behavioral intervention) with procedures to share information and develop interventions such as mandated mental health assessment for when students display behaviors of concern and are felt to pose a risk to self or others.10

In data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, young adults enrolled in school are more likely than their peers to receive mental health counseling, while health insurance status was not found to have a similar effect.11 While the easy access provided by on-campus mental health services may play an important role in not on removing barriers to receiving care, significant treatment gaps remain. Evidence suggests that less than 25% of students with mental health diagnoses are currently receiving treatment.12 More concerning are estimates that only one-third of students with depression and approximately half of students who report suicidal ideation are in treatment.13 College students are less likely than their non-college-attending peers to receive alcohol and other drug treatment.12 Adequacy of treatment may also be limited, with estimates that less than one-quarter of students in treatment are adequately treated.13 Men, students of color (Black, Hispanic, and Asian), and international students are significantly less likely to report receiving mental health treatment than their female, White, and domestic student peers, respectively.11,13,14

These unmet mental health needs are a frequently cited concern of SHS providers and IHE staff. Most on-campus mental health services operate from a short-term model, referring students with complex or long-term needs to community providers. Lack of insurance coverage and a shortage of community providers are frequent barriers to students receiving care. To better meet the needs of students on campus, many SHSs are embracing novel approaches, including more closely integrating medical and mental health services.15 Behavioral health programs offer brief, solution-focused mental health counseling integrated into primary care to address high-risk behaviors such as alcohol or tobacco use, treat stress and sleep disturbances, or as a bridge to more comprehensive mental health care. Delivered within the medical setting, these services are often acceptable to underserved students, male students, international students, and students of color.16 SHSs are also enhancing support for students with chronic mental health conditions through the use of interdisciplinary teams for management of students with eating disorders and offering programs such as dialectical behavioral therapy.

Health Promotion, Wellness, Prevention

The campus environment presents a unique opportunity to use prevention strategies for optimal individual health and student academic success. Often referred to by the term “health promotion,” most campuses have specific programs which advance student well-being through individual education and wellness programming as well as using environmental strategies such as broad health campaigns and changes to campus health policy. These health promotion and wellness functions are typically part of the SHS—70% on campuses on the ACHA-SHS Survey—or also may be a part of a closely aligned unit such as Division of Student Affairs or Student

Life.7 These programs also conduct population-level assessments to determine areas of greatest need to focus their activities.

Life.7 These programs also conduct population-level assessments to determine areas of greatest need to focus their activities.

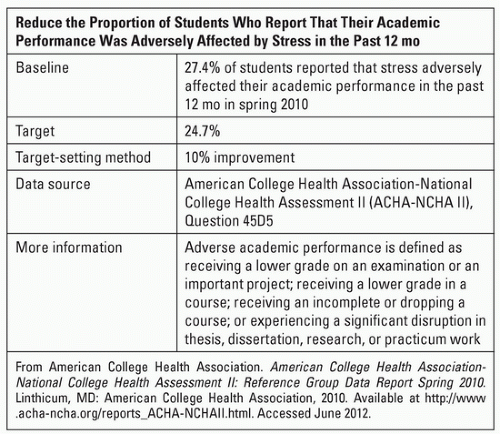

Healthy Campus 2020 provides a framework for improving the overall health status of a campus population and is utilized by many IHEs in evaluating campus health. Healthy Campus 2020 was developed by ACHA as a “sister” document to Healthy People 2020. Strategies suggested in Healthy Campus 2020 extend beyond traditional interventions of education, diagnosis, treatment, and health care within clinical setting and encourage collaborations between academic, student affairs, and administrative colleagues. Healthy Campus 2020 provides specific national health objectives for students and faculty/staff and utilizes an ecologic approach. This approach combines population-level and individual-level determinants of health and interventions as well as community-focused issues. Topic areas with Healthy Campus 2020 include impediments to academic success, health communications, injury and violence prevention, mental health, nutrition and weight, physical activity and fitness, STIs, family planning, immunizations, infectious disease, and substance abuse. IHEs can utilize Healthy Campus 2020 to set campus-specific goals and utilize measurable objectives to benchmark their performance nationally and internally17 (Fig. 74.2).

Public Health and Communicable Disease Control

The close living and working conditions of a college campus create a high-risk environment for communicable disease outbreaks. The academic calendar brings large populations to campus from throughout the nation and world in short periods of time. Well-described outbreaks have included the following:

Meningococcal disease—First year students residing on campus are at increased risk. Recent outbreaks have been associated with the Group B serotype. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that AYA aged 16-23 years may be vaccinated, preferably at 16 through 18 years old, with a serogroup B meningococcal vaccine to provide short-term protection against most strains of serogroup B meningococcal disease.

Norovirus: This can be particularly difficult to contain and has led to outbreaks in the hundreds and in some cases over 1,000 cases in a short period of time on multiple campuses.

Vaccine preventable disease outbreaks including mumps, measles, and varicella have been well described. Mumps outbreaks have been common on campuses over the past 10 years, with most cases in fully vaccinated individuals.

Pertussis: A potentially significant issue in young adults

Bacterial conjunctivitis

Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Outbreaks have been particularly associated with athletic teams and recreational sports facilities.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Recent outbreaks have been described on several campuses.

Influenza and other upper respiratory viruses: These cause significant morbidity among college students, including increasing health care utilization and impacting academic performance.19 The 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic uniquely impacted campuses. Preferentially impacting young adult populations, SHSs across the nation experienced a profound health care surge that strained campus resources but also led to the creation of a stronger public health infrastructure on many campuses.20

Detection and control of communicable diseases, therefore, is one of the most critical roles played by SHSs and a public health framework in which the SHS is a kind of local public health agency is utilized on many campuses. Roles of the SHS in communicable disease control include primary prevention through immunization and health education campaigns, active surveillance for diseases, and detection of individual cases or suspect cases. For example, many SHSs are part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sentinel influenza surveillance network. During an active outbreak or when managing individual cases of communicable diseases, the SHS may assist or have primary responsibility along with local public health authorities for case management and contact tracing. SHSs advise or coordinate public information campaigns for the campus community. Public health approaches are also now being utilized to address a variety of other chronic diseases and health risks among student populations, including high-risk alcohol use, mental health, interpersonal violence, and obesity.

Similar to other AYA populations, college students have a range of risk factors that must be considered when delivering health care. Screening and appropriate intervention can reduce short-and long-term health risks. Overall in the US, the highest risk factors are in emerging young adults 18 to 25 years old (www.usc.edu/thenewadolescents).

Alcohol

Alcohol remains one of the most serious public health problems facing college students in the US. College students are more likely than their noncollege peers to engage in heavy episodic drinking, also known as binge drinking, defined as 4 or more drinks in a row for women and 5 or more drinks in a row for men. While college students are not more likely to experience alcohol dependence than their noncollege peers, their alcohol use places them at risk for unintentional injury, victimization, and other health and personal consequences such as academic and legal difficulties.21,22

Surveys of college students consistently demonstrate high levels of alcohol use among undergraduates and its attendant consequences.

Over 60% of students report any use within the past 30 days.4

Approximately 40% report binge drinking within the past 2 weeks.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree