Developing successful programs in a community cancer center involves collaborative efforts between employed and private practice physicians, hospital and cancer center administrations, support personnel, and significant resources, coupled with a vision that will lead to improved patient care and outcomes. Collaboration through a strong state cancer control program is another important component for a successful community cancer center. Delaware has one of the best state cancer control programs in the United States. In 2001, the Delaware Cancer Consortium was formed, which, in 2002, launched its first statewide program to screen all Delawareans older than 50 years with colonoscopy.

- •

Successful community centers should have (1) program development with a core comprising high-quality well-trained professionals, (2) resources, (3) collaboration with institutions of higher learning, and (4) collaboration with community organizations.

- •

The National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program involves 7 pillars of care and research, including disparities, clinical trials, patient advocacy, biospecimen collection and preparation, and survivorship programs.

- •

Establishing genetic counseling and gene-testing programs is important to lower cancer incidence and mortality in any state. This effort needs to involve primary care physicians who refer patients to genetic counselors for evaluation and possible gene testing.

- •

The key to a successful disease site multidisciplinary center is a care coordinator or nurse navigator to coordinate scheduling and guide the patient through the complex maze of cancer care and follow-up. The nurse navigator is the key communicator to the patients and their families.

- •

The Center for Translational Cancer Research (CTCR) is a formal alliance between the University of Delaware, the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, the Nemours Research Foundation/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, and the Delaware Biotechnology Institute at the University of Delaware. The CTCR has created a center without walls to support clinical and basic science efforts within the state.

- 1.

Program development must have access to a core of high-quality well-trained professionals.

- 2.

Resources must be available.

- 3.

Collaboration with institutions of higher learning is critical.

- 4.

Collaboration with community cancer organizations is critical.

Equipping a community cancer center to the level of an academic center requires the collaboration of several institutions. The Helen F. Graham Cancer Center (HFGCC) at Christiana Care is fortunate to have strong collaborative efforts and research agreements with the University of Delaware and the Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University. The center has also been fortunate to have an outstanding relationship with community cancer organizations, such as the American Cancer Society, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, the Delaware Breast Cancer Coalition, and the Wellness Community. Collaboration through a strong state cancer control program is another important component for a successful community cancer center. Delaware has one of the best state cancer control programs in the United States. In 2001 the Delaware Cancer Consortium was formed, which, in 2002, launched its first statewide program to screen all Delawareans older than 50 years with colonoscopy. These results are further discussed in this article.

In May 2007, the HFGCC became 1 of the 16 members of the original National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program (NCCCP) to allow access to the cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (caBIG) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and The Cancer Genome Atlas project; this is also discussed in this article.

Participation in the NCCCP

The NCCCP involves 7 pillars of care and research:

- 1.

Disparities

- 2.

Clinical trials, especially increasing minority accrual to clinical trials

- 3.

Patient advocacy

- 4.

Biospecimen collection and preparation

- 5.

Survivorship programs

- 6.

Quality of care, including the multidisciplinary approach to cancer care

- 7.

Information technology with implementation of electronic health record.

The NCCCP involves a network of 16 original institutions, which increased to a total of 30 in the spring of 2010. Disparities overtake all of the 7 pillars of the NCCCP. This program was the concept of John Niederhuber, MD, former Director of the NCI. The program came into existence because Dr Niederhuber realized that 85% of patients with cancer in the United States are diagnosed at community hospitals with the remaining 15% diagnosed at the NCI-designated cancer centers, which are mainly located in urban areas. It is also known that many patients are not treated at the NCI-designated cancer centers because of economic reasons, distance from home, or personal reasons. The mission of the NCCCP is to enhance cancer care at community hospitals and also to create a platform to support basic, clinical, and population-based research. As of now, the 30 NCCCP sites located in 22 states are developing and evaluating programs to enhance community-based cancer care and create a community cancer center network to support research. This network also supports research in collaboration with the NCI-designated Cancer Centers Program, The Cancer Genome Atlas project, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. In the area of enhanced community-based cancer care, the institutions in this network are reducing disparities in cancer health care across the cancer continuum, at the same time improving quality of cancer care and expanding survivorship and palliative care programs. In the area of cancer research initiatives, the NCCCP institutions support the investigation of new drugs through clinical trials, increasing the quality of biospecimen collection procedures for research through a standardized base approach and expanding information technology capabilities through electronic medical records and, as mentioned earlier, the NCI’s caBIG. Examples of some of these projects are as follows:

- 1.

To meet the NCI’s need for standardized data, the NCCCP hospitals have united in their approach to collecting race and ethnicity data. The NCCCP sites are standardizing race and ethnicity data collection using the US Office of Management and Budget guidelines and categories.

- 2.

The NCCCP sites, through their staff, have embraced the need for improved cultural awareness of specific populations to make progress toward reducing health care disparities. The sites have worked with individuals in the field and patient advocates to develop webinars exploring the health histories and beliefs of African Americans and Native Americans.

- 3.

The NCCCP sites, along with the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer, are testing the Rapid Quality Reporting System of the Commission. This system provides real-time surveillance and feedback to centers on the status of patients whose cancer care falls within the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.

- 4.

The NCCCP sites are working with their community-based private practice oncologists in participating in the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. This initiative involves monitoring physician adherence to evidence-based guidelines for treatment and surveillance.

These are but a few examples of the projects that the NCCCP is involved in. The projects have been successful because of the participation of private practice oncologists of all cancer disciplines. The NCCCP is a model network wherein institutions share best practices and are involved in continued communication across all 7 pillars to improve patient care and research.

State cancer control program

The state of Delaware reports approximately 4600 new cancer cases on an annual basis. In 2010 the overall population of Delaware was 876,653. The most common cancers in the state are those that are reflected nationally: lung, breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers. A substantial number of melanomas are diagnosed each year because of the existence of beaches in the southern part of the state and subsequent unprotected sun exposure. In the past, Delaware was ranked number 1 in the United States for both cancer incidence and mortality. In view of the success of many screening, treatment, and genetic counseling/gene-testing programs, Delaware’s mortality rate is dropping twice as fast as the national rate. A major impact has been the Clean Indoor Air Act passed in November 2002, which, along with the statewide colorectal screening program, constitutes the 2 main reasons for the improvement of cancer statistics in the state of Delaware. The Delaware Cancer Treatment Program has been contributing to this success. Funds from the tobacco settlement have been used to establish the Delaware Cancer Treatment Program. An uninsured family of 4 in the state of Delaware earning up to $120,000 per year can receive 2 years of cancer treatment. The individual simply has to be a resident of the state. In addition, in 2007 an education program for the human papillomavirus vaccine was started, which continues to this day and which in the future will certainly have a dramatic impact on cervical cancer incidence across the country.

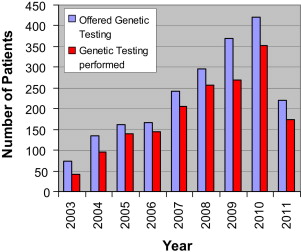

Before 2002, there was not a single full-time adult genetic counselor in the state. At present, there are 4 full-time adult genetic counselors at the HFGCC who serve the state of Delaware. A high-risk family cancer registry named after the former governor of the state, Ruth Ann Minner, has been established. This registry has more than 100,000 individuals and 2000 families. The bar graph in Fig. 1 demonstrates the number of patients offered genetic testing and the actual number of patients who underwent testing from 2002 to 2011; the dramatic increase in both is self-explanatory. This increase has taken a tremendous educational effort on the part of the genetic counselors with both physicians and the public.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree