While most physicians know that payment for their services must usually be coded and billed for monetary reimbursement to happen, their traditional medical education and training has not provided them much information on how this is actually accomplished. And, while it is true that most physician practice groups have employed personnel trained in medical professional coding and billing, those personnel are completely dependent on the quality of physician documentation in the medical record. The rules for coders usually dictate the specific requirements that must be in the medical record to enable them to code appropriately for any given service. Therefore, physicians who are knowledgeable about the documentation requirements will likely see better reimbursement for their services than those who are not by making it easier for their coders to apply the correct codes. The purpose of this chapter is to provide the information and guidance for trauma surgeons to optimize their professional reimbursement as a result of a better understanding of documentation, coding, and billing rules.

Prior to the 20th century, physicians in the United States were paid for their services directly by the patient. Because of new developments and discoveries, the ability to provide lifesaving remedies became increasingly available, but was accompanied by increasing costs. The concept of using an insurance model (designed to pay for catastrophic events that were unlikely to occur) first evolved in the private sector in the late 1920s.1 Initially limited, private health care insurance received a significant boost during World War II, when a restrictive wage freeze forced industries to compete with other options for the scarce able-bodied men who were present stateside. Employer-based health care insurance ultimately became the norm in American society with extremely few exceptions.

Upon retirement, however, such employer-based health care insurance was no longer available to retirees, who were now forced to pay for their increasingly expensive health care needs out of their fixed social security income. Throughout the 20th century, there was a progressive movement to socialize American medicine and provide health care benefits for all citizens. A major milestone in this effort was the implementation of Medicare in 1965, which provided health care benefits to social security beneficiaries. Given the huge population of individuals covered by Medicare, it became an essential monopoly governing the provision of health care for previously employed individuals over the age of 65.

Initially, patients submitted health care claims to Medicare and then received payments from Medicare to turn over to their physicians. Because many patients did not transfer that claim payment to their physicians, Medicare began to offer physicians the option of accepting “assignment.” This meant that physicians would accept payment directly from Medicare instead of directly from the patient. With this benefit came the requirement that the physician would agree to accept Medicare’s allowed amount as payment in full. Ultimately, private insurers followed suit, with actual payments by patients becoming minimized to the level of deductibles and copays, which were designed to prevent excessive or unnecessary use of health care resources by patients. Current-day health savings accounts seek to provide the same disincentives to patients.

The modern era of payments to physicians began in the 1980s, when assessments of the financial health of Medicare indicated that the program was on course to bankrupt the social security system. As a consequence, cost-cutting measures were instituted over a number of years, primarily aimed at lessening payments to physicians and hospitals. On the physician side, the concept of a Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) was developed as a means to quantify physician services on a relatively objective basis.2 The American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), an annually produced catalog of services and procedures performed by physicians, served as the structural basis for the RBRVS. For each CPT code, an assessment has been made of the amount of physician work, practice expense, and malpractice costs associated with that service or procedure. These assessments were summed for each CPT code, and the resulting totals were ranked in a standardized scale to produce relative value units.

Relative value units serve as the fundamental currency for physician services. The entire concept and structure for physician RVUs under Medicare is defined in the United States Code of Federal Regulations.3 Every procedure or service performed by physicians is assigned a specific number of RVUs, which is an aggregate of the amount of physician work, practice expense, and malpractice expense as noted above. While the valuation of each of these components varies slightly for each CPT code, physician work valuation comprises about 50% of the total RVU payment, with practice expense averaging roughly 40% and malpractice expense averaging about 10%.

Physician work, in turn, is determined based upon assessments of the time spent, the technical skill and/or physical effort required, the amount of mental effort and judgment required, and the stress arising from any potential risk to the patient from performing the procedure or service. These assessments are developed by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) comprised of representatives from physician specialty societies and the American Medical Association. The RVU valuations are recommended to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which then produces a quarterly update of RVU valuations on its Web site.4

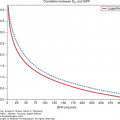

Physician reimbursement is directly tied to RVUs through the Conversion Factor, which specifies the number of dollars paid for each RVU. Unfortunately for physicians, the conversion factor has not kept pace with inflation. For example, the conversion factor was $34.73/RVU in 1999, while the conversion factor was $35.75/RVU in 2015. If the conversion factor had kept pace with inflation, it would now be $48.93/RVU. While the difference of $13.18 may seem trivial, a general surgeon with an average production of 7000 RVUs annually now only earns $250,250 instead of the $342,510 he or she would have earned if the conversion factor had kept pace with inflation, representing an annual loss of $92,260.

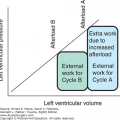

Payments to physicians are made for services and procedures. Services represent patient interactions such as clinic visits, emergency department visits, consultations, inpatient admissions, daily rounds, critical care services, and others. While there may be some procedures bundled into these services (such as is the case with critical care services), the majority of this work on the physician’s part involves evaluation and management (E&M) of the patient’s condition, which are primarily cognitive in nature. As opposed to E&M services, procedures include surgical operations, bedside procedures, anesthesia services, radiological interpretations and procedures, and performance or supervision of laboratory procedures. Also, in comparison to cognitive-only E&M services, procedures involve actual physical work by the physician in addition to cognition.

Most patients do not pay their health care bills directly out of their checking account or credit card, as they do with other purchases. Instead, health care services are usually paid by third parties, usually an insurance company or a government entity such as Medicare or Medicaid. These entities seek to ensure that they are paying for actual and appropriate services. Therefore, they demand to know what was done for the patient and why it was done before they will process a payment to the physician.

The “why” takes the form of one or more coded diagnoses, currently using the diagnoses enumerated by the World Health Organization in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Since the early 1980s, CMS and other third parties required the use of a clinical modification (CM) of version 9, ICD-9-CM, for this purpose. Starting in October, 2015, the system converted to the use of ICD-10-CM for coding diagnostic conditions.

The “what” is contained in one or more CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) codes, which are revised and produced annually by the American Medical Association. CPT provides a system that lists and codes the majority of procedures and services provided by physicians. CMS has established the CPT system as level I of the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). Level II HCPCS codes apply to nonphysician services that are billed to CMS, such as ambulance services, prosthetic devices, and rehabilitative services. In addition to identifying the procedure or service performed, the CPT code is the entity to which RVUs are assigned.

It is not uncommon that multiple procedures are performed during the same operation and, in many cases, they can all be reimbursed. In an effort to counteract procedural “unbundling,” however, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA)—–CMS’s previous name—–established the Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) in the early 1980s. The CCI defines those procedures that cannot be billed simultaneously.5 For example, the higher paying splenorrhaphy (CPT 38115, 21.88 work RVUs) cannot be reported at the same time as a splenectomy (CPT 38100, 19.55 work RVUs) as reporting both being performed during the same operation will result in payment for the lower paying splenectomy alone. While seemingly reasonable, there have been several instances where the prohibition of simultaneous billing makes little sense.6 In such cases, appeals can be made with proper documentation and, often, with modifiers.

Modifiers indicate that there is a change in the fundamental assumption about the service or procedure represented by the CPT code. To ensure appropriate reimbursement, CPT codes may need to be reported with one or more modifiers. As will become apparent, modifiers play an important role for trauma surgeons because of the multiple conditions being managed during surgical global periods. For example, most procedure codes are considered to have some degree of E&M services incorporated into the payment for the code. Therefore, payment for any additional E&M services that are unrelated to the procedure must be justified by the addition of a modifier.

Appropriate and thorough documentation in the medical record is necessary for effective coding and billing. While most physician groups have professional coding and billing personnel helping in the process, their task is completely dependent upon good physician documentation as noted previously. The coders simply cannot generate any ICD-10 or CPT codes unless the basis for those code assignments exists in the physician documentation. The documentation must provide information regarding the condition(s) or disease(s) being treated and the procedures or services used in the treatments. Coders translate the documentation into ICD-10 codes for the diagnosis and into CPT codes for the procedures or services. In addition, the procedures or services must be appropriate for the conditions being treated. For example, if a patient admitted with a sacral fracture (ICD-9 code 805.6/ICD-10 code S32.1) requires insertion of a central venous catheter (CPT code 36556 for nontunneled catheter in an individual >5 years old), there will need to be a separate diagnostic code to justify reimbursement for the central venous catheter as a sacral fracture by itself will not provide that justification. Thus, conditions such as hypovolemia (ICD-9 code 276.52/ICD-10 code E86) or traumatic shock (ICD-9 code 958.4/ICD-10 T79.4) should be identified as the reason for the central venous catheter. Many of the coding software programs used by billing personnel have cross-coding applications that alert coders when a procedure may not be appropriate for a specific diagnosis, or vice versa. Fortunately or unfortunately, there are no universal standards for these code pairs. Therefore, there have been situations in which the coding office is telling the physician they’ve identified an inappropriate diagnosis for a particular procedure and yet the physician knows that his or her diagnosis and procedure code pairing is clinically appropriate. In such circumstances, the physician will need to provide the appropriate clinical guideline, policy, or medical literature to educate the coding staff and provide effective clinical feedback for cross-coding.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree